What Should Academics Do About Journal Prices?

All six editors and all 31 editorial board members of Lingua, one of the top journals in linguistics, last week resigned to protest Elsevier’s policies on pricing and its refusal to convert the journal to an open-access publication that would be free online. As soon as January, when the departing editors’ noncompete contracts expire, they plan to start a new open-access journal to be called Glossa. The editors and editorial board members quit, they say, after telling Elsevier of the frustrations of libraries reporting that they could not afford to subscribe to the journal and in some cases couldn’t even figure out what it would cost to subscribe.

The above report is from Inside Higher Ed. The news, which broke on Facebook last Friday, prompted Professor Lee Walters (University of Southampton) to write to me about his concerns about philosophy journals, and to share data he has collected.

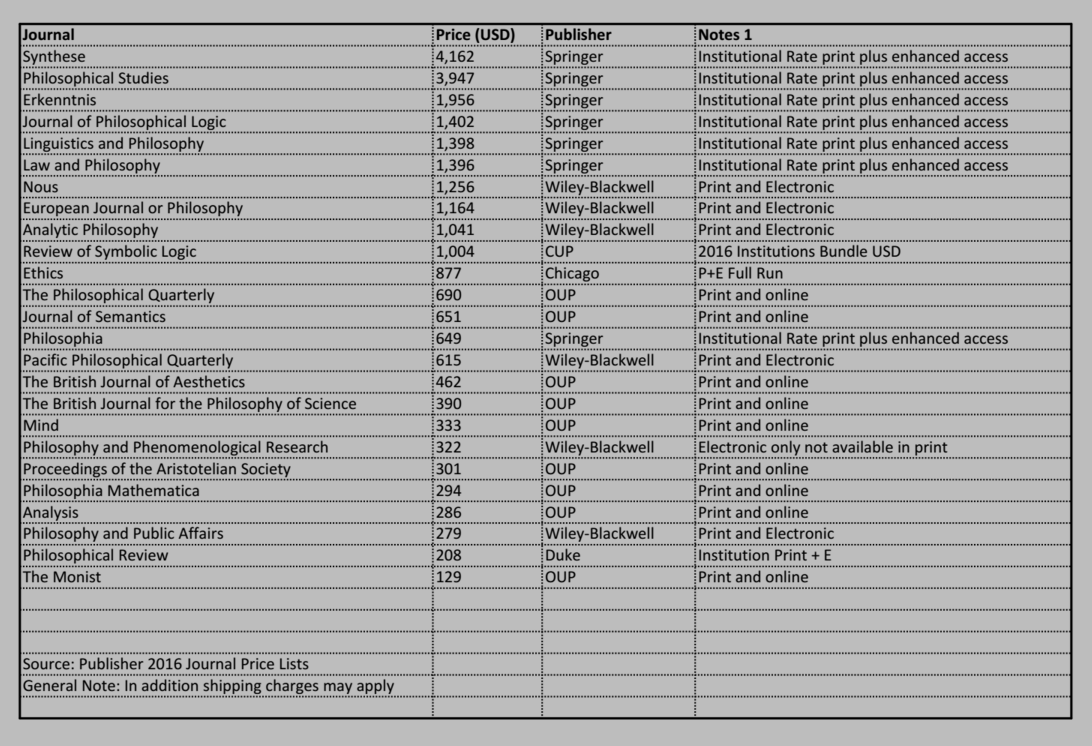

As has been noted many time before, it is ridiculous that we continue to do the majority of the work for journals and yet publishers charge the universities we work at the prices that they do. Please see the attached spreadsheet that I have compiled that shows the current institutional subscription rates for a number of our journals. I think a pattern emerges. As you can see there is huge variation in the fees that publishers charge. I realize that it is very difficult to directly compare journals without further data, since the number of articles that journals publish in a year varies, and presumably the precise package offered by each publisher varies. Moreover, some of the publishers put back some of the cost of subscriptions back into the profession. I’m thinking here of some the OUP journals, for instance the bodies associated with Analysis, British Journal of Aesthetics, British Journal of the Philosophy of Science, and Mind all fund things like conferences, research fellowships, graduate scholarships and prizes. And perhaps other publishers do this too. But putting all that to one side I think we are in a position to draw some preliminary conclusions.

The next question is what we do about this, assuming we want to?

He notes the development in linguistics and discussion of one in mathematics, and says “Maybe a focused boycott of some journals publishers with respect to editing, reviewing, submitted could have an impact.

Here is part of Professor Walters’ spreadsheet:

The entire spreadsheet, with more information, is available on a publicly accessible Google drive. Thanks to Professor Walters for gathering this information.

In his correspondence, Walters notes the increase in the number of open access journals in philosophy. Giving increased attention to those alternatives may put some market pressure on the pricing of the traditional journals.

Discussion of what, if anything, philosophers should do about journal prices is welcome. Journal editors and publishers are encouraged to comment, too.

It would be interesting to know how publishers arrive at prices for their journals…

So Springer is expensive and OUP is cheap. But what is boing on with Wiley-Blackwell? What would justify Nous and PPR being a grand apart?

I suspect it’s that the price for PPR is listed as “electronic only” while Nous is print and electronic.

Also the Nous price covers Philosophical Perspectives and Philosophical Issues as is noted in the full spreadsheet. It is difficult to make direct comparisons for the reason noted in the main post. For all I know, the Nous package provides three time as many papers/pages than PPR. The spreadsheets are all publicly accessible so people can add additional information if they have it. But before I went down that route, I wanted to start a discussion and see what, if anything, people had an appetite for.

Trying to organize to put pressure on journals to decrease prices is a horrible idea. At best, if it works, it means that the wealthy western universities will continue to be able to afford the journals, but we will continue to leave all other universities, academics in third world countries, students in community colleges and a host of other people who are not part of the privileged to 1% in academia with extremely limited or no access to current research. We will be complicit in perpetuating the cycle that privileges of the privileged and keeps the unprivileged out. We need to leave commercial publishers behind and start open access journals that are not connected to commercial publishers at all. Exactly like the linguists mentioned in this post did. That is the only viable term solution. It is certainly the only socially responsible option.

This may be a bridge too far for this particular fight, but it might also be worth questioning why we have to use journal and journal-like entities as a vehicle for publication, when we’re all capable of our own open-access publishing. (I mean: We can put PDFs on the web.) Journals serve a curatorial function, and also a credentialling one–we might be more likely to look at a paper if it appears in Journal X, and hiring and tenure committees definitely like to see journal publications on your CV. But is that the system we’d design if we were designing one from scratch?

You are preaching to the choir. My most recent paper, on temporal consciousness, is not going in any journal. I have ‘published’ it myself, under creative commons copyright, and it is available on philpapers, academia.edu, and my website. (And just to be clear, I’ve published in top-tier journals, I know what highest quality work looks like, and this paper is of that quality — it’s definitely not a second rate piece of work.) And that’s is how I’m going to make my philosophical work available from here on out, except in cases where I am co-authoring with someone. This won’t work for everyone. I’ve got tenure and a track record in the fields I publish in, so I’m not seriously sabotaging my career by leaving the academic journal model behind. And I’m not saying that what I’m doing is universalizable. But the current system is broken in many ways. Though a great deal of what is broken about it would be fixed if we would ditch commercial presses and make everything open access. The SEP and Philosophers Imprint are great examples of highest quality venues that aren’t perpetuating social injustice. Let’s have more open access journals, and an open access monograph publishing system. But in my own case, I’ve freed myself from the current model entirely. It’s an amazingly good feeling to produce philosophical work such that the end product is exactly how I want it to be — in terms of word count, what is said and not said, whether the structure is too X or too Y according to some referee or journal editor. Taking creative control of your work back from the “labels” is great.

Excellent, Rick!

I don’t mean to disaparage open access journals–they do great work. But I think one reason that we don’t have more of them is that they are (I presume) a lot of work to start and maintain. If those who don’t need support from the journal system stop using it–I mean, those philosophers who don’t need the journals for tenure, or for their job search, or to get people to read what they’ve written–then maybe we can reduce the pressure on the existing journals, and people who are sending out papers will find it easier to send it to open-access journals.

Unfortunately, at many schools at least, the administration would like a count of articles published. Not sure how a journal-free system could adapt to that.

Hi Rick, I don’t think it’s a horrible idea, but I realize it isn’t perfect for the reason you give and others. I wasn’t recommending that or anything else – I’m not in a position to really. Rather, I wanted to start a discussion and see if others had the appetite for change. This debate isn’t new and has been knocking around philosophy blogs for a number of years now. But not much has changed with respect to these journals, although on the other hand we do now have some fine open access journals too.

In addition to the obvious (not refereeing for, editing for, or submitting to such extortionate journals), we can also pressure our university libraries not to pay these fees, instead shifting their funds to support open venues like Philpapers. Those of us at universities whose libraries are being slashed *anyhow* are presumably in the best position to push for this. Publishers will presumably only reduce their prices when they see universities decline to pay them.

In addition, while I agree with Rick Grush’s comments above, I think there’s no need to agree on the final goal for us to take effective action. Whether the goal is merely to lower prices or to do away with commercial academic publishing entirely (or anything in between), the next few steps are presumably the same: do what we can to shift resources (our own and our universities’) away from them and towards more responsible venues.

Here are a few points academics may want to consider, though I certainly am not an academic; however I care quite a bit about academic philosophy and open access. I’ll break this up across two comments. The first, herein, concerns OA policies, which are usually instances of/promote green OA.

1. Does your institution have an Open Access policy?

>> If so, look into what it entails. Typically, an OA policy will ask you to deposit your final manuscript to your institution’s repository once the paper has been accepted for publication. Good OA policies will allow authors and readers alike to do more with the deposited paper than they may otherwise be able to do with the final published version (owing to copyright restrictions imposed by the publisher upon the author’s signing of a rights-transfer agreement).

Not sure if your agreement with a publisher conflicts with your institution’s OA policy? Either (a) look up the terms of your agreement or review the journal’s policy, or (b) check out the journal on SHERPA/RoMEO [1]. See if your publishing agreement will allow you to self-archive beyond your faculty web page or institutional repository. If so, deposit to PhilPapers (rather than merely indexing the paper), arXiv.org, CogPrints.org, the PhilSci Archive, SSRN and SSRN-Philosophy. NB: Academia.edu is extremely popular, but I can’t say I recommend it from an open access perspective [2].

>> If not, Peter Suber and others have developed a resource – “Good practices for university open-access policies” – as part of the Harvard Open Access Project [3]. Those interested in developing such an OA policy may want to write a letter of support to pertinent individuals at your institution. If you’re not sure who, perhaps ask your department chair or your institution’s librarians if they may direct you to a specific office or person.

Links from above:

[1] http://www.sherpa.ac.uk/romeo/

[2] http://www.plannedobsolescence.net/academia-not-edu/

[3] http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/hoap/Good_practices_for_university_open-access_policies

Thanks Colleen. Many philosophers do deposit their papers with their institution’s repository and also with PhilPapers. And this is obviously a good thing to do. But it is still a second best option, since if someone wants to refer to the paper they’ll need to see the published version, and I’m not sure how many journals allow author’s to deposit the published version.

Yes, philosophers are already making use of institutional and subject repositories. I do wish more would self-archive (at least) via PhilPapers, particularly those who use a combination of Academia.edu and faculty web pages to the exclusion of better alternatives. (Of course, this is difficult to do if one’s agreement with a publisher allows only the posting of a pre-print to a personal/institution-hosted web page.)

And yes, efforts like these still do not resolve all the problems with access, re-use, and author rights retention (even when bolstered by a good institutional OA policy). Green OA is the low-hanging fruit of the OA world. But I still think there are good reasons for pursuing it alongside gold OA.

When these topics come up on DN and elsewhere, I see a lot of confusion about what OA is, what it entails, and how “open” is different from free-to-read. My aim with the comment above was just to present some information about green OA and, more specifically, green OA via institutional OA policies to those who may not know where to start (even if they know of, and use, the repositories to read others philosophers’ works).

Gold OA certainly has many more benefits! And from the comments here, I think others may find that Open Library of Humanities is a viable alternative to traditional publishing, as OLH is a non-profit consortium of over 100 institutions globally who share the costs of publishing OA journals, do no charge author processing fees, and are all CC-licensed (I *think* all articles are CC BY, but that may not hold universally). My comment below this one deals more with all that.

Here’s the second comment regarding open access. Specifically, this comment deals with gold OA, or open access publishing. (Hopefully my comments will appear in chronological order.)

2. Support open access publishing

>> Philosophers are surely aware of open access journals such as Philosopher’s Imprint, Ergo, De Ethica, Feminist Philosophy Quarterly. These are good alternatives to traditional publishing!

>> Beware of publishing one-off articles openly through subscription-based journals. Do it if you’d like, but if the idea here is to get out from under the yoke of traditional publishers, then this way isn’t a very good one. Publishing an article in this way (i.e. hybrid access) can be quite expensive, as authors usually bear the cost of publishing the article, which may lead to double-dipping by publishers. I don’t want to talk too much about hybrid access because I think it’s of little value compared with other efforts. Peter Suber has a post on the topic from 2006, which provides a nice overview even for today [4].

>> Consider checking out the Open Library of Humanities (OLH) [5]. This is a refreshing model for OA publishing in the humanities which, I think, has the potential to put real pressure on subscription-based journals. Read more about their OA model at [6] below.

Links from above:

[4] http://legacy.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/newsletter/09-02-06.htm

[5] https://www.openlibhums.org/

[6] https://about.openlibhums.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/2015-Summary-of-OLH.pdf

3. Write your librarians about Open Library of Humanities

>> If you are interested in OLH and want to ask your institution to join, please do write your academic librarians! I have just co-written a letter to Boston University about OLH, which I’ve linked at [7] below, and which may be of use as a model. In the letter, we talk a little more about the benefits of OLH and how OLH, as an instance of gold OA publishing, avoids several problematic features of green OA (i.e. the type of OA endorsed by OA policies). In fact, OLH avoids some of the problems often associated with gold OA as well.

Link from above:

[7] OLH letter of support as an example: https://goo.gl/WszGPX – NB: Sorry that this is available only as a PDF currently.

Just updating my own post here: Looks like Glossa — as mentioned in the IHE article from the OP — will be hosted by Open Library of Humanities. Fantastic.

Awesome stuff. Thanks for the info!

Can we talk about monographs as well. When did it become the norm to price them outside the reach of the average researcher, let alone student?

Love the easy-to-answer questions. It became the norm when commercial publishers realized that almost all libraries at research universities would be all but required by their faculty to buy the books regardless of price, and that enough well-paid academics in the “1%” would still buy them. And again, the fact that they are then another instance of current research being out of reach of people not already at the top isn’t a consideration. To take one example, a while ago when I was railing against commercial publishers online, I got an email from an instructor at a community college on a native american tribal reservation, who informed me that not only could his college not afford any journals or books, that the only academic work his students had access to were a handful of books and one journal subscription that he had to pay for out of his own underpaid pocket. And to the point of this discussion, just getting the commercial presses to return the subscription prices to their rates from 10 or 20 years ago doesn’t solve this problem. Faculty at research institutions are blissfully out of touch with the realities of the 99%, and continue to support the current model and commercial presses.

When was that?

When was I contacted by the community college instructor? It was a while ago, actually. Around 2004-2005 or so, if I remember correctly. He wasn’t a philosopher, but was in lit or something like that.

Hi, I don’t know much about this, but David Velleman recently published an open access book https://sites.google.com/a/nyu.edu/jdvelleman/ and John MacFarlane has a freely available pdf version of his OUP book on his website (both of these are on relativism, so is this part of some conspiracy to corrupt the youth?). So there are options for making monographs more accessible.

These are positive steps, at least in terms of *one* of the problems with commercial publishing. Though another problem, in addition to whether folks without $ can access the book or article, is whether libraries will pre pressured to spend $ to acquire the resource. Fo0r example, I don’t know the details of MacFarlane’s book, but my guess is that if it’s published with OUP, then a lot of libraries spent a lot of their limited budgets (which ultimately go back to student tuitions and taxpayer dollars, and leave institutions with less money to hire full time faculty as opposed to adjuncts, etc.) on copies of that book. The basic problem is commercial publishers. The entire business model involves getting $ from academics and/or students and/or libraries. We need to extricate ourselves from commercial publishers.

I’m writing as a publisher, and I want to ask a question. Why does no one ever think that the solution might just be for universities to increase the acquisition budgets for their libraries instead of slashing them? The output of scholarly literature increases by several percentage points per year, and yet academic library budgets have been routinely cut, or at best kept flat, for years now. In the face of this reality, it is impossible for publishers to do anything more than ameliorate the situation by keeping their prices as low as possible. Many, but not all, publishers do this, and it is unfortunate that the few gigantic commercial firms are taken to represent an enterprise with hundreds of other participants, many who operate with very different values and practices.

Librarians have devoted the greater part of their energies, not to trying to have their budgets increased, which would represent a very direct solution to the problem, but rather have devoted themselves to the indirect, and so far not particularly successful experiment of Open Access. This incidentally, still requires plenty of money to come from somewhere in order for all the crucial tasks that are required that are not performed by academic editors. (If anyone thinks that OA has been transformative, I suggest a read of this statement from the Wellcome Trust (http://blog.wellcome.ac.uk/2015/03/03/the-reckoning-an-analysis-of-wellcome-trust-open-access-spend-2013-14/).

It seems that the one potentially effective course of action is for faculty to make the case together with librarians. It may simply be that no one thinks that this would have the slightest chance of succeeding. In that case, I see no change to the same stalemate that has been going on for decades now — some librarians date the beginning of the “Serials Crisis” to the 1970s. The subscription model is the only one that has the flexibility to ensure a high level of quality across all disciplines, including those that receive no funding because they are perceived as having low instrumental value.

In an ideal world, of course, all education and healthcare would be subsidized by the state, which in the US would be at least theoretically possible given the size of the defense budget. I feel confident in saying that of all solutions, this would strike the majority of readers of the least plausible scenario of all.

Michael Magoulias

Director, Journals

University of Chicago Press

The article that was linked discussed APC Open Access specifically. This is quite unlike the OA venues that are being discussed here (for those not aware of the acronym, APC is for Article Processing Charge, a model by which publishers, often commercial publishers, will make an article Open Access if the author pays a large fee. Some institutions have programs to pay such fees, in an effort to support OA publishing). If your point is that APC is a bad model, I agree. What we need is to move academic publishing to sources such as Philosophers Imprint and SEP and NDPR.

Open Access funded via public means isn’t implausible at all. SEP has a great deal of state funding, through the UC Library System and other sources for example. And one could hope that as more academics become better educates about the benefits of open access, and the inherent problems and injustices associated with commercial publishing, the balance of support will start to shift. The quality of PI and SEP is as high or higher than comparable commercial venues, and lacks the social evils associated with the current commercial publishing system. The hope is that more and more academics will shift to OA, creating both a need for more OA journals, as well as the practical push to actually shift library budget expenditures from commercial journal subscriptions (and monographs, etc.) to hosting/supporting OA journals, references, monographs, etc, like UM does with PI.

Since university presses are cheaper than commercial publishers, one thing that can be easily done is that those journals should move to university presses. First, there is no reason to use a more expensive service for similar products (Springer is actually the worst system, in my opinion). Second, although it still costs money, it significantly reduces the financial burden of libraries. Third, I am more happy to see the profit going to the university presses in exchange that the university presses publish more monographs at affordable prices (the books by Springer are just too expensive to anyone). Finally, it’s easier for academics to pressure university presses to lower their charge.

So I think that APA should issue an announcement that encourages journals to move to university presses. Once many journals do this, we can boycott those staying with commercial publishers.

A question for journal editors: What obstacles make it hard for you to do what the editors of Lingua did? Or to put that the other way around, what advantages do you see in working with your publishers? (I’m not asking this in an accusatory way. I assume there are obstacles to abandoning your publisher. I’d just like to learn more about them.)

In response to David Morrow: publishing the BJPS with OUP has the following advantages: 1. copy editing. Now, I know our asst ed will be raising her eyebrows to the point where they lift clear off her forehead when she reads this, given some of the problems she has had with our copy editors lately, but on the whole it is to our advantage to have the publisher take care of arranging and overseeing this process. Maybe its not so crucial for some journals but for those of us who publish quite technical pieces with all the symbolic apparatus that may involve, having to sort this ourselves would be a major obstacle to going it alone. 2. publicity etc. Again, one might sometimes wish publishers were more responsive, more fluid in their advertising etc. but again, there’s an advantage to having someone else organise the posters, flyers, sample copies etc; as well as cross-linking on their website. 3. archiving. When the BSPS last put the journal out for bids, this was a major concern. The BJPS has a rich heritage and the society wanted to ensure that all back issues would be archived appropriately and permanently and made available. 4. hosting. Editors come and go, the BJPS lives on forever (!) via the OUP site, with all the attendant apparatus, including Manuscript Central, so the newbie can just strap herself into the control seat and start allocating referees pretty much from scratch …

Of course, one could have all/most of the above with open access but the costs would still have to be met and certainly there is no way that my University, for example, would be prepared to take them on.

And finally, as was already mentioned, a significant chunk of what the BJPS earns goes to the society, where it is used to support PhD scholarships, conferences etc. (last year the society received over £100, 000). Of course, there are other ways to provide such support (all philosophers of science could tithe to the BSPS, PSA, ESPS and so on!) but this seems a useful way of channeling funding to people who might not otherwise get it.

None of the above are knock down of course but they persuade me, my co-editor Michela Massimi and the BSPS in general to keep the journal with OUP.

Thanks Steven. I don’t think BJPS is really in the firing line here, but it is good to hear what advantages low cost journals have over open access, and vice versa. In any case, as you say, there is no free lunch here – someone has to pick up the tab, and it is not clear that university subscriptions are not a good way of doing this. When Phil Imprint started charging submission fees that didn’t go down too well, but as I said the money has to come from somewhere. It is just that some journals are extracting quite a bit more money than others.

I really hate to be the loudmouth here, but … go to a computer that isn’t yours and isn’t on your university network. Maybe a coffee shop somewhere. Log on to BJPS website, or just about any other commercial press journal website, and try to get an article. Congratulations, you’ve just discovered what it’s like for the VAST majority of people in the world who want access to philosophical work. Namely, you don’t get to read anything unless you have a credit card and can pony up what in your country might amount to a full day’s wages or more for one paper. Students in Mexico, native American reservations, freshman philosophy students in the US at a community college who will be trying (and failing) to make the jump eventually to a good grad school because they’ll be competing for those spots with their wealthier counterparts from Harvard who have access to cutting edge research at will, anyone in eastern Europe or almost anywhere in Africa. Now log on to an open access venue. Is BJPS in the firing line? No, but it probably should be. We, and by “we” I mean the folks who are at top research institutions in western countries, the 1%, by and large have NO IDEA WHATSOEVER what it’s like for 99% of the aspiring academics in the world. We’re in our nice little bubble where we have access to pretty much everything we want. We should take this more seriously than we do. Again, sorry for being the loudmouth. We talk a lot about marginalized groups not having a voice. They have zero voice in this discussion. And even though I’m a 1%er myself, I’m trying to help give them a voice.

Hi Rick, I really like what you say here. Thanks for all your comments in this thread.

Hi Rick,

I think it’s important that we think about the 99% – it certainly wasn’t on my mind when I raised the issue. I don’t think we’re ready to abandon journals altogether – rightly or wrongly – so assuming we continue to have journals who pays for them? I don’t know how much the running costs of a journal could be reduced to, but there will be some costs. I think David Velleman detailed these on Leiter a while back. The costs have to be covered, so who pays? I’m aware of three models – 1) subscription, 2) a consortia of universities pay the operating costs 3) submitting authors pay, perhaps with the help of their universities. What model from these or others would you go for?

Great question. I’d go with 2. University librarians are very aware of this issue. They have massive chunks of their budgets going to pay for journal subscriptions. They are good partners in this. In fact, they get frustrated by the fact that academics are so uneducated about the issue. It would be interesting to add up how much my university pays for all subscriptions to philosophy journals and books, and then compare that to the cost of subsidizing an OA journal. If each of the top 30 or 50 universities sponsored an OA venue — journal, reference, monograph, what-have-you — we could ditch commercial presses and get it done. The tough thing now is that if a university library tries to sponsor something, they are doing that WHILE ALSO paying for loads of subscriptions. Group action would solve the problem. It’s entirely possible that those 30-50 universities would pay the same or less than they do now, and in the process they’d make the results of all research freely available to all other colleges, universities, students and scholars in the world. Not a bad deal. I think I’ll ask our librarian to ballpark how much we spend on philosophy. If I find out, I’ll get back to you.

Another difficulty with the current subscription-based structure is journal bundling (you can get journal x only if you also pay for journals y and z, which may not be well-read or important to users of the library and so are just a waste of money). I would be interested to see just how precise a figure — such as the cost of philosophy journals — can be for a large academic library. I only ever hear rumblings of total cost per large contract (e.g. cost of doing business with Elsevier across all journals and all disciplines).

Add in the fact that the library doesn’t actually *own* the materials outside the subscription (i.e., unsubscribing means the back-issues go away too), and I wonder how helpful considering cost alone really is. It’s certainly a good question to raise, though.

OUP, among others, have a specific policy for institutions in parts of the world where funds for journal subscription may be minimal:

http://oxfordjournals.org/en/librarians/developing-countries-initiative/index.html

I’m happy that OUP is doing that, though I have to be honest, it’s the same sense in which I’d be happy if Walmart gave their workers a 15 cent an hour raise. It’s better than if they didn’t, but the system is still incredibly flawed and unjust. To take one of dozens of issues here, I have a friend who left grad school, but is considering coming back to finish her PhD. Since she is not enrolled, she has no access to a lot of current work she’s need to have access to to get back into gear. SEP and Philosophers Imprint are freely accessible to everyone on earth, no ifs, ands or buts. No “if you are a college in one of the listed country with no money, apply and maybe we’ll give you (and your registered students) no or reduced fees on “select” OUP journals.” No. SEP and PI are just available to everyone.

Let’s not lose sight of what is happening here: we are working to produce a product, research, that we want to be made as widely available as possible (everyone wants their work to be read), we then sign over copyright of that product to a capitalist commercial entity one of whose main jobs is to limit access to that product through paywalls. If it weren’t so serious it would be a Monty Python sketch.

And for a taste of what they’ll do if you we try to let students learn from our own work without them paying for it (can my eyes roll up any farther in my head??):

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/16/technology/16school.html

Setting to one side the presumption in claiming that I don’t know what it’s like to be in the 99%, the crucial point has been raised – who will cover the costs? Does anyone seriously think it is a feasible option that here in the UK, given the current political and economic climate, universities will band together to support journals like the BJPS? And will the journal and its archives be safe from budget cuts? As a union rep I have seen library resources get slashed, well known and much respected repositories of valuable material sold off, and the associated staff members ‘redeployed’ or pushed into ‘voluntary redundancy’ – what guarantees do we have that that won’t happen to a journal? And what about editorial independence? Again, in the current environment, I’m sceptical … (And again, as a UCU rep I’ve first hand experience of the pressures that can be brought to bear …)

But I agree that more should be done to open up access for colleagues, students and others in developing countries and publishers could provide more support along these lines. Ultimately I think we should have a mixed bag of open access and subscription based journals, but the idea that universities could host them all is unfeasible and actually quite troubling.

Universities are already supporting those costs. Commercial publishers’ income comes from University Libraries’ budgets. The question isn’t; Should Universities start paying to do something that someone else is doing for them for free? It is rather: Should Universities better manage the resources they have in such a way as to remove some social evils and make research and education better for everyone? (And the “going to a computer to see what it’s like to be part of the 99%” was addressed to everyone at large, being part a reply to the main thread and not a reply to your comment. Apologies if it came across as though I was addressing it to you specifically. I’m hopeful that many people in the 99% are reading this discussion. Who is and who isn’t, I don’t know. Except I know that I’m not in the 99%, and a lot of people are.)

Ah, that time honoured manoeuvre of setting up a question that no-one could/should deny …!! My point was that in the current environment (at least here in the UK), it is just not feasible to expect universities to club together and agree to take on and bear the cost of academic journals (and which ones? only those based in the UK??); nor do I think that would be such a good idea – again given the current environment in the UK where universities such as mine increasingly see themselves as businesses, very much willing and able to ‘restructure’ resources such as libraries, research centres and indeed whole schools in order to meet the demands of ‘the market’. But of course, I agree that more needs to be done to support both colleagues and students at institutions in developing countries as well as those outside of the usual academic framework, such as your friend, in order for them to gain access to these resources. What I’d like to see are some practical suggestions along those lines …

Public libraries having the option to subscribe to academic journals at reduced rates would be a step towards making academic research available to those without institutional affiliation. I doubt this would have any discernible impact on journal income (university libraries are unlikely to end their subscriptions because a local library can also subscribe) and it might also help our ailing public libraries.

I have an idea. Create a Consortium for Research Accessibility. People in the 1% who have access to everything are on a widely-distributed email list. If someone in the 99% needs access, we get them what they need. Will Springer sue us for copyright infringement? Bring it. I do your work for free.

Thanks to everyone for their input. I was hoping some leading members of the profession would offer to start/host a petition, boycott, or campaign to put pressure on journal publishers or journal editors. But I guess the appetite is not there, which is a real shame.

There might be tappable momentum for such a thing, but it’s unclear what the suggested direction is. Campaign various journal editorial boards to do what Lingua did? Campaign publishers to reduce prices on journals? These are very different things, even if they have some shared consequences. Mixed ideas have come up, and that will dissipate momentum. I’d support anything to do what Lingua did. But philosophers are very uneducated about OA publishing and as a result they tend to hallucinate downsides that aren’t there, and fail to see upsides that are. And so it might be tough to build consensus for a Lingua-type move in our relatively uniformed discipline. I hope I’m wrong, but that’s my sense of things. I think PI and SEP are starting to change that, which is nice.