Philosophy’s Public Relations Moment — Were We Ready?

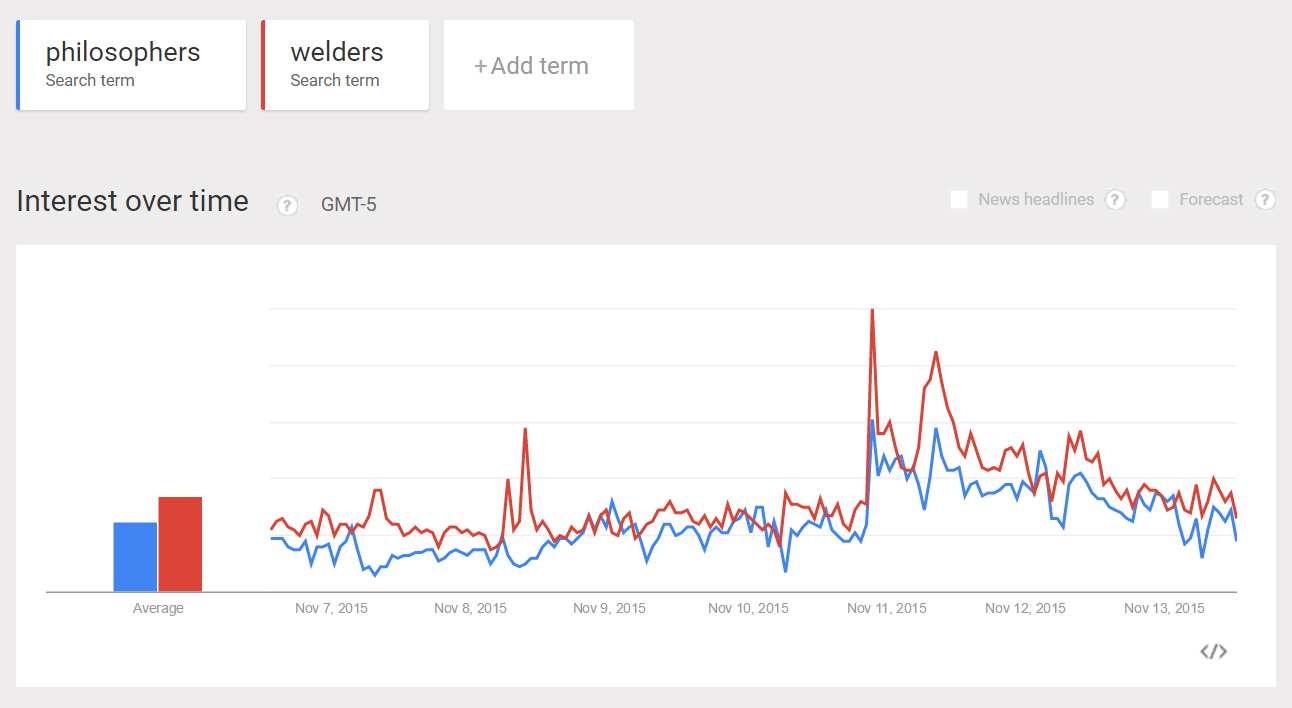

The Republican Presidential Primary Debate earlier this week led to a spike in public attention to the study of philosophy. Various news outlets covered Marco Rubio’s claim that the United States needs “more welders and less philosophers,” as well as other disparaging comments about philosophy by John Kasich and Ted Cruz (see previous post), along with responses by philosophers and others. Web searches for “philosophers” (and “welders”) spiked:

This kind of attention to the value of philosophy is rare. It is also an opportunity to inform the public about philosophy and philosophers, as its attention is so infrequently focused on us and what we do. Were we ready? To be ready would be to have talking points and soundbites prepared, data in attractive and accessible forms at the ready, and a willingness and ability to proactively reach out to media.

I don’t think we were ready.

American Philosophical Association (APA) Executive Director Amy E. Ferrer did well, I thought, when contacted by Inside Higher Ed, as one would expect from someone in her position. Her comment to them was short and informative:

Rubio’s refrain about the value of philosophy is unfortunate — and misinformed. Philosophy teaches many of the skills most valued in today’s economy: critical thinking, analysis, effective written and verbal communication, problem solving, and more. And philosophy majors’ success is borne out in both data — which show that philosophy majors consistently outperform nearly all other majors on graduate entrance exams such as the GRE and LSAT, and that philosophy ties with mathematics for the highest percentage increase from starting to midcareer salary.

Yet, a quick web news search suggests that Inside Higher Ed was the only news site in which Ferrer was quoted (please let me know if I’m wrong about that). A few other sources reported on her comment to IHE, but that was it. This seems like a missed opportunity. One of the crucial tasks of the APA is to promote professional philosophy, and that involves being able to engage with an enormous, diverse, and fast-moving media. I do not know how proactive Ferrer and others at the APA were in contacting the media following the Republican debate, but the dim results indicate that there is room for improvement.

Once again, I will urge that this is a job for marketing professionals, not philosophers. We philosophers do not have expertise in this. For example, consider how much better the statement in IHE by Ferrer (who, thankfully, is not an academic philosopher) was than that of philosopher and APA Chairwoman Chesire Calhoun in this widely circulated New York Times piece:

“It’s certainly valuable to get a vocational degree, but I think there is sort of a misperception of the value of getting a philosophy degree or a humanities degree in general,” said Cheshire Calhoun, a philosophy professor at Arizona State University and chairwoman of the American Philosophical Association. Ms. Calhoun notes that philosophy is not about toga-wearing thinkers who stroke big beards these days. Rather, she says, the degree denotes skills in critical thinking and writing that are valuable in a variety of fields that can pay extremely well. While some universities have cut back or eliminated their philosophy departments, and the job prospects for academic philosophers are notoriously bad, Ms. Calhoun argues that students who pursue undergraduate philosophy degrees tend to have a leg up when applying to graduate school. The notion that philosophy means “pre-poverty” is a misnomer, she said.

Translation: philosophy’s not about togas or beards [too bad—beards are trending], look past the cutbacks and bad job prospects, you won’t exactly be poor, and you’ll have leg up when applying to graduate school. Graduate school? Might I suggest that this message does not appear to be part of a purposeful, effective, marketing strategy?

I don’t mean to be too hard on Professor Calhoun, for whom I have tremendous respect. We can all get caught by surprise when hit up by reporters, and who knows how much they’ll mangle what one says, but nonetheless, this seems like a missed opportunity.

Philosophers did not know about Rubio’s quip in advance, and we have no idea when a public figure or big event will again give philosophers the spotlight. That is why it is important for the APA to have an effective marketing strategy in place, and for individual philosophers to be prepared to reach out and engage with media, both local and national.

Perhaps the APA should have sent out a mini press kit by email to its entire membership Tuesday night. Perhaps the APA should offer media training for philosophers interested in promoting the discipline. Perhaps the APA should have taken out an ad in The Washington Post. I don’t know. I’m not a marketing expert. But we could have done better.

That said, some philosophers really stepped up to the plate and placed pieces in various news outlets, including:

- John Corvino (Wayne State) in the Detroit Free Press: “Senators make more money than sanitation workers, but we definitely need more sanitation workers than senators.”

- Avery Kolers (Louisville) at Salon: Don’t suppose that “social worth of a profession tracks the market price it commands in the current economy.”

- Rory Kraft (York College) in the York Daily Record: “What we need are those who both can do the real tangible things that everyday society uses to function and think critically about what direction we want our future society to move into.”

- Alan Levinovitz (James Madison) at Slate: “We ignore the rigorous study of proper argumentation at our own peril.”*

- Douglas MacLean (UNC) in Time Magazine: “Who Needs Philosophers? Scientists, Politicians and Welders Do”

- Eddy Nahmias (Georgia State) in The Atlanta Journal Constitution: “What Do Philosophers Make? Ideas and Arguments”*

- David Talcott (King’s College, NY) in USA Today: Philosophers “compel us to ask the hard questions about what is truly valuable.”

- Kenneth Taylor (Stanford) interviewed at NPR: “Philosophy has the potential to do amazing things to your mind.”*

- Kevin Zollman (Carnegie Mellon) in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: “The way that philosophers have shaped and continued to shape the country we love.”*

(Please let me know about others.)

You needn’t agree with everything these philosophers said in order to agree that they deserve a big thanks from the profession. There’s still a media spotlight, if dimmed a little, on philosophy, so it is not too late for you to write something for public consumption about its value. (Op-eds in local media outlets should not be underestimated. They have less reach, but are often taken quite seriously by readers in the communities they serve.)

These matters of public image and public relations might strike some as unworthy of our time and consideration. Obviously, I disagree. I think philosophy is worth studying. Paying attention to the means by which we can best navigate the social and economic conditions in which we work is a way of preserving, promoting, and respecting philosophy. It is nothing new. In the past, philosophers had to navigate around kings and churches and were nonetheless able to produce valuable philosophy. Today, we have to navigate through a more crowded marketplace of ideas and entertainments, as well as a gauntlet of pandering politicians. The better we do that, the better position people will be in to pursue the study of philosophy.

(* added to original post)

There was this piece in Slate: http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/politics/2015/11/a_philosophy_professor_responds_to_marco_rubio_the_florida_senator_thinks.html

I have an editorial that will appear in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette responding to Rubio over the weekend (or perhaps Monday). I’ll post it here when it appears.

Kevin — I saw your piece: http://www.post-gazette.com/opinion/Op-Ed/2015/11/16/Welders-vs-philosophers-We-need-them-both-but-philosophers-take-more-grief/stories/201511160011

Nice work.

Thanks, Justin. I’m glad you like it.

Hear, hear Justin! Exactly right.

Well there’s nothing preventing those welders from also being philosophers (or vice-versa). If one needs a “marketing strategy”, it might be emphasizing philosophy as a minor rather than as a major. It seems to me to be a good compliment to almost any major.

That’s exactly my plan–Engineering major, philosophy minor, maybe a law school attempt. You never know.

I pretty much agree that, as you say, we weren’t ready. Though I could get picky here: I mean, given the (albeit few) excellent pieces that came out in response to Rubio’s foolishness, clearly *some* of us were ready.

As you say though, “these matters of public image and public relations might strike some as unworthy of our time and consideration”. My own small experience suggests to me this is quite true for far too many philosophers (though of course I’m aware of many great people who recognize the importance of public engagement). But it leads me to question the assumption that seems to be underlying your thoughts here, Justin.

Is the problem really a marketing problem?

I’m not straightaway convinced that it is, even though, as you rightly point out that whereas in the past philosophers had to navigate religious institutions, now we must navigate market institutions.

I suppose part of this will be a matter of how we’re to understand ‘marketing problem’ here. I’m reminded of a campaign launched by a dietary company (I think) last year in London, where a big picture of a scantily clad person was put up next to the question ‘are you bikini-body ready?’ and pasted all over the tube. The campaign did disastrously, faced serious backlash, and the company execs seemed to be facing a marketing problem for which they were apparently totally unprepared, given the crassness of their reposes to journalists.

But their marketing problem was a marketing problem insofar as what they were engaged in promoting was woefully misaligned with the prevailing mores of the time, and, moreover, demonstrated a total disregard for what were (and continue to be) issues of great public concern. Their ‘marketing problem’ was manifest in a misalignment of their product with prevailing societal concerns, and an apparent disregard on the part of the company for even being aligned with societal concerns.

I do wonder if philosophy’s ‘marketing problem’ can be told with a similar story; there is a problem marketing the ‘product’ but that is largely due to the product itself, and the attitude of its creators.

Now I will go cleanse myself for using the language of markets…

I applaud those philosophers who are speaking up about the public usefulness of philosophy. However, much of philosophy’s public image problem stems from an apparent lack of concern by philosophers about being publicly useful. Engagement with the public tends to be regarded as minimally important or unimportant compared to engaging other professional philosophers.

As an undergraduate of philosophy and marketing enthusiast, I wholeheartedly endorse professionally done marketing/PR for philosophy. Besides handling obvious funding concerns and public moments like this, an engagement with the whole of society would be desirable for enticing more generations of philosophers. I am (jokingly) thinking of a concept how to develop a marketing agency for philosophers/philosophy.

I’m not a philosopher by any stretch of the imagination. Though I’ve always had an interest, I ended up in STEM (Physics and CS), but many people in my life do study philosophy.

The (main) thing holding me back is the impression that philosophy is not particularly useful. I’ve thought of a lot of pseudosatirical and unbearably snarky ways of arguing it, but ultimately they feel insincere. So I guess I’ll just ask.

Give me the elevator pitch: what happens if we don’t have enough philosophers?

A world without philosophy is a world without deep and careful thought. Philosophy is particularly useful wherever it is useful to slow down and reflect. Fewer philosophers means less of this. I think it is obvious that we could use more reflection on all kinds of questions, as disparate as those about what it is to lead a good life and those about the building blocks of the universe. Professional philosophers have more time to devote to these questions, and it is a sign of a great society to be able to afford more such time.

Trying very had not to be glib, but it doesn’t come naturally to me. I’m well aware that most of what I’m saying is impression based, and correction is welcome. Not sure how replies work here, but this is in reply to Carolyn.

A world without philosophers may be a world without deep and careful thought, assuming philosophers are the only ones who think deeply and carefully. But if that’s the case what’s the benefit to the welder? How deeply and carefully they think is totally unimpacted by the number of philosophers out there.

Furthermore, a greater number of philosophers won’t, as I understand, produce any more answers or consensus. As far as I can tell, philosophy as a field has no interest in “settling matters”.

In a world of many more philosophers, a welder has many more people deeply and carefully thinking about what it all means, how to be good, and whether happiness is meaningless*, but he’s no closer to finding out any answers to these questions.

* these presumably are the philosophical equivalent of technobabble. Apologies.

In fact, short of pulling up census data, how is the welder to know whether or not there are enough philosophers?

You make some good points, David. Philosophers speak with and write for non-philosophers, which is how the ideas are able to spread and take on new life. Yet the non-philosopher is not a passive recipient of these ideas and uses them for her own purposes. When movers and shakers take hold of the fruits of philosophy, philosophy has the potential to impact everyone (e.g. Thomas Jefferson as inspired by John Locke, Albert Einstein inspired by Ernst Mach, etc.). Philosophy itself is so diverse and so old that it is difficult to speak sensibly about it, especially in the “elevator” format, but I think you are right to say that consensus is not the primary aim, if only because the questions and problems that philosophers aim to solve are always evolving. All of that said, I take philosophy to be something potentially shared by everyone, and philosophers to be anyone who has engaged with philosophy–I don’t think Rubio was restricting himself to a discussion of professional academic philosophers, but even there I think these comments hold.

We will be deprived of people who have a passion and a knack for asking questions and trying to find connections where most people don’t. In just a few days time, more connections have been drawn between philosophy and welding than ever before in human history. Some are funny. Some are merely clever. But it might also be that some will turn out to be insightful.

But in a way to ask why we need philosophers is very much like asking why we need people who study art history. The question itself presupposes that human inquiry and curiosity ought to be directed somehow toward producing goods and services in order to be of value, and that human activities that do otherwise deserve scorn and derision.

“A world without philosophy is a world without deep and careful thought.” Agreed. Unfortunately, it wasn’t philosophy that was directly at issue in Rubio’s claim, but philosophers – presumably meaning professional philosophers. Equally unfortunately, it is a leap – and one challenged by the history of the discipline itself – to suggest fewer (professional) philosophers means less careful thought, or even less philosophy. It strikes me as difficult in the extreme to use the value of philosophy to justify the existence of a professional class devoted to philosophical questions, one whose time for intellectual pursuits is purchased in part at the expense of those who must work more basic tasks. There’s almost a strange kind of trickle-down intellectualism implicated in this view. In any case, I think one should see the task of justifying this as a much more daunting one than suggested – one the difficulty of which is added to, but in no way caused by the anti-intellectualism that animates much of American culture.

Here are some ways that a professional philosopher earns her pay: 1) she is an expert in reasoning and so is more capable of reasoning well than a novice, 2) she is an expert in a particular topic or set of questions and so is more capable of accurately discussing that topic or set of questions than a novice, 3) she is an expert communicator, especially in writing, and so is more capable of communicating her philosophical findings than a novice, and 4) she is an expert in teaching and so is more capable of conveying the lessons of philosophy to the novice. These skills justify her position and make sense of why others want to pay her for her work. I suspect that the issue for Rubio and others is not professional philosophers, per se, but professional philosophers who fail to share many of the values of Rubio’s political base (e.g. religious values), making the skills I mentioned all the more terrifying for that base.

For those considering communicating with the press, I would strongly urge your comments be submitted in writing rather than verbally. Among the items I spoke to the NYT reporter about that did not get mentioned in this brief piece were: the scores philosophy majors get on the GMAT, LSAT, and the analytical reasoning and writing portions of the GRE are the highest or one of the highest; philosophy majors have the highest median incomes of humanities majors; the number of philosophy majors varies by institution (at ASU ours is going gang busters), but my sense is that enrollment in philosophy courses is increasing and very strong; specialized majors such as those in morality, politics, and law do very well; there is a general cultural ignorance in the US about what philosophy is and what philosophers do (not shared in Europe or Australia where philosophy is regarded as a valuable field) that affects even university administrator’s decisions about which programs to cut; the perception that philosophy is not relevant is false; in part due to institutional emphasis on addressing real world problems, philosophy has moved in this direction ( here I mentioned courses in medical, business and environmental ethics, and work on food justice as examples). I did not utter the words “pre-poverty.” It’s an excellent thing that we have this opportunity to publicly address the value of philosophy, and I hope many will seize the opportunity to do so.

The philosophy of welding?

http://www.nationalreview.com/corner/426925/philosophers-and-welders-yuval-levin

Before class after the Republican debate I brought up Rubio’s remarks and mentioned the relatively high salaries philosophy majors make. One of my students said, “Critical thinking is a valuable skill. Who knew?” This seems like a good elevator pitch.

(As for the philosophers vs. philosophy majors argument, if we’ve accepted that it’s good for there to be philosophy majors, then there need to be people to teach them, and to develop the things that they’re being taught.)

Most of our majors do not become philosophers. Most of our credits are not taught to majors. So — the question is ‘why should people who are not going to become philosophers study philosophy?” And the answer is: because studying philosophy — learning how to think philosophically — contributes to people’s ability to engage in solving problems for which nobody can give them an algorithm. This is something that everyone needs to do in their personal lives and as citizens, and most people who graduate college will need to do in their professional lives.

This is a good answer to the right question, but only if our teaching actually reflects this goal. Does it? Or does it actually reflect the goal of producing professional philosophers, or some other set of goals? I’m not sure; its something we don’t discuss much, and should discuss more, and I don’t think it is at all obvious that, eg, our undergraduate curriculum or instructional techniques are appropriate to the goals that make for the good answer.

“It is nothing new.” Hits the bullseye! Philosophers have been defending their profession since 450BCE*. If people don’t observe the benefits now more than ever they are not engaged in life with their eyes open or their minds engaged.

*The Trial and Death of Socrates -Plato

I assume we can all agree that an ethical public relations campaign is one that does not whitewash the client.

I was troubled, but not at all surprised, by the unapologetic classism and privilege that was evinced in the previous thread on Rubio’s comments. Some of these published commentaries and comments on this thread show the same breezy, unreflective classist tendencies (really, CDJ? A world without philosophy is a “world without deep and careful thought”? Maybe I should let my dad know about that; I would describe him as a very deep thinker even though he did not go to college. The horror, I know).

Phosophy is often perceived as a way for rich white men to pass the time. The cluelessness that philosophers regularly show, especially when the topic concerns class, race, or gender, contributes to this general perception. But we don’t need to hire a PR firm or get our message together because this cluelessness shouldn’t be whitewashed. Instead we need philosophers to lift their eyes from the latest epicycle of pointless responses to responses to responses to responses to something Rawls or Lewis said in a footnote and take seriously the important, big philosophical questions that life in the 21st century presents.

If philosophers continue to evince utter cluelessness about class, race, and gender, the world will consign philosophy to the dustbin of history. And no PR campain is going to prevent it.

A world without college degrees in philosophy is not the same, to me, as a world without philosophy. Your father sounds like someone who would keep philosophy alive. In my view, the oral traditions in Sub Saharan Africa count as philosophy, for example (e.g. what is transcribed by Oruka).

Nice try, but this is a discussion about whether academic philosophers should embark on PR campaigns extolling the virtues of academic philosophy. Please don’t insult people by claiming that by “philosophy” you meant any system of deep thought; that would render your original comment a tautology, and it would not be a response to the topic of this thread.

I can see that you are interpreting my comment in a way other than it was intended, but I think that read makes less sense than the intended meaning. Note that I distinguish between “philosophy,” “philosophers,” and “professional philosophers,” as does the original post (e.g. “This kind of attention to the value of philosophy is rare. It is also an opportunity to inform the public about philosophy and philosophers…”). I did not interpret this post or Rubio’s comments to be limited to professional academic philosophers and I don’t see any reason to limit either “philosophy” or “philosophers” to that.

The extent to which the first sentence of my comment is tautologous makes sense, given that it is an attempt to put forward a particular view of what philosophy is centrally about (i.e. deep and careful thinking) as opposed to, say, what computer science is centrally about (i.e. information, computers, and computation). In any case, I agree with some of what you say in that I think it would be good for academic philosophy to extend its scope.