“Raw Intellectual Talent” and Academia’s Gender and Race Gaps

Cultural beliefs and stereotypes that associate men but not women with “raw intellectual talent” can help explain the differing gender gaps across various academic disciplines, according to a new study by Sarah-Jane Leslie (Princeton), Andrei Cimpian (Illinois, Urbana-Champaign), Meredith Meyer (Ottterbein), and Edward Freeland (Princeton) published today in Science. A similar account appears to explain racial disparities in academia, as well.

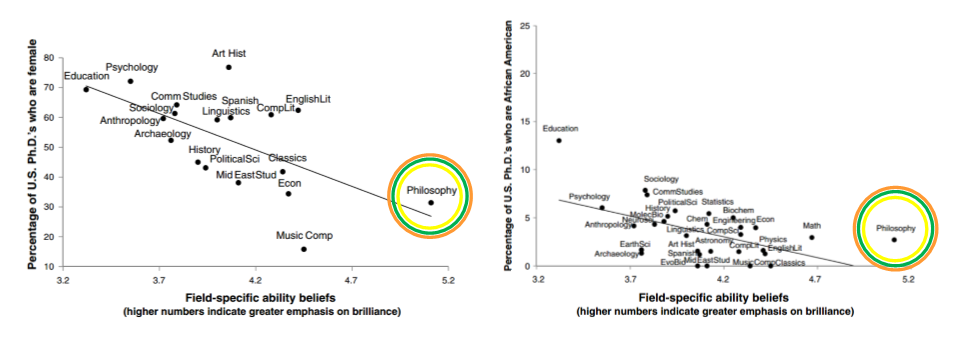

In short, “the more a field valued giftedness, the fewer the female Ph.D.’s” And guess which field values giftedness the most?

The authors begin by noting certain data on gender and academia:

Recently, women have earned approximately half of all Ph.D.’s in molecular biology and neuroscience in the United States, but fewer than 20% of all Ph.D.’s in physics and computer science. The social sciences and humanities (SocSci/Hum) exhibit similar variability. Women are currently earning more than 70% of all Ph.D.’s in art history and psychology, but fewer than 35% of all Ph.D.’s in economics and philosophy. Thus, broadening the scope of inquiry beyond STEM fields might reveal new explanations and solutions for gender gaps.

Their explanation for the pattern of gender gaps—why some disciplines are dominated by one or another gender—is ultimately that, for a number of reasons, disciplines that are thought by their practitioners to require “fixed, innate talent” for success may be inhospitable to women. They write:

Individuals’ beliefs about what is required for success in an activity vary in their emphasis on fixed, innate talent. Similarly, practitioners of different disciplines may vary in the extent to which they believe that success in their discipline requires such talent. Because women are often negatively stereotyped on this dimension, they may find the academic fields that emphasize such talent to be inhospitable. There are several mechanisms by which these field-specific ability beliefs might influence women’s participation. The practitioners of disciplines that emphasize raw aptitude may doubt that women possess this sort of aptitude and may therefore exhibit biases against them. The emphasis on raw aptitude may activate the negative stereotypes in women’s own minds, making them vulnerable to stereotype threat. If women internalize the stereotypes, they may also decide that these fields are not for them. As a result of these processes, women may be less represented in “brilliance-required” fields.

The authors made use of data from a large study of U.S. academia and compared their view, which they refer to as the “field-specific ability beliefs hypothesis,” to others involving longer work hours, gender distribution at the high-end of aptitude, and the extent to which the different fields require systematizing versus empathizing. They report:

Our findings suggest that the field-specific ability beliefs hypothesis, unlike these three competitors, is able to predict women’s representation across all of academia, as well as the representation of other similarly stigmatized groups (e.g., African Americans)…

Like women, African Americans are stereotyped as lacking innate intellectual talent. Thus, field-specific ability belief scores should predict the representation of African Americans across academia. Indeed, African Americans were less well represented in disciplines that believed giftedness was essential for success.

Might it be that natural brilliance is indeed more important in certain disciplines than in others? The authors write:

The data presented here are silent on this question. However, even if a field’s beliefs about the importance of brilliance were to some extent true, they may still discourage participation among members of groups that are currently stereotyped as not having this sort of brilliance. As a result, fields that wished to increase their diversity may nonetheless need to adjust their achievement messages.

Are women and African Americans less likely to have the natural brilliance that some fields believe is required for top-level success? Although some have argued that this is so, our assessment of the literature is that the case has not been made that either group is less likely to possess innate intellectual talent (as opposed to facing stereotype threat, discrimination, and other such obstacles)…

They suggest:

Academics who wish to diversify their fields might want to downplay talk of innate intellectual giftedness and instead highlight the importance of sustained effort for top-level success in their field.

You can see from the charts at the top where philosophy is. More than any other discipline, philosophers place the greatest emphasis on brilliance, or innate, intellectual talent in their assessment of what is required for success in the discipline. Also, philosophy has among the fewest women PhDs (only four other disciplines have fewer—engineering, computer science, physics, and music composition) and a below average number of African-American PhDs.

Related Links:

– Video of Sarah-Jane Leslie discussing these findings.

– Commentary on the study by sociologist Andrew M. Penner (UC Irvine).

– A FAQ sheet for the study.

– The study’s supplementary materials, including further data and information, including the questions asked and individual answers. (Thanks, Kenny.)

UPDATE: Coverage at The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Washington Post, Reuters, and Smithsonian Magazine.

UPDATE 2 (2/4/15): Alison Gopnik discusses the study in the Wall Street Journal.

(image: charts from “Expectations of brilliance underlie gender distributions across academic disciplines” by Sarah-Jane Leslie et al)

It seems really surprising to me that philosophy has this “field-specific ability belief” to a greater degree than math, or music composition. But not only do these surveys show that this sort of attitude is expressed to a greater extent in philosophy than in those other fields, but that there is in fact a dramatic difference.

For people who are interested, the actual questions asked and responses gathered from different disciplines are described in the supplementary material here: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/suppl/2015/01/14/347.6219.262.DC1/1261375.Leslie.SM.pdf

And they posted the individual responses, not just the averages and headlines. That’s great; I wish more work with survey data was presented the same way.

This is really interesting. It might also explain an observed phenomenon: Namely, that it seems in continental circles there is less of a gender gap than there is in analytic circles (I don’t have data on this, and could simply be the particular conferences and universities my friends and I go to).* As someone trained in the continental tradition, while innate brilliance is still a strong idea, there is a high degree of emphasis on doing the work. That is, reading extensively on the topic, learning the languages, perhaps archival work, and finally, the book is privileged over the article. I have seen my analytic friends and colleagues occasionally use the term scholarly as a put down. Which is utterly inconceivable from a continental perspective (calling a work scholarly is always a compliment). This sociological difference might explain why there seems to be more women in continental circles than analytic circles.

* This is intended only to talk about the gender gap between analytic and continental. I am saying nothing here about which field is less sexist, suffers from less sexual harassment, is more likely to include women in syllabuses, or anything of the sort. This is only about a what seems to be different in the gender gap, and an interesting argument for why.

Kenny, I’ve heard many a Math colleague argue that at least in the USA, Math got active and serious about changing the culture of “field-specific ability belief” decades ago, because of the massive federal funding, post-Space-race, to improve achievement in Math. It is Math professors who give me optimism for Philosophy, because they’ve insisted to me often that whenever a field really widely takes on dedication to change, and even just most of its members commit to and engage in better practices, things change for the better. That’s great news! It means there are measures that work and when people implement the measures, they have some success.

(Of course, they also enjoyed monetary investment in making changes. I’m less optimistic that we’d have same.)

Why is it I still fail high school geometry? I must lack some “field-specific ability belief” somewhere or tother.

George DeMarse

Hi Anon, I think it would be best to conclude that your friends have some weird hangups about the word ‘scholarly’. None of what you attribute to analytic philosophy by way of ‘doing the work’ seems familiar to me, except the book vs. article thing. Scholarly seems to me to be a complimentary feature of a work, I don’t think one should publish on an author if one did not read their work in the original language, and everyone should know the literature on a topic before the publish (otherwise what would be the point of publishing?). Further I have never known anyone how managed to complete grad school and get a job who denied those claims. Perhaps I am the one with peculiar friends and colleagues though.

Arrgh. What I meant to say is that I did not know anyone who disagreed with me. It is not relevant whether anyone denies that I feel the way I do. Also I like edit buttons.

That sounds implausible, Patrick. I know a few people who have published work on Kierkegaard although they do not read Danish. Your view that that couldn’t be ok is understandable, but do you really not know anyone who disagrees with it? (I disagree with it.)

This was also featured on NPR today—not fantastic coverage, but here’s the link: http://www.npr.org/blogs/ed/2015/01/15/377517778/do-fictional-geniuses-hold-back-real-women

Observation: the first graph indicates that there are 11 majority-female programs and 7 majority-male.

Question: are people in Art History, Education, and Psychology concerned about their gender climate? Should they be?

I’m a math professor at a small liberal arts college. There is a widespread belief in the field that innate mathematical ability is indispensable, but this has not meant (at least to the many mathematicians that I interacted with) that female possess less of it than males. We had an equal proportion of male and female students finish the PhD program I was in. Also, at my current institution, half of the best students Ive taught (i.e. the ones I think would finish a PhD program in math) were females. In the academic conferences that I’ve attended, there are a far greater number of senior male mathematicians than senior female mathematicians, but among mathematicians under (say) 45, the male-female ratio is closer to 60-40. One of the recipients of the Fields Medal (our Nobel, though given out only every 4 years) was female. From everything I’m reading, the culture in math is quite different from philosophy with respect to gender. But the disciplines are comparable with respect to African Americans. There were no AA students in my program during my time in graduate school, and this certainly wasn’t unique to the program I was in. Math has a very long way to go when it comes to including more African Americans in the field.

Well I suppose that now I do, in some loose sense. It probably has to do with the norms where I went to grad school, and the figures who tend to get worked on. I went to Cornell. Ancient was a huge deal there at the time (and very likely still is), and if you wanted to work on it you had better learn Greek. Everyone I talked to about the issue said that sight reading of Greek texts was part of the exam to proceed on to the dissertation phase. Something similar was, I believe, true of people working on German figures (usually Kant). I think these norms, and how I saw history being done there, probably shaped my opinions and the opinions of people I have talked philosophy with the most on how to do history of philosophy. But I think you raise a good point. When the language is one where the resources to learn it are easily available then I think that my position is the right one. With Kierkegaard I suppose it reasonable to disagree, on account of the difficulty of finding a way to learn Danish. That is offset a bit in the case of Kierkegaard on account of how literary he was. I would worry very much, given all the game playing going on in his texts that if I didn’t read the original I would be missing something vital. But I never knew a grad student who worked on Kierkegaard, and the faculty member I knew who worked on him did know Danish (I believe so anyway on account of her having lived there for a while).

@Kate Lane

“Kenny, I’ve heard many a Math colleague argue that at least in the USA, Math got active and serious about changing the culture of “field-specific ability belief” decades ago”

You’re absolutely right, the problem is that nobody believes it. I remember one of my professor, who was a former child prodigy and part of the John Hopkins program, explaining to prospective graduate students that natural ability didn’t matter for research level mathematics. He was greeted with complete incredulity.

“However, even if a field’s beliefs about the importance of brilliance were to some extent true, they may still discourage participation among members of groups that are currently stereotyped as not having this sort of brilliance. As a result, fields that wished to increase their diversity may nonetheless need to adjust their achievement messages. … Academics who wish to diversify their fields might want to downplay talk of innate intellectual giftedness and instead highlight the importance of sustained effort for top-level success in their field.”

I’m pretty nervous about this. On the natural reading it seems to be saying that we should downplay the importance of innate intellectual giftedness in a given field *even if it isn’t true*. But I actually do think that a successful career in (say) theoretical physics or pure maths research does require a lot of innate talent, and I’m not going to pretend otherwise to my students when giving career advice. (I’m ambivalent about the extent to which that’s true in various bits of philosophy.)

Incidentally (and in re (4) and (12)): if you look at the report then Maths is (after philosophy) the subject that places the highest value on innate talent – so whatever progress Maths has made doesn’t seem to have been via challenging the innate-talent culture. In fact, it’s interesting to see that Maths has a substantially less uneven gender distribution than Physics even while valuing innate talent more.

Can’t it be acceptable to believe that some fields require individuals to have innate talent, without discrediting the idea that some hard-working, intelligent individuals can achieve the same academic feats as those with innate talent?

It looks like the pipeline problem in philosophy is most pronounced at the transition from taking introductory philosophy classes to taking more classes / majoring in Philosophy. (See Paxton, M., Figdor, C., and Tiberius, V. (2012). “Quantifying the Gender Gap: An Empirical Study of the Underrepresentation of Women in Philosophy.” Hypatia, 27(4), 949-957.) So what can we do in our introductory classes to help communicate the message that success in philosophy isn’t mostly a matter of being innately gifted?

I can only talk about the philosophy pipeline over 30 years ago when I took graduate work at SUNY. All I remember is how the faculty kept asking repeatedly “do you really want to this? You know you won’t get a job?” When I replied that I really wanted to understand Aristotle better, they shook their heads in amazement. I finally gave up and became and management major instead.

@AnonMathematician

If this professor really said categorically that “natural ability didn’t matter for research level mathematics” I think that the incredulity is warranted–this seems to be falsified by the overrepresentation of former child prodigies on elite mathematics faculties.

What I think most would agree with is that exceptional natural ability by itself is neither necessary nor sufficient for research level mathematics: even brilliant people need a certain degree of persistence and perspective that often hasn’t been required of them before grad school, and less-than-brilliant people who do show these qualities make plenty of genuinely valuable contributions.

There is a long version of the video as well. http://youtu.be/FM6mbSiD3eA

What the study seems to lack is an explanation on why women “dominate” fields like Psychology, Education, Social Work, etc. Where the gender gap favours women more than the gender gap favours men in Philosophy (otherwise the story seems incomplete, unless you assume is fair that 70% of Psych, etc are women). And it also probably has to do with gender related reasons, like the perception than men have less empathy, are more violent or are less suited as caregivers than women – i.e. as lacking certain kind of talents.

I’m only able to access the supplementary info to the article, but I’m wondering why the authors decided to emphasize the (negative) correlation they found between field-specific ability beliefs and percentage of female PhDs considering that several of the other correlations they found are equally strong or even stronger, e.g. the (positive) correlation between percentage of female PhDs and how “welcoming to women” the field is perceived to be.

Yup, philosophy has been for 2500 years where you try to bring your A Game and see how it matches up the Big Boys’ A Games.

I don’t know about Art History and Education, but I have heard plenty of Psychology profs and grad students talk about the underrepresentation of men in their fields (and especially in certain subfields). And here’s an article about it on the APA website, from a few years back: http://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2011/01/cover-men.aspx

I would think that male/female ratios in undergraduate majors would provide some explanation for male/female PhDs in the same discipline. Unless the Science article controls for this or provides some explanation (e.g., this attitude comes across in undergraduate classes as well), I would rank this article as not very scientific.

Although there are top mathematicians who did not do well in math contests, perhaps because they did not care for that sort of thing, many of those who rank at the top in math contests go on to do very good mathematics.

Women are rare among CountDowners (= top 12) in national MathCounts, among USAMO winners (top 12), and among Putnam fellows (top 5). I don’t think there have ever been any blacks in those groups.

‘Intellectual brilliance’ is really useful for lazy students who miss 9:00am lectures and fail to get assignments in on time. They should avoid subjects requiring long essay answers or projects involving teamwork and neat presentations: the need for hard work is then inescapeable. They need courses with high stress exams with difficult questions where they might be able to show off. This might make up for failing to do all the course work and dozing off in lectures from those they consider their intellectual inferiors. This can be a very high risk strategy. Young males are typically more exposed to high risk behaviour than young females : see road and firearm accident statistics etc. With those who have the statistics, see also the extreme tail of the exam results, showing those who fail miserably : more males than females? None of this should of course dissuade parents from encouraging daughters and sons who lack intellectual confidence, and from steadying down sons and daughters displaying unreasonable overconfidence and arrogance.

While it is true that child prodigies are overrepresented in math faculty, they are not always the greatest mathematicians. Grothendieck said that he never won any competitions as a student. There is at least one prodigy about whom the highest ranking mathematicians have said, “X is very smart, but hasn’t done anything truly great.” Selberg was considered a very powerful mathematician, who nevertheless was not considered the smartest. The overrepresentation of prodigies in mathematics has more to do with the institutionalization of the “mathematical method” in academia (analogous to the insitutionalization of the scientific method), which tends to be a winner-take-all game. At some point the losers, among the some very fine mathematicians, decide to stop compounding their losses. It is rational in a winner-take-all situation not to support the winners (e.g., by staying in their programs, adjuncting, finding work in less than ideal locations, providing departmental service and technical support, donating to their institutions, etc), and to do something else.

Plurals never need apostrophes. Never!

In response to Tim O’Keefe’s question: “what can we do in our introductory classes to help communicate the message that success in philosophy isn’t mostly a matter of being innately gifted?”

Some basic thoughts, none tested, just based on my own experience as both a philosophy undergrad, grad, and instructor: to start off with, professors should abstain from referring to famous philosophers as geniuses They should instead say these people had incredible arguments or interesting theses.

Professors should also abstain from saying that ‘some people just get philosophy and some don’t.’ It might seem incredible that anyone would say say such a thing to a room full of undergrads, but I *heard this said many times as an undergrad* by multiple philosophy faculty, all of whom were extremely well-intentioned and in many other ways excellent teachers and mentors.

In my own teaching of philosophy, I have frequently emphasized explicitly how much work it is (this was before I had the benefit of Leslie’s research, of course, but I disliked how much my own undergrad profs emphasized brilliance and have deliberately tried to give my own students a different sense of how philosophy is done). When papers are coming up, I say out loud ‘Writing philosophy papers is hard. Be patient with yourself. Do multiple drafts.’ I’ve also explicitly mentioned that in my own work, I frequently work on ideas for a long time, only to decide I need to move in a different direction, or work on a paper for a long time, only to decide I need to re-draft it completely.

Finally, I there appears to be a deep discipline-wide issue here, as Leslie’s work indicates. And I think we’ve all seen it. At least, in my own life as a philosopher, I’ve on many occasions witnessed philosophers sitting around, drinking beers, making lists of who is ‘good’ or ‘not good’ in the discipline. They can entertain themselves with this who is ‘good’/’not good’ game for a shockingly long time. I’ve always found it bizarre and, from discussing it with my academic friends in other disciplines, it appears to be something of a philosophy-specific practice. A simple suggestion about how to counter this: by all means, *do* say, ‘I like their work on X’ or ‘they gave a talk on Y that was good’ but don’t just declare them ‘good’ or ‘not good.’ I suspect that in some cases, the reason people don’t refer more specifically to good *work* these philosophers have done is that *they haven’t even read their work.* All the more reason to abstain from the silly ‘good’/’not good’ game.

The study certainly shows that the extent to which innate talent is believed to be required for success in a field is correlated with the size of its gender gap. But moving to the explanatory or causal claim that the “field-specific ability belief” explains or causes the gender gap seems unwarranted. Here’s an alternative potential explanation that seems equally supported by the data presented: (i) the extent to which innate talent is believed to be required for success in a field is a pretty good indicator of the extent to which innate talent is actually required for success, and (ii) innate talent is not evenly distributed across genders (e.g. as in the greater-male-variance hypothesis that is partly responsible for Larry Summers’ notoriety).

The authors try to show that their preferred explanation is superior by introducing a “selectivity” measure and then showing that the correlation between selectivity and the gender gap is less strong than the correlation between field-specific ability beliefs and the gender gap. However, this result only favours the authors’ preferred explanation if their selectivity measure is a reliable indicator of the extent to which brilliance is required for success. But the authors’ selectivity measure is simply the (estimated) percentage of applicants admitted into graduate programs, and it is not at all obvious that this is a remotely reliable indicator of whether brilliance is required. Surely the percentage of applicants admitted depends on a whole bunch of factors that have nothing to do with to what degree innate talent is necessary for success in the field — perceived ease of admissions policies, number of academic jobs in the field, non-academic employment prospects, to mention just a few.

anon grad student: as for the hypothesis that ‘innate talent is not evenly distributed across genders,’ Leslie explicitly addressed that hypothesis in a talk I saw her give on this work (I don’t know if she mentions it in the study). The problem with that data is a strong historical trend showing that in just the past few decades of testing, women’s representation in the very highest ends of intelligence tests have gone up dramatically. Since it’s incredibly implausible that women’s innate ability has actually gone up that dramatically in what is evolutionarily speaking, the blink of an eye, the best hypothesis is that representation at that end has much to do with social, economic, race, and other factors, and not innate ability.

incidentally, i see this hypothesis all over the place on blogs and such: men are overrepresented in the genius area of the bell curve, etc. Even *supposing* that to reflect an innate talent, what in the world is that to do with philosophy? Are we actually thinking that most or even many working philosophers of *any* gender are in that ‘genius’ place of that curve? What a very bizarre presumption (I’m here supposing, for the sake of argument, against what I don’t believe, that these tests are indicative of anything very deep or interesting). Philosophers are all super bright, sure, but *mostly* in the *very* highest echelons of the curve? Color me very, very skeptical. Further, we would have to be positing that philosophers are *more* likely to be in the high-end of the curve than mathematicians, academic lawyers, theoretical biologists, neuroscientists, chemists, artists, novelists, composers, architects, engineers, or nearly any other interesting field where we don’t find the same degree of gender disparity. i don’t buy it.

“incidentally, i see this hypothesis all over the place on blogs and such: men are overrepresented in the genius area of the bell curve, etc. Even *supposing* that to reflect an innate talent, what in the world is that to do with philosophy. Are we actually thinking that most or even many working philosophers of *any* gender are in that ‘genius’ place of that curve?”

Well, yeah, pretty much. Calling it the “genius” area of the curve is highly misleading: if the variance hypothesis is right, then you’ll start seeing significant differences even 2 standard deviations above the mean (with IQ, for instance, that corresponds to something like 130 IQ — hardly genius-level). It seems highly, highly plausible to me that most professional philosophers are at least 2 standard deviations above the mean, and probably more.

Just to briefly substantiate that: it’s well known that philosophy graduate students on average score very highly on the GRE compared to other disciplines. Here, for instance, is some data suggesting that the average applicant to graduate school in philosophy has around a 130 IQ: http://www.randalolson.com/2014/06/25/average-iq-of-students-by-college-major-and-gender-ratio/. I don’t know how good that data is, but it wouldn’t surprise me if it were roughly accurate. And of course there’s reason to think that top professors are going to be even further to the right of the curve than the average applicant to graduate school.

Anyway, the point of my original post wasn’t so much to defend the variance hypothesis as to just point out that as far as I can tell, the Leslie et al study does virtually nothing to favour the perceived-necessity-of-innate-talent-drives-out-women hypothesis over it, and hence the way the study is described seems very misleading. Perhaps indeed other work of Leslie is relevant; but I’d like to see that work.

Two things come immediately to mind. First, couldn’t lack of interest in a field be playing a larger role here than, say, someone’s being “kept out” of a PhD program due to the professors holding some sinister notion of innate intellectual brilliance? Philosophy isn’t taught in K-through-12, for example, and so the first time students come into contact with a professor of philosophy is as an undergrad. It may be that students, especially those who are practical minded and are looking at degrees that will translate into “jobs,” never develop a real interest in philosophy — certainly not enough to invest eight more years in a PhD program. The sort of professor (and this sort of program) that the researchers here assume (in their explanation of the data) can be found in silly fictional accounts, like in _Good Will Hunting_, but are professors REALLY on the look out for their Will Hunting? Really? This is the stereotype in play, I think. Secondly, and this is probably more to the point, couldn’t the over-reliance on GREs be playing a larger role here than, again say, someone’s being “kept out” because professors hold some sort of sinister (and indefinable) notion of innate intellectual brilliance? GREs, in my opinion, are given far too much weight in deciding who to admit to graduate programs, and they certainly don’t seem to predict success in grad school, but administrators tend to okay funding for students who score high on them. Philosophy undergrads who take the GREs and LSATs, for example, score among the highest (in terms of majors), along with physics and engineering undergrads who also take these tests. Perhaps the explanation is in part here? For, these are the very majors of concern, no? Perhaps the over-reliance on GREs (by admission committees) is skewing admissions in the way described in this report.

Interestingly, from briefly perusing the supplementary document, it seems that Leslie et al considered something very much like GRE scores as an alternative measure of selectivity (i.e. as opposed to the primary measure used, which was reported percentage of graduate applicants admitted):

As an additional measure of selectivity, we obtained information on the average GRE scores for 2011‐2012 PhD applicants, which were available for only 19 of our disciplines (20). To create a composite score, we calculated standardized scores for each of the fields on the verbal, quantitative, and analytical writing portions. These three standardized scores were then averaged to produce a composite measure of GRE scores for the applicant pools of each of these disciplines. (p3 of the document).

But although they say that this measure is considered, I can’t see anywhere in the document where the results are reported. (On p11, which contains the table showing the main correlations, only the original selectivity measure is displayed). I’d love to know if I’m missing something. (IMO, at least, the alternative measure seems like a much better measure of selectivity than the primary measure, so it’d be interesting to see how well it correlates with the gender gap).

justin’s usually pretty good about moderating this blog. but there are still ‘bell curve’ bros all over this thread. I don’t think we should have to sift through this shit just to get our daily nous.

justin, are you taking the day off?

Complaining to the moderator about the appearance of “‘bell curve bros'” sounds like “more echo-chamber please.”

What’s the complaint, anon? I’m not following the “bell curve bros” remark. Sorry.

From what I gather (and someone please correct me if I’m wrong), the explanation of the data on the table is that professors in certain disciplines (I’m in philosophy so I an really only speak to that) have some sort of archaic, racist, sexist belief about innate intelligence or about something being called “intellectual brilliance” (whatever that is). And, it’s that archaic, racist, sexist belief that drives a palpable disparity with respect to racial, ethnic, and gender features of PhD-holders in various disciplines. My suggestion was simple (simple-minded?): perhaps the disparity has to do with student interests and the selection process over-valuing things like GRE test scores. anon (grad student) considers a jumble of IQ measures, but such things, as far as I’m aware, are never part of a student’s application to grad school. I’m willing to accept the study’s explanation (after considering the alternatives), but at the moment I find it too…well…fantastical. To be sure, some professors may hold such beliefs, but could you name even one? I can’t. But even if you could find one or two or three in a single department, those individuals will not be able to control the entire admission of grad students into a program, let alone the entire discipline. So, either lots and lots of professor hold the belief and never show it in contexts outside of admissions, or hold the belief but unbeknownst to themselves. I find either of these difficult to buy. Anyway, I’m thinking that there is a better explanation than the one proposed in the study.

“To be sure, some professors may hold such beliefs, but could you name even one? I can’t.”

But of course these beliefs aren’t generally explicitly, consciously held. As the past 2-3 decades of social psych research on sexist/racist cognition has taught us, they’re non-conscious biases–non-conscious attitudes utterly at odds with what their subject endorses. A classic paradigm in this area is the resume paradigm where an identical (fictional) resume is distributed to two groups. In one, subjects are told the resume belongs to a woman. In the other, subjects are told the resume belongs to a man. Subjects in the first group rate the ‘woman’ as less capable in several respects than subjects in the second group rate the ‘man.’ And these are subjects who are explicitly, apparently sincerely, anti-sexist. But their actions are sexist nonetheless.

The implicit bias literature *is* truly ‘fantastical’ — at least I found it so when I first encountered it. Because it shows that most of us are non-consciously racist and sexist in a way that is at odds with our avowed beliefs. The results are also undeniable (there is now a mountain of literature on implicit bias, including many that test bias in the real world). The fantastical is, at least in this case, how the world actually is.

Regarding Kurt on “student interest”: I must say I am suspicious of explanations of gender disparity in philosophy (and related fields) that say that women are under-represented in philosophy because they are less likely to be interested in philosophy than men are. Interest is not just a given. You’re more likely to be interested in fields that you feel like you have a good chance of being successful at, that you’re encouraged to pursue, that you feel that you can make a contribution in. Perhaps women are less likely to be interested in philosophy, but then I think we should ask why, and the answer might well be something like the hypothesis of Leslie et al. (You might ask: is it a bad thing if women are less likely than men to be interested in philosophy, hence go into the field in fewer numbers? Answer: Yes, if the relative lack of interest is due to e.g. false perceptions of women’s capacities to succeed as philosophers.)

RE: “From what I gather (and someone please correct me if I’m wrong), the explanation of the data on the table is that professors in certain disciplines (I’m in philosophy so I an really only speak to that) have some sort of archaic, racist, sexist belief about innate intelligence or about something being called “intellectual brilliance” (whatever that is).”

That is not *the* explanation on the table. The belief that it takes innate talent to succeed in philosophy need not be held by professors. Indeed, that’s just one of the hypotheses floated by Leslie et. al. Here’s a quote from the third paragraph of the article: “The practitioners of disciplines that emphasize raw aptitude may doubt that women possess this sort of aptitude and may therefore exhibit biases against them (10). The emphasis on raw aptitude may activate the negative stereotypes in women’s own minds, making them vulnerable to stereotype threat (11). If women internalize the stereotypes, they may also decide that these fields are not for them (12). As a result of these processes, women may be less represented in “brilliance-required” fields.”

Two of the three hypotheses floated have nothing whatsoever to do with practitioners’ beliefs. If the belief that innate talent is required for success in philosophy is widespread among *applicants* who also tend to believe that they lack such talent, that would help to explain the gender disparities across disciplines.

For my part, I find this far more plausible than the hypothesis that it is primarily the practitioners of the fields, and in particular, their FABs, that are most to blame. I find that hypothesis harder to believe because women tend be less interested in studying philosophy before they even arrive at college—that is, before they have ever met a professional philosopher.

It is true that intro courses tend to be more gender balanced than upper-level courses, but this is not fatal for the hypothesis that many of the causes of the gender disparity in our field are in place long before students reach college. If the initial disparities found in intro courses are explained by pre-college field-ability beliefs, we should *expect* those same beliefs to continue chipping away at women’s inclination to study philosophy, progressively causing more women to dropout without any need for further discrimination by practitioners.

Of course none of this is say that discrimination from college professors doesn’t contribute *at all* to explaining the disparities, much less that we couldn’t do a lot more to actively correct such beliefs in our students! (Although, in response to Anon Prof 3:53, I do think there might be some reason to ask whether we ought to: increasing the number of women in philosophy will mean decreasing the number of women in (e.g.) psychology, and I’m not sure I could recommend to any arbitrary female student that she should study philosophy rather than psychology!) But I do think it’s worth remembering that many of the causes of gender disparities in academia plausibly lie in stereotypes that are widespread in society more generally. The many studies of differences in how adults interact with infant boys and girls — for e.g., the number of words spoken to babies varies greatly with gender — are just one example of how early these processes begin. We should not underestimate their power to influence decisions, even once the kids have moved to college.

Thanks to those who replied to my comment.

I don’t see how what Anon G5 says is really all that different from what I say, though I take it that Anon G5 intended it to be a response to what I said. Perhaps it’s this: I say that students are much more practical minded and informed than the study’s explanation grants. By “interest” I mean practical interests. I don’t mean anything like “inherent” interest. If a student is the first in his or her family to go to college, and he or she is convinced that the aim of the college degree is principally a set up for a career, then lots of majors, no matter how interesting they may be, will be low on the list–that is, if the student doesn’t see any practical future (read here “career”) payoff in majoring in those disciplines. I mentioned that fact that philosophy is not taught in k-through-12. That has a real impact on how students assess its value when they get to college. They may take an introductory course, absolutely love it, but for the practical concerns just mentioned, determine that it’s simply not worth pursuing (especially at the PhD level!). Appealing to some mysterious deep seated (unconscious) belief about innate talent being required by a discipline seems a far stretch. I agree that much of the baggage that may account for someone’s choice of major (or even whether to go college) is in place long before students step foot in a college classroom.

So, is this discussion about the “message” expressed by the baggage? That is, students will have baggage no matter what, since that is basic human nature, so what needs fixing is the message expressed by the baggage. Ideally, the baggage should be express a more positive message. Or, is this discussion about their being baggage–period– whether positive or negative? If the former, then who gets to say what the message ought to be? That, it seems to me, goes way beyond social psych research (as asdf referred to it). So, you don’t like this or that stereotype. What about the stereotype that doesn’t like this or that stereotype? Determining which stereotypes people “ought” or “ought not” to have sounds dangerously political to me. At least, this is something that isn’t “scientific”. If the latter, then is the problem with human nature? We simply don’t want students to come to college with any biases? Isn’t this simply a bias against biases? Ugh!

I wonder if there is anything to make of the fact that the “field-specific ability beliefs” are taken wholly from academics, and largely from very new-to-the-field academics, as grad students dominated the pool. In many fields, many Ph.D.-level professionals are working in private or government labs, for example. It’s obviously easier to gather subjects by tapping university webpages, but I think it would be worthwhile to cast a wider net. People employed (or contemplating being employed) outside of academia may have different views on the questions being asked.

I might add, and this will be my last, that the study and many of the participants in this thread seem to assume that the distribution of sex, gender, race, and ethnicity within academic disciplines ought to reflect that found in society (understood large-scale). Without this assumption, there really is no “problem”. But why think that such subgroups (like academic disciplines) ought to express such ratios? I’m not saying that they shouldn’t, but what reasons do we have for thinking that they should? I think that the view that we should expect subgroups to express the same sex, gender, race, ethnicity ratios as found in the larger society (the largest social group) assumes what we might call a “fractal” view of society. The identical proportion (of sex, race, etc.) must be found at every level, in every definable subgroup. That, it seems to me, is not a realistic view (though it may be ideal). As Aristotle noted, the various subgroup “levels” really are different: family structure is different from village structure, which is in turn different from city-state structure.

For my part, I think that the concern over this area of diversity (sex, gender, race, ethnicity), though important for lots of reasons, is nevertheless misplaced when considering the topic of academic diversity. The sort of diversity that philosophy as a discipline ought to concern itself with will be understood in terms of different approaches and different areas of study. So, the discipline is diverse in the sense that it endorses various approaches (the dreaded analytic/continental distinction might come in here), and the exploration of different areas of study, such as metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, logic, philosophy of religion, philosophy of science, feminist philosophy, ancient philosophy, modern philosophy, existentialism, phenomenology, political philosophy, etc.

Take out education from the right hand chart and you lose any significant correlation… not a very convincing analysis.

I have read much of Leslie’s work, both in philosophy and psychology, and have always found it to be extremely engaging, novel, and sophisticated. This study is up there with all of it, and of course the topic is very important for the discipline as a whole. Professor Leslie, we all owe you a debt here, so thank you.

Two (somewhat related) points:

(1) At the stage of encouraging people to take more philosophy classes after Intro and to consider majoring, I think that David Wallace’s worry above is moot. Leaving aside issues of “raw intellectual talent vs. hard work and good habits” for success as a philosophy academic, I see nothing problematic in telling beginning undergraduates, either explicitly or implicitly, “Philosophy is a really difficult subject, and it’s a lot different from most of the things you’ve studied before. But if you put in the time to do the readings carefully and prepare for the exams, get feedback on drafts of your papers, and ask questions whenever you’re not sure what’s going on, you’ll be able to learn how to do philosophy.”

(2) At the stage of advising people whether or not to apply to PhD programs–after giving all of warnings that we ought to about the job market–I think we’re better off being guided primarily by the students’ actual record of accomplishment in their classes rather than by our impression of how “smart” or “brilliant” they are. People should read Eric Schwitzgebel’s on being good at seeming smart for the dangers of relying on our impressions of brilliance rather than actual accomplishment.

The hypothesis tested by Leslie et al involves TWO assumptions that go together to produce a lower % of women in a given field. The first assumption is that the field requires certain levels of innate ability or talent. Commentators focused just on whether philosophy, or math or physics, require innate taken are missing the point. It is totally compatible with their conclusions, or any other conclusion, that philosophy does (or doesn’t; I am skeptical, personally, of anyone claiming that they can’t name even a single prof who believes that philosophy require innate talent).

The second assumption is that women are less likely to have that innate talent. And there is loads of good research showing that pretty much all of us do a poor job assessing the “raw brilliance” of male versus female students or colleagues. This need not be an explicitly endorsed belief; it merely needs to show up in the statistical way in which people assess the talents of various demographics of students or peers.

Believing that philosophy requires some measure of innate talent is not itself problematic. But, it is deeply problematic when it is combined with an environment where what we are most liable to mis-judge is the innate talent of male vs female philosophers. The “pure brilliance” assessment is one of the kinds of judgements most likely to be affected by implicit bias, and so is most likely to affect gender distributions in fields where there is also the belief that pure talent is crucial.

Their research also fits in with the analyses of adjectives used to describe job candidates in letters, for instance; women get a significantly higher % of the “hard worker, studious,” etc. adjectives, and men get a higher % of “brilliant, smart” etc. adjectives. In fields where raw ability is considered an asset, those adjectival differences will make a real difference.

I think that at all stages (including hiring) we’d do better to rely on evidence of accomplishment rather than hazy impressions of raw talent. (This is consistent with relying on qualitative assessments of writing samples, although it would be nice to have an easy way to have samples analyzed behind a veil of ignorance so that the evaluators have no information about the applicants’ gender, race, academic pedigree, or letter writers’ identity, only reuniting the assessment with its particular writer afterwards.) To whatever extent that “raw talent” really does play into philosophical accomplishments, let it be factored in via what the person has accomplished, rather than via trying to assess it directly (which will be unreliable and biased).

Scott Alexander has a lengthy but extremely interesting rebuttal to the Leslie et al paper here: http://slatestarcodex.com/2015/01/24/perceptions-of-required-ability-act-as-a-proxy-for-actual-required-ability-in-explaining-the-gender-gap/

Headline points: The “innate ability is actually required” hypothesis is a lot stronger than Leslie et al suggest. Once you disaggregate the various components of the GRE, and focus specifically on the quantitative score, there’s a huge correlation (r = -0.82 ,p = 0.0003) with gender representation — indeed a much stronger correlation than Leslie et al’s correlation with perceived innate ability.

There’s a ton more there.

Noone who actually has read Leslie et al.’s study need read further than the analogy in the fourth paragraph of Alexander’s rebuttal, mentioned above.

tl;dr Leslie et al.’s study is just fundamentally flawed. They pretend to find a causal relation between perception of innate ability and gender representation, but the causal relation is obvs between actual innate ability in field X and gender representation. We can show this by discovering a surprising strong correlation between qualitative, i.e., math GRE scores (a proxy for innate ability to succeed in any field!) and gender representation. And qualitative reasoning is a kind of innate ability that can’t be taught, and men just are better at it. We know this because men do better at math in both the GRE and the SAT, so it’s not just because they tend to take more math in undergrad.

Mr. Zach’s analysis, I think, begs the question (at least this would be what the authors of the study might say). He says that men have better innate reasoning abilities than women, and bases this on the results of the GRE. The authors of the study don’t deny this sort of thing. Rather, they are trying to explain why the GRE results are as they are, their main thesis being that women perform more poorly on the math section because of certain stereotypes they have. (Btw, Mr. Zach, although you refer to a ‘qualitative’ section, identifying it as the math section, it’s the quantitative section, no?) Mr. Zach’s analysis assumes that there IS a correlation between GRE math performance and innate ability. I think that that assumption needs to be challenged. If the “evidence” that GRE scores predict success in grad school is simply that those with high GRE scores succeed, then there’s trouble. For, if those with moderate to low GRE scores are passed over in the acceptance process, and preference is given to those with high GRE scores, then it should be no surprise that those with high GRE scores succeed in grad programs, and those with moderate to low scores don’t. The success would be trivial. I’d be willing to bet that put side-by-side, we would see that those with moderate GRE scores, for example, succeed at least in equal proportion in grad programs (when accepted) to those with high GRE scores. Doing well on the GREs shows basically that one does well on such tests. I’m not convinced that doing well shows anything at all concerning success in a grad program, let alone “innate ability.”

That was my summary of the argument in the post, not a summary of my own view, obvs. Sorry that I didn’t make this clear.

…and I agree with Kurt’s assessment of that argument (again, not mine, and not one I endorse). Also, yes, read “quantitative” for “qualitative”.

Got it! Thanks for the clarification!

In my opinion, people who want to defend the Leslie et al study would be best served by actually making arguments to that effect, as opposed to relying on sarcastic (and IMO tendentious and inaccurate) characterizations of the criticisms.

FYI, if you include GRE math in a regression analysis with the ability beliefs measure, the ability belief’s measure remains significant even though Math gre scores also correlate with the distribution of women across academic disciplines. So you shouldn’t assume just because math GRE is strongly correlated with the distribution of women across academic disciplines that it explains everything. More variance is accounted for by including both regressors.

As I read the supplementary documents on the paper, the sample for philosophy looked pretty non-random, and this would explain why it is such an outlier. They sampled from 9 prestigious research institutions, 5 of them private (these are not named, but they are presumably of the stature of Princeton or Berkeley). In philosophy from these 9 institutions, they got 58 respondents. Of the total, 28 of these were male graduate students, 9 were female graduate students, and the remaining 21 either post-docs or faculty. I doubt that a sample like this is representative of the field. This doesn’t mean the rest of the data is flawed or that the study as a whole is flawed. It just means it would be premature to say the least to conclude that many in philosophy hold FAB beliefs. I’m not even sure male graduate students overall (i.e. not just those in prestigious research institutions) hold this.

Why are almost half of the disciplines missing from the graph on the left ?