Philosophy Placement Data and Analysis: An Update (guest post by Carolyn Dicey Jennings)

The following is a guest post* by Carolyn Dicey Jennings (UC Merced), who has led a team of academics in producing and organizing a trove of data related to the graduation and placement records of English-language philosophy Ph.D. programs (previously). The team just published an update to its 2015 report, “Academic Placement Data and Analysis” (APDA). Among other things, the update contains the graduation and placement data for specific programs, some of which I’ve included below the post. Thanks to Professor Jennings and the rest of the team—Patrice Cobb, Chelsea Gordon, Bryan Kerster, Angelo Kyrilov, Evette Montes, Sam Spevack, David W. Vinson, and Justin Vlasits—for their work on this project.

An Update to Academic Placement Data and Analysis

by Carolyn Dicey Jennings

I am happy to report that the Academic Placement Data and Analysis (APDA) project has been able to release an update of its 2015 report, which includes program-specific placement rates. We decided not to include those in the original 2015 report because of errors we found just before its release. Those errors were in fact for records entered by placement officers and department chairs over the summer (e.g. missed placements), so we decided to spend the next six months or so checking the placement records in our database against other available sources, such as the PhilJobs Appointments page and program-specific placement pages. Having integrated that data, while also checking for duplicates and other errors, we feel confident enough in the data we have to release program-specific placements. This is a first for our discipline, and I am very grateful to all who have helped make it happen, including the American Philosophical Association (APA), all the APDA project personnel, and numerous people in philosophy who have helped the project in different ways (and me, when I needed it).

A first note: this does not mean that our database is error free. Only a week ago, long after removing duplicates in the database, Angelo Kyrilov noted that I was in the database twice—once for Boston College and once for Boston University. This was a coding error that was not caught in our system of checking for duplicates because one entry had my last name as “Jennings” and the other had my last name as “Dicey Jennings.” While we did check for misspellings of names, these were far enough apart in the alphabet to miss the duplication. I think it is a sign of the scientific nature of our project that the project head (me!) could have an incorrect entry. Yet, it is also a reminder that errors are inevitable in a project of this nature. We have made significant efforts to reduce and remove them, but when we add the option of individual editing in May we hope that still more will be noticed and removed.

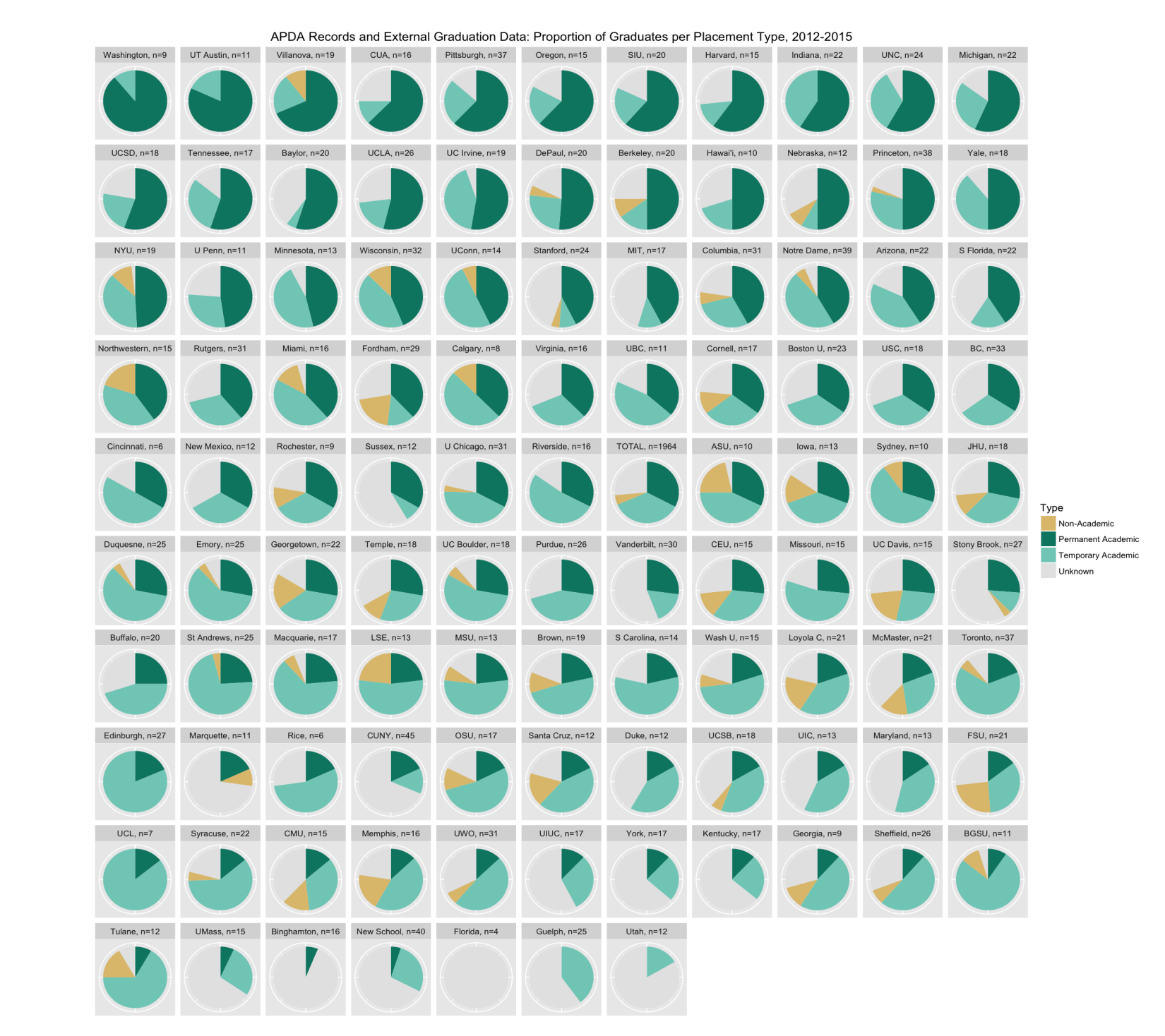

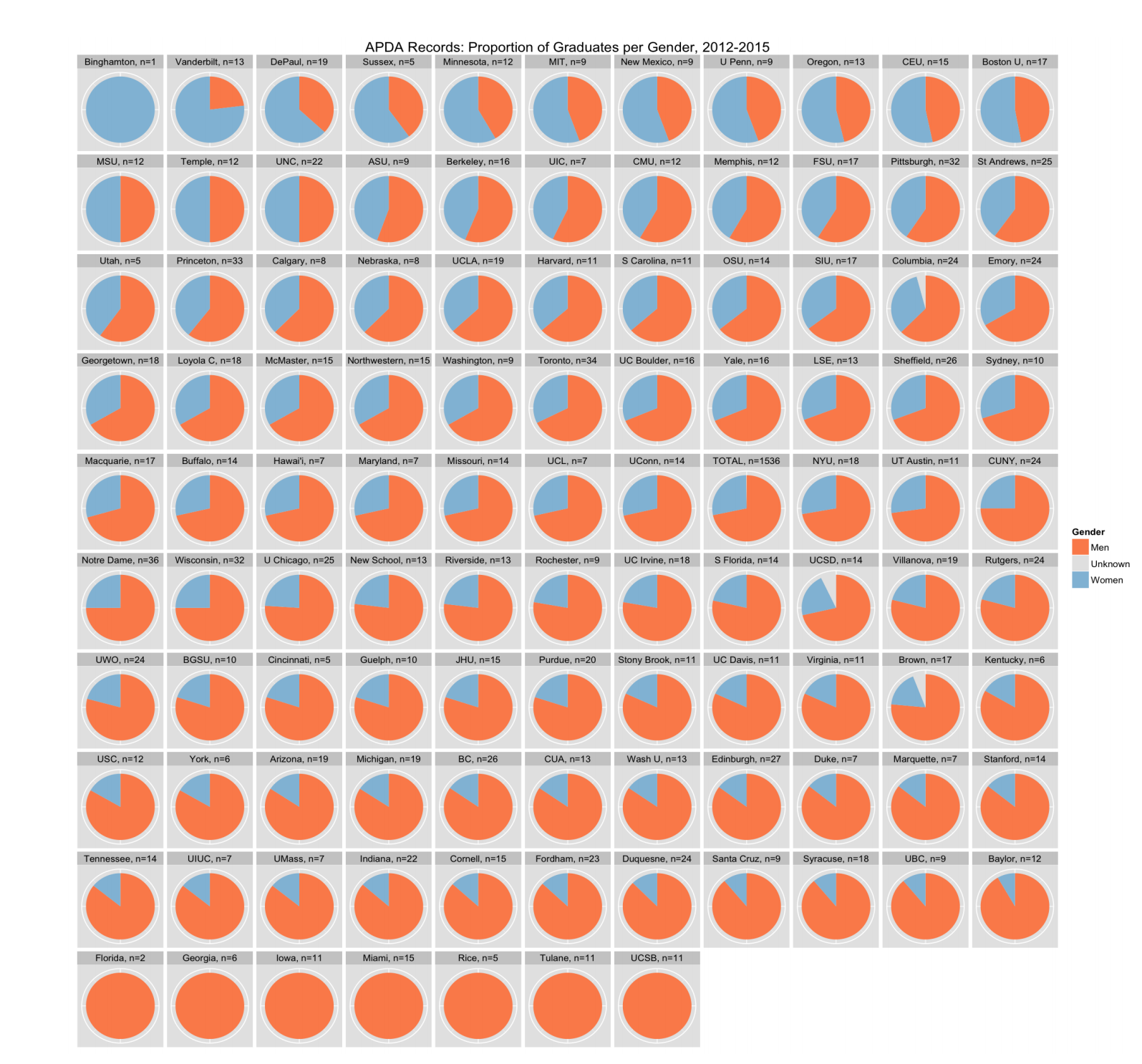

So what did we find? One notable difference between this report and the one released in August is that we did not find a significant effect of gender on placement this time. There were some differences in how we made our comparisons—in the last report we grouped all but permanent in one category, comparing this to permanent placements. In this report we separated out temporary academic positions, nonacademic positions, and no reported positions (we have a small number of the latter two categories—251 total nonacademic positions and 204 graduates with no reported positions). We did this because we hope to expand our project to take better account of nonacademic positions. If we had used the previous model we would likely have found significance. In our database, 54% of the women have permanent academic positions, whereas only 49% of the men have permanent academic positions, and this difference is significant using a chi-squared test (p<.01). Yet, I was surprised that a number of programs (7, or around 7%) had no reported women graduates in the time period we looked at: 2012-2015. It is important to remember that disparity in philosophy is still high. (See this recent draft by Eric Schwitzgebel and myself for an in-depth accounting of that disparity.)

When reading our tables and graphs, keep in mind that 2015 is less-well represented in terms of number of graduates in our database: the 2015 graduates make up only 15% of the total graduates between 2012 and 2015 (the other three years each make up around the same proportion—28%). Since we did not add a time dimension to our analyses this year (but plan to do this in the future, as with the 2015 report), and since graduates of 2012 have had more time to secure permanent academic positions, those programs with fewer graduates from 2012 and more graduates from 2015 will likely appear to be worse off on placement relative to their peers than they actually are. (For this reason, I ordered the graduation year graphs by proportion of graduates from 2012.)

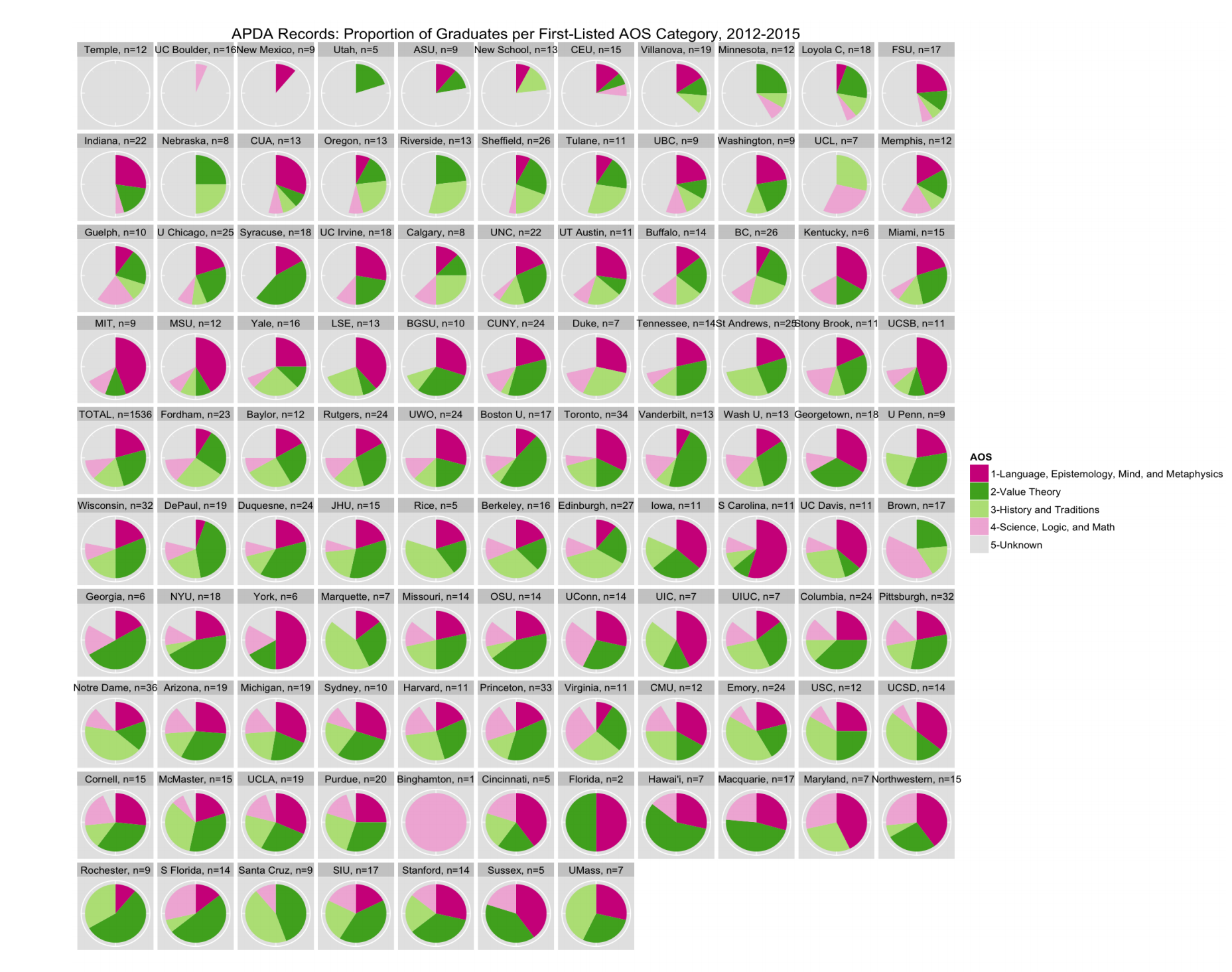

Also notable is that Value Theory remains the most popular of our first-listed area of specialization categories for this time period (2012-2015), with Language, Epistemology, Metaphysics, and Mind in second place, History and Traditions in third, and Science, Logic, and Math as the least populated of the categories. (This is excluding the “Unknown” category, which in fact beats Value Theory.) Nearly every program had some graduates with first-listed AOS in this category, with only 12 with no such graduates (excluding two programs for which we have only unknown AOS). Yet, Science, Logic, and Math was the category closest to significance, with more likelihood of those in our database with this AOS being reported as having a placement than not having a placement (in comparison with LEMM). (Value Theory and History and Traditions each had lower likelihoods for the academic positions and higher likelihoods for the nonacademic positions, but these values were not significant.)

Finally, we are still looking for the best way of capturing graduation data. Our current method is to take the mean for three external sources and then compare that to the numbers of graduates in our own database, taking the higher of these numbers. All three sources are good ones: the APA Guide to Graduate Programs, PhilJobs Appointments, and the Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED). Yet, there were lots of inconsistencies in the data. For example, in the same year a single program might have reported twice or three times the graduates in one source as in another (comparing PhilJobs and APA, since the data for both of these sources come from the departments themselves). This fact makes the search for reliable information about graduation numbers particularly tricky. If we were to use only SED data we might avoid some problems, but potentially fall prey to others, such as the fact that SED groups graduates by “field of doctorate” rather than department (and so might have higher or lower numbers for philosophy departments than they should, depending on how graduates see themselves). I am open to suggestions on this front. Needless to say, placement rates are sensitive to graduation numbers, so this is an important part of the project.

So what is the overall placement rate? Including graduates from all four years for 108 doctoral programs, and using external graduation data, 32% of graduates from 2012-2015 have by now found permanent academic positions and 68% have found academic positions of some kind. My supposition is that a large chunk of the remaining 32% are now in nonacademic positions. Yet our database only has record of a small proportion of these. For this reason, I am starting to think of the project somewhat differently, and will aim to do a better job collecting non-academic placements in 2016 by enabling individual reporting and editing of placement records. (I am supposing that placement officers and department chairs know less about these graduates.) We will begin thinking of how to categorize nonacademic positions so that we can, in future, have fewer reported unknowns and a better understanding of this large proportion of graduates.

Exciting developments are to come for APDA: we are going to send out a qualitative survey to all graduates in our database in May, reporting results in June. We are also going to add applications to the website that will allow users to interact more directly with the data, along with other website upgrades. If you have any feedback for the project, please let me know! We have turned off editing for now as we prepare for individual editing, but if you find any errors feel free to email me directly, preferably at the project email account.

See the rest of the data in the official APDA update.

Thanks so much for doing this (and thanks to your collaborators).

You say, “In our database, 54% of the women have permanent academic positions, whereas only 49% of the men have permanent academic positions.”

The data you give in the paper has permanent jobs for 457 out of 1168 men, which is 39%, and 228/466 women, which is 48%.

You don’t show the data broken down by gender *and* specialty together (so we could see how, e.g., LEMM men are doing compared to LEMM females). Will you be releasing that data?

Hi gopher–the first statement covers the entire database of 4k plus people, whereas the latter statement is for 2012-2015 graduates only (under 2k). I should probably have looked at the latter when checking for significance in this post, since that is the better comparison with the analysis in the paper. My guess is that both would be significant if we grouped as we did for the 2015 report. On allowing for comparison between multiple data categories: yes, we will do that in the future. On AOS and gender: check out the paper that I wrote with Eric, which has this information (with data from 12/15): http://www.faculty.ucr.edu/~eschwitz/SchwitzPapers/WomenInPhil-160315b.pdf

Right, I see the relevant part of your paper with Eric.

I was wondering, though, about how gender and AOS are related in the *placement* data. For example, women have a better placement rate than men — is this because they are more likely to be in value theory and value theory has a better placement rate? That sort of question.

Another Gopher,

You had to be another gopher? There are plenty of rodents. If you’re partial to Geomyoidea, couldn’t you be a kangaroo rat?

Good questions–women are more likely to have a first-listed AOS in the Value Theory category, but that category actually had a slightly lower likelihood of having a recorded placement versus no recorded placement (not significant and not using external graduation numbers). We prioritized getting this report out before April 15th and, as last time, had the least time to work on the analysis side. Hopefully in the coming months as we think through these issues more we can come up with interesting analyses to run on the data.

April 15th. Gosh. Well, Hopefully this can help some folks to make better informed decisions.

Just casually, I’m noticing that there are major differences between schools that are grouped together in Leiter’s recent rankings. Group 4, for example. Grad applicants, I beg you, don’t make the mistake I did and prioritize prestige over actual results.

How were so-called ‘Continental” dissertations classified? Is “Foucault on Knowledge” classified as a LEMMing diss, tradition diss, or unknown diss?

Off hand, I would probably group this as having a focus on Foucault, and thus Continental/History and Traditions, rather than having a focus on Epistemology, and thus LEMM. (Similarly for “Aristotle on Ethics.”) All AOS entries and categorizations were checked by both myself and Justin Vlasits (a graduate student in philosophy at Berkeley), but graduate dissertations were assigned AOS terms by myself and Evette Montes (who was more likely to select “unknown” if she couldn’t find this information on a c.v.).

Thanks. And thanks for putting this together.

Carolyn,

This is an absolutely fantastic service, and I am really grateful to you and your team for doing all this.

Anyway, I just wanted to briefly follow up on the comment from gopher. Judging from the numbers in the report, 39% of men got permanent positions, while 48% of women got permanent positions. This difference is highly statistically significant, chi-squared (1, N= 1634)= 11.485, p= 0.0007.

The actual report uses a more complex analysis that breaks down the people who did not get permanent positions into a number of different categories (none, non-academic, etc.). I don’t mean to criticize that analysis, but it would be a shame to lose sight of the straightforward fact that these data show that men are significantly less likely to get permanent positions than women are.

Thanks for this–just a follow up: these data do not include external graduation numbers, and the external graduation numbers I have do not include gender, and this information may well have an impact on the analysis. In other words, it may not be that men are less likely to get permanent positions but that men are more likely to get temporary academic positions and women are more likely to be in the unknown placement category. This conversation reminds me that SED has gender data, so we might be able to look into this after all. (But not today!)

Carolyn,

Thanks so much for this response — and thanks once again for everything you’ve done to create this fantastic report!

Carolyn,

Thanks to you and your collaborators for your hard work and the update.

Your initial 2015 report states, “In terms of differences, the odds of having a permanent (versus temporary) academic placement are 85% greater

for females as compared to males.” (p. 11)

However your update does not compare the odds of permanent (versus temporary) placement by gender. It only reports “Permanent academic placement relative to no placement” (pp. 8-9), “Temporary academic placement relative to no placement” (p. 9), “nonacademic placement relative to no placement” (p. 9), and “Both temporary academic placement and nonacademic placement relative to no placement” (p. 9)

Can you analyze and report the statistics/odds for the permanent (versus temporary) placement intersect by gender, as in the first report? This is a highly relevant intercept that came out highly significant in the original report.

p. 7 of the the update reports 225/446 women placed in permanent academic positions (48%) compared to 457/1168 (39%) for men. On p. 12 of the original 2015 report 138/257 (53%) of women placed compared to 269/681 (39%) of men. These figures are similar. It is hard to believe that an 85% advantage would retreat to a statistical null result after a one year update. The statistical probability of a retreat to null result is vanishingly small given the p-value (p<.0001) in the original report (a 1 in 10,000 chance).

Just want to say thanks to you and everyone who’s worked on the project. And I am looking forward to future data on non-academic job placement!

Thanks for the update, it’s very interesting, as per usual.

I’m pretty sure the only reason you didn’t find a significant effect of gender this year is that, as another gopher already noted, you didn’t perform the same analysis as in your last report, i. e. you didn’t compare the odds of reporting a permanent academic position vs a temporary academic placement. I have little doubt that, if you run that regression instead, you will find that gender has a significant effect. I also suspect that the effects of AOS will become significant and that some of them will be reversed.

Also, I seem to remember that you were using a multilevel regression model before, which doesn’t seem to be the case this year. I’m inclined to think a multilevel regression model is more appropriate here, but I don’t think that is what explain the non-significance of gender. You also used to control for the year of graduation, which strikes me as a rather important factor to control for.

I hope you will release the data at some point so that everyone can play with them and run their own analyses.

Hi Philippe–You and anyone else can use the data that has been made public here: http://faculty.ucr.edu/~eschwitz/SchwitzAbs/WomenInPhil.htm . This is from a pull I did in December 2015, not using a SQL Query but an Excel match function on the tables, which is more likely to lead to errors of various kinds. We will have to rewrite our SQL Query to better represent the different types of placements. (It currently implicitly prioritizes permanent over temporary and academic over nonacademic, such that if someone first got a permanent academic job but now has a nonacademic job we listed them as permanent. We will change that.) We will put up a public csv file with the website upgrades (as well as the reports), but that is not our top priority right now. I suspect we will complete those website upgrades in May or June of this year.

It is Appendix 2. Coding: 1=men, 2-women; 1=LEMM, 2=Value, 3=Hist, 4=Sci, 5=Unknown; >0=Placement (for both Perm and Temp).

It should not be your audience’s responsibility to carry out relevant analyses. Research ethics require researchers to present all relevant statistical analyses, not present data analysis selectively. This is to ensure that data are not misleadingly represented to the public. Your post states, “One notable difference between this report and the one released in August is that we did not find a significant effect of gender on placement this time.” Several commenters have noted this does not appear to be true, and it should not be asserted given that some relevant analyses from the 2015 report were not performed in the update. In order to justifiably assert whether a significant effect of gender was or was not found, one must perform and present statistical analyses of all relevant intercepts.

“Research ethics require researchers to present all relevant statistical analyses, not present data analysis selectively.”

I can’t think of a way this statement could be interpreted such that it is even remotely plausible.

Non-selectivity/completeness in statistical reporting is a widely recognized part of research ethics.

“Like any other field, there are ethics in statistics that need to be followed by a researcher so that only the truth is reported and there is no misrepresentation of the data…It is relatively simple to manipulate and hide data, projecting only what one desires and not what the numbers actually speak, thus giving birth to the famous phrase “Lies, damned lies and statistics”…Ethics in statistics are very important during data representation as well. Numbers don’t lie but their interpretation and representation can be misleading. For example, after a broad survey of many customers, a company might decide to publish and make available only the numbers and figures that reflect well on the company and either totally neglect or not give due importance to other figures.”

https://explorable.com/ethics-in-statistics

That’s not what you were talking about.

This quote is about completeness in *reporting results*, not about carrying out “all relevant statistical analyses” … in what sense “relevant”? And why would that be her responsibility? Of course researchers are selective about what analyses to perform, according to what they judge is best, what they think is interesting or exciting, etc.

And I still find what you quote there problematic —in some sense, “manipulating data” is just what researchers do.

It is relevant in the sense that the study found an 85% gender advantage last time on the intercept, but Carolyn did not test it this time before publicly claiming a null result for gender advantage.

“Your post states, `One notable difference between this report and the one released in August is that we did not find a significant effect of gender on placement this time.’ Several commenters have noted this does not appear to be true”

I missed the commenters who noted that we did in fact find a significant effect of gender on placement this time. I did notice that some commenters agree with what I say in my post–that we would have likely found significance if we had run different analyses, collapsing across distinctions. I, like babygirl, disagree with your phrasing of what is required of researchers, but perhaps you could rephrase it? In any case, we presented all of the analyses that we ran.

Hi Carolyn,

Here’s on thing that I would think is not permissible for statistical researches to do.

1. A hypothesis H0 has been found to have statistically significant support for rejection.

2. The researchers in question run a study, and claim that they failed to replicate the finding in favor of rejectding H0. Some would claim this statement “`One notable difference between this report and the one released in August is that we did not find a significant effect of gender on placement this time.’ ” comes awfully close to that.

3. What the researchers actually did was to, for not particularly good reason, restrict the power of their study by breaking the hypothesis in subcategories in such that a way that it is a priori predictable that the evidence for rejecting H0 would less likely to be found.

This is better, Eric. Yet I disagree that 2 and 3 are an accurate portrayal of the above.

2. We did not aim to replicate the earlier finding and I don’t think my claim makes it sound like we did. I purposefully avoided saying what the gender effect consisted of in the two cases because the cases were different–our question was different. Note that the claim you quote is immediately followed by the explanation that I suspect the superficially apparent difference is because of a change in analyses and that gender would have had a significant impact if we had performed the other analysis. (This is something I realized while writing this post, late in the evening of April 15th. If I had realized it earlier, we might have run a different analysis to check. But we did not know the results of the analysis until the afternoon of the 14th, at which point I completed the report. We had run the analyses earlier but we found an issue with the query, which needed to be updated along with a host of other tasks.)

3. I provided a reason–our dataset has more categories than permanent and temporary. If anything, we probably should have divided these out in August, but in that case too we had very little time for analysis. By happy accident we found an effect of gender. It was like discovering penicillin. (Well, in fact, I had found a difference between permanent and temporary placements in past analyses, before APDA: http://www.newappsblog.com/2014/06/job-placements-2011-2014-first-report.html . Interestingly, those who may have been disappointed that we found an effect of gender last August, when I had found no effect of gender in 2014 and earlier, did not use the occasion of their disappointment to publicly question my intentions and values. I appreciate that restraint.)

Over the next month or so we will think more about the data and what we should do next and hopefully release a more reflective set of analyses then. If you have feedback on how we might improve the project, please let me know.

Well, I would say the quoted sentence sounds an awful lot like “we tried but failed to replicate an earlier finding” in which case 2 and 3 would definitely be accurate. I think that’s probably what’s got a few people talking about research standards. Your explanation makes sense though. I should have looked for myself at how the sentence occurred in context.

In response to your request for feedback, an obvious suggesting would be to check and see if the previous finding can in fact be replicated. Can you reject the null hypothesis that

M/F is uncorrelated with (permanent hire)/~(permanent hire)

prima facie, that would seem to be both the question most people would be interested in, and the one that your study has the greatest power to answer.

The graduate student who runs the analyses, Patrice Cobb, has been working on this analysis since yesterday, around the time the post went up. We will post her results here or at the APA Blog when she is ready.

I am one of the commenters above who said that these data provide strong evidence that men are less likely than women to receive permanent positions. I am disappointed that the interesting discussion we began there has degenerated into this weird debate about whether Carolyn did something wrong. In my view, Carolyn did not do anything wrong, but either way, this whole debate seems like a pointless distraction. Surely, the important question is not about whether Carolyn did something wrong but rather about what these data actually show.

I’m with APDA fan.

Carolyn is obviously doing a huge service. It is very odd to suspect she is doing it out of bad will. And she is obviously interested in doing more, so someone who wants to see other analysis only has to make a good case for it. Come on.

Thanks! I think I’ll wait for the cleaned-up csv file. I was kind of hoping of using that opportunity to learn R, which I have been meaning to do for a while now. I also really should read that paper you wrote with Eric Schwitzgebel.

Just a quick note to make clear that, if I have no doubt that gender would still have a significant effect if we performed the same analysis as you did last year, it isn’t because I have some magical insight into that issue. It’s because except for the people that you have recently added in the database, which only represent a small proportion of the total, plus a few corrections here and there, the data are essentially the same as before. Hence, given how small the p-value was with the original data, for the effect no longer to be significant, it would have to be the case that, among the people you recently added to the database, men were *overwhelmingly* more likely to have found a permanent academic position rather than a temporary academic position, enough to compensate the pattern in the original data, which just doesn’t seem plausible at all. In fact, for all we know, if we performed the same analysis as last year on this new dataset, it’s entirely possible that the effect of gender is even stronger.

Thanks for all of your work on this. I have a question about the data. The placement rate info is striking. Just out of curiosity, I went to look at the University of Washington placement page, since that department came out with the highest proportion of its graduates from 2012-2015 in “permanent academic” positions. But their placement record seems very different than the data reported here. It seems maybe 4/9 of the graduates are in “permanent academic” positions. But perhaps there is some significant difference in how that term is being used by this report? Did you run checks with the publicly available data, or did you rely entirely on self-reported data? Just curious what explains this apparent discrepancy. (I find the apparent discrepancy a bit troubling given that it is the only page I checked…) Here is the UW placement page: https://phil.washington.edu/graduate-job-placements

Thanks for this, Alex! I started looking into this for University of Washington. It looks like we match on the TTs and 1 temporary from 2013, but the other positions listed are as permanent in our database (e.g. permanent lectureship). I don’t know if their positions are permanent or not, but if a mistake was made it would either be by the placement officer/department chair or by project personnel assigned to check the data for this program. It may be that we need to provide more guidance on what can count as permanent or temporary here, but we had intended to capture different forms of permanent contracts that may not be TT contracts. Thank you for bringing this to my attention, I will think it through some more and discuss with the other APDA members.

Also, I should say that I suspect that two of the positions in 2012 and two of the positions in 2014 are not permanent, and if I had been the one checking that program I would have changed/entered them as temporary academic positions. But I was not able to check all of the programs myself. I tried to have graduate students do this, but in the end our undergraduate RA checked these pages. In the future, I might need to work more closely with undergraduate RAs and/or assign people with more background knowledge to this type of task.

Thanks for the response. I think the big worry is if some departments are reporting information one way, and others are reporting it another way. That seems likely to be happening here. I think there is also a worry if “permanent” positions are permanent only in that the person in the position can “permanently” reapply for the same short-term contract position, or if they are in a similar relatively insecure academic position. Given that there is likely to be significant variation here in the details, I’d think it might be better to go for a sharp distinction between TT/”Lecturer in the UK” kinds of protected employment positions, and other kinds of academic positions.

This is a good suggestion–let me talk it over with the others. I do remember that some program representatives described cases like this one: a university technically only hires faculty on an adjunct basis but all faculty are treated as though permanent (I think the Naval Academy does this, for example). I thought it made sense to group those with permanent, but we might need to revisit this to help those entering data do so as accurately as possible.

This information might be helpful: I looked at the proportion of those with permanent jobs listed as TT versus other (e.g. lectureships) and found that around 11% of those with permanent positions who graduated 2012-2015 have a non-TT permanent job (such as a lectureship). This number is around 8% for graduates of all years.

I think it’s very important not to lump non-TT permanent positions together with simple temporary positions, merely on the basis of the fact that they aren’t TT. I’m not convinced that it’s necessary to treat TT as a special category of its own, but if it is, then at least there should be a division along these lines: TT, permanent non-TT, temporary.

Hi Carolyn,

Thanks so much for putting this data together. I really enjoyed looking through the charts, and found them very helpful.

I’m somewhat confused about how the job placements are being reported, and I’m wondering if you might be able to bring me clarity. It’s possible that the answers are around and I’ve overlooked them, and if so I’m sorry that I didn’t find them.

Two questions:

(1) Does the data on placements focus strictly on first-year placements (i.e. what jobs grad students got the fall after finishing their PhD’s)? Or is other placement data included?

(2) I noticed what appeared to be a couple of discrepancies and I wonder if it indicates that I’m misunderstanding the results or the way the data is reported. According to the analysis, Washington (I’m assuming this is St. Louis) placed 100% of their PhD students in academic jobs. But according to Washington’s website, in 2015 a graduate went and worked for the military in “an analytical position” (https://philosophy.artsci.wustl.edu/graduate/placement/academic-placement-record). Similarly, the analysis says that UT Austin placed 100% in academic jobs, but their website reports that in 2012 a student graduated and became an “artificial intelligence developer” (http://www.utexas.edu/cola/philosophy/graduate/placement2/byyear.php). Are these minor errors, or am I misunderstanding either a) the nature of these jobs, or b) the study results?

Thanks again, and I certainly understand if you aren’t able to answer my questions at this time.

1) In this case, it is any placement we have for the graduate, starting with first permanent placement, then first temporary placement, then nonacademic placement (except in the model, in which case it was first permanent placement, then either temporary or nonacademic or both).

2) Washington St Louis is actually shortened to Wash U. I looked back to our notes on UT Austin and it looks like the placement page was down when we tried to check it. This is the only such case in which a placement page was temporarily down (and if I have noticed this in the notes I would have looked to see if the page was up before releasing this report), but our records should have been checked against PhilJobs in this case. Here is what we have for UT Austin: 2 permanent and one temporary academic position for 2012 grads (SED reports 3 grads, PhilJobs reports 2, so we assumed 3 grads); 3 permanent positions for 2013 grads (APA reports 4 grads, SED reports 1 grad, PhilJobs reports 2 grads, so we assumed 3 grads); 2 permanent and 1 temporary positions for 2014 grads (APA reports 1 grad, SED reports 3 grads, PhilJobs reports 3 grads, we assumed 3 grads); 2 permanent positions for 2015 grads (PhilJobs reports 1 grad, we assumed 2 grads). I can see from the placement page that there are far more graduates than this and we will have to update our numbers. As you can see from Appendix B, this program did not update entries with us in summer 2015.

Thanks for all your hard work at this.

One thing that prospective grad students might want to keep in mind is that the data you used will probably be at least somewhat misleading (not saying you should have done anything differently, as I don’t know how this would be avoided!) depending on whether, in a given program, it is advantageous or not to stay enrolled as a grad student when one doesn’t secure tt employment. I’m not sure how this would affect things, but I know that at some places there is lots of teaching available for grad students and so it can often be in someone’s interests to refrain from graduating for as long as possible while trying to secure a job, whereas in other places there is very little opportunity for getting continuing funding as a grad student past the fifth or sixth year. (Another thing that might affect this, possibly in the other direction, is that it is easier for some universities to employ their recent phds as lecturers than others.) I have no idea how people should think about this when reading your data, but I suspect given the relatively short window of time you are focusing on that it probably makes a difference somehow!

Also, I just want to note that I had a similar worry to Alex’s, and I’m also just curious generally because (of course, this could just be an interesting discovery!) the overall permanent job placement rate seems very high to me given how crappy the job market seems to actual candidates. (Also, I know in some ways things were worse this year, but many of the programs that appear to normally place around 50% of candidates in tt jobs placed zero people this year…) I was expecting a far lower placement rate overall into permanent jobs and I wonder whether Alex’s observation about Washington might generalize to other places as well…

In the past, before the creation of APDA, I reported an overall placement rate based on those who were new to the job market or just graduating, but this placement rate covers graduates from 2012 to 2015 who have gotten a job by sometime between the summer of 2015 and now, depending on when that program was checked. It may nonetheless be overly high if it turns out that there are more errors of the type discovered by Alex. It does not tell us whether the placement rate has gotten worse over time, but that is something we should look into.

Here is a csv file with the program specific information in case that is helpful for checking data: https://www.dropbox.com/s/51r5kyv1h4ojdfk/APDACheck.csv?dl=0

Also, I am putting up a list of programs with known errors here: http://www.newappsblog.com/2016/04/2015-apda-report-update-with-program-specific-data-and-graphs.html

So, looking at the table starting page 16, 33% of PhDs graduating between 2012 and 2015 have permanent jobs, but 11% of these are not TT jobs (if I understand the above post correctly). So, 22% have TT jobs. That number does look somewhat realistic, but I suspect there is still inflation going on due to various factors. I think the most obvious factor that could be inflating this percentage is a selection bias.

On page 6 it says,

‘Programs were included only if we could verify both placement records and graduation numbers. Placement records were verified through placement pages and the PhilJobs Appointments page, although in a few cases we relied on placement officers or department chairs who updated the data for their own programs (see above).’

However, there is an obvious desire for programs with bad placements to hide this fact or at least not advertise it. So, I am worried the data excludes a lot of programs that would drag the 22% down significantly.

I suspect the real percentage is in the teens.

What do people think? Is this a real concern?

I think it’s a real concern; in general I still think it would be a mistake to rely too heavily on these numbers in evaluating specific programs, just because most of the absolute numbers are so low. I’ll leave it to Prof. Jennings and others to attend to technical matters of statistical significance, but the fact is if many programs have a dozen or less graduates over the measured time period then the percentages are very susceptible to dramatic statistical swings, not only because of reporting/coding but because of idiosyncratic factors relating to particular candidates. As the numbers grow over time this problem can be lessened, but only at the cost of hiding relevant information about how a program and/or the market has changed over longer periods of time.

But I do think as it improves it will continue to be a more and more accurate picture of the health of the profession as a profession tied to university employment.

One other worry about the current numbers is the (unless I missed it) lack of information about full-time vs part-time vs multiple-part-time employment. Temporary full-time employment is a very different thing from temporary part-time employment. I haven’t delved into the current report carefully, so I may have missed it. But I suspect that full-timers are more likely to be reported under temporary employment, while part-timers are more likely to be in the unknown/no information category. If that’s true, it should cause us to be cautious about our assumptions about how many of those unknowns are in full-time non-academic employment.

You write: “but 11% of these are not TT jobs (if I understand the above post correctly). So, 22% have TT jobs.” I’m not sure that’s right. What Prof. Jennings’ above post says is “around 11% of those *with permanent positions* who graduated 2012-2015 have a non-TT permanent job” (my emphasis) So I think it’s 11% of those 33%, not 11% of the total population. So, if I’ve understood correctly, about 29.4% of all PhDs graduating between 2012–2015 has a TT job.

Yea, I think you’re correct. Thanks!

With the selection bias I am speaking of, where programs with bad placements don’t have data available, I am still thinking the real percentage is quite a bit lower than 29%.

So, I guess I’ll go ahead and poke at the elephant in the room. It’s already been mentioned how dramatically PGR rank and placement come apart. Let’s look at specifics. None of the PGR top 3 break into the top 20 (the top 20!) in placement. Princeton and NYU both narrowly miss the top 20. Rutgers just barely breaks the top 35. Further, it’s not just that ‘continental’ or historically-oriented programs are managing to tie down their niche and somehow get great placement that way. UNC, Harvard, Indiana, and Michigan are, like the PGR top-3, all largely analytic programs, but they all fare much better than the top-3 in terms of TT-placement.

I do appreciate that this placement ranking does not take into account the many distinguishing characteristics of jobs, e.g., teaching load, type of institution. And I appreciate that a 3-year time span offers a relatively small sample of grads. These are all very important caveats. But still, this report seems to make pretty clear that prospective grads should not make decisions just based on the PGR. Thanks to Carolyn and her amazing team, they now don’t have to.

Right, but we have no idea whether these programs make people more place-able or just admit more place-able people. So we have no idea what role this information should play in people’s decisions about where to go to graduate school.

It’s true that initial place-ability of incoming students isn’t something that’s been accounted for here. But it’s not true that we have “no idea” whether there is any influence from the department. It would be quite shocking if the training, mentoring, professional guidance, and grad climate one is exposed to for 5-8 of one’s formative professional years had *no* impact on one’s ability to produce good work and one’s ability to then parlay that work into a sell-able job dossier. It would be really strange to be skeptical on that point.

Also, I’m assuming that students at (say) UCLA, Berkeley, NYU, Rutgers, Harvard, Princeton, UNC, and Michigan all start grad school as roughly equally “place-able.” If that’s true, and if department training has no impact, they should all end up as equally *placing,* but they don’t. So it seems reasonable to think that department climate, mentoring, financial support, etc. help explain some of the difference.

It would be quite shocking if the training, mentoring, professional guidance, and grad climate one is exposed to for 5-8 of one’s formative professional years had *no* impact on one’s ability to produce good work and one’s ability to then parlay that work into a sell-able job dossier. It would be really strange to be skeptical on that point.

Oh, of course. But unless we know how place-able they start out, we have no idea how much impact the various different programs had.

I’m assuming that students at (say) UCLA, Berkeley, NYU, Rutgers, Harvard, Princeton, UNC, and Michigan all start grad school as roughly equally “place-able.”

Well, you can assume that; I’m just noting that there’s no evidence for it. I mean, I could assume that each of those programs adds roughly equally to students’ ability to produce good work and ability to parlay that work into a sell-able job dossier, and then we’d have to conclude that some of the programs start off with much more place-able students than others. But neither assumption is warranted, really. We just have no idea how much each factor contributes.

There is definitely prestige bias of some degree.

I mean it doesn’t take much investigation to see quite a few people getting great jobs from top top programs who do not have otherwise impressive CVs.

There are also other studies on prestige bias in academia. See for example,

http://philosopherscocoon.typepad.com/blog/2016/03/a-depressing-article-on-prestige-bias-along-with-some-possibly-helpful-advice.html

Unless I’m missing something, the way programs are ranked by placement takes into account only the proportion of graduates who have attained permanent academic positions. I think this gives a somewhat distorted picture of things, for a couple of reasons.

First, compare the temporary positions of graduates from NYU and Minnesota, which are closely ranked on this data. NYU has 38% of graduates in temporary positions, and Minnesota has 46%. But NYU’s temporary positions seem to me a little better, intrinsically and instrumentally for the purposes of securing future employment, than Minnesota’s. The first three temporary positions listed on the placement page for 2015 NYU graduates are a UNC posdoc, an Antwerp postdoc, and the Harvard Society of Fellows. The first three temporary positions listed on the placement page for 2015 Minnesota graduates are Anoka Ramsey Community College, Hennepin Community College, and a postdoc at Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences. I’m not sure about other potential grad students, but I would prefer a UNC postdoc to a temporary position at Anoka Ramsey Community College.

Second, as you mention, the data doesn’t distinguish between the quality of jobs. Minnesota’s two 2015 placements into permanent positions at Minneapolis Community and Technical College count for as much as NYU’s TT placements into Indiana and USC. Again, prospective grad students might prefer a TT job at Indiana to a permanent position at Minneapolis Community and Technical College.

Third, since the data only goes back a few years, we might suspect that the programs that have placed people into relatively prestigious postdocs will move up the rankings as those people move from their postdocs into permanent positions. Programs who have placed people into relatively unprestigious postdocs and into temporary community college positions will probably not see as many students move from those positions into permanent positions.

So, although this data is indeed really helpful, and provides some information that’s just absent from the PGR, I don’t think we should be too impressed by the apparent disparity between PGR rank and ADPA rank, in large part because the APDA “ranking” ignores important qualitative factors in placement that would be highly relevant to one’s decision about where to pursue a PhD (but I don’t mean to say that it’s blameworthy for doing so, or anything). So I’m not really convinced, based only on this data, that prospective grad students who looked only at the PGR would be basing their decision on information that doesn’t correlate well with quality of placement.

Hi Jared,

Yes, of course, I agree that it very much matters what kinds of jobs we’re talking about and what one’s long-term prospects of employment are. But, I still think PGR can lead you astray here (though probably not re: Minnesota vs. NYU, as you point out). Several of the UCs, Michigan, and Harvard all do better than NYU, Princeton, and Rutgers on tenure-track employment, and I’m assuming their temporary placements of the former are roughly similar to the latter’s in terms of quality (though I have not checked that). So, it still seems to me that if a prospective were to naively think, “NYU has better placement than Princeton, Princeton has better placement than MIT, MIT has better placement than Berkeley,” etc., it looks like they could go astray, at least if TT placement in 3 years is what they’re interested in and *even* if decent non-TT short-term placement is also what they’re interested in. Of course, the fullest picture of employment prospects would look at both quality of jobs and long-term prospects, and no one currently has that data collected, but given the data we have so far, it does not seem to me that differences between PGR rankings should be taken very seriously.

I guess here’s where you probably won’t go too far wrong in using PGR as a guide to placement — if you ignore fine distinctions between rankings but treat (say) the top 15 as one band of prestige, the next 15 as the next band of prestige, etc. But if you think the PGR difference between (say) Rutgers and UNC is indicative of placement, you could be in for a nasty surprise when you’re one of the 1/3 of Rutgers grads who in a 3-year span don’t get any kind of academic placement, even of a temporary kind.

Two things:

1) the sorting of programs into proportion of permanent placements is not intended to be a ranking. It is not obvious to me that we would want to sort of that criteria alone for a ranking, but sorting by multiple criteria is visually confusing, which is why I chose to sort by a single variable. My hope is that sorting the programs helps you to look for trends and to explore the programs in more depth, relative to other programs.

2) “Minnesota’s two 2015 placements into permanent positions at Minneapolis Community and Technical College count for as much as NYU’s TT placements into Indiana and USC. Again, prospective grad students might prefer a TT job at Indiana to a permanent position at Minneapolis Community and Technical College.” This may be true, but I think we should be careful not to import the PGR into all of our value judgements–the PGR says nothing about whether working at one program is better than working at another. (I grant that you may not be doing this, but others have.) Given this, how should we measure one job against another? Is a community college job worse than a research-focused job? For almost every measure I can think of (happiness, productivity, etc.) this would depend on the person. For some, the pressure of research-focused jobs brings misery, whereas others thrive in this environment. For some a high teaching load is exhausting, whereas other love teaching more than any other part of the job. Some enjoy teaching the best prepared students, whereas others find meaning in teaching those from underprivileged backgrounds with less polish. (I know many people who primarily see themselves as teachers, and who have thought this way since before entering graduate school.) My plan is to incorporate Carnegie Classifications as soon as we are able, which will help you to distinguish programs that place in R1s versus programs that place in community colleges, but I will resist treating one of these categories as inherently better than the other. Here is an anecdote: I have a fantastic job–a 2:1 teaching load in which I determine the courses I teach (a good fit for me), amazing and supportive colleagues, truly impressive graduate students (our placement record seems pretty good for a brand new program, although I do not know how cognitive science graduates do generally–of 12 grads so far there are 3 TTs, 3 postdocs, 2 other temp, 2 industry, 1 works in education, and 1 is unknown), an undergraduate population who are invested in their education and for whom an education here makes a real difference, and a location near Yosemite National Park and other beautiful natural areas. Yet, I work at an R2 (as determined by the most recent Carnegie Classification release) that most in philosophy wouldn’t recognize and I work in a cognitive science program, which wouldn’t be a good fit for just anyone. I would love to be able to say something about which programs send graduates to the best jobs, but I am not interested in importing what I think is an unhealthy obsession with prestige in determining what the best jobs might be. I might be able to get at this with the qualitative survey–I will discuss this with those working on the survey (Gordon, Spevack, and Vinson).

Hi Carolyn,

I agree with all your points here. I realize you did not intend the ordering w.r.t. TT-placement to constitute a ranking (but I was considering what might happen if one were to treat it that way). Of course non-TT placement is also very important.

I also agree that it is silly to assume that everyone wants a research-intensive job. I was admittedly thinking just of the person who wants such a job and was ignoring the many, many people who don’t, and you’re very right to call me out on that!

Thanks again for your marvelous work on this. So invaluable!

Another elephant in the room to poke at: there are several programs that graduated zero women during the 3-year span. Some of those programs had low numbers of graduates, so the sample is too small to be meaningful. But check out Miami. 15 grads and no women!

I love this. Quantitative evidence indicates that recent female graduates outperform recent male graduates in terms of permanent full-time academic jobs (you know, the thing that the overwhelming majority of people start Ph.D. programs in order to obtain). And yet the nitpicking starts instantly, because it contravenes the expected narrative.

slow clap

I would not describe this discussion in quite that way. You are right to say that ‘Quantitative evidence indicates that recent female graduates outperform recent male graduates in terms of permanent full-time academic jobs,’ but it does not seem that there is anyone in this thread who is specifically arguing for the opposite view. On the contrary, the original post explicitly says:

In our database, 54% of the women have permanent academic positions, whereas only 49% of the men have permanent academic positions, and this difference is significant using a chi-squared test (p<.01).

Moving beyond this whole question about whether Carolyn described the data incorrectly, I wonder if you have any further thoughts about these empirical results and their implications. I mean that sincerely. Do people have further thoughts either regarding the statistical/empirical issues or regarding their normative significance?

To be clear, I also don’t think that anyone is explicitly arguing the opposite view, mostly because it’s impossible. What I’m pointing out is rather that the commentariat here is trying desperately to avoid dealing with the superior placement numbers for women by picking a variety of nits.

Personally I think the implications are pretty clear. There is no meaningful “gender gap” in current higher education hiring. To the extent that such a “gender gap” exists, it benefits women. This fits well with sociological results robustly established elsewhere: women do better than men in high school, graduate from high school more often than men, make up a greater share of undergraduates than men, and do better in college than men. Given all of this, the results of the present study should surprise precisely no one.

Because apparently I have to spell this out, no part of the above has anything to do with historic hiring patterns. Nobody is disputing that men make up the majority of current faculty, who were hired under circumstances completely different from today’s. Nobody is claiming that those historic hiring patterns make it difficult for women in the academy. Nor does my point excuse/explain situations like the University of Miami graduating 15 men and zero women. However, it’s pretty clear that once a female student enters the Ph.D. pipeline, she is if anything structurally advantaged relative to a male student. The frantic attempts by the commantariat here to divert attention from this fact would be amusing, were it not so alarming.

I don’t understand the 54% and 49% numbers, because the total for permanent is 33% according to the table on page 16.

Anyway, that women are advantaged is consistent with what I see around here where the standards for female candidates have been dropped considerably.

THOUGHTCRIME

WE HAVE THOUGHTCRIME HERE

(I think the 54 and 49 are overall in the database; the 33% figure is for people who graduated between 2012 and 2015).

I think you are projecting — no one is frantically avoiding anything, they just care about this issue less than other things about the report that are interesting.

I also wouldn’t find it all that surprising if women turn out to have an advantage. But “slight advantage” does not always, or even most of the time, translate into a job. I know plenty of talented women who are struggling on the market. It’s difficult for men and women, all of whom experience frustration and disappointment, most of whom are deserving of jobs and not getting them. The terrible injustice of the job market and employment more generally in philosophy overshadow whatever slight injustice there is (if there is one, I’m not sure that there is) in some small gender advantage.

@babygirl

1) Perhaps “frantic” was the wrong word–perhaps not–but from where I’m sitting a lot of the comments here look like deliberate attempts to downplay or deflect attention from one of the core, highlighted, most interesting and most important results. Specifically the comments of gopher, Another gopher, and Philippe Lemoine. I appreciate your comments above engaging with them.

2) I agree with you about the relative importance of the male/female placement rates vs. the overall situation with respect to employment. Furthermore, I wouldn’t even necessarily describe the difference in placement rates as “unjust.” After all, assuming that women are doing better than men throughout every level of education for morally neutral reasons, the superior placement rate of women in higher education could be morally neutral as well: shouldn’t we expect women to emerge from the education system, on average, better qualified than men? Shouldn’t the most qualified candidate get the job? Of course, the assumptions in this line of reasoning are doing a lot of work.

@babygirl,

an 85% higher chance of receiving permanent employment, as stated in the 2015 report, is not a “slight advantage.”

Actually, the previous report just gave the odds ratios obtained by the regression, it didn’t attempt to convert that into probability ratios. So 85% definitely overestimates the probability ratio for gender, which is what we are looking for. I made the same mistake at the time, because I had just skimmed through the report, instead of reading it carefully. Still, even when we transform the ratio of odds into a ratio of probabilities, the result can hardly be described as corresponding only to a “slight” advantage for women. Let me plagiarize myself by copying below something I wrote on Leiter Reports a few weeks ago on that issue:

“Based on the discussion on Daily Nous, it seems that, in the data they analyzed, being a woman increased the odds of getting a permanent position by 85%, other things being equal. However, those are *odds*, not *probabilities*. What it means in terms of probabilities will depend on the value of the other variables. But, if we take as baseline the average rate of placement in a permanent position for the whole sample, namely 53%, it corresponds to a 27.5% increase in the probability of getting a permanent position.

As I noted back then, this probably underestimates the effect of gender, since the analysis didn’t contain a variable for the number of publications and, according to previous data collected by CDJ (see this discussion: http://dailynous.com/2014/12/23/this-year-in-philosophical-intellectual-history/), men have significantly more publications on average. Thus, assuming that other things being equal having more publications increases one’s chances of getting a permanent position (which strikes me as very reasonable and, to be clear, does *not* imply that number of publications tracks merit), including a variable for number of publications in the regression model would no doubt show the effect of gender to be even stronger.”

Onion Man,

Nothing I said is an “attempt to downplay or deflect attention from one of the core, highlighted, most interesting and most important results.” Almost every comment I wrote *called attention* to that result.

I was also surprised by The Onion Man’s comment, for exactly the same reason.

Hi gopher and Philippe,

Apparently I at least partially misunderstood the intent of your earlier posts, for which I apologize.

It seems fairly plausible to me that the advantage for women is the result of the fact that women’s work tends to be better than men’s (particularly their written work, which is especially important on the market). And no, I don’t mean number of publications, because no search committee I’ve ever heard of makes hires by tallying numbers of pubs. They read writing samples and read them closely, as they seek quality, not quantity.

There’s a very good, cultural explanation for why women’s writing work might be deeper and more developed than men’s. Women are routinely: ignored in philosophy discussions; interrupted by men; talked over by men; patronized by men (rolling eyes, sighs, lack of proper attention to them when they’re talking); socially ostracized in grad programs b/c they’re not “one of the guys” (or b/c their attempts at friendship are met unwanted sexual advances); not invited as often to give talks and guest lectures as their male peers; when they are invited to give talks or lectures, their envious peers attribute it to affirmative action or to their attractiveness; sexually harassed; disbelieved when they report harassment (and even denounced by big names in their field); mocked for showing an interest in feminist philosophy; treated in a patronizing way by older men who regard their work as slight or probably derived from someone else; mocked for attempting to organize women-friendly or women-supportive events (despite their otherwise dismal social options); told on fora like this one that they just aren’t “good enough” to be in philosophy; and so on.

My suspicion is that all of these social barriers force women to prove themselves more. They often can’t do it in talks because they’re talked over, ignored, or are (some of them) simply anxious in these situations, having had too many bad experiences. But they can prove themselves in the slow, hard, humbling work of writing something that is actually original and not just another “Reply to M’s rejoinder to N’s objection.” My impression is that rather than do this hard work, (some) men content themselves with relatively narrow points and churn them out for publications, as though that is what good work amounts to.

This isn’t to suggest, of course, that we should not welcome a hiring advantage for women for other reasons to do with performance. I just think performance alone (again, writing quality, not quantity) might easily explain it. (To test this, we might enforce broad and strict anonymization of job dossiers and see who makes long lists. I for one am all in favor of this). Another reason we might wish to prefer women is that being a faculty member is at its core a service position, and the people served are undergrads and grad students. Many of these are women, and there are many reasons to think women students might benefit from having some decent proportion of women faculty. (Indeed, I wonder whether in the future, interpretations of Title IX might not require faculty representation of that kind). There are other reasons as well to do with diverse intellectual and social perspectives, the possibility of disrupting some of philosophy’s more anti-social (and androcentric) cultural elements, and so on. These points are, I hope, familiar.

You don’t provide any evidence for any of the claims you make about the existence of social barriers for women. I’m pretty confident that some of them are provably false. For instance, I doubt that women are less likely than men to be invited to give talks/lectures, but in any case if you think that’s true you can’t just assert it, you have to collect data and show that it’s true.

Even if you could provide data that support the claims you make about the existence of social barriers for women, you would still have to show that the existence of such barriers results in work of higher quality by women, which you also haven’t done. Moreover, given how strong the effect of gender in hiring seems to be, the effect of those social barriers would have to be even stronger, which strikes me as completely implausible.

As far as I know, the number of publications is the only independent measure of the quality of applicants we have data about and, however imperfect the data in question may be, they indicate that men are on average superior to women by that measure. To be clear, by “quality of the applicants”, I just mean how attractive they are to potential employers, regardless of whether the criteria they use to assess the merits of applications are justified.

So, even if you think that employers shouldn’t count the number of publications in favor of a candidate at all, it’s irrelevant as long as they do to some extent, which I think almost nobody would deny. Now, I understand that you deny it, but you’ll have to forgive me if I doubt that, had the situation been reversed and the data indicated that women had on average more publications than men, you would even have considered that possibility.

Thus, not only do you not offer any data to support the, to my mind, pretty wild conjecture you make, but in fact the only data we have that bear on your conjecture actually contradict it. So, if you ask me, I don’t think that you’re doing the cause that you take yourself to be defending any favor.

Actually I’m pretty sure “anothercommenter” was floating a hypothesis (note the language like “It seems fairly plausible to me” and “my suspicion is that”), and suggesting a way we might empirically test that hypothesis. I’m pretty sure we’re allowed to do this in philosophy, and I’m also pretty sure that the hypothesis is not going to sound that wild to an awful lot of us.

Except that we’re not doing philosophy here, we’re doing social science. Or at least we’re trying, but I see that for many philosophers, it doesn’t come easy. Now, if we’re just floating hypotheses, here is another hypothesis. Suppose that all the social barriers for women that anothercommenter posits exist. It could be that, as a result of those barriers, women in graduate school get less feedback on their work, are discouraged, receive less encouragement, etc. which negatively affects the quality of their work.

In that case, given the results of the analysis performed by Carolyn and her team, the preference for women by employers would be even stronger than is suggested by the odds ratio estimated in that regression. Given the data we have, I don’t see how that hypothesis is any less plausible than anothercommenter’s if you really believe that women in philosophy face all those social barriers, but interestingly I don’t see anyone floating that particular hypothesis. A more cynical man than me might conclude that it’s because, unlike anothercommenter’s hypothesis, it doesn’t have the “right” implications.

Similarly, I very much doubt that, if the analysis had revealed a bias for men, anyone would have floated that kind of hypothesis to explain away the result, especially if the only data we had that bore on the hypothesis in question actually contradicted it. Frankly, what bothers me is not so much that women seem to be receiving preferential treatment in hiring, as much as the bad faith exhibited by some of the people who argue that they do not.

actually, pretty sure now that I think about it that commenting on this blog post doesn’t constitute either an attempt to do philosophy or one to do social science, at least not necessarily so.

I’ve got nothing more to say except that:

(a) I believe that women grad students who complete their degrees are more likely to get a tt job in philosophy than male grad students who complete their degrees;

(b) we’ve got no evidence about what the explanation for this is, and your speculation (which it is) isn’t on more solid footing than the person you are taking such offense to’s;

(c) If you don’t see that women are systematically disadvantaged in professional philosophy/grad school in all sorts of other ways, then I can’t help, I’m not going to come up with some “evidence” that is going to satisfy you, and I don’t really care, because this is straightforwardly obvious to literally almost every single woman I’ve ever talked to in philosophy, successful or not, and to lots of men too;

(d) I’m super proud of the women who have achieved against these odds and I can’t see a single good reason, in the insanely bad market we are in currently, to not attempt to hire women when all else is equal—and by all accounts of people on hiring committees that I’ve heard, except for jobs with very narrow AOS’s, all else is equal, that is, there are a ton of highly qualified candidates; in fact, I think something stronger—we should aim to hire women when all else is equal;

(e) I find it just as plausible as the other commenter that women candidates are not just equally good, but better, than men, I’ve got massive amounts of systematic but, yes, anecdotal evidence that women are not taken as seriously, have to do more to prove themselves, are ignored, are talked over, are harassed, are assaulted, are marginalized, are not listened to, and that they have to compensate for this, if they are going to make it through the profession, by working extra hard;

(f) I honestly couldn’t care less whether you believe this. All I care about is what is happening in the profession: how departments are choosing to make hires; what they are valuing; how departments are choosing what students to admit; and so on. I’m grateful that there are a lot of people with power in philosophy who are choosing to try to change the face of the discipline. I haven’t seen any evidence that anyone has done anything wrong. (Indeed, I’m not even sure what it would take for a department to do something morally wrong in a hiring decision—I think we’re all generally over the idea that it’s a meritocracy, we know that people are looking for particular things and have narrow and weird sets of preferences, and yet I don’t think we have ever come to a consensus as a profession (nor, I hope, *will* we ever come to such a consensus) about how to rank and order philosophers, or candidates for a job (also, these things come apart, as has been pointed out above—there are many other things we hire for besides research and research potential).

(g) I think oftentimes the thing you describe—“women in graduate school get less feedback on their work, are discouraged, receive less encouragement, etc. which negatively affects the quality of their work”—occurs. I think women often end up leaving grad school without finishing because of the lack of support, encouragement, and feedback on their work. I think that women who make it through environments that are mostly hostile to us and then end up getting jobs in the worst job market ever should be applauded for managing to overcome all this crap. I think that people who are choosing to hire those women should be applauded. I also think that the thing that you describe starts earlier, at the undergrad level for philosophy, in many cases, and that that contributes towards women self-selecting out of philosophy and not applying to grad school.

I also think that capitalism sucks, that the job situation in philosophy and the adjunctification of universities is abysmally horrifying, and that we should be resisting *that*. I think it makes very little sense to be so actively angry/working so hard to oppose whatever (if any) preferential hiring is being done for women if you’re a man and you’re worried about getting a job, or haven’t yet gotten a job (well, it makes sense in that it is consistent with/is explained by the way that systematic oppression and sexism work that men would focus on this, but it is irrational). Women in philosophy are not the reason for this; the reason is that we are producing tons more PhDs than we have jobs for, and the reason for that is political, and much greater/has nothing to do with whether there is some affirmative action in favor of women on the job market. We all, but especially those philosophers who have secure jobs, and tenure, ought to be fighting against that. The anger at women in the profession is deeply misplaced. We’re not taking your jobs—it’s *incredibly* hard for women to get jobs too. It’s incredibly hard for anyone to get a job. Even if I have some slight advantage over you in getting a job—which is not at all clear—it’s still hard as hell for me to get a job. To be clear, I’m *not* with the feminists in philosophy who think that we should be intensely focusing, at the cost of focusing on the more important issue, on promoting women in philosophy. I think it’s great to have initiatives to do so, etc., but anyone who doesn’t think there’s a far more serious problem in the profession—the lack of jobs—is probably sitting in a serious position of privilege.

So I disagree with Onion Man here: I take the central lesson in Carolyn’s data to be about sheer numbers of/percentages of people not getting tenure track jobs. I take the central lesson to be that there are not nearly enough jobs for the I assume mostly well-qualified PhDs entering the market. That’s the issue that needs a fix. Whereas even if women *are* being given an advantage on the job market (which, like I said, I don’t actually believe), its effects on their male counterparts are miniscule compared to the effect of there just being no freaking jobs to begin with.

Actually, contrary to what you say, it’s clear that your explanation of the data is on more solid footing than anothercommenter’s conjecture. The data show that, even when you control for AOS and year of graduation, being a woman increases your chances of getting a permanent job significantly. Anothercommenter conjectures that it’s because women are not taken seriously and, as a result, produce superior work while they are in graduate school.

First of all, given how large the effect of gender seems to be, it would presumably have to be the case that women’s work is a *lot* better on average than men’s work. That is a very strong claim which needs to be independently supported. Now, the only data we have that independently bear on that hypothesis, namely the average number of publications for each gender, suggests that the opposite is true.

You suggest that, for anothercommenter’s hypothesis to explain the data, women’s work doesn’t have to be a lot better to men’s work, because for any particular job there are often a lot of candidates that are judged to be equally qualified. The only evidence you give for that claim is that, for any particular job, there are a lot of qualified candidates. But, from the fact that there are a lot of qualified candidates, it doesn’t follow that a lot of those are *equally* qualified.

Moreover, even putting that aside, it’s clear that anothercommenter’s hypothesis is a bad explanation of the data. As DoubleA notes below, in order to explain the data, it’s not enough that women’s work be on average better, it has to be recognized as such. But anothercommenter’s explanation of the hypothesized superiority of women’s work is that their work is generally not recognized in the profession. So it would have to be the case either that people’s bias suddenly disappears when they become part of a hiring committee, or that women’s work is so much better than men’s work that it’s enough not only to overcome that bias, but even to make them significantly more likely to get a job after the bias has been overcome.

The hypothesis that employers have a preference for women, on the other hand, doesn’t have any of those problems. In particular, it coheres with other things we know beside the hiring patterns shown in Carolyn’s data, such as the fact that a lot of people in the profession and in academia more generally are on record saying that affirmative action for women is justified.

Finally, nothing I have said implies or even suggests that I am “angry at women” and, indeed, I am not. As I already said, what really bothers me is the bad faith in this debate, which I’m sure is obvious to everyone but a handful of true believers. It’s okay if you think that women *should* get preferential treatment in hiring. I suppose that reasonable people can disagree about that. But please don’t use fallacious arguments and make unsubstantiated claims to deny that, based on the data we have, the most plausible hypothesis is that women *do* get preferential treatment in hiring, because that’s just dishonest.

A few years ago, when people were talking about the underrepresentation of women in the profession, we were told that one of the explanations was that women were less likely than men to be hired even when they were equally qualified. But now we have data that clearly show that not to be the case and, all of sudden, all sorts of ad hoc hypotheses are floated to explain the data. It’s pretty clear that, for some people, no amount of data will ever be enough to convince them of the truth of something they don’t want to accept. That’s what is annoying me.

“it’s clear that your explanation of the data is on more solid footing than anothercommenter’s conjecture” should of course read “it’s clear that my explanation of the data is on more solid footing than anothercommenter’s conjecture”

People have always been saying that women have to be better than men to get through graduate school. It may not explain the whole effect, but no, it’s definitely not ad hoc to bring it up now.

I’m not sure that’s true, but let’s say you’re right about that. In that case, the hypothesis may not be ad hoc, but it’s still a very poor explanation. As I already pointed out, the explanation for the alleged superiority of women in graduate school is at odds with the fact that superiority is supposed to explain, namely the fact that women are more likely to find a permanent academic position. Indeed, if the work that women produce in graduate school was not recognized, which somehow made it better, it would be unlikely to be recognized by hiring committees. It’s also the case that, so far, the only data we have that independently bear on that hypothesis, namely the data about number of publications, contradict the hypothesis that women produce better work while they are in graduate school. By the way, when those data were published, I remember that some people argued that it wasn’t surprising given that women were facing a hostile environment in graduate school. But now the hostile environment that women allegedly face is supposed to make their work better. You can’t have it both ways…

You’re putting a lot on anothercommenter’s particular description of the situation without considering whether there might be a better hypothesis in the same spirit, which would be normal in a less politically loaded inquiry.

I think the core of the claim is just: there are a bunch of cultural factors discouraging women from pursuing philosophy, and what makes women overcome those factors is often that they’re really good at it, enough so that women who self-select into philosophy are, on average, better than the men who do. There are also a bunch of factors that cause graduate school women to, in general, feel more of a need to prove themselves have less confidence in their work, which tends to result in stronger work.

It’s not that the value of women’s work is never recognized. It’s that women, especially in person, are less likely to be given the benefit of the doubt, less likely to be assumed to be saying something right, and so if there are ambiguities and unaddressed problems, they’re more likely to get pressed, which essentially amounts to a more rigorous graduate school experience. Because of this, women tend to spend more time per paper, and so they tend to write fewer, but better, papers. If hiring committees tend to prefer one excellent paper to two good papers (which I think is true), this would be an advantage.