A History of Philosophy Journals Using Topic Modeling (guest post by Brian Weatherson)

When you go looking for patterns in over 32,000 academic philosophy articles, what will you learn?

In the following guest post*, Brian Weatherson, Marshall M. Weinberg Professor of Philosophy at the University of Michigan, describes how he applied topic modeling to articles published in philosophy journals between 1876 and 2013 and shares some of his findings.

A History of Philosophy Journals Using Topic Modeling

by Brian Weatherson

Last year, Daily Nous published a discussion of a paper by Christophe Malaterre, Jean-François Chartier, and Davide Pulizzotto using topic modeling to analyse the trends in Philosophy of Science. I thought it would be a fun idea to extend this to other journals, and see if the same techniques could let us see what trends there were in philosophy journals in general. The project got a bit bigger than I expected, and I just finished a book manuscript writing up the results: A History of Philosophy Journals, Vol 1: Evidence from Topic Modeling, 1876-2013.

The model that drives the book starts with the text of over 32,000 articles and looks for patterns within them. I then looked at how those patterns relate to when the articles were published to see what kinds of trends were visible.

The model sorts the articles into 90 topics. I sorted those topics by the average publication date of articles in them, and gave them names, to produce this graphic of the overall trends. (You may need to click ▶ to run the graphic.)

A history of English language philosophy journals in 90 topics in 5 minutes. pic.twitter.com/dUdHnbuE39

— Brian Weatherson (@bweatherson) May 13, 2020

When you start with this many articles there are a lot of fun little things you find along the way.

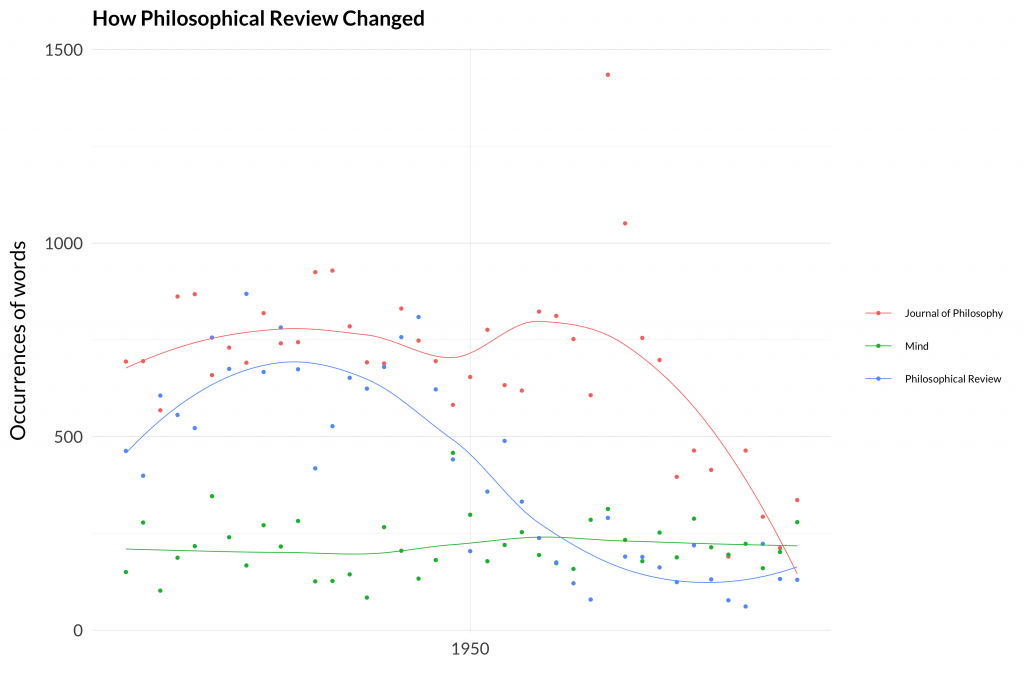

- As Joel Katzav and Krist Vaesen had observed, there is a dramatic change in Philosophical Review around the middle of the 20th century. This trend is visible just in the word counts for key words associated with philosophy of mind, speculative philosophy and political philosophy.

Sum of word usage for 24 distinctive words in the three big journals, 1930-1970

- Philosophy journals publish much less history than they used to, especially about figures outside the canon. The only exception is that work on Hume has increased over time, as he was turned into a central figure in the canon.

- Rawls was so widely discussed in the 1970s that in some years the word ‘Rawls’ is used on average every 2-3 pages across all the journals I’m looking at.

- The only pre-WWII article that looks like contemporary epistemology was published by Dhirendra Mohan Datta, who was trained and was working in Bengal.

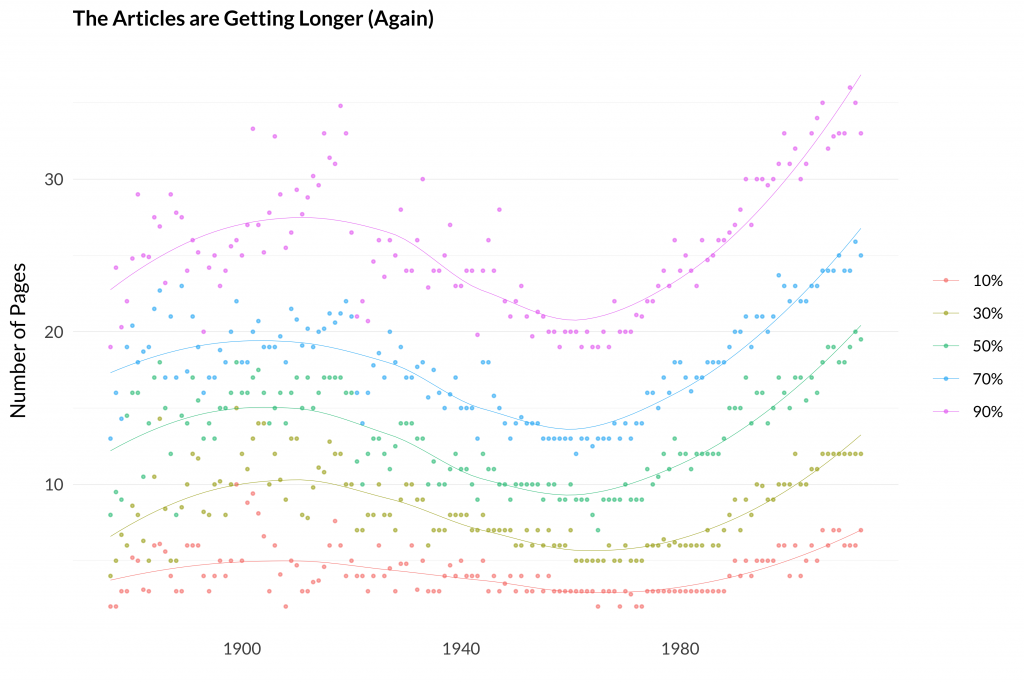

- Philosophy articles are getting much longer than they have ever been.

Graph of deciles of article length over time. It shows a rise through 1910, then a fall until about 1960, then a steep rise through the present.

- There are striking differences between British and American journals. Most surprisingly to me, there is a very long term trend of leading British journals publishing much more philosophy of language than leading American journals.

- 21st century philosophy has a very distinctive idiolect; almost as distinct as the idiolect of ordinary langage philosophy.

As well as all the fun little things, there are three big take home lessons from the data.

The biggest is that there is a huge difference between the work that contemporary analytic philosophers take seriously from the late 19th/early 20th century and the work that typically appears in the journals in those years. There is virtually no discussion of “On Denoting” between 1915 and 1941. Moore, despite his institutional importance, is not prominently discussed in the journals. Frege is mostly invisible until quite late in the 20th century. Wittgenstein’s later work does get picked up by his contemporaries, not least because his students founded Analysis, but the Tractatus is also invisible. The journals (at least the ones I’m looking at) only really start discussing positivism when we’re into the “one patch per puncture” stage of trying to rescue the verification principle.

Instead of discussions of the views we would later associate with the period, the journals in the early part of the century are full of articles on various forms of idealism. The focus is primarily on mind and metaphysics in the British journals, and ethics and political philosophy in the American journals. Just like the prominent authors now are mostly invisible then, many prominent authors of that era are more or less completely forgotten. Shadworth Hodgson published three dozen papers in leading journals, and is rarely even mentioned in passing these days.

Second, epistemology as we understand it is a really contemporary development. In most fields of contemporary philosophy, you can see some precursors in the early journals.

Trends in philosophical categories in the journals.

Philosophy of language is a partial exception; until Wittgenstein’s later work it is a minor presence. But the biggest exception is epistemology. It’s just invisible through the late 1950s. And then even through the 1970s and even the 1980s it is not that big a field, with the Gettier problem being maybe a fifth of all epistemology over that time period. But since the 1990s a bunch of topics (e.g., testimony, disagreement, probability and self-location, norms of assertion, accuracy) have exploded, and it’s become a central part of the story of philosophy.

The third lesson takes a bit of setting up.

I assume that everyone knows that there was a sea-change in philosophy between about 1968 and 1975. A quick glance at article citation rates, or introductory readers, or graduate syllabi, will confirm that. But I think a lot of people conceptualise the change in this period as being centered around mind and language, perhaps extending into metaphysics. It’s Lewis, Stalnaker, Kripke, Putnam, Kaplan, Montague and Fodor who are the central players in this version of the story. And they all are really important figures.

But looking through all the journals of the time what pops out is that there is a change going on in moral and political philosophy at the exact same time that is at least as momentous. The key figures in this part of the story are Frankfurt, Thomson, Rawls, Singer and Foot. Indeed, it seems to be the rising importance of Ethics through the post-war period that really sets up this momentous period. I don’t mean to suggest that people will be shocked to learn that Frankfurt and Thomson were important philosophical figures; but I’m not sure they’re typically treated as being as central to the graduate curriculum as Kripke, Lewis and Putnam. And I think that’s a mistake; they are just as important to the period that sets the agenda for philosophy through at least the 2010s.

As I noted at the start, I’m not the first to approach the history of philosophy journals this way. But this is a new field. And to help anyone else who would like to do something similar, or who (quite reasonably) thinks that they could do a better job than I did, I included a few resources. There is a brief tutorial on how do get started on this kind of analysis. I go into a lot of detail over two chapters about the many choices I made in getting to an analysis, and why there were a lot of reasonable ways to go at a lot of these choice points. And the code for the book is available on GitHub. The book was built using bookdown, which is an incredible piece of software, and I encourage other philosophers to think about using it as well.

If you have any questions about this, or have ideas for other analyses to run on this data set, let me know in the comments.

I am finding the lessons laid out here really fascinating, suggesting the way the history of our discipline has been written right before our eyes. I had had some inkling that the Frege-Russell-Wittgenstein picture of Early Analytic isn’t really accurate to the period because I have been burrowing around in the same journals looking for women philosophers but this material raises lots of questions about how history develops and how some figures get erased.

This is fascinating. Thanks for doing it!

Agreed!

Very interesting. I skimmed the introduction and noticed that Erkenntnis was not one of the journals tracked. I suspect that may account, in part, for some of the surprising data about epistemology and (neo)positivism.

Yes – doesn’t the “protocol sentences” debate take place in the pages of Erkenntnis in the 20s? Maybe that’s not too much like contemporary epistemology, but it’s surely epistemology, and is at least all background to debates about foundationalism, the given, etc. that would play about between Sellers, Chisholm, etc. (And before that, a lot of this is in books by Russell in the teens – _Our Knowledge of the Empirical World_, _Problems of Philosophy_, etc. So, it seems odd to suggest that epistemology wasn’t an important issue in early analytic philosophy.

That’s a good thought – I should really see how Erkenntnis looks in light of the model. It’s true you’d expect positivism to turn up there more than in, say, the Aristotelian Society.

I do look at what the model thinks of those Russell books in chapter 9 of the book. The model isn’t completely convinced that they should go with contemporary epistemology – which disappointed me a little. But they are useful test cases nonetheless. The model thinks that most years there are 0-1 articles across all the journals that are more like contemporary epistemology than the epistemology chapters of _Problems of Philosophy_. Had Russell published those chapters in Mind or Phil Review, they wouldn’t have been outliers in the sense of being completely unlike anything else being published. But they would have been extremely atypical.

And that’s what really surprised me. I thought Russell’s role in the 1910s and 1920s would have been like Lewis’s in the late 20th century or Williamson in the early 21st. They publish a lot, but they also set the terms of debates around which others (including especially their own students) organise. Whether it’s for institutional reasons, intellectual reasons, or just because I’m looking in the wrong places, Russell just doesn’t seem to have that kind of influence.

In _The Logical Syntax of Language_ (published in 1934) there are dozens of citations to Russel, including _Our Knowledge of the External World_ and _An Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy_ (which has the best presentation of the theory of descriptions, I think), more than a dozen to Frege, and several dozen to Wittgenstein, which suggests that a lot of interest in these figures earlier than seems to be showing up here, but in different places (and published in German, at first.)

Schlick discusses Russell, Frege, and Wittgenstein in “The Turning Point in Philosophy”, which was in Erkenntnis (in German) in 1930, and the argument in _on denoting_ (though not actually naming it, though citing Russell generally, in “Positivism and Realism” which was also in Erkenntnis in 1932.

There are a number of other examples from the papers republished in Ayer’s volume on logical positivism, mostly from Erkenntnis and other journals like that. Those same articles also have a lot of discussion of Frege and Wittgenstein in the 20s and 30s.

Ayer himself spends several pages on the theory of definite descriptions in _Language, Truth, and Logic_, and on Russell’s epistemology in the (later) _The Problem of Knowledge_. So, I suspect that things are being left out because of the nature of the search, and that interest in these topics pick up in the US when Carnap and others influenced by the Positivists come and become established a bit later, but this is just their bringing their already existing interest in these topics to new lands. In “analytic philosophy” (i.e., what the positivists were doing in the 20s and 30s) there was already a lot of interests in these figures and topics before they became common in the US (and UK), it seems.

Wow! So much here. Thanks for this fascinating work!

Thanks! This is super interesting. Having only skimmed your documentation, and being lazy, I am wondering if you might be willing to clarify the principles that generate the 90 categories. In short, here are two things I am struck by: (1) Education is not a category (but Dewey does come up). I would have thought that education or some aspect of it would have figured a fair bit, if Dewey did. (2) Emotions is a keyword but ‘passions’ or ‘sentiment’ is not. These concepts are closely connected, yet substantively different, and the word choice matters. (So James in writing on Descartes conflates passions and emotions to completely misconstrue Descartes, and change the way anyone read _The Passions of the Soul_ for many decades. The point of the first is really a question of how topics get selected as worthy of categorization. The point of the second is that is some cases the way a category is defined — and the keywords associated with it — actually evolve, and so any model would need to actually make a decision about whether to count earlier and later favored terms as of the same category or of different ones.

I apologize for being lazy — the documentation is really quite thorough. Thanks for doing all that work and for creating a powerful data set to analyze!

The methodology actually just created 90 lists of word weights, and associated weights on all the articles in the database. After generating these lists, and doing various tests to verify that the model was doing things that made sense, Brian then went in by hand and gave names to these lists.

Notably, he did this entire process many times, and came up with 60-90 topics each time, and they were somewhat different on each run. Some of the topics are clearly disjunctive (most aptly, the model came up with a topic that Brian identified as “set theory and grue”, but it also found one on “Freud and medical ethics”), and sometimes a nice category on one run doesn’t show up on another.

I just glanced at the entry on the Dewey topic (http://www-personal.umich.edu/~weath/lda/topic05.html) and here is what Brian says about it:

“One of the disappointing things about this model was how it handled pragmatism. Most model runs ended up with a very nice pragmatism topic, that gave you a very clear sense of the rise and fall of pragmatism in the different journals. This model did not. James primarily ended up in the previous topic, Pierce was all over the place, but primarily in Universals and Particulars, and Dewey is here. So we don’t get a single clear look at where pragmatism goes.”

Thanks, Kenny! So I guess I have two questions is: (1) how are the word weights calculated? Is it just by word frequency and correlation with other words (keywords)? If so, that includes a presupposition that what an article is about correlates well with the repetition of a particular categorical word. Reasonable enough, but I do wonder if it is simply reasonable given our current style of writing. (That is, I wonder if it is a less reliable assumption for writing in the first part of the 20th century.) Full disclosure: I have an inherent skepticism about the conclusions based word-use/frequency analysis done by some digital humanities scholars, though I realize that it is quite a popular inference these days. I prefer to think of word-use/frequency as an interesting way in. (2) If there were many iterations of the process, each with different results, what considerations led to preferring this model (with its disappointing handling of pragmatism) over others? That is, what are the biases built into the findings.

I am not really looking for any answers, as I suspect I would find them if I did get myself in gear and read the documentation. Just clarifying what I take the issues to be.

Hi Lisa

Thanks for your interest in this! I should preface this by saying I don’t completely understand what the system is doing, so I could be getting something wrong here. And I fully share your scepticism about this kind of work. Best case scenario we get something that (a) is justified by its results, and (b) can be used alongside other tools – most notably citation records and old fashioned reading the articles. So I really intend this to be an interesting way in.

Small aside to back up this scepticism. The model came up with a topic that looked like feminist philosophy, and which had a huge boom in the 1970s before waning in the 1980s and 1990s. And I was a bit puzzled about why that was. It turned out that there were a flood of articles about affirmative action in the 1970s, more against than for, that the model had lumped in with each other and with later feminist work. But it wasn’t that the discipline had suddenly gone feminist in the 1970s; almost the opposite. And in this case just skimming the articles was enough to see what was happening. So I like the way of thinking of it as a way in. But it is an interesting and distinctive way in. I wouldn’t have, for instance, have come across Dhirenda Mohan Datta’s work without doing this project.

So on (1), it is word frequency and word connection. The model is looking to build k paradigm articles, such that every article in the data set can be modeled as a linear mixture of those paradigms, where k is set by the model builder. (And by article here I just mean word counts – it doesn’t even consider word order.) So it is considering word co-occurence in building the paradigms; it gets much closer to equilibrium if it is sensitive to which words pattern together. Just why this is so is a bit beyond me, but I was staggered at how well it actually works. I thought given that description it would have been totally bamboozled by words that are used with different meanings in different parts of philosophy, especially like ‘realism’ and ‘internalism’. But it mostly wasn’t. The particular model I ended up using did run together free will and political freedom, and all the different thought experiments involving ‘Jones’ confused it. But it worked much better than I expected. It managed to draw pretty sharp distinctions – like separating epistemologists talking about probability from philosophers of science, or metaphysicians talking about space and time from philosophers of physics.

As for the biases built into the choice, I’m sure there are plenty, but here’s what I did to try to minimise them. I ran a bunch of these models. (Sixteen if I recall correctly.) Then I built a few different typicality metrics to see which of them was the most typical. Sadly, there were three that stood out from the pack, but not from each other. And the one I picked seemed to me to best. That last step was, I fear, a bit subjective.

I’m obviously a terrible judge of my own biases. But I think the biggest chance for bias came at the following step. I decided I didn’t care that much if the model split apart things that should go together. I could always put them together manually. (The book is full of graphs where one of the metrics is summed over multiple things the model separated and I thought should go together.) But I did care a lot if it put together things that I thought should be apart. And that really relied on judgment calls on my part. Some of them were pretty easy judgment calls – my second favorite model had this weird insistence that feminist philosophy went in the same bucket as work on metaphysics of material constitution. But some of them were much more subjective. And that’s another reason – beyond the inherent limitations of the model – for thinking of this as a nice way in to the literature, more than the last word on it.

Yes, he has a chapter on each of these! (Notably, he found that if you let the machine get too greedy about optimizing the topics, it finds a “topic” that turns out to just be “how 21st century philosophers write”. But it’s still interesting to see how this “topic” compares with the others when you dive in!)

This is fascinating, but I’m curious about the invisibility of epistemology. I wonder how work on the “new realism” and “critical realism”—much discussed in the journals of the first few decades of the twentieth century, especially the Journal of Philosophy, by writers such as W. P. Montague, E. B. Holt, Arthur Lovejoy, Morris Raphael Cohen, Mary Calkins, Ralph Barton Perry, C. I. Lewis, and Roy Wood Sellars, as well as Dewey and Santayana—figures in the data set. It fits of course under the “mind and metaphysics” heading, but its themes seem to be significantly epistemological, even in the present-day sense.

Yeah, I overstated that here. Elsewhere I was more weasel-y; I think the phrase that use a lot is “epistemology as it is currently practiced”.

Because of course you’re right that these folks cared about epistemology a lot.

At risk of going even further out of my comfort zone, I think the more careful thing to say about the early 20th century works is this. There is very little epistemology that is not connected in some way to metaphysics. You can debate various moves in the Gettier literature, or reliabilism vs internalist foundationalism vs internalist coherentism, without taking on any particular metaphysical commitments. And mostly parties to those debates don’t think that metaphysical questions will be neatly resolved by getting the epistemology right.

That I think is what we don’t see much of in the early literature. These folks are defending distinctive grand philosophical schemes – ones that had implications for what we now classify as debates in metaphysics, mind and epistemology. They mostly weren’t doing the last of these separate from the first two. (For better or worse!)

I’m sure this is too strong as a generalisation, so let me already note one caveat. The paper of Datta’s I mention above is a response to Montague. And the bit of Montague he’s responding to is, or at least could be read as, epistemology that doesn’t depend on a broader world view. Montague is defending what we’d now call reductionism about testimony. And he refers to the rival non-reductive view as ‘authoritarianism’. As a fellow reductivist, I’m really tempted to take that term on. (Even though I’m not sure Montague’s arguments for reductionism survive Datta’s criticisms.)

Thanks, Brian: that’s very helpful. I think you’re right about the inclination to defend grand schemes (or to combat them—idealism being the grand scheme that provoked the new realists).

Brian: in 1960, Ryle published an article on “Epistemology” in Urmson’s “Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy.” It has little resemblance to “contemporary epistemology.” Paul Edwards’s 1965 five volume Encyclopedia of Philosophy does not have a real entry under “Epistemology”. Instead there is this:

EPISTEMOLOGY. In addition to the long survey article, EPISTEMOLOGY, HISTORY OF, the Encyclopedia contains the following articles on topics of epistemology: ANALYTIC AND SYNTHETIC STATEMENTS; APPERCEPTION; A PRIORI AND A POSTERORI STATEMENTS; BASIC STATEMENTS; CATEGORIES; CAUSATION; CERTAINTY; COHERENCE THEORY OF TRUTH; COMMON SENSE; CONCEPT; CONTINGENT AND NECESSARY STATEMENTS; CORRESPONDENCE THEORY OF TRUTH; CRITERION; CRITICAL REALISM; DOUBT; EMPIRICISM; EPISTEMOLOGY AND ETHICS, PARALLELS BETWEEN; ERROR; EXPERIENCE; HEAT, SENSATIONS OF; IDEALISM; IDEAS; ILLUSIONS; IMAGINATION; INDEXICAL SIGNS, ECOGENTRIC PARTICULARS, AND TOKEN-REFLEXIVE WORDS; INNATE IDEAS; INTENTIONALITY; INTUITION; IRRATIONALISM; KNOWLEDGE AND BELIEF; LINGUISTIC THEORY OF THE A PRIORI; MEMORY; MUST; NEW REALISM; OTHER MINDS; PARADIGM-CASE ARGUMENT’; PERCEPTION; PERFORMATIVE THEORY OF TRUTH; PHENOMENALISM; PHENOMENOLOGY; POSSIBILITY; PRAGMATIC THEORY OF TRUTH; PRECOGNITION; PRESUPPOSING; PRIMARY AND SECONDARY QUALITIES; PRIVATE LANGUAGE PROBLEM; PROPER NAMES AND DESCRIPTIONS; PROPOSITIONS, JUDGMENTS, SENTENCES, AND STATEMENTS; PSYCHOLOGISM; RATIONALISM; REALISM; REASON; REASONS AND CAUSES; RELATIONS, INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL; SELF-PREDICTION; SENSA; SENSATIONALISM; SKEPTICISM; SOLIPSISM; SOUND; THINKING; TIME, CONSCIOUSNESS OF ; TOUCH; UNIVERSALS; and VISION.

I cite the whole list because it is somewhat amazing that all these were brought together as “topics of epistemology.”

This is very interesting. However, I think we should think careful about the strengths of the inferences we draw from this about the recent history of English language philosophy. There is obviously a correlation between what topics are considered important at each time and what topics are discussed in journals. However, it is never a perfect correlation and may sometimes be rather weak.

Here are some things to consider. First, some topics (at least at certain times) may be more commonly examined in monographs than in short journal articles. Therefore, you could have a situation in which there was more overall research, or more influential research, produced on topic x but more discussion of topic y in journals because topic x was regularly discussed in monographs whereas topic y was mainly discussed in journals.

Second, sometimes a couple of key works may be very influential and convince a generation of philosophers to largely accept a certain position in a debate, or to think that a certain debate has been resolved. In such cases the relevant topic receives less discussion in journals even though it is widely considered important. Conversely, sometimes certain topics that are not considered that important get a lot of discussion in journals because there are lots of small points and technical moves to be made, or because no consensus has emerged and so antagonists from each side want to keep thrashing it out, even though they would agree that other topics are more important.

Third, sometimes academics just go along with the crowd in terms of the stuff they generally publish even though what they think is important, and what they prioritize when teaching their students is different. For example, there was a time when “write something about Rawls” was good advice for moral and political philosophers trying to launch their careers. However, that n% of the things I am publishing discuss Rawls does not mean that I think Rawls is m-times more important than other topics. Perhaps in my ethics syllabus Rawls would only get two weeks even though most of the ethics stuff I publish mentions him.

Minor query: what accounts for the spike in papers on quantum physics around 2000? A quick scan of the relevant issues of BJPS and PoS doesn’t reveal much of a common thread/cause among those papers on QM (e.g. the Everettian Resurgence) – except that in 1999/2000 PoS published the proceedings of PSA ’98 which had a couple of sections heavy on the quantum, so perhaps that generated the spike. In which case, of course, some of the fluctuations may be due to those kinds of ‘special’ issues … As I said, minor.

It’s what you said about the proceedings. For a few years around 2000 PoS published the proceedings, and this led to a spike in everything.

One of the big challenges of doing this was figuring out which graphs to normalise to the number of articles being published and which to present as raw data. When I didn’t normalise, you get these spikes that are just due to more articles in everything coming out. But when I did, the scales were thrown because the topics from the less specialised eras could be 20-30% of articles in a given year, and then you can’t make out the 1-2% differences that matter in the modern era.

I suspect people who more about data viz could do better than me and handling this problem – maybe normalise and use log scales would help? – but it kind of defeated me.

Somewhat tangential to the main thrust of the post, but D.M. Datta’s paper, which is an outlier, is essentially marshalling arguments found in premodern Indian philosophy about testimony as a response to Montague. That these arguments are ones which “[look] like contemporary epistemology ” says a lot, for me, about the analytic nature of much Sanskrit-language philosophy. And, for those of us who work on it, Datta is well-known for his work in Indian epistemology, authoring the still-classic “Six Ways of Knowing,” as well as an introduction to Indian philosophy, among other publications.

I mention this in case anyone takes the time to read Datta’s paper and finds it compelling–this isn’t to take away from his ability as a philosopher, but to encourage attention to the sources of his knowledge, for those interested. The SEP has an entry on Classical Indian epistemology, for those looking for a place to start.

100% agree with this.

To make it even clearer where Datta is coming from, the paper in Mind is mostly extracted from “Six Ways of Knowing”. And that book is, as it says in the subtitle, a study of Vedantic epistemology.

I don’t know if the first edition of “Six Ways of Knowing” is easily available, but the second edition (from 1960) is on the Internet Archive. And from the citations, I’d guess it isn’t that much changed from the first edition. The Mind paper consists largely of material from its last chapter, on testimony.

https://archive.org/details/TheSixWaysOfKnowing1960D.M.Datta/page/n347/mode/2up

I did something similar with one journal, the AJP: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/23801883.2018.1478233

Oh wow. How did you get the data? I would have loved to include AJP, but they weren’t on JSTOR at the time, and that was roughly the limit of my data collection ability.

The data collection process is described in the paper Brian. My co-author did that bit.