The Philosophy and Politics of Early Abortion in the U.S.

The past months have seen successful legislative efforts in several states to criminalize early abortion. Emboldened by Brett Kavanaugh’s appointment to the Supreme Court, abortion opponents are hoping that the new legislation, once challenged in court, will force a reconsideration of Roe v. Wade, in which the Court ruled that “during the first trimester, governments could not prohibit abortions at all; during the second trimester, governments could require reasonable health regulations; during the third trimester, abortions could be prohibited entirely so long as the laws contained exceptions for cases when abortion was necessary to save the life of the mother.” (Update: see this comment from Legal Detail regarding this description.)

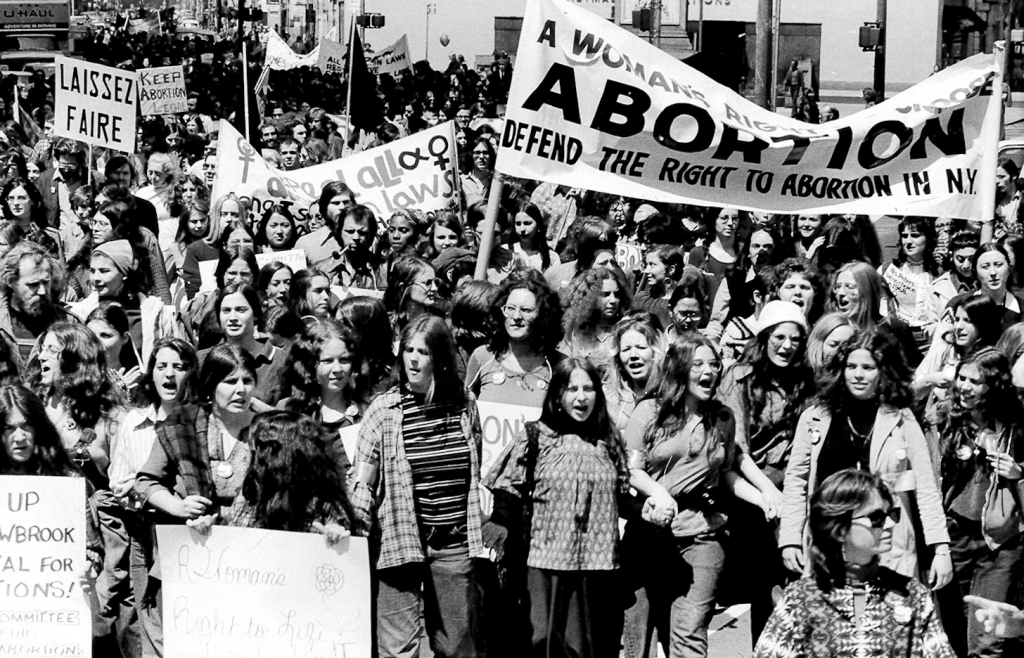

The wave of new legislation is being protested nationally today, at noon, at various #StopTheBans events. (You can check here to see if there is one near you.)

Abortion is a challenging and complicated subject in moral and political philosophy. In a recent post at his blog, Fake Nous, Michael Huemer (Colorado) writes, correctly, in my view:

If the abortion issue seems very simple and obvious to you, then you’re probably a dogmatic ideologue, and your ideology is stopping you from appreciating this very subtle, complex question. Abortion is a highly intellectually interesting issue, connected with all sorts of important—and very difficult and controversial—issues: Issues about personal identity, potentiality, the foundation of rights, the physical basis of consciousness, the doctrine of double effect, special obligations to family, negative vs. positive conceptions of rights, and the problem of moral uncertainty.

When I teach about abortion in my “moral problems” courses the aim, as it is generally in lower-level classes, is to convey the complexity of the subject.

Those concerned primarily with the current events concerning the legality of abortion may have little patience for such complexity. I’m no political strategist, so I’m willing to admit that from a political point of view, ignoring complexity may be the best strategy. I hope it isn’t, but I don’t know.

Regardless, I do think it’s worth noting that an appreciation that abortion is not “simple and obvious” is not necessarily a recipe for political inefficacy.

For one thing, getting people to appreciate the moral complexity of abortion may result in less of the political dogmatism that seems to fuel support for making early abortion illegal.

For another, thinking that the issue of abortion is not “simple and obvious” is compatible with having have well-reasoned, considered judgments on the matter. Philosophers, of all people, are likely to appreciate the complexity of the subject, and I think this makes us better equipped to take part in disputes over it, or to even change people’s minds about it. Being able to engage, one-on-on, with those one disagrees with politically in a way that helps them make sense of not just your view, but theirs, with an honest appraisal of the various difficulties for each, probably has a better chance of changing minds than standing on different sides of a barricade shouting slogans at one another.

This isn’t intended to discourage political demonstrations, protests, and the like. They have their value. But it is just a reminder that the typical readers of this website probably have other valuable tools at their disposal, too, and may wish to seek out opportunities in which to use them.

If readers have particular strategies for such engagement, or particular arguments they think are especially effective in such contexts, feel free to share them.

(For example, I find that talking about the argument that Elizabeth Harman (Princeton) gives in her “Creation Ethics: The Moral Status of Early Fetuses and the Ethics of Abortion” is particularly good for complicating people’s thinking about abortion.)

Please add power dynamics and women’s autonomy to the list of complicated issues related to abortion. What we are seeing today is a backlash against the female–this is a social, political, and economic as well as a philosophic issue.

thank you Katrina Maloney, EdD, MA. consciences and embodiment

I just want to note that Roe’s “trimester framework” was already overruled by the Supreme Court’s decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, so your statement of what legal principle would be discarded in overturning (what remains of) Roe v. Wade is inaccurate.

“Abortion is a highly intellectually interesting issue, connected with all sorts of important—and very difficult and controversial—issues…”

… such as the role of sexual reproduction in underpinning patriarchy (quite literally, historically speaking and to this day), the relation of the normative to the natural (for instance, in the sense that individuals of various species routinely control fertility through culling and other means, including early and not-early humans), and a social context in which duties to children don’t oblige parents of different sexes/genders equally (descriptively/predictively speaking), whether gestative surrogates have rights to abortion, whether sex-selective abortion is permissible, and basically 90% of other issues feminists have been discussing for a very long time.

So, to be fair, it is complex. But the complexity is more complex than Enlightenment-liberal moral/metaphysical discourse can handle.

Thanks for this, Maja.

Maja, would you mind saying a bit more about how the issues you mention connect to abortion debates?

I will try but if I were to do the answer justice, I would have to write a book, so this is an off-the-cuff/rough response. Generally, I think our philosophising shouldn’t be ahistorical, for that disguises contextual information that should make a difference to our arguments. I will stick to the first example I gave: the role of sexual reproduction underpinning patriarchy. It was not so long ago that women and children were legally men’s property in the Western world (and in practice still are in some parts of the world). (And, although the law may have changed, attitudes and sentiments have not changed/changed enough along with the laws.) Marriage, and the imperative to be chaste prior to marriage (for women), and not get divorced secured the patriline (e.g. primogeniture, the last name, decision-making power in the home) in service of the interests of male offspring. It was during this historical moment (not only this historical moment, but including in this historical moment) that Western philosophers theorized personhood, agency, moral obligation, and so forth. It is extremely implausible, in my view, to think that the historical moment did not influence the philosophical terms and views* that came to be accepted. Forbidding abortion functions to support the partiline as did those other modes of controlling women’s fertility. This (as well as the reasons I’ve stated in my other comments in this DN post) is why it is hard to take many “pro-life”/anti-choice arguments as being in good faith. That does not mean that none of them are in good faith; but one would have to be extremely naive about history, politics, and power, in my view to take most of them as good faith arguments.

Of course my claim here stands to the extent that we accept that patriarchy is still a thing. I cannot here (in the interests of space and time) make a sustained argument that it it, in various guises. For that, see: feminism.

*Such views are criticized by many kinds of philosophers, such as care ethicists, materialists, new materialists, and more; such views as are criticized in Margaret Little cited by Paul Franco (in comments below).

In showing why Thomson’s violinist argument fails – and for thinking about abortion in general – I have found Gina Schouten’s paper “Fetuses, Orphans, and a Famous Violinist” to be especially useful. I highly commend it to others. I think this paper deserves far more attention. See it here: https://philpapers.org/rec/SCHFOA-9?fbclid=IwAR2Hy79mDrvvMACML7fYsdqnGFPcXOpsqzCCe-oVkXstLPpQShb8Qce2_jU

One of the main things I want students to get out of my introductory classes is that hard problems require hard thinking to solve them. The complexity of the abortion issue allows me to show them (for nearly every student) that they have deeply held, passionate beliefs for which they cannot articulate even the most basic of reasons (beyond a bumper sticker comment). The hope is that the process helps foster a sense of intellectual humility.

Support for bans on early abortion need not be based on political dogmatism, insofar as that phrase implies anything negative. Many people really believe, not without reason, that the only plausible account of egalitarianism requires that human beings require the same protection by law at all stages of development, and that to be a human being just is to be a human organism (or something like it). Once you have that, there are pretty comprehensive arguments against abortion – Kate Greasley, who is pro-choice herself, gives pretty compelling legal arguments that if the foetus is a legal person, abortion must be illegal in almost all cases.

If some people believe that egalitarianism requires that human beings require the same protection by law at all stages of development, then I hope those who hold those beliefs also believe, *for the same reasons/if they are going to be consistent*, that the draft/war is morally impermissible, that there should be free quality childcare available to all, that there should be robust social safety nets including healthcare provided for all, that there must be robust penalties for pregnancy discrimination and for failure to pay child support, that assisted euthanasia is never permissible, that capital punishment is never permissible, and possibly even that we should ban cars/driving, ban smoking, etc., since they are dangerous, relatively speaking.

*Most* people who cite some reason related to the ‘sanctity of human life’ do not hold these other beliefs, in which case it appears most of them are not arguing for abortion bans in good faith. So it is hard not to read the gist of the ‘pop’ ‘sanctity of human life’ arguments as simply being about controlling female bodies, since that seems to be just about the only context in which the ‘sanctity of human life’ trumps all other considerations for those people.

It is true that there may be some people who do hold these other beliefs I mentioned who also believe abortion should be banned, and engaging the arguments *those* people make may be productive, but I think would lead to a wholly different conception of the ideal social state than is suggested by the “most” people in the US at least who would argue for abortion bans.

Also, mid-way through the above comment, the discussion is shifted from being about ‘human organisms’ to being about ‘persons,’ which is problematic.

Yes, some of us agree with most of those things (I think it is always wrong to intentionally kill human beings, and am a welfarist politically). But I think it’s also somewhat obvious that you can oppose the involuntary killing of innocent human beings without necessarily being committed to banning cars, for example. And that this combination of beliefs does not mean that the only thing one is in interested in is controlling female bodies.

It is regretful that most of these discussions are so America-centric. Most of the rest of us pro-lifers around the world are fine with significant social safety nets.

Sorry, I don’t understand Maja’s comment at all. Thinking all human beings have the same moral status requires thinking we should ban cars? Thinking all human beings have the same moral status requires ignoring the distinction between positive and negative rights? Wut? I mean, someone might as well argue that those who advocate serious gun restrictions are really just anti-hillbilly since they don’t also think we should ban cars. Or am I missing something?

I take the point to be this: Some of those who argue from the sanctity of human for the wrongness of abortion are not consistent in that they do not seem to care for the sanctity of human life in cases other than abortion. If we think human life ought to be protected in the case of abortion then, on charge of inconsistency, we must also favor policies which help to support children, disfavor assisstied suicide, and disfavor capital punishment. But, we may also have to think about disfavoring other things which are dangerous to human life, such as allowing the driving of cars.

However, it is not clear how many people who argue against abortion from the sanctity of human life are consistent when it comes to holding some of these other beliefs. Not everyone who is pro-life is pro-welfare or anti-capital punishment. I imagine not many people on any side are anti-car. But if human life is sacrosanct, it is inconsistent to be pro-life but not these other things. I read Maka Sidzindka’s comment as pointing out and taking issue with this inconsistency.

The majority of pro-lifers do disfavor assistant suicide, and the Catholic Church at least is against capital punishment. I don’t know how we get to disfavoring cars though, unless we’re just assuming some sort of consequentialism about maximizing human life? (I mean, the Catholic Church is against contraception too, so even there I’m not seeing any real inconsistency.)

I don’t know what ‘sacrosanct’ means in this context (the literal definition is something we shouldn’t mess with, which would only generate negative rights), but the view I thought Calum Miller was espousing in the comment Maja was replying to was the view that it’s always wrong to kill innocent human beings. Given a distinction between positive and negative rights, that just doesn’t entail being pro-welfare. Given various plausible theses about the meaning of ‘kill’, it doesn’t entail thinking that smoking and cars should be banned. I’m sure there are some hillbillies who are anti-abortion and pro all sorts of killing, and that their stated justification for being anti-abortion is inconsistent with their overall outlook on killing. And there are all sorts of pro-abortion people who hold bizarre and indefensible views. But why should we talk about them?

About the smoking and the cars: if you hold the belief that human life is sacrosanct, then it may be impermissible to RISK it by driving/riding in cars or smoking. This of course is the weakest part of my argument above, but the argument about impermissible risk would be consistent with arguments about forbidding pregnant women/people to drink alcohol, take various drugs, including prescribed drugs, many of which carry risks for fetuses. (But if we assume the fetus and pregnant woman are morally on par, then by this reasoning we may not be able to oblige women to continue pregnancies for the simple reason that any pregnancy carries the risk of significant complications or death.)

Say killing (of a human life*), as a positive act, is impermissible. But sustaining fetal life requires much more than just not killing it. It requires “the use of another human’s body for nine months. Legally forbidding abortion then, amounts to legally obligating someone to keep another being alive. Even if we grant that the being who is being kept alive is a person, this is strongly at odds with most countries’ legal systems, and especially at odds with American law. Although many European countries have ‘good Samaritan’ laws, which require one to do things such as summon help to the scene of an accident, none have laws requiring citizens to preserve each others’ lives for months at a time. Most American states do not even require the minimal assistance that European law does. American law students are generally taught about this lack of obligation via the example of an Olympic swimmer who sees an adorable child drowning in a shallow pool. The swimmer pulls up a chair and watches the child drown. Students are taught that (in most states) this swimmer has done absolutely nothing illegal (Glendon 1991). If the swimmer is not even legally obligated to effortlessly save the drowning child, how could a woman be required to preserve another’s life at considerable physical cost, and over many months? A right to life that includes the right to such support from a particular person is far stronger than a right to life is generally taken to be” (Saul 2003, from Feminism: Issues and Arguments,” the abortion chapter).

*human as in homo sapiens

The Saul argument seems like a separate line of attack: I wasn’t trying to defend or even take a stand on the abortion debate as a whole, just the claim that it was inconsistent to think abortion was wrong while not accepting those other “pro-life” claims. That being said, there are a few pretty obvious worries about the Saul argument, at least as excerpted above:

1) Abortion does, in fact, almost always involve killing rather than merely failing to keep another being alive.

2) There are certainly laws in the US requiring parents to keep *their children* alive.

3) The philosophical debate about abortion is primarily about its *moral* status, and pretty much all of us think it would be *wrong* for Michael Phelps to fail to save a child drowning in a shallow pool, even if it wouldn’t be illegal.

I don’t mean to suggest that there aren’t responses to these obvious objections, just that drawing the distinction between killing and letting die isn’t going to checkmate pro-lifers.

@ Jane Dewitt: point taken. And I don’t think any claim/argument I have made here *by itself* check-mates the pro-life argument. But, for instance, if fetuses and pregnant women/people are morally on par, then we are granting *positive rights* to the fetus to draw on the gestating woman’s/person’s resources, while not granting the gestating woman/person rights to draw on any resources (not fetal, and not social). Which is a double standard. Of course we could then argue against the idea that this represents a double standard, for instance by saying that a state of fetalhood/childhood is intrinsically characterized by profound dependence, which should make a difference to how we adjudicate this issue. But if we say that then we owe an argument about why the pregnant woman/person should/must be the one to meet certain needs while others mustn’t, and potentially about why the state/others are not mandated to meet needs of various other dependents (the elderly, etc.). Overall point being, if the take a care ethics approach here where dependencies matter and must be built into the moral equation, then it is inconsistent to hold that only fetal dependencies matter.

“I mean, someone might as well argue that those who advocate serious gun restrictions are really just anti-hillbilly since they don’t also think we should ban cars.”

… This analogy doesn’t really help your case considering it is to a large extent true. Part of anti-gun sentiment is rooted in fear, but an equal measure of it is very clearly rooted in disdain for conservatives and people who live in rural areas. This is more or less undeniable given the tone of much of the debate, though anti-gun people will no doubt still try to deny it. We are tribalistic creatures.

I don’t think my argument is too complicated. To sum up:

1. a fetus is a human being (as in, a member of homo sapiens)

2. a pregnant woman/person is a human being (as in, a member of homo sapiens)

3. (allowing, for argument’s sake) different kinds of human beings (members of homo sapiens) are morally on par (morally equal) with one another

4. if different kinds of human beings are morally on par with one another, then different kinds of human beings are entitled to the same (or equivalent) positive rights

5. banning the option of abortion/mandating the continuation of pregnancy amounts to awarding positive rights to fetuses to draw on resources

5. if we award fetuses positive rights to draw on resources (physical, material, maternal), then we must award positive rights to pregnant women/people, and everyone else who is a member of homo sapiens, to draw on resources (physical, material, social)

6. awarding positive rights to draw on resources to fetuses but not awarding positive rights to draw on resources to others, especially pregnant women/people in this context, contradicts #3

Obviously a defeasible argument, but not complicated.

Which is why, if Calum Miller is a sincere welfarist, I wouldn’t take his arguments to be in bad faith (although I may (or may not) still disagree with them on other grounds).

This comment was really helpful to me, sorry if I was being obtuse earlier. I don’t think pro-lifers think of prohibitions on abortions as involving ascribing a positive right to the fetus, but I can understand why someone might be tempted to think that way. However, doesn’t it seem true that if someone paid for an abortion and ended up with a living baby, they’d ask for their money back? I.e., that abortion is a form of intentional killing, rather merely than failing to save?

Seems to me the bar for attributing bad faith to an interlocutor has got to be higher than this: I can draw out consequences that seem to follow from my interlocutor’s view, which she doesn’t accept; therefore she is arguing in bad faith.

As a Nietzschean, I welcome this new and exciting reductio for egalitarianism. Sources?

Margaret Little suggests our philosophical, political, and legal categories–like personal identity, rights, duties to other–aren’t built for the abortion debate and so distort as much as they might clarify. Here’s Little, in her 1999 piece, “Abortion, Intimacy, and the Duty to Gestate”: “When Locke and Hobbes discuss persons, or when modern day battles rage between libertarians and communitarians, the discussions almost always concern the sort of beings who are agreed to be ‘distinct individuals first, and then…form relationships,’ and who, even then lead separate lives. Political and moral theories were developed to deal with this sort of person, with the experiences paradigmatic for this sort of person, for the goods and evils, joys and fears that structure a life as lived by this sort of person. But abortion deals with a situation marked by a particular, and particularly thoroughgoing, kind of physical intertwinement. This means that the fetus, the gestating woman, and their relationship do not fit ready made categories; the question we’re being asked to address falls outside of our theory’s comfort zone” (296).

If Little is right, then, “The central figures in the abortion drama–fetus, gestating woman, and their relationship –are left out of the conceptual paradigm. When we reason about them, we appeal to analogies that are at best awkward, at worst dangerous, but always distorting, for we are trying to analogize to classifications that have at their root the denial of the situation we confront” (296). Little continues, “Abortion asks us to face the morality and politics of intertwinement and enmeshment with a conceptual framework that is, to say the least, poorly suited to the task. A tradition that imagines persons as physically separate might be expected not to do well when analyzing situations in which persons aren’t as it imagines them” (297).

Little then goes on to consider questions about “fetal geography” (i.e., “the fact that gestation occurs inside someone’s body” (297)), forced gestation, intimacy without consent, and the ethics of relationships (especially relationships involving physical enmeshment).

I’ve taught her piece many times to wrap up discussions of abortion, and students across all levels tend to find it accessible and an important perspective.

Thank you, Paul, for introducing me to Little’s work. This fit my intuitions I had before working on the philosophy of symbiosis and pregnancy, while I was teaching intro to ethics & bioethics as a grad student.

Biotech will eventually make things REALLY interesting. For instance, what happens if we develop artificial wombs to the point where viability basically begins at conception and in which removal and preservation of the fetus is no more intrusive than its destruction and removal? Does a right to privacy and bodily autonomy imply an absolute right to destroy the fetus in such cases? What if the government offers to take and raise all unwanted fetuses as wards of the state so that they impose no obligation on the woman? Perhaps the right to bodily autonomy subsumes a right to control one’s genetic material? Things get iffy then, since half of the material belongs to the father. And what if the fetus has a genetic disorder? Can the donor insist that the government raise it but not correct it? Additionally, the more we grant specific choices of technology and medicinal treatments as falling under the scope of bodily autonomy, the more we pave the way for a right to germ-line genetic enhancement grounded in bodily autonomy. A welcome result, in my opinion.

*’viability’ meaning here the ability to fully develop outside the original womb with technological help.

These debates are already happening. As far as I can tell, most pro-choice philosophers don’t think it’s okay to kill the fetus if there’s a way to keep it alive while expelling it. (I believe Bioethics has a special issue coming out on this soon.)

Another complication: can a human being undergo fission? Zygotes can. In my experience this argument by John Burgess (‘Could a Zygote Be a Human Being?’) throws students for a loop.

I’ll put in a plug for a fascinating, thought-provoking recent paper by Gina Rini, “Abortion, Ultrasound, and Moral Persuasion”, Phil. Imprint (2018), which, like Little’s nicely emphasizes the moral complexities of the issue. Whether or not you end up agreeing with her (I don’t), it’s really worth a read.

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/idx/p/phimp/3521354.0018.006/–abortion-ultrasound-and-moral-persuasion?view=image

If we accept the “no-self” view of personal identity, does that mean there is no personhood criterion for when a fetus becomes a person, and so the question of when (if ever) it becomes wrong to abort (and kill) a fetus becomes deflated? Is the existence of a (moral realism-tracking) personhood criterion indispensable to the issue of whether abortion is wrong (due to its effect on the fetus)?

If the no-self view deflates moral questions about abortion, it also deflates a host of other moral questions too.

If there are no human persons, then fetuses are not human persons. There would thus be no case against the permissibility of abortion on the basis of fetal personhood. But then again, if there are no human persons, then adult human beings are not human persons either. And there would be no case against the permissibility of capital punishment (or murder, or…) on the basis of adult human personhood.

(I assume here that the “no-self” view has it that there are no human persons. If that isn’t what the view comes to, then I require instruction as to its proper content!)

Perhaps something like preference utilitarianism could survive an embrace of the no-self view. The move would be something like: who cares whether persons *persist,* if at an instant (synchronically) they have moral worth (in virtue of their preferences at an instant). This might mean giving up on moral responsibility that survives over time, but as Stephen Kershnar argues in a recent book, maybe that’s the right move anyway. In any event, I’m not sure that a denial of personhood-as-such means that nothing is morally wrong anymore.

Isn’t there actually a potential ambiguity here? I take the no-self view to be about the persistence of a distinct individual person over time. But, especially in the debate over abortion, personhood is often defined in terms of the possession of cluster of capacities (e.g. being able to respond to reasons, possessing self-concepts, possessing language, etc.). So understood, it seems like a “person” is a kind of entity. In contrast, the no-self view is about the persistence of a token entity of that kind across time, especially in a way that undergirds the rationality of certain attitudes (e.g. anticipation). Because they’re distinct, it seems like there could be persons without there being persisting individual persons. The resulting view would be that there are super-fine grained series of distinct persons, none of which really enjoy the relation of numerical identity to the others. Thus, there’s no self. But there are persons.

I’ll note that the resulting view may still have trouble making sense of some of the moral importance of personhood in the sense of a distinct kind of entity. But maybe it doesn’t; I haven’t thought about it a lot. Mostly, I wanted to note that there seems to be an ambiguity here that allows for this kind of move. As further evidence of this, consider how some of the capacities cited as central to being a person are rarely cited in debates over the numerical identity of persons across time (e.g. language possession). I’m also open to the possibility that it only seems like there may be this kind of ambiguity because some debates emphasize the capacities possessed by persons because of their potential moral salience.

@ Jane: I could make a mirror argument about negative rights:

1. a fetus is a human being (as in, a member of homo sapiens)

2. a pregnant woman/person is a human being (as in, a member of homo sapiens)

3. (allowing, for argument’s sake) different kinds of human beings (members of homo sapiens) are morally on par (morally equal) with one another

4. if different kinds of human beings are morally on par with one another, then different kinds of human beings are entitled to the same (or equivalent) NEGATIVE rights

5. banning the option of abortion/mandating the continuation of pregnancy amounts to awarding NEGATIVE rights not to be subject to physical interference to fetuses

6. if we award fetuses NEGATIVE rights not to be subject to physical interference, then we must award NEGATIVE rights not to be subject to physical interference to pregnant women/people, and everyone else who is a member of homo sapiens

7. awarding those negative rights to fetuses but not awarding those negative rights to others, especially pregnant women/people in this context, contradicts #3

… in which case it is not clear what should be done, in which case other factors/arguments should be entered. The one that is usually entered is that women/pregnant people are persons, while fetuses are not, and this privileges the rights of women/pregnant people. (Although metaphysical arguments could also be entered about fetuses not being *individuals*, but rather mere parts of (other) persons (assuming individuals cannot be parts of other individuals), in which case the pregnant person may do what she wishes with her mereological parts.) Generally, I think it is true that fetuses are NOT persons (in an Enlightenment liberal sense), and I think that law generally bears this out: fetuses don’t have agency. They don’t count, demographically speaking–are not counted on the census; and all manner of other rights are not granted to them. We should be alarmed by the fact that trying to ban abortion is the reason for legally redefining ‘person,’ not the reverse.

But even if we think fetuses are persons and thus we cannot deprioritize their rights relative to women’s/pregnant people’s rights, it’s is not clear on what grounds we could award the (positive) right to be physically/materially attached to fetuses when no other persons have such a right (roughly, the Thomson argument).

But, one could say, being subject to physical interference is one thing, being killed another, worse thing, so the negative right not to be subject to physical interference is trumped by the negative right to not be killed. However, it is not obvious that being subject to *extremely invasive* physical interference, over the course of 9+ months and being forced (by law) to give birth, is not worse than being killed. (Side note: when one is NOT motivated to go through all that by the desire to have a child, then there is little difference between it and torture.) I think it is this that many people, especially those who have not been or who cannot be pregnant, sadly fail to appreciate. This is why women have sometimes risked death in order to end pregnancies.

Still, most women/pregnant people probably wouldn’t choose death/risk death to secure an abortion. However, that some would, should bring home how important it is to women/pregnant people to have a choice about continuing their pregnancy. Many stop short of risking death, but risk infertility and serious physical trauma.

Furthermore, we can think of other circumstances in which it is morally permissible to subject persons to physical interference and even to kill them, such as in cases of assisted euthanasia (for the reason that the person requested to be physically interfered with) or in cases of brain death/vegetative state (for the reason that there is no hope of that person living a meaningful life in the future) or in cases of war (for the reason that the person was an enemy combatant), etc. We take these to be *special* cases that should be adjudicated in a different way for *special* reasons. But then, why wouldn’t the reason that Margaret Little gives (forced intimacy) amount to a special reason/why wouldn’t pregnancy, a state in which physical intimacy is more profound than in any other state, be counted as a special case in which we should make just those kinds of exceptions as we do with assisted euthanasia, brain death, and war? Isn’t the fact that the “person” is inside of another person enough of a weird/unusual case to warrant special adjudication? As I said above, the lengths people go to to secure abortions should be instructive. (Again, if we ARE going to be moral absolutists about it, then we can’t very well make those other exceptions for euthanasia, etc., and be consistent; we also would have to start counting fetuses on the census and do all the things we would do if we really believed fetuses were persons–naming them, giving them SSNs, etc.)

Another argument that may be entered is a more-or-less utilitarian one about social welfare of a population overall: it is better to allow abortion as an option than to cope with the myriad social ills that come with banning it (including poverty, injustice, or the specter of unwanted children and negligent parents). I’m not a utilitarian but I’m not NOT a utilitarian. I think the ‘social welfare’ reason is one that should make issues surrounding pregnancy/abortion a *special* case (if we think fetuses are persons).

__

Lastly, if fetuses are persons or human life is sacred or whatever, I don’t see how it’s possible to think that female people are not on balance less moral than male people since they’ve had so many damn abortions. Run for the hills. 23.7% or so of female people in the US are murderers.

“Generally, I think it is true that fetuses are NOT persons (in an Enlightenment liberal sense), and I think that law generally bears this out: fetuses don’t have agency.”

Neither do infants and small children. So much the worse for that criterion of personhood.