The Internet: Good for Philosophy

On a recent trip I was introduced to a senior philosopher who soon turned the conversation away from the standard opening pleasantries with this: “If it were up to me, the internet—especially blogs and social media—would go out of existence. It is just a place philosophers go to do terrible philosophy and act thoughtlessly. It’s embarrassing.”

Naturally, I asked him if he’d like to write up his views for a guest post at Daily Nous.

After some hesitation, he declined, but I’ve been thinking about what he said.

Do philosophers do terrible philosophy on the internet? Of course. Just as they do off the internet. Do philosophers act like jerks and idiots online? Absolutely. Just as they do offline.

Yes, on the internet, stupidity, jerkitude, brattishness, and boorishness are broadcast further and faster than in meatspace. Yes, on the internet, we are more insulated from the emotional effects of our speech, and so, less sensitive. Yes, on the internet, the constant stream of information and communication makes us comically impatient. These are real problems that accompany our internet-saturated culture. But what alternative world are these critics of the internet imagining?

A wise professor of mine once said: “Each system has its problems. The question is: ‘which problems do you want to live with?’”

I prefer the problems of the internet to the problems of a world with no internet. The internet is home to an incredible amount and variety of philosophical information, creation, communication, and collaboration. From resources such as the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy or PhilPapers or the UPDirectory to podcasts like History of Philosophy without any Gaps or Very Bad Wizards to mutual aid networks like The Philosophical Underclass to blogs like Brains or What’s Wrong? to stores like Amazon and the Unemployed Philosophers Guild to tools like Google Docs and Skype to the helpful exchanges that take place on Facebook and Twitter to open access journals like Ergo and Philosopher’s Imprint to random collective goofiness to… well, you get the idea. Think of all the problems we’d have if we didn’t have these kinds of things.

But… I could be wrong.

Via Zac Cogley (Northern Michigan), I read a post at The Last Word on Nothing that describes the lead plumbing in ancient Rome:

In fact the Romans knew that lead wasn’t good for them. Several doctors and writers talk about the lead poisoning they saw in metal workers. Hippocrates himself described metal colic in 370 B.C. but didn’t realize it was related to lead. By the 2nd century B.C. doctors accurately described lead poisoning for the first time. By the 1st century B.C. they knew that water that flowed through lead pipes wasn’t very good for you.

But having plumbing was a status symbol. It was key for the wealthy. And many of them continued to use lead pipes.

The author, Rose Eveleth, then quotes a friend of hers:

“Maybe people will look back on what we think is the really important part of the internet, all the memey stuff and the social networks and the places where people are making all this money, and they will look back on it the way we look back on the use of lead plumbing on the part of the aristocracy in ancient Rome. Which, to them this was like ‘Oh my god this is the sign you’ve arrived, this is where the action is, we have plumbing and it’s awesome!’ And it was! It was this amazing technological infrastructure. It was beautifully made, it provided them with an incredibly high standard of living and it also slowly, gradually made them irretrievably sick and insane. It poisoned them day by day.

And we look back at it now as this thing that was simultaneously a fascinating part of how their culture worked, and the invention of a new kind of urban living but also as something that was slowly but surely making the ruling class into people who were desperately ill with terrible impulse control without ever realizing it or understanding why.”

She adds:

In other words, what if in 2000 years we look back on our current internet, and think of it as a fascinating but heartbreaking tale of hubris. A moment in time where people were consuming a type of technology they knew wasn’t good for them because it conferred status and prestige. And that thing they craved so much was slowly making them lose their minds. I think about this analogy a lot now. Some days it feels way too alarmist to me. And other days, it feels just about right.

I think it is too alarmist, and that it understates—even with “amazing”—just how valuable the internet is. But perhaps I’ve already lost my mind. I do run a blog, after all…

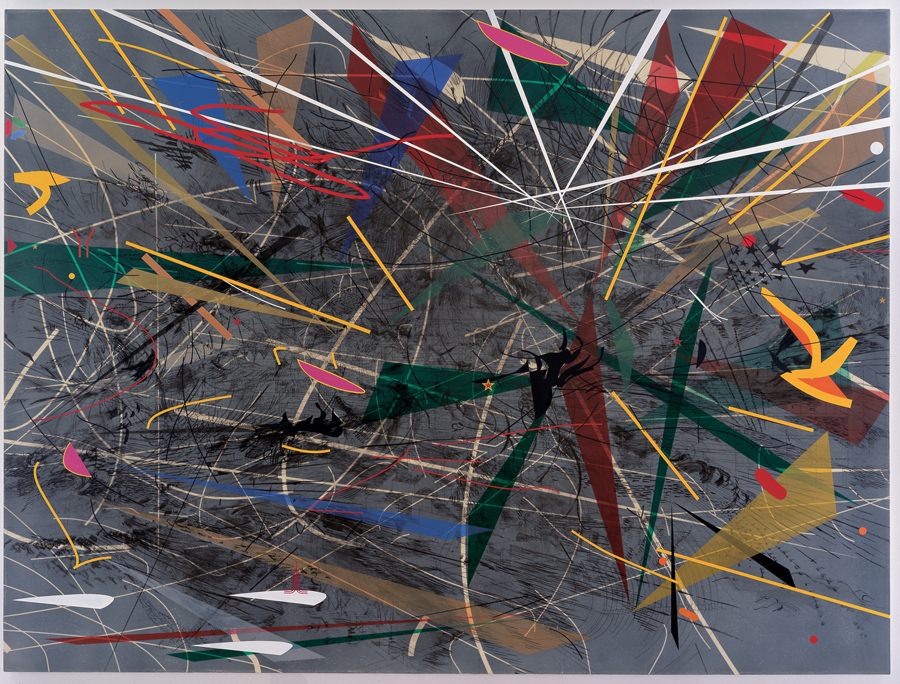

(image: detail of “Grey Space (distractor)” by Julie Mehretu

I enjoy reading the thoughts of other philosophers on current events and other things. Often I find that they have an impact on my own thoughts, and other times they can be quite comical (in terms of both laughing with and at).

Sometimes the views of others from far away geographically can serve as a breath of fresh air, even if the thoughts aren’t polished. It does happen that certain programs have a teapot that most of the people there drink from; the Internet gives us access to so much more.

So what if they laugh in 2,000 years? The Internet is a pretty good thing for us and perhaps the Romans were okay with being a bit mad in exchange for not having shit in their streets. Besides, the Mad Hatter seems to be having fun.

Pretty hard to take the general question of the internet being good or bad seriously. But it is worrying how often philosophers goof off online and start shit on social media and gossip when they probably should probably be getting back to work. I would say they are just like everybody else in this regard — though it feels pretty “high school” in philosophy and most other adults are actually answerable to someone at some point for how they spend their work day.

This question– “is the internet good for Philosophy?”– is a silly and pointless one, in my view. One might ask well ask if the written word, or sociality itself, is good for Philosophy. (Ftr, I’m not aiming that judgment at Justin in particular, who I think is charged, however unfortunately, with repeating silly and pointless questions oft-asked by people in our discipline as a matter of DN business. Bless his heart.) Justin is right, of course, that any medium that permits philosophers to converse with one another is already primed for potential conflict and unproductive interaction, but the medium is hardly to blame for that… especially given that what we see in various media (print, digital and otherwise) merely represents/reproduces many of the IRL dysfunctional interactions of our discipline.

An obvious argument *in favor* of “the Internet” qua “good for Philosophy” is the capacity of blogs, Twitter, FB comment feeds, etc to provide a more-or-less “publicly-accessible” platform for those whose views/arguments/positions/critiques might otherwise go unacknowledged and unheard because of the grossly asymmetric organization of influence in the discipline. That’s in part a socio-political argument about the current disposition and arrangement of professional Philosophy, which both generates and reproduces (and legitimizes) racist, sexist and otherwise exclusionary epistemic models– who is credited with the authority to claim knowledge and who isn’t, who gets to speak and who doesn’t, who is heard and who isn’t, who contributes to the determinations of what matters and what doesn’t– but *that* that argument is sociological is no less significant to what Philosophy is or how its done for being so.

There are a number of excellent arguments (unrelated to the bizarro and relatively-idiosyncratic organization of academic Philosophy) for the “good” of the Internet for philosophy, that is, for the interactive and productive capacity of digital exchange in the service of the development of ideas. I’ve made such arguments a number of times on my own site, but I think (super-humanly prolific and excellent blogger) John Donaher makes it convincingly in his piece “Can Blogging Be Academically Valuable?” here: https://t.co/LQM5lrHWqX

At least the immediacy of the Internet allows the time it takes to talk past one another to shrink considerably.

In Kahneman terms: the internet encourages thinking fast on thinking-slow topics.

As an heretic I feel that the internet will prove to have been completely vital for the progress of western academic philosophy. Otherwise we are stuck with the mainstream reading matter which shows no sign of it. Philosophy ceases to be a closed shop of preconceptions and becomes open to all. But I liked the analogy with lead plumbing. I fear that to a large extent this technology will prove, or is proving, to have a similar effect. Apparently, according to recent research somewhere or other, a diet very rich in meat may also have this effect.

There are a lot of problems with the internet. Social media status competitions, addiction, and general trivial information overload are particularly problematic. Philosophy blogging, however, is not one of the problems. Philosophy blogs may turn out to be considerably more important to the future health of philosophy than other more insular modes of communication we typically engage with in the field.

The net’s got 99 problems, but philosophy blogging ain’t one.

Just for attribution’s sake, the friend that Rose Eveleth quotes is attributed as digital historian Finn Brunton. (And it’s not strictly obvious that he’s a friend of hers rather than just someone who has been a guest on her podcast.)