The “Insanely Low Acceptance Rates” of Philosophy Journals

The dirty secret of philosophy is that we have insanely low acceptance rates—often well under 10% —for papers. This low rate is only defensible if you think that publication in philosophy has the kind of inductive risk that any false positive leads to society’s catastrophe. Nobody thinks that.

Those are the words of Eric Schliesser (Amsterdam), writing at Digressions & Impressions in response to the guest post here the other day on bad referee behavior by Elizabeth Hannon (LSE).

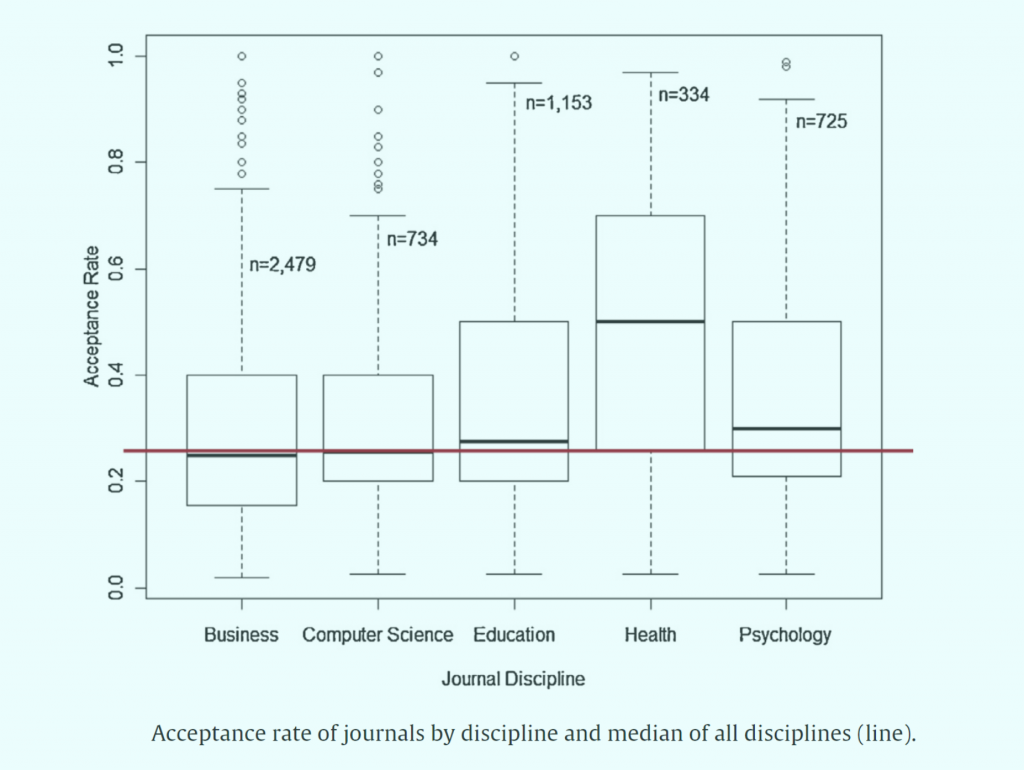

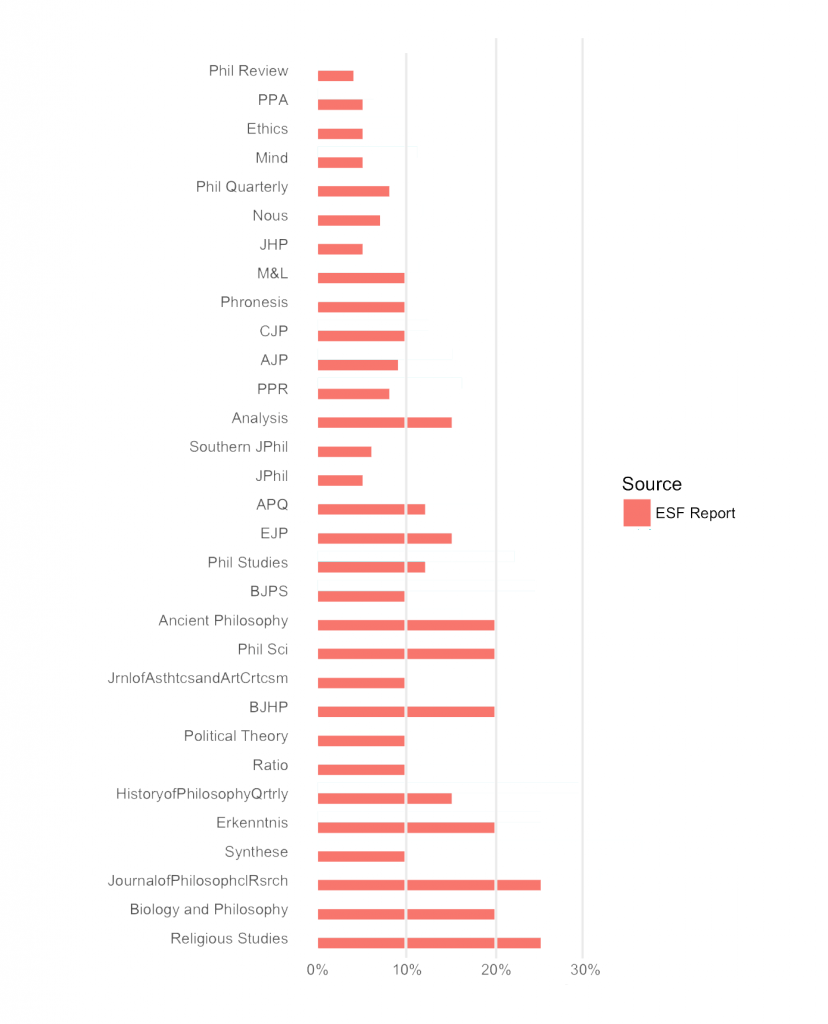

What are the acceptance rates of philosophy journals? Here is data on that from 2011 from the European Science Foundation (ESF) (via Certain Doubts), presented in a graph made by Jonathan Weisberg (Toronto) and originally posted at his blog, that I modified to eliminate information not relevant to our purposes here:

This data doesn’t include all philosophy journals, but it does include many prominent ones, with about two-thirds of these having acceptance rates under 10%. How does that compare to other disciplines? Here is some data from 2013 for some other fields:

from “Journal acceptance rates: A cross-disciplinary analysis of variability and relationships with journal measures” by Sugimoto, Larivière, Ni, and Cronin (Journal of Informetrics, 2013)

Note that the lowest median journal acceptance rate among these fields (in business) is over 20%. Ironically, given Schliesser’s remark about how only a worry that “any false positive leads to society’s catastrophe” could justify philosophy’s low acceptance rates, it’s the field of health—in which, presumably, false positives are more likely to be dangerous—that has the highest acceptance rates!

The researchers responsible for presenting this data note that their sources tend to be incomplete and more likely to include more prestigious journals. This is something it has in common with the ESF data on philosophy. Nonetheless, we should be cautious about drawing direct comparisons with the philosophy data we have. So let’s cautiously say that philosophy journals have relatively low acceptance rates.

As you may recall, Hannon suggested we consider the proposal, “if someone fails to fulfill their duties as referee, the journal will not accept submissions from that referee, for some period of time to be determined.” Schliesser thinks we should direct more of our attention to features of the system in which authors, referees, and editors are operating. He writes:

The high rejection rate has made publication de facto a lottery where those who need publication most are at the mercy not just of the timeliness but also humors of the least appreciated element in the system, the anonymous referee. Because there is a veritable arms race in publication, this means that papers are now routinely submitted early and then improved through a dialectic with the very same anonymous referees…

So, rather than punishing free riding referees (which creates its own collective action and procedural fairness problems), the more rational response… is to increase the acceptance rate in professional philosophy from the the top journals down to about, say, 30% or so…

Given that these days most publication is really electronic publication, there is no reason to keep the number of articles and journal space so limited. My proposal would eliminate a good chunk of the problem in the profession: a lot fewer papers would be shopped around (releasing valuable editorial and referee time); young scholars, who meet the minimal professional competence the discipline expects, would not be part of an unfair lottery anymore; and the sense of mystique and prestige surrounding publication in a top journal would disappear. Multiple publication would still be a sign of (would-be-)productivity and professional competence, but journal publication would stop being the proxy for extremely fine-grained (and in my mind absurd) differentiation of judgments of quality. That’s how it should be. Also, it will halt the excessive nature of the arm’s race; with that higher acceptance rate people will be less impressed by any extra publication beyond what is taken to be the new normal.

As Schliesser notes in an update to his post, his proposal echoes one made here a couple of years ago by Neil Sinhababu (Singapore) in “2,000 Spaces For 10,000 Papers: Why Everything Gets Rejected & Referees Are Exhausted,” in which he argues that we should “work towards creating a lot more journal space (maybe 3 times as much as we have now) for… additional papers to be published.”

Comments and suggestions welcome.

The result would be a new arms race with a goal of publishing as much as possible with even less attention to quality.

That could be mitigated by pairing it with Jennifer Whiting’s proposal for “Slow Philosophy.”

An excerpt:

“What would happen if the APA were to set guidelines for the maximum number of pages on which a tenure decision should be based? Suppose, for example, it were 100 pages – or even 175 – of what the candidate takes to be his or her best work. Of course no one would be prevented from writing – nor even from publishing – thousands of pages. But the letters of referees and departmental recommendations to deans, as well as the deliberations of departments, ad hoc committees and administrators, would all be restricted (officially at least) to the merits and demerits of the designated corpus.”

The proposal is attractive, but it seems like it would be inappropriate to have a one-size-fits-all page range for philosophy as a whole. Some kinds of philosophical scholarship lend themselves to condensed writing much, much more than others do.

“What would happen if the APA were to set guidelines for the maximum number of pages on which a tenure decision should be based?

Most universities would ignore it, because the APA can’t set standards like that, and other departments, which play a role in tenure decisions at most universities, won’t care what the APA says anyway? I mean, this isn’t actually hard. The APA can make recommendations (they can’t “set standards”) bu you have to have some reason to think that university administrators and other departments will care. What are the reasons to think that? Unless you can give good reasons to think that, it’s just making stuff up. When people talk about various things they think the APA “should do”, I often wonder if they have any idea what the APA is. This looks like one more example to me.

Serious additional question: for those who cannot get a work published in a journal, what stops you from just publishing it online? Say, in a Medium or a WordPress or a Quartz blog? If the goal is the dissemination of new knowledge, and it’s clear the paper has valuable information or perspectives, or arguments, in spite of it’s being ‘unworthy’ of journal publication, why not just put it out there?

Blogging platforms have made it dirt-simple to get set up, and publishing in a matter of moments. Many of them have spectacular typesetting, and a few even support LaTex, RST, and Markdown (with a couple plugins). Lots of you folks use blogs already, to rant incessantly (I’m looking at you, Brian Leiter). Why not stop ranting, and start publishing something valuable?

The most commonly cited reason against this that I’ve heard is that this can make it more difficult to get the work published for early career philosophers since reviewers so often unblind themselves by searching the paper. Of course, even if one is completely on board with the point about dissemination of knowledge, they still need publications if they are to have a career.

“Serious additional question: for those who cannot get a work published in a journal, what stops you from just publishing it online? ” If you can’t get work published in a journal, then it might be worth reflecting on whether it’s a good idea to try to disseminate it in its current state. I’d consider–rather than focusing on publishing it just yet–aim to submit it to conferences/workshops, where you’d receive valuable feedback. After some revising in light of that kind of feedback, you might then attempt to publish in a journal again. (Publishing rejected work on the internet just for the sake of publishing isn’t likely to do yourself or your readers much good).

Perhaps if the publication rate is this low, then there are too many young philosophers.

Occam’s razor suggests so few articles are accepted because the quality of the scholarship is poor. A higher quality paper could be read quickly and easily. A paper with a high quality idea that’s familiar to the community is easier to referee as well, as the ideas are known ahead of the me, and the objections have already been met in the paper itself.

High quality ideas are formed by discussion, study, debate/

dialectic, etc. Conferences, colloquia, talks, and email threads are how that happens.

This issue has a similar feel to another I’ve been considering recently–the less inflated grades philosophy instructors tend to give, relative to other disciplines (I’m guessing this is a general trend, but I only have evidence it’s true for some universities). If the relevant external parties knew that our standards were higher (e.g., for journals, the people making P&T decisions, and for grades, the people seeing transcripts, like law schools and employers), then it would be neutral or even good for us to maintain those higher standards. But if those parties don’t know (and I fear they don’t), then we are only punishing ourselves–namely, our young colleagues and our students. Assistant professors look like they are publishing less than their peers in comparable departments. Philosophy majors have GPAs a notch below their peers in comparable departments (e.g., our best major graduates with a 3.9, having gotten all As except a couple A- grades in tough philosophy classes, and then competes for law school admission or jobs with, let’s imagine, equally or less qualified poli sci or history or psych majors with 4.1 GPAs, since their majors give out A+ grades).

What to do? Alas, getting the rest of the world to raise their standards for publications or grades may be a tough sell, and I’m not sure how to get the information out to the relevant parties. But I don’t want to argue for for lowering standards either. (In the case of journal acceptances, I’m dubious the standards would have to be lowered much to increase publications 20-30%, though as I’m sure other commentators will point out, there’s already too much published to read and too much not worth reading…)

I’m not a fac member, so I might be wrong, but why think the people who need to know how hard it is to pub in philosophy don’t know that? hiring and tenure decisions are made by faculty in philosophy (with pro forma approval by higher-ups afterward), right? So it isn’t likely someone’s application for a job or tenure is going to get shot down because they “only” have X publications, for some X that is very good in phil but not very good elsewhere.

hiring and tenure decisions are made by faculty in philosophy (with pro forma approval by higher-ups afterward), right? So it isn’t likely someone’s application for a job or tenure is going to get shot down because they “only” have X publications,

My impression is that this depends a lot. At some universities, there are university-wide (or college wide) tenure and promotions committees that have to approve tenure decisions, even after the department votes. This can be a place for a lot of fighting. If historians have to have two books to get tenure, they will sometimes not be so happy if a philosopher can get tenure with 5 articles, and if the Sociologists need 10 articles, they won’t be happy, either. Philosophers can, of course, try to ‘education’ people on local standards, but the others may not really care about those standards. This can lead to thinks like (for example) no one getting tenure in Philosophy at Penn for more than 10 years at one point.

Do philosophers have a harder time getting tenure than faculty in other departments? There are some universities (notably Harvard, Princeton, and Yale) where tenure standards across the university have been ridiculously high, and there are *many* departments in those universities where no one was awarded tenure for many years. I don’t know if Penn is a university like that, or what the statistics are in other departments.

Universities, and colleges within them, are quite aware of the fact that publishing standards are very different in different fields. I’m not so sure that philosophy is distinctively unrecognized as a discipline with its own standards.

I’m not sure, Kenny – I was just an observer to all of this (an interested one, but fully on the outside of deliberations, other than what people told me.) I had heard that there were complaints from other departments about philosophers not publishing like _they_ do, and so hesitation to give them tenure with, say, 5 good articles, if that wouldn’t be enough in their fields. That seems like it would disfavor philosophy, but I don’t know. I do know that things have changed there somewhat, but why, exactly, I can’t say. (There are some philosophy-friendly people in high admin there now.) I do think the tenure rate at Penn was very low by university standards for some time, but now is much better.

The relevant parties I was describing are “external” (i.e., *not* philosophers ‘in the know’ about the difficulty of publishing in at least highly ranked journals, or about the more difficult grading by philosophy instructors). So, I was referring to college and university Promotion and Tenure committees (which are composed of faculty from various departments) and administrators making P&T decisions, above the departmental level. These parties only know about the higher standards (where they exist) when philosophers tell them, and sometimes they might think we are biased…

Our tenure decisions are made by a committee outside of philosophy (if there is a philosopher on the committee, they have to recuse themselves). For my tenure decision, I included stats on journal acceptances to make the case that publishing in philosophy is more difficult than other fields.

At UW-Madison we have done a good job of educating our external tenure & promotion committee about what’s expected for philosophers. I realize that’s not as easy at other institutions. Still, I’m more worried about educating external bodies like grant-funding agencies, to whom we have less immediate and authoritative access.

“journal publication would stop being the proxy for extremely fine-grained (and in my mind absurd) differentiation of judgments of quality.”

As a regular referee at some of the top journals, I never make recommendations based on small differences in quality (I can’t, of course, speak to whether editors do the same). Most of the papers I see have serious philosophical (or other) flaws in them, some of which could be remedied through one or two rounds of revisions and some not. Of course, I may be an overly critical referee or someone who receives a disproportionate share of papers from the “crap pile.” But I can’t see how increasing acceptance rates would affect the judgements I make unless the editor indicated a higher toleration for R&R judgements for papers requiring more substantial revisions and a higher number of rounds of revision.

Hrm. I think the quantitative account isn’t very interesting, without a qualitative account. Can we compare the content of accepted to rejected, and get a picture of the delta? Are there any trends that can be identified in the content, that would signal “acceptance” vs “rejection”? Is there anything about phil paper submissions that set them apart from, say, rejected submissions to a rigorous scientific journal? Or a rigorous literary journal? Or a rigorous business journal? Could it be that philosophy journals receive many more low-quality submissions than than these other fields?

Also, without a qualitative account, what can really be said about the numbers themselves? Why is it called “low”, let alone “insanely low”? Low, compared to what? Is comparison to other fields really a good measure? What’s the “correct” acceptance rate for philosophy, and for other fields? Would 50% be about right? Would 80% be too high? Why?

Maybe I’m asking questions to which you folks already have answers. In any case, it seems unclear to me how a judgment like “insanely low” makes any sense, without knowing what’s in the papers.

I’m sure arms races are alive and well in all those fields with relatively high acceptance rates. So I doubt increasing acceptance rates for philosophers to publish would do much to halt the excessive nature of the publication arms race. Each one of us would still have incentive to publish more than everyone else so long as it makes us look a bit better than them. This remains the case so long as one’s overall number of publications retains some value as a signal. It’s true that having one more publication than your rivals likely won’t do the trick anymore, but having three or four or five or ten more would.

But the higher acceptance system might still be a better system. Not because it halts arms races, but because it changes the way they work.

However, if publication inflation got bad enough it could make hiring committees shift to other signals. Since publications and pedigree are the main coins of the realm at present, this might make pedigree even more important than it is now.

And that – making pedigree even more important than it is now – would be a bad thing. In my view it should not be a consideration AT ALL, since it tends to reinforce social privilege.

One thing that the data doesn’t capture is average time spent on manuscript before publication. My friends in math, psychology, and computer science spend years on their manuscripts before submitting them. Philosophers…well, I’ve seen people try to shop a paper around after about a month.

Another factor is that other fields are often collaborative. When you have multiple people looking over drafts, quality generally improves, so it’s unlikely that, say, 5 people would agree to send out a manuscript before it seemed ready.

Anecdata only, but my experience has been that mathematicians and computer scientists write more papers faster than philosophers do — but many things that become journal articles were first presented at fully peer reviewed conferences with pre-pub proceedings.

I am in a Math department. Pure mathematicians are slow, and generally publish very little comparatively. Applied mathematicians publish lots, and much of what they do is in science journals, rather than math journals

To me the bigger problem with low-acceptance rate is the complete randomness of acceptance. The truth is for those under 10% of papers that do get accepted, there is at least as many papers that are equally good that for reasons of pure luck (or worse, lacking connections) are not published. There is simply not that fine grained of a difference that explains the papers which are accepted and those that are not.

I find it hard to believe that a genuinely good paper would not make it through at least one referee process. If your paper gets rejected by 10 journals, it’s probably not good. It’s true that lots of bad papers get published. It seems to me publication is only a lottery for papers that shouldn’t be published.

There are plenty of examples of good articles that have been rejected multiple times before being accepted. Some of these stories end with the article being accepted by a more prestigious journal than the ones it was rejected by. I’m not sure I know of an example that involves 10 rejections, but I do know of one that involved 7 or 8. Readers are welcome to share their own examples.

There’s some discussion of that at PhilCocoon, including a quote from Jason Stanley on a paper of his which was rejected 11 times, here:

http://philosopherscocoon.typepad.com/blog/2015/09/stanley-on-peer-review.html

Beware the availability heuristic, Justin 🙂

Touché.

Anna

Even if we grant that for every paper accepted there is one rejected that should be published, that does not suggest the system is broken. These other papers can be sent to other journals – it is highly unlikely that a deserving paper will not find a good home. I have played this game a long time. I have had my share of rejections, but good papers get published.

Also, I disagree with Sam. While some papers in other disciplines take years, so do some papers in philosophy. Likewise I know some papers in other disciplines that are written very quickly.

I’m not at all a fan of this proposal. As a grad student especially, it’s very hard to keep up to date with literature. There’s far more stuff out there than I have time to read, and I’m not experienced enough to easily be able to tell which articles are worth that limited time, and which aren’t. That an article has been published in a top journal is a very useful proxy for its being more likely to be worth the time to read it, at least for an inexperienced person like me.

If suddenly, say, Ethics and PPA start pumping out three times as many articles, and I have no way to tell which of them would have been accepted under the old regime, the result is going to be that I’ll be spending about 2/3 of my time in those journals reading articles that would not before have been judged of a high enough quality to be published in those journals. Of course, the review process isn’t perfect. Many of these articles might be better or similarly good to articles which would have been published under the old regime. But unless the review process is completely broken, one would expect accepted articles to generally be of better quality than rejected articles.

There’s also the question of how this could be put into practice in the first place. Journals are free to publish a higher proportion of submitted articles, if they so please. I suspect that any top journal doing this to anything like the extent suggested here (tripling the acceptance rate) would experience a sharp decline in reputation in fairly short order. I think that decline in reputation would be justified, on the grounds above: I doubt the review process is *completely* broken, so I expect that an increase in the acceptance rate could only come with a decline in quality. So even if this is a good idea (which I dispute), journals have an incentive to ignore it anyway. That incentive will only vanish if most philosophers can be convinced that acceptance rates can be tripled without a significant loss in the general quality of published material. Well, good luck with that.

In general, I think we should be striving for more quality in philosophy, at the cost of less quantity. This proposal seems to me to push in the opposite direction.

That an article has been published in a top journal is a very useful proxy for its being more likely to be worth the time to read it, at least for an inexperienced person like me.

= = =

I have not found this to be the case at all. Indeed, quite the opposite. Some of the most interesting stuff is published in non-top-venues.

Seems to me that associating very low acceptance rates with quality, without much more substantial qualification is a mistake.

Dan, I think you’re misunderstanding Tomi’s point. I’m also a grad student, and I can tell you that my first priority (for purely prudential reasons) is to find and cite every paper where my failure to cite it would cause a ref to reject my submission out of hand. As far as interestingness goes, I’m primarily concerned with saying interesting things, not reading interesting things. That, too, I think, has prudential support. Now, it’s true that some of us want to read interesting papers (I don’t, really; I don’t enjoy reading nearly as much as going to talks and chatting with people about their views), but the sort of proxy Tomi seems to be talking about has nothing to do with that.

But wouldn’t the outcome you’re worrying about here (referee rejects because one relevant paper isn’t cited) become both less common and less disastrous if the proposal under consideration is accepted?

Also, without wanting to be cruel: I’m not sure it would be a tragedy if people who don’t much want to read interesting papers got weeded out of the profession. (People like that are, in practical terms, an unreachable part of the profession to me, since I doubt any of them are going to get on a plane to come to Turkey to chat with me about my views.)

Well that was mean 🙁 I was just stating my preferences parenthetically! Didn’t know my place in the community was on the line

Another way to make this argument would say that the fact an article was published in a top journal is a very useful proxy for reviewers to consider it an article you *should have* read and responded to. For an inexperienced author in a non-ideal world, this seems at least as useful a proxy, especially when journals reject 90% of articles.

There is a big difference between empirical and non-empirical work. Journals in other fields are often reporting the findings of expensive trails that are expected to be competent but nothing more. Write-ups of these experiments are expected and often encouraged to be fairly formulaic in academic journals. Referees mostly skip to the methods section.

There are at least three important contrasts. First, other fields can more easily self-sort based on the quality of the results. Second, other fields can more easily self-sort based on the funding for the study. Third, it is a lot easier for a reviewer to admit that data disagree with her previous work than a logical argument.

I like this proposal for the sake of scholarship. Even if reviewers don’t change their standards, it would leave editors with more freedom to accept papers. I’m not optimistic that it would help with the publishing arms race though. The arms race is more a product of the job market, which this proposal doesn’t address. But one problem at a time.

Accepting more papers would work, but I’d also like to see the creation of lots of open-access niche journals. Why not have a “Journal of Nonconceptual Content” or “Journal of Virtue Epistemology”? Embracing an open working-paper model of writing would help as well. Journals seem to serve two purposes right now: getting your own idea out there (and a line on your CV), and having a place that promises to only publish quality philosophy papers (whatever that means). I don’t see why both of those purposes couldn’t be better served by alternate models.

This is a really good and important idea. I think philosophy has way, way too few top quality specialist journals. I gather from talking to folks in other departments that the role of generalist journals in philosophy is much bigger in philosophy than it is in most of academia. Some new journals (on the model perhaps of Semantics & Pragmatics) that publish top quality stuff in relatively specialised fields would really help things.

I like this idea in general. It seems to me that there’s a pretty fair amount of it in value theory (a couple, at least, of aesthetics journals; several philosophy of law journals, some even more specialized; several political philosophy journals, some somewhat more specialized, particularly as to approach; some “applied philosophy” journals, including several specialized ones; etc.) Perhaps oddly, there seems to be fewer _just_ normative ethics or mostly meta-ethics journals, but perhaps I’m just not thinking of them now. Is this somewhat less so in other areas of philosophy? (I can think of lots of specialized journals off the top of my head, but outside of philosophy of science, I’m not sure how well they are respected.)

Unless hiring committees are willing to take those journals as seriously as they do generalist journals they don’t much help early-career researchers (except indirectly insofar as senior people publishing elsewhere frees up room for others).

And there’s the issue; the point of publishing is to get tenure, not to explore philosophical issues.

I don’t disagree, but that’s an inevitable fact of academia. Most of us have to make a living after all.

Somehow it manages to work in other fields. If mathematicians can understand the distinction between the “International Journal of Number Theory”, the “Journal of Number Theory” and “Research in Number Theory”, and tenure writers can convey these distinctions appropriately to committees, then philosophers should be able to do the same thing.

I *love* the idea of way more niche journals. For one thing, that would make our jobs as researchers considerably easier by alleviating philosophically meaningless legwork. Hard to see how to get them off the ground in general, but perhaps there are models worth studying. (Journal of Nietzsche Studies? Seems to have worked, in large part because prominent Nietzsche scholars backed it early on in various concrete ways.)

But what’s striking about that, to me, is that increasing the number of niche journals *alongside* pushing up the acceptance rates would possibly defeat the whole point. If a generalist journal like PPR explodes, presumably the number of articles on (e.g.) Nietzsche therein will too, and so then I’d just have more PPR journals to scour through *in addition* to keeping up with everything JNS puts out.

I think there are a lot of good suggestions here, and I really like the pairing of Justin’s suggestion about higher acceptance rates paired with Saul’s rules about tenure files. But I have to admit that I’m a bit despairing about there being any will to solve this problem. In fact, I think it’s likely just the opposite and I suspect that many journals more or less deliberately cultivate these insanely high rejection rates and do so for reasons that are unique to philosophy. Unlike the sciences we lack standards for what constitutes good work that are clear, meaningful, and more or less universally accepted. (Now I’m sure I’ll get a lot of push back on that claim and people will cite standards as counter-examples, but I’d also bet they’ll be so vague as to allow huge latitude for interpretation–i.e. things like “novelty” or “rigor”–or they’ll be the posters own idiosyncratic standards.) So I think that one way that people try to make up for this is by using high rejection rates as a proxy for high quality since we lack other standards. Any journal that loosens it’s standards will almost certainly for that very reason be perceived as lowering it’s quality and any journal that’s getting off the ground has every incentive to set arbitrarily high rejection standards so that they’ll be perceived to have high quality.

“So I think that one way that people try to make up for this is by using high rejection rates as a proxy for high quality since we lack other standards.”

Adding to this: although practices are changing philosophers tend to use citations rather sparingly. As a result it is harder to judge journals (and articles) on the basis of ‘impact’. If philosophers cited each other more then perhaps less weight would be given to journal selectivity.

I meant Whiting not Saul. Oof do I feel stupid.

But anyway one other random thought I had is that if anything false positives are much less bad in philosophy than most fields since in philosophy they can actually be productive in ways they generally can’t elsewhere. I’ve often learned a lot from articles or books I thought were dead wrong precisely by figuring out why they were dead wrong. So if the search for truth is what the whole publishing racket is about (though I don’t think it is sadly) that’s one more reason for journals to publish more.

So we’ve heard it’s (a) the referees and (b) the low journal acceptance rate. Could we consider how far out journals look for referees?

I’ve published a couple of papers on human rights over the past several years. I’ve reviewed a few papers, but not really that many. I was contacted once last year, for a paper in medical ethics. I have not been contacted at all this year. Are journal editors really reaching out to all of the resources available to them? Could we have a poll or something? How often are readers contacted to review papers? in my case, not very often.

I get asked to review journal articles about once a year. I’m certainly not a big name in my main area of research, but I do publish stuff intermittently and feel qualified to review papers in my AOS. I’m not necessarily clamoring to perform more service to the profession, as I have a 4/4 load and onerous service requirements at my school, but I could probably handle more than one article a year.

I’m the same. I would do 3-5 a year if asked. But I’m not asked. I wonder if this is a conscious decision by editors, or if we have just fallen off the radar.

As a journal editor, I can tell you that it’s very rare to make a conscious decision to stop asking someone, unless they’ve taken an inordinately long time for reviews they’ve agreed to do, on multiple occasions. The problem is that our “radar” isn’t very good at finding the people that aren’t immediately on everyone else’s radar. I could imagine that there might be a way to better keep referee databases so that they’re more useful for this purpose, but I haven’t figured out how yet.

This should be paired with a discussion of how often people should referee a year. This has been discussed elsewhere on DN (Justin: perhaps you could link that if you recall it?) but 3-5 seems very low to me.

Good point, it is linked to the other discussion. My initial thought was roughly one paper every quarter, because I could fit that into my schedule without too much trouble. (And my point above was really that I’m not even invited to do that much!) More could be a bit of a problem, given other demands on my time. But I’m happy to do some reviewing, even if I don’t submit a lot of papers myself, just because I read certain journals.

Can you say more about what makes it seem, not just low, but very low? You might set the number at significantly higher than five a year? Referee one article each month? FWIW, I’m at a teaching school with some research expectation. The right number for anyone will likely vary depending on some particulars: teaching load, number of preps, other service, and so on. But I’m open to the discussion.

Still, whatever the number, I can’t help wondering if there isn’t a large, untapped well of referees out there.

I was basing my number off of what other people I know report of their own reviewing (didn’t someone elsewhere in this thread say they do 12+ a year?), and my own. Perhaps some of us do way more than we need to.

So let me walk back some of my comment: 3-5 seems much lower than a lot of people’s normal routine. To figure out the normative claim I think we should have this conversation (which I take it you agree with), and yes, it will definitely have to depend on commitments.

And I don’t mean any of this to disagree with your suggestion that there is an untapped well – I just think we should have both conversations around the same time.

My rule of thumb is to do four reviews for every submission of my own, figuring that if my submissions are accepted 25% of the time, then I’m pulling my weight. In any case, it seems to me that those who are submitting more are asking for more and should be correspondingly more willing to review.

“Given that these days most publication is really electronic publication, there is no reason to keep the number of articles and journal space so limited.”

This is really not true. At least, it isn’t true the way things are currently done. The cost of actually putting ink on pages and sending it around the world is a relatively small fraction of the cost of publishing papers. The more substantial costs are (in ascending order)

1. Hosting the papers somewhere that is stable, easily accessible, and properly indexed.

2. Typesetting the papers

3. Copyediting the papers

If you want to use real copyeditors and typesetters, that’s a few hundred dollars per paper. Publishing, say, 200 papers/year (as the proposal suggests) would be rather prohibitive at this rate given current budgets.

Now perhaps we could publish papers as they come in, with spelling mistakes everywhere, non-standard (and occasionally incomplete) bibliographies, etc. But I’m not sure that would be the best thing to do. We could try to cut down the costs of 2 by publishing the template and requesting authors do their own typesetting, but Imprint has done that for years and I think it’s far from universal that authors are willing/able to help out.

It just isn’t cheap to run a journal, unless you want one that really really looks like it is run on the cheap.

Agree with you that there are more costs than is typically assumed. But maybe we could still cut some of them down. For example, paying typesetting costs seems unnecessary if a publication is digital only. Even a web-based template system could work well enough.

As a proof of concept, do Medium articles look really really cheap? They look nice enough to me. Medium gives authors very little control of how their articles will look and authors basically just paste text into appropriate blanks. Then Medium’s system makes it look decent. There is no other way to publish with them so all authors follow the rules. Some clever person could figure out how build something like that for online oa journals (if they haven’t already.) We just need to be able to post neat legible text to the web with sections, footnotes, etc. and also have the option to download in a few different formats. Not sure what the initial system would cost, but, over the long run, it would likely be much cheaper than paying for typesetters.

Especially if several oa journals split the upfront costs, which is perhaps unlikely…

Thanks for this explanation Brian. Perhaps you can’t share these, but I would definitely be interested in seeing some concrete numbers on how expensive this is, and I imagine others would as well. Perhaps if people had a greater idea of how the process works – plus the fundraising process to start a new journal – we could go about setting up some more as has been suggested in other subthreads, including one you participated in.

For my part, I’m wondering why we can’t ask authors to do 2/3 themselves, perhaps in a peer-edit type scenario (i.e. if I get a paper accepted I must edit at least one other before my paper is actually published). I would agree to participate in such a scheme myself.

I want to echo what Tomi said: increasing the number of articles published solves one problem (a gatekeeping problem about jobs and promotions), but it worsens another. It’s true that publishing more entails more paper (unless we move to electronic publication), more copyediting, more typesetting, more hosting. But that’s not my worry. Publishing more means that engaging with the literature gets increasingly difficult. That’s a burden that can fall especially hard upon on younger, less powerful folk, it’s a burden that can fall especially hard upon people obligated to teach higher loads, and I’m guessing it makes it more likely that we all silo a bunch.

I’m not saying that publication is a good measure of quality (though the published articles I read are, on the whole, much better than the ones I have seen submitted to journals, for some anecdata). I’m saying that some professional pressure to limit publication volume has merits beyond mere logistical merits.

(That’s not exactly what Tomi said; consider my comment allying with Tomi, in case some of what I said goes beyond the original comment!)

If the acceptance rate at the top journals increased, then some of the less well regarded journals might just fold. Or else the quality of papers they published might diminish so much that you would feel very little inclination to consult them.

Bug or feature?

I’d say bug. Plenty of journals – perhaps all – have biases as to the topics they accept, even if they’re supposedly “generalist” journals. There are well-known examples of this, especially in ethics. If those journals just continue to accept more papers of the same narrow topic or style and the smaller journals fold, the field is left without those other perspectives, which in some cases will be bad (perhaps not in all).

If the same papers that the smaller journals publish now were still being sent to them, there would be no reason for them to fold. Admittedly, that might happen if only a small fraction of the papers they publish now are of sorts that better-known journals won’t publish because of various blinders. But I’d expect there to be plenty of non-mainstream journals left, even if some of them had to expand their remits and consider papers on wider ranges of topics than they do now. The journals most likely to close might actually be ones like the journal I edit, Utilitas. We’re not a generalist journal, or even a general ethics and social-political journal. But I assume that a majority of the papers we publish were sent somewhere else first, like Ethics, PaPA, or a history journal. If those journals started accepting more papers then we might see our submissions dry up, at least those of publishable quality.

Regardless of whether it’s a bug or a feature, if it’s actually to be expected, then it means the proposal is self-defeating.

I may be missing something (since I can’t access the source of the data for other disciplines due to a paywall), but it looks like we are comparing the acceptance rate of 31 of the better known philosophy journals to a sample of 100’s to 1,000’s of journals in other disciplines. Surely, if the number of philosophy journals considered were broadened to an equally broad scope, then the average acceptance rate would also increase significantly? (Or if we only looked at well-known journals in other disciplines, their average acceptance rate would decrease closer to that of the well-known philosophy journals?) It may be that philosophy journals have lower acceptance rates, but I don’t see anything in the data presented that gives significant evidence for that hypothesis.

It’s very possible that the figures for other fields even include open-access journals in which authors pay for their papers to be published.

A quick and unscientific look at the acceptance rate of super-prestigious science journals:

Nature: 8% (https://www.nature.com/nature/for-authors/editorial-criteria-and-processes)

Science: “less than 7%” (http://www.sciencemag.org/site/feature/contribinfo/faq/#pct_faq)

Nature Physics: 7% (https://www.nature.com/articles/nphys3516 ; my calculation)

Physical Review Letters: “fewer than 25%” (https://journals.aps.org/prl/authors/editorial-policies-practices)

The Lancet: “around 5%” (http://www.thelancet.com/pb/assets/raw/Lancet/authors/lancet-information-for-authors.pdf)

New England Journal of Medicine: “around 5%” (https://www.nejm.org/media-center/publication-process)

Journal of the American Medical Association: 4%-11% (https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/pages/for-authors)

Increasing the acceptance rate would not stop the publication race, and would not even diminish the proportion of rejected papers. With a higher rate of acceptance people will submit even more papers that they are submitting now, since the quality standard to get a paper accepted will be lower.

So remember the other day when we saw that over 50% of philosophy articles were *never cited*? Or was it *read*; I forget. And so now the proposal is that we have 3x as many papers? Even if the additional papers were as good as the first group–which they wouldn’t be, presumably–we’re just wasting e-trees publishing stuff nobody cares about reading. And so then publishing devolves to vanity projects wherein people are mostly publishing only for themselves–you could say T/P, but who would tenure or promote someone for work that isn’t even being read…? So, no, that isn’t the response.

To summarize: publication rates are really, really low. Readership rates are also really, really low. Increasing the former exacerbates the latter. If we try to separate these two variables, what’s the way forward on *increasing both*? Idk, but Schliesser’s proposal can’t be the answer. Cool data, though.

I agree that the system is grossly unfair to those submitting papers. However, the ultimate purpose of publishing is not to serve writers but readers. If demand for philosophy papers exceeded supply, it would make perfect sense to try to publish more papers. However, if the supply of philosophy papers far exceeds the demand for philosophy papers, the best move is not to increase the number of papers published, but to revise a system that requires people to produce so much work that isn’t in demand.

I think there’s a danger of over-simplification in just looking at acceptance rates. At a guess, 80% of the referee reports I write recommend rejection or major revisions, but I hardly ever write a referee report that says “intrinsically publishable but not likely to be competitive with better papers”; almost always, when I recommend rejection it’s because I think there’s a major flaw or flaws that makes the paper unpublishable. So in the journals I referee for (and at least in the areas I referee for) I think the publication rate is about where it should be; to increase it, I’d have to be recommending papers that I don’t think meet adequate scholarly standards.

Conversely, reporting from colleagues at the prestigious open-field journals (Mind, JPhil, Nous etc) is that they’re vastly oversubscribed and that there’s a significant amount of comparative assessment going on. I agree that it is bad if papers that make a genuine and substantive contribution don’t get published because there isn’t room. I also agree it’s bad if the referee system, through pressure to make implausibly fine distinctions, becomes unreliable and capricious.

As I’ve said before, I think a lot of this would be improved by a move away from the top journals in the field nearly all being generalist journals. That’s a weird feature of philosophy that’s not matched in the sciences (I don’t know about other humanities subjects). This is already the case in philosophy of science, where you can have a very strong CV just through publishing in BJPS and Phil Sci (I have only one – joint-authored – paper in a generalist journal), and anecdotally I think the refereeing process works rather better in philosophy of science than in other fields. Perhaps there is space for one or two super-competitive journals that aim to publish the best work across the field – rather as Science and Nature function in the sciences (each has an acceptance rate around 7%) – but it ought to be possible to have a very strong CV by publishing in the top specialist journals. Those journals would then be in a better position to provide informed refereeing and to assess whether they ought to be publishing more (or fewer!) papers.

When I first read the opening discussion, I wondered what as an editor I could do to increase the acceptance rate, given that I don’t get many (any) reports that say “intrinsically publishable but not likely to be competitive with better papers.” But then I realized that there might be an answer. Right now, negative recommendations weigh a bit more heavily with me than favorable ones. The quality of the reports obviously matters, as does my own assessment, especially if the paper is one that is solidly in my own wheelhouse. Just because one reviewer recommends rejection doesn’t mean that we won’t eventually take the paper. But there’s a presumption against. I could reverse that presumption and give more weight to favorable recommendations when referees disagree, if I had more pages to fill. That would probably result in a few more papers being accepted even if reviewers wrote precisely the same reports that they would have otherwise.

I think the more-specialist-journals proposal—which Brian Weatherson also advocated above—pushes the problem to a different place.

Within philosophy, there is clearly a hierarchy of subarea prestige. For example, philosophy of physics seems to me seen as more prestigious than, say, feminist philosophy. (One might witness this by how comfortable a philosopher of physics is in opining outside their subarea of expertise on, say, a philosophical topic like gender construction, compared to the converse analogue.)

That means that, even on this proposal, some specialist journals will remain more prestigious than others, just in virtue of their subarea of coverage. For example, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B might be seen as more prestigious than Hypatia, simply due to the existing hierarchy of subarea of prestige. Although it creates a different kind of hierarchy, the generalist journals seem to function as a way to counteract the subarea hierarchy; for example, a feminist philosophy paper in Journal of Philosophy might be seen as good as a philosophy of physics paper in the same journal. And that, as described upthread, has obvious implications in hiring, and to a lesser extent, in tenure and promotion.

There are obviously some advantages to the more-specialist-journals proposal, but I think this is a disadvantage that is worth considering seriously.

I’m not sure I buy the first-order claim about hierarchies of prestige. I think it’s more situational and context-dependent than that. (And you can’t move in many areas of philosophy without someone confidently asserting something silly about physics.)

I’m also not at all convinced that having specialist journals makes a difference here. The (hypothetical) biased prestige-minded person who prefers SHPMP articles to Hypatia articles is equally capable of saying, “sure, they both have articles in JPhil, but one is a philosophy of physics!!!! article whereas one is only feminist philosophy”.

But most importantly, I think it’s a bad policy to prioritize the credentialing function of journals over their primary role of effectively disseminating research. And that’s doubly so when we’re talking about such uncertain and hard-to-measure effects on the credentialing function.

I was thinking that, in the imperfect world we live in, unfortunately the effective dissemination of research is strongly tied to credentialing. In general, a paper on say gender construction is likely to get read much more if it were published in Nous as opposed to Hypatia. Again, I regret this state of affairs. But I think it’d be unrealistic to think about the two roles independently. More generally, I think it’d be unrealistic to think about the role of journals divorced from its place in the ecology of academia as an industry.

P.S. I’d bet that the silly things said about physics are much more likely to come from higher prestige subareas (e.g. metaphysics) than lower ones.

P.P.S. I do think there’s a lot of contextual and situational variation, but there’s also a general pattern that holds up robustly across contexts and situations.

“In general, a paper on say gender construction is likely to get read much more if it were published in Nous as opposed to Hypatia.”

That’s interesting and possibly points to other field-specific differences that are relevant. A paper in philosophy of physics is going to be more widely read by its intended audience if it is published in BJPS or SHPMP than if it is published in Mind (although it doesn’t make much difference, because most people will read the article via online archives anyway). I was very much thinking in terms of communicating to fellow specialists, rather than to philosophers in general. I guess I agree that if you want people well outside your area to read your paper, you need to publish it in a generalist journal. But (I take it) even that’s not very effective, because *perhaps* except for the very top few journals, no-one reads them all.

I certainly think there’s a place in the philosophy ecosystem for a small number of very-prestigious generalist journals that publish papers of exceptional significance and wide interest – that’s basically the ecosystem niche occupied by journals like Science and Nature in the physical sciences, and the Lancet in medical science. What I’m arguing is that below that very small level we’d be better served by top-tier more-specialist journals, rather than by second-and third-tier generalist journals, such that you could have a successful career publishing only in those journals. Those journals will be better able to source expert referees, authors will know where to submit their papers to rather than all queuing up to apply to the generalist journals in perceived order of prestige, and readers will be able to find relevant work better.

I acknowledge and appreciate that I mostly only know the philosophy-of-science ecosystem and there may be other problems I’m not recognizing. But the philosophy-of-science ecosystem seems to function a lot better than the main philosophy ecosystem so it’s not absurd to suppose that there are transferrable ideas.

PS on the side topic of hierarchies of prestige and their context-dependence, FWIW my experience in philosophy of physics is that (a) people tend to abstractly think that what you’re working on is important and that you must be very smart, but (b) they are skeptical it has any particular relevance to their own work or teaching needs… so how that translates to relative status is complicated.

–But most importantly, I think it’s a bad policy to prioritize the credentialing function of journals over their primary role of effectively disseminating research

It may be bad policy, but it’s the functional policy in many theoretical science fields.

In the fields of discrete mathematics and theoretical computer science, journal publication occurs *years* after the result is known and disseminated. Research would not go forward if it relied on journals.

Results are disseminated by word of mouth, seminar talks, and email. Conference proceedings produce a more formal outlet for publicizing results, and that forum provides a check on the reliability. The submission for the printed proceedings formalize the result, and the preprint for that proceeding is sent everywhere.

Journals in these fields exist to credential the proofs.

Perhaps philosophy should figure out how to disseminate results without journals.

But it’s the high prestige areas that most need specialist journals. I’d love it if there was a top notch metaphysics journal, and maybe a handful of specialised journals within metaphysics. If we had specialist journals everywhere, then the generalist journals could focus exclusively on papers that are interesting because they cut across, or don’t fit into, existing disciplinary structures. And that would be really good for disrupting some of the lazy hierarchies.

@Shen-Yi Liao: I can only assume that you have precognitive powers, since when you posted this I don’t think I’d commented publicly in my life on gender construction, and now I seem to be doing it.

I can say in my defense only that (a) I hope I’m cautiously inquiring and exploring rather than “opining”, and (b) if anyone with a gender AOS wants to contribute to the next DN thread on quantum field theory, I promise to be nice to them. 🙂

Slightly off topic, I know, but I think that the ‘lottery’ problem would be helped by having editors who were more pro-active in their judgment about referee reports. I may be biased here because I have just received back two reports, one of which says (in effect) ‘publish as long as the author excises section 2 entirely’ and the other of which says (in effect) ‘publish as long as the author makes much more of the material in Section 2’. The editors say to respond to both comments! So, I’m stuck in this weird dilemma of having to both do X and not X, or trying my luck with another journal (which might have two section 2 lovers or haters). I can’t believe I’m unique among philosophers in receiving this kind of feedback (if only because I’ve seen it before) but my colleagues in other disciplines seem bemused by my predicament. Given that philosophy seems to create this kind of problem, it would be really useful to have editors who are more pro-active and say, for example, ‘ignore referee 1’ or whatever. Even if that involves my paper being rejected, an ediItor who wrotes’ whatever reference 2 said, o agree with referee 1 and hated section 2, send it to journal of stupid ideas’ , would be useful.

I’m sure you didn’t write this asking for advice, but as a referee I have often given advice that is approximately of the form, “Section 2 is a different paper from the rest of this paper – the author should reduce section 2 to a suggestive paragraph and save the rest for another paper, or turn section 2 into the main body and save most of the other ideas for another paper.” In this case, you don’t have good guidance about which of these is the better project, but doing one of them, with an explanation of what you are doing in the response to referees, is likely the best bet.

“and the sense of mystique and prestige surrounding publication in a top journal would disappear”

In the actual ecosystem of academic philosophy, this sense of “mystique and prestige” is exactly what’s desired. I would be glad if that wasn’t the case, but I don’t think tinkering with the publication process or acceptance rates would change the fundamental dynamic. With academic employment of a desirable sort such a radically scarce good, and with so many qualified people out there chasing those few positions, there *is* going to be a race to separate oneself from the pack.

Wouldn’t the reputation of any journal which did that plummet, since reputation is largely tied to scarcity?Is the idea that the top philosophy journals will collectively decide to accept 2-3 times as many articles as before? That seems extremely unlikely to happen. I fail, though, to understand how this is anything like a ‘proposal’.

Usually I’m all about idea theory….but I think critics of the system need to start proposing solutions that we can actually take some immediate steps toward implementing in a way that will make an appreciable difference.

(Thanks for the interesting post nonetheless.)

Synthese and Phil Studies manage to have pretty good reputations, despite their tarnishment from a reputation of publishing huge page counts because Springer wants them to.

About Eddy’s comment at the top about whether tenure & promotion committees know this, I think they are often told in the letters from outside referees. I know I talk about it to put things in perspective when they are comparing with their home disciplines. I’d guess many people do so that most files will have someone who does this.

Also, FWIW, I think philosophy probably has more disagreement about which papers are good and about what they need to be good enough. That would likely increase the number of times a paper would need to be read before someone thinks it ready to go.

Yep, the letters (and philosophers on the committees) often discuss the difficulty of publishing in philosophy. But such ‘pleas’ can sound self-serving to people outside philosophy. Data might help. So if the data reported in the post are legit and can be put in a clear, easily interpretable graph for administrators, I’d love to have it (as a dept chair). It better be comparing apples to apples, though…

I’m inclined to say we eliminate the journal model entirely. So far as I can tell there is no reliable quality control at all. In the age of the internet there are much better ways of disseminating ideas. This one blog post will probably be read by more people than any article published in any of the journals mentioned in this article all year.

There are two different ideas here. One is that there is no reliable quality control over the process. The other is that blogs, or other online publications, are more widely read than journals. I just want to say that you have given no evidence for the first claim, the one about quality control. I have a lot of anecdotal evidence that there is a lot of quality control: papers are read and examined carefully by editors and referees. It is very, extremely unlikely that a good paper will not be published at all — this does not mean, of course, that it is very unlikely that it will be published in the journal of first choice of the author.

And the reason why a blog post “like this” will be read by more people than any article in any of the journals mentioned in this post is true — if it is true — because this blog post is on a topic that interests philosophers working on all philosophical sub-disciplines, because it is short, because it does not require specialised knowledge. and because it does not demand a lot of mental effort and concentration. Most articles published in the journals mentioned in this post are very different from this post in all these features.

I meant: *this does not mean, of course, that it is very unlikely that it will NOT be published in the journal of first choice of the author*.

It seems pretty clear to me that the problems with our publishing system (super slow, low acceptance rates, low citations, poor referee reports) could all be solved by reducing the competition for jobs. This means admitting less PhD students and closing down many PhD programs.

Increasing article acceptance rates will do nothing. This will just cause article inflation, thus causing early career PhDs to just need to publish even more articles. The solution in question is like saying we’ll fix poverty by simply printing a million dollars to give to every poor person. Prices will skyrocket!

We can’t lower the ‘price’ in articles that a job costs in real terms by inflating the value of articles.

I should have said,

We can’t lower the ‘price’ in articles that a job costs in real terms by inflating the number of articles.

“This means admitting less PhD students and closing down many PhD programs.”

Or increasing the number of decently paying philosophy positions at colleges and universities (and high schools, for that matter).

*We* can’t increase the number of decently paying philosophy positions (if “we” refers to philosophers). But *we* *can* to a larger degree control the number of PhD students and programs.

“This low rate is only defensible if you think that publication in philosophy has the kind of inductive risk that any false positive leads to society’s catastrophe.”. Not at all. The low rate can be defended by the reasonable decision to publish only what is of the highest quality. Does this mean that many good or interesting papers which are not of highest quality would never be known to the world? Not at all: everyone can post his or her own work online now, and one often sees such online, unpublished papers being discusses both in other online papers and in published papers too.

An important side note: the picture that arises from the ESF report cited by Weisberg is quite different from the picture that arises from the APA blog survey: https://blog.apaonline.org/2017/04/13/journal-surveys-assessing-the-peer-review-process/

While the numbers for Phil Review look equally hopeless in both cases, for almost all of the other journals cited, the acceptance rates look much better on the APA blog data. According to the latter, almost no journals have acceptance rates below 10%. Phil studies even comes out as having an acceptance rate of 24%. I am not quite sure what explains this discrepancy, or which of these data sets is more reliable, but I suspect that maybe reality is not as dire as the ESF data tells us.

The statistics on the APA site are based on self-report. They are thus quite imperfect. They may be helpful for giving people a rough impression of the relative likelihood of publication in different venues. They’re very helpful for giving junior scholars an indication of which journals review papers promptly and which take a long time. But as an indication of actual acceptance rates, statistics based on self-report are useless.

If you compare philosophy to the hard sciences you would probably expect this finding. This is largely because philosophy has less “pre-screening” and relies more on journal screening; hard sciences have a much easier time screening things before submission.

1) Hard-science papers are functionally limited in production because they often require you to do a lot of hard science before you write the paper. A *good* philosophy paper takes a ton of time and work, of course, but “a paper” in general can be submitted more easily as the bar is lower. When production cost of a thing is lower, you get more of that thing.

2) Hard-science papers are often capable of producing specific results. Assuming the researcher is familiar with the literature and expected outcomes, then the researcher can (and do!) exercise submission bias; theywill not submit unless the results are good. This also acts to filter out bad submissions and increase the apparent number of acceptances.

But in philosophy there is less of an objectively apparent distinction between irrelevant/interesting/outstanding/bad papers. Even if the argument isn’t actually supportable, it can nonetheless appear novel. So there is less incentive for authors to voluntarily pre-screen.

Also, in a large part of the sciences the “is this project interesting enough to do” question is answered at the grant-application stage. Once you’ve got the money to do an expensive experiment, journals are probably going to publish it provided it’s solid science, but the process of getting the grant acts as a filter (with, to be sure, its own imperfections and biases) on what science is worth doing in the first place.

I want to second Brian W’s suggestion here. There are lots of reasons that Philosophy of Science flourishes as a sub-discipline, but one of them is because there are a high-quality set of specialized journals that informally work together to not poach each other’s papers, and also that recognize when a paper is more appropriate for a more general journal like Philosophy of Science or BJPS.

But the comparison to empirical fields has some limitations. Say I write a paper on the synthesis of beta, beta-substituted amino acids, there isn’t going to be a whole lot of doubt that I did what I said (I am required to show spectroscopic data, etc.). The main question of where the paper should be sent and published is one of the scope of general interest. This example is one where the paper could (and was!) published in the Journal of Organic Chemistry, but a narrower synthesis might find its place in Biopolymers. A more generally applicable method that is novel in some substantial way might go to an even more general journal like the Journal of the American Chemical Society. No one would send a synthesis paper to Science or Nature unless it was cold fusion based, or had implications for the existence of life on Mars.

Chemists are pretty good at figuring out where to send what … and desk rejections reinforce this at the margins. This lets referees focus on issues like over-selling, competing hypotheses, etc., not judgements of prestige and certainly not judgements about whether or not the experiment really worked (the equivalent of whether the argument is really sound?).

All of that said, I think a clearer recognition on the part of philosophers that specialized journals are totally appropriate for specialized materials would be a very good thing indeed. As to higher level tenure and promotion committees, I have a lot to say about that on another occasion.

I remember the phrase that 90% of everything is, well, garbage. Hence, philosophy is right on target. The over proliferation of publishing for tenure, etc…, seems to have led to the idea that everything submitted should be published? And could the journals accept 90% of submissions?? Seriously?? The volume of submissions has surely overwhelmed the ability of journals to publish more articles.

What I object to is the “old boy network” wherein established names’ articles are accepted to the detriment of new and younger scholars who do not have a reputation yet. How are they to get that rep if always superseded by the “old boys”? And, please, don’t tell me the old boys’ articles are always better.

Another reason not to increase the number of professional journals to accomodate all that we write is that our work is in demand by non-professionals and yet we write so little for them. Instead of directing so much work to venues where our work is not in sufficient demand, we might write more for other venues. Increasing the number of journals to accomodate all we produce would be a little like dealing with a food surplus by giving away more food to people who are stuffed and satiated, instead of sharing food with the hungry.

This is a simplification of course. Work written for other professionals does have value, even in a hyper-competative market. Likewise, it isn’t wrong in principle to found a new philosophical journal for professionals. But I think that the general point stands.

It would be useful to know how Philosophy compares with other specifically Humanities disciplines like History or English? The MLA Directory of Periodicals allegedly gives acceptance rates, but of course my library is not a subscriber.

My general impression from talking to colleagues in the Humanities disciplines is that the journal acceptance rates are pretty bad all around. Some hard data would be useful.

I really don’t understand what problem _exactly_ the proposal is meant to solve.

Is the problem that nobody at all will publish most of the papers philosophers are producing? Then there’s no problem, since there are all sorts of people who will publish whatever paper you care to write, and it’s even possible (as others have pointed out) to publish yourself on your own blog.

Is the problem that _elite journals_ are only publishing a small fraction of the papers they receive? Well, that’s why they’re elite journals, and that’s why they’re respected and read. If those same journals started publishing 90% or 100% of the articles submitted to them, then most people would give those journals less attention and would probably look for some other more discriminating journal to help them filter out the bulk of the articles that are unlikely to be worth their time (and it would be hard, and probably impossible, to prevent more discriminating journals from cropping up). It’s hard to see what positive net effect this would achieve.

Is the problem that, while one can publish whatever one wants, it’s hard to get people to read it? The way things are now, philosophers read the articles they want to read and have time for, and then stop. They realize that there are other articles they haven’t read, and they could find ways of getting those other articles — by reading everyone’s private blogs, for instance, or publicly asking for people to send them more articles. But they almost never do this. That seems to suggest that, by and large, philosophers are already reading all the articles they have time to read and want to read. How would it help to jam several times the existing number of articles into the top journals?

I don’t believe it, that is, I don’t believe Anna’s assertion above that for the alleged 10% of papers that *do* get published there’s a further 10% that are equally good that don’t. I have refereed for fifty journals (not all of them strictly philosophical). I often let papers through on the grounds that although they suffer from serious defects, they might just advance the debate and are at any rate no worse than a lot of the stuff that gets published. The papers I reject are the ones that don’t meet that low bar. If I were to drop my floor of acceptability by a couple of storeys (by recommending acceptance for three times as many papers) then I would be letting through a lot of papers which in my opinion did not have anything original, worthwhile or intelligent to say and were often stodgy, turgid and badly written into the bargain (Of course if more papers were published then more papers would be ‘no worse than a lot of the stuff that gets published’ but I can get around this problem by rigidification: I say we should not be publishing papers that are worse than many of the papers that *currently* get published, something that we could reasonably expect if the number of published papers were trebled.) Now perhaps I am an unusually generous referee and the majority of my colleagues are lot more pernickety than I am. Maybe I am the guy who is finally letting through those hitherto multiply rejected masterpieces. It’s other people that are keeping the publication rates down out of sheer capriciousness and meanness. But assuming that I am not, that is , that my rejection rate is about average, what the proposal amounts to is this. In order to foster the careers of young philosophers we should publish 200% more papers, most of which would not be worth reading and would remain largely unread. If that’s what we have to do to help them then perhaps it would be better if they remained unhelped.

But in fact the proposal would not be helpful anyway. I would like to make three points, some of which have been anticipated above, particularly by ‘Postdoc’

1) If lots of outlets were to drop their standards so that more young philosophers were able to publish their stuff, then papers published in journals that did NOT go along with this trend would be at a premium. If it is known to be more difficult to publish in journal X than in journal Y then publishing in journal X would be a big differentiating feather in a candidate’s cap. Thus the likely consequence of *trying* to implement the Schleisser suggestion would be

a) that many more ho-hum papers would be produced

but

b) that the prestige hierarchy amongst journals would be reinforced, with hiring, promotion and tenure decisions being made on the basis of that hierarchy.

2) If per impossibile, *everyone* agreed to the proposal, then the number of a candidate’s publications would be a poor guide to that candidate’s ability, and hiring, tenure and promotion decisions would have to be made on other grounds eg. pedigree with all the Matthew-effect regressiveness and the old-boy-network biases that that entails. Alternatively, hiring decisions would have to be made by requiring some competent person to read through the huge stacks of papers supplied by the candidates with a view to determining whether a candidate’s papers were the usual sort of stuff, fit only for the unread oblivion to which they would be destined, or whether she or he might actually have something intelligent to say. It is hard to think of a better recipe for cultivating misanthropic capriciousness. As I have argued elsewhere – at http://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2012/10/refereeing-obligations-for-journals-where-one-has-published.html and http://www.newappsblog.com/2014/05/the-many-problems-with-peer-review-yet-again-and-some-proposed-solutions.html – *one* reason why referees are sometimes unsatisfactory is that the burden of refereeing falls disproportionately on a minority of the profession who consequently suffer from burn-out. But if you think journal referees are unreliable, biased and capricious, what would you expect of over-worked search committee members ploughing their way through mountains of sub-par stuff in the hopes of finding the occasional nugget of philosophical gold? (Remember that there are often *hundreds* of applicants for any given position. ) If the decisions of referees nowadays are often biased, capricious and unreliable then the decisions of such search committee members could be expected to be a whole lot worse.

3) As noted by ‘Postdoc’ if more philosophy papers were published then the career-enhancing value of a publication would be subject to inflationary effects *at least in so far as philosophers are competing with one another* . What about the career-enhancing value of philosophers’ papers when competing with *other* academics, as for instance when applying for promotion or tenure at an institution that can’t afford to give tenure or promotion to too many people? Here it might be of some assistance but ONLY if other academics were unaware that philosophy had relaxed its standards by 200%. But since this is not the kind of thing that could be kept secret, this is a condition that would not be met. A Philosopher’s papers would be discounted by their non-philosophical peers if those peers knew that publication rates in philosophy had been deliberately trebled to improve philosophers’ chances when competing for tenure or for promotion with non-philosophers. In other words, the proposal would *only* help philosophers competing with other academics if other academics did not know about it. But they would know about it. So it would not help.

As a conjecture, no statistical evidence, I believe academic philosophy is more like a cult than a legitimate discipline. Only bona fide cult members are allowed to publish.