Peer Review or Perish: The Problem of Free Riders in Philosophy (guest post by Elizabeth Hannon)

“Here’s a radical suggestion, using the only weapon/motivational device editors have: If someone fails to fulfill their duties as referee, the journal will not accept submissions from that referee.”

The following is a guest post* by Elizabeth Hannon (LSE), assistant editor of the British Journal for the Philosophy of Science (BJPS), regarding “bad behavior” by referees. It puts forth for public discussion a proposal about how to address such behavior—the proposal has not yet been adopted as an official journal policy. (A version of this post first appeared on the BJPS blog, Auxiliary Hypotheses.)

Peer Review or Perish: The Problem of Free Riders in Philosophy

by Elizabeth Hannon

As any journal editor will tell you (at length, possibly via the medium of rant), the trickiest part of the job is not the papers, not the authors, and not even the typesetters. It’s the referees. It is no mean feat to secure referees who are, first, reliable in their academic judgment, second, responsive to emails, and third, willing to return reports when they say they will. But the frustrations of editors aside, the far more pressing concern is for the career prospects of early-career researchers. Jobs and funding can depend on timely decisions. Indeed, whether an early-career researcher gets to become a mid- or late-career researcher can depend on whether a decision is made in a reasonable amount of time.

Common bad behavior from referees includes (but is not limited to!):

- Failing to respond to invites in a timely fashion (where timeliness is calculated in days not weeks), even if it’s only to decline the invitation;

- Agreeing to act as referee and to return the report within an agreed timeframe (in the BJPS’s case, four weeks), only to substantially exceed this timeframe (by weeks, sometimes months) and

a. asking for this substantial extra time for the weakest of reasons*;

b. not communicating with the relevant editors whatsoever; - Returning a report long past the agreed timeframe, and that report being almost useless;

- Not returning the report and not responding to emails enquiring about the report.

Opinions differ on the obligations of academics as referees. Is it unpaid labour, an act of charity towards the community that ought only to be gratefully received? As much a part of the job as teaching and writing? Something in between? Whatever the answer, authors need more from referees than they ever have done; more depends on papers being reviewed in a professional, timely manner. And at the very least, there’s a ‘pay it forward’ case to be made: A paper sent to the BJPS that isn’t desk rejected can be expected to be read by at least six people (and that’s not counting the work that goes into any resubmissions). For every paper an author submits, other people have attended to their work in detail. The author, qua referee, might be expected to return the favour.

I’ve been lucky to witness some extremely productive philosophical engagement between authors and referees. When it’s good, it’s so good. The only shame is that so much of this is hidden. The process viewed en masse—the view one gets as an editor—is primarily one of cooperation and collegiality, and it’s a wonder that puts the lie to the notion of philosophy as anything like an individualistic endeavour.

But what to do about the bad referees, the system’s free riders? Relentless pestering and various forms of emotional blackmail fall on deaf ears. At the BJPS, we operate a flag system for persistent offenders, but all this amounts to is bad referees being asked to perform fewer reviews, while good referees carry more of the load.

So here’s a radical suggestion, using the only weapon/motivational device editors have: If someone fails to fulfill their duties as referee, the journal will not accept submissions from that referee, for some period of time to be determined. The time period should reflect the severity of the dereliction of duties. For instance, agreeing to act as a referee but then disappearing off the radar might warrant the most substantial ban. Delivering a meager report that’s extremely late, and without communicating with the relevant editor about the delay, might mean some shorter period of time on the bench. First-time offenders surely deserve different treatment to persistent re-offenders. And the embargo period will need to be substantial enough to be effective (too short and it will have no real impact; too long and it’s probably not practical due to the changes in the editorial team). The details can be ironed out.

It’s not just badly behaved referees that stand to suffer here. There’s a risk for the journal in question too: bad referees aren’t necessarily bad authors, and we risk losing good papers to other journals by refusing those authors’ papers. But the problem is so rife and its upshot so dire for early-career researchers that maybe something more radical is required to make clear what is expected of referees and ameliorate, at least to some degree, the problem of free-riders. All thoughts on this proposal very welcome!

— — —

* ‘I decided to go on holidays’ and ‘I have other deadlines that I decided to prioritise after agreeing to referee this paper’ are the problems, not the excuse. On the other hand, there are perfectly good reasons to be delayed in returning a report. Not only do we understand, we’ve been there. You are not the droids we’re looking for.

Art: Yelitza Diaz, “Transformation” (installation) (photo by J. Weinberg)

Excellent idea. Two suggestions for improvement:

(1) Form a consortium of journals willing to adopt this policy.

(2) Exempt untenured researchers from the penalties (or better, don’t put the burden of refereeing on them at all via inviting them to referee, if feasible).

I think a lot of problems could be solved if we found a way to make refereeing count in the way publishing does eg some exchange rate, with say 5 reports equalling one published article.

First, people who do this work get rewarded. Second, people who want to do more such work aren’t penalized relative to others. Third, with this incentive we’d eliminate the back log. Fourth, this means quicker turn around times for everyone. Fifth, that would in turn help out ECRs and make the system fairer for them.

This doesn’t really solve the free riders problem above, in that bad reviewers still benefit, but they’ll benefit less relative to the good reviewers.

Won’t this incentivise quick and dirty reports, quantity over quality? Not so. Journals can still black list people who don’t make sufficient effort, removing them from the pool, so if anyone did want to do lots of refereeing they’d have an incentive to keep the standards high.

Problems: hard to say ‘I refereed these articles’ whilst retaining anonymity over the process, and service / publishing loads are set by the university not us. These are challenges but I think some smart cookies in our discipline could figure out and coordinate something. Perhaps you can get some ‘receipt’ of your report as proof, but which doesn’t give anything away.

Publons (https://publons.com/home/) could be enlisted to perform some of the functions you mention.

I’m sympathetic to the idea, but if “not accepting enough invitations” is not listed as an instance of bad behaviour, it will make it even harder for editors to find referees.

Maybe make it a positive incentive instead: Publish reviewers’ names alongside with authorship, so people can use this on their CV’s and preclude people from this privilege, if they didn’t submit their review on time and with the expected quality.

I wonder if that would create a stronger disincentive with respect to recommending publication. Right now, if I review a paper, recommend publication, and later learn I failed to catch an error in the paper—well, I might feel dumb, but it wouldn’t do much (if anything) to my professional reputation. That’s different from my name being right under the author’s, which is sort of a “THIS IS RICK’S IMPRIMATUR; BLAME HIM IF THE PAPER SUCKS” thing. I would probably be more inclined to err on the side of rejecting papers—or my review time might take a lot longer as I combed through the paper’s references myself.

Now, that’s not necessarily a bad thing (might even be a good thing, if one thinks that too many papers are published already), but it seems like a plausible consequence. Would be interested to hear people’s thoughts.

This is an interesting idea. However, I share Rick’s worry above. I also worry that if I know that my name will eventually be revealed to the author, then I may be less honest and critical when evaluating the paper. More specifically, I may be less likely to suggests R&Rs. For suppose I suggest an R&R. The author might make revisions but also might resent having to do it. Then, when my name is revealed, the author might resent me personally. This would be especially bad if the author is Big Name Senior Philosopher and I am No Name Junior Philosopher.

Rick: If reviewers will take greater care as a consequence that seems to address precisely what was initially perceived as the problem…

But I think the phenomenon of appeasement raised by Philodemus could be a problematic consequence of de-anonymization of the process.

One mitigation could be to publish reviewers in batches every year or so and leaving it unclear who reviewed which article.

I recently reviewed a paper that I thought was really interesting and original, and strongly recommended publication. (As it turned out, that journal didn’t accept it – a problem on its own, as the other referee’s comments, which I was only given later when I complained, were pedantic and silly – but it was very quickly and rightly published in another good journal.) It turned out, as a complete surprise to me, that the author is someone I’m friends with. I had no idea at all she had written this paper. But, I wouldn’t have liked to have my name listed as a referee, and probably she would not have liked it either, as it would have easily looked like some sort of favoritism. In fields where there are a fairly small number of experts, and where they tend to do a lot of refereeing, this would be a problem, and one that would discourage me from refereeing more if it were required.

Money can be the solution to a lot of these problems. I don’t know why we continue to rely so heavily on traditional publishers who make a killing off of our free labor–authors, reviewers, editors, etc. We could move many of these journals in house, paywall articles for a low cost or otherwise provide subscriptions to universities, and then compensate reviewers. We could also start charging people to submit–even a nominal amount like $20–would cut down on the number of not-as-serious submissions. We’re not talking about a lot of money, but even paying a reviewer $50 would probably address many of these problems.

It really would be great if reviewers could get paid. But I’m not very sympathetic to the idea of charging authors to submit their work. This discipline already favors people who come from affluent backgrounds (it’s far easier for them to attend conferences and network, for example). Having authors pay to submit their work to journals would exacerbate this problem, I think. I myself don’t come from money. I remember when I was in grad school and lived on the cusp of the poverty line. I knew that to be competitive, I should try to have publications before earning my PhD. I succeeded, but if I had to pay for each time that I submitted a manuscript, then I’d have made fewer submissions and I’d probably have at least one less pub before going on the market.

Right now there’s little incentive for people not to submit what is generally unfinished work to journals in hopes of getting helpful comments and, possible, an R&R. That we have a significant number of submitted articles that shouldn’t have been submitted further taxes and already taxed review system.

While I’m sympathetic to the plight of poor graduate students, it would be easy enough for the student’s department to allocate funds for this purpose or for graduate students to come up with a nominal amount of money ($20, for example). The flip-side of things is that when you have people who pay for a service, those people can usually demand certain things from those providing that service (more timely reviews, more constructive comments/feedback, etc.). This strikes me as a win-win.

I agree there are benefits to your idea, such as dissuading people from abusing the system by submitting unfinished work. But I’m still not very sympathetic. I don’t really agree that it would be easy for departments to allocate funds for this purpose for their grad students. As it is, most grad program can barely afford to pay their grad students a living wage. And the department would have to set up some system or committee to decide on certain policies about who should get money, how much money, under what conditions, etc…and then enforce that policy. This is a lot of work and I’m skeptical that many programs would go through the effort. Also, we should remember that there is an enormous number of adjunct philosophers (who in my a experience tend to come from more humble backgrounds than those who tend to land TT gigs right out the gate) who are no longer grad students, who are still interested in publishing work, and who have highly precarious financial situations relative to their full time TT colleagues. They should be borne in mind as well.

Again, I appreciate the concern, but I’m not sure it’s reasonable. How many papers, on average, are these people submitting per year? More than 5? If not (as I suspect), we’re not talking about more than $100 under my scheme.

It’s tempting to try to start a journal just to test this approach. Sadly there are already so many journals out there that the last thing we need right now is another one.

Two quick notes:

There are journals out there right now that do charge per submission – Phil. Imprint is the most famous of them.

I’d also disagree that we don’t need more journals. We certainly don’t need any more regular journals run by huge publishers, e.g. Springer, but we could certainly use more open access journals, of which there are only a few in philosophy (the only I know of are: Phil. Imprint, Ergo, Australasian Journal of Logic, Feminist Philosophy Quarterly, Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy).

From the website of the American Journal of Political Science (equivalent to J Phil or Phil Review):

“Articles are selected for publication in the AJPS on the basis of a double-blind review process. Authors and co-authors of submissions to the AJPS are expected to review manuscripts for the Journal. The AJPS Editor reserves the right to refuse submissions from authors who repeatedly fail to provide reviews for the Journal when invited to do so. Any such submission refusals will be made only after consultation with at least two members of the AJPS Editorial Board.”

American Political Science Review – another high-ranking one – has a very similar clause. It’s not, to my knowledge, universal amongst Pol Sci journals, but obviously not alone.

The upshot of this proposal would be to make it far less likely for me to agree to referee. I get nothing if I do a good job, and I get punished if I do a bad job. That’s a helluva deal.

An alternative would be to have some sort of membership arrangement, at least for tenured faculty: that they can publish in a journal only if they become one of its members, but that this membership requires that they be willing to meet some referee obligations each year. I’ve no idea what negative consequences this system might have — no doubt quite a few — but it at least creates an incentive to referee.

“I get nothing if I do a good job, and I get punished if I do a bad job. That’s a helluva deal.”

This actually sounds fair if you think—and that’s not a wildly implausible view—that refereeing is among your duties. Sure you might be entitled to praise or reward if you do a fantastic job, beyond expectations, but not for doing what you’re expected to do as a member of the profession, especially one who stands to benefit from others cooperating in the same way.

I don’t have full confidence refereeing actually among our duties. And I worry too that the system might deter those who think it’s not. But I find the proposal appealing.

I think refereeing is a duty, but refereeing in a fair and cooperative system. I don’t have a duty to referee under just any sort of terms.

Fair enough, but how are the proposed terms less fair than the current system? If it would contribute to a more effective review process it could in principle be better for everyone doing their fair share, albeit not for free riders (that’s the point). But maybe I’m missing something.

Thanks to Elizabeth Hannon for opening up this important discussion. I do worry that penalizing reviewers in the way proposed would risk overlooking and perhaps reinforcing the increasing institutional pressures under which academics, especially junior academics, are put. I’m keen on Tom’s suggestion that reviewers be publicly acknowledged such as by publishing their names alongside the authors’. Appreciating that it’s only a start in remodeling the value structures of publishing, the Public Philosophy Journal practices this, for instance. The PPJ also regards Public Holistic Responses, or reviewer responses published alongside a formatively peer reviewed, final work, as valuable publications in their own right that reviewers may include in their CVs and to which committees may consider giving more weight in T&P reviews.

I have just quickly made myself a list of journals for which I have refereed over the last few years without ever having submitted to them. I came up with twelve such journals. With regard to most of them, the option of being able to submit to them in the future is of little value to me. I fear that the proposed system of disincentives, if widely adopted, would turn refereeing into a quid pro quo thing in the minds of most academics. As such, it would benefit some top journals (I definitely want to keep the option of submitting to BJPS in the future), but work to the disadvantage of others. As Sergio Tenenbaum points out in his comment, the proposal can only work if (repeatedly?) declining invitations to review is punished as well. So people would reserve their refereeing time for journals that they are interested in submitting to, which would in my opinion be a bad thing. More generally, I think that refereeing is a duty and that it will only work if academics are intrinsically motivated to do it (and do it well). Bringing in extrinsic factors to “support” the intrinsic motivations usually tends to undermine the latter.

Crazy idea: publish reviews in a digital annex alongside the papers. That way you get some name recognition for reviewing, people can tell whether you were reasonable and sufficiently critical (without being a jerk), and you can show your dean when the time comes to document your contribution to the field.

I put a lot of effort into my referee reports, and try to provide both critical and helpful comments. I tend to do this if I recommend publication or not. But, they are not in anything like publishable form, and I wouldn’t want them published in the form I send them. Because I already spend a lot of time doing this, and it would take a lot more time to make them in anything like publishable form, this idea would make me much less likely to agree to referee. This would be even more the case if the benefit from such a ‘publication’ was small, as I expect it would be, but even if not, turning a report into even a minimally publishable version would add enough work, taking me away from my own projects and teaching, that it would be almost completely unattractive to me.

Like Michael Cholbi mentioned above, Publons allows one to get recognition for reviewing papers. BJPS is on there as well: https://publons.com/journal/3268/british-journal-for-the-philosophy-of-science

Ethics publishes a list of its reviewers once a year I believe.

To my way of thinking, the term “free-loader” is not correctly applied in this discussion. Surely it is the journals, and not the authors or referees, no matter how tardy in their revisions or their reports, who are free-loading here. The authors and the referees both work for free, ultimately for the financial benefit of the journal.

Consider the following allegory, which I find highly relevant to such discussions (my earlier comments to this effect seem not to have been posted for some reason; please post only this one, if possible).

I have a friend, let’s call him Horace, who owns an art gallery. He has convinced all the artists in the city to give him their art to sell in his gallery. They sign over ownership in their works, and he sells them. But Horace keeps all the money; the artists get nothing. Horace has also cleverly arranged that the artist perform unpaid cleaning tasks in his gallery. They wash the windows, sweep the floors and clean the restrooms, all for free. They do this because they want their art to gain a wide exposure. Horace himself does nothing except enjoy the art and collect the money.

Recently, Horace received a profoundly beautiful, moving piece from a particular artist, Hortensia, known for her penetrating, thoughtful works. The problem is that last week, Hortensia missed a few spots on the window in her cleaning task. And last month she was late several times to her assigned cleaning duty. Should Horace still accept her work?

The other gallery owners said, No! Something needs to be done about those free-loading artists, who don’t do their assigned cleaning tasks. How can the system continue if the artists don’t continue to keep the gallery clean?

What I told my friend Horace is that the whole system is flawed. The gallery owners should simply pay for the cleaning services that they require. And more importantly, the artists should stop so easily signing away ownership in their works.

To be frank, I find it ludicrous for a journal or even a journal editor to complain about “free-loading” referees. If the journals want expert advice on what to publish, let them pay for it. They certainly have the resources. It is surely the journals themselves, rather than the authors or referees, who are free-loading.

(Just to be clear, for the record, I myself do plenty of refereeing, and I estimate that I am asked to referee papers several dozen times per year, although I can accept only a fraction of that, but I do. I wish I had more time to referee more papers, since oftentimes, they are very good.)

Sorry, I had meant, “free-rider,” as in the original post, rather than “free-loader,” throughout.

At least as I read it, there is a significant dissimilarity between your allegory and journals. In your allegory, you imply that Horace is managing the art gallery, and thus, when artists do not clean, they are inconveniencing him. To be more accurate, the artists should also manage the gallery, and thus, when artists do not clean, they are only inconveniencing their fellow artists, not Horace, who remains passive and collects the checks regardless.

When referees don’t respond, they are not “sticking it to me Man.” They are just being rude to their fellow academics. Of course, there could be a different systems where referees were paid or where journals were co-ops. Maybe those are better systems, but the fact that systemic improvement is possible is not an argument against incremental change.

Well, if the gallery isn’t clean, then it will have fewer customers viewing the art, which prevents the artist’s work from being seen, and this is their main interest in the gallery. But also, the referees and author’s are not ordinarily considered “managers” of the journals to which they contribute papers and referees. So I’m not sure I agree with your objection. But even so, it seems a minor objection, not a “significant” difference.

The allegory is meant in part to bring to the surface the question of whether the journals provide any value-added service at all. My view is that the current academic publishing system is seriously broken. And for an editor to complain about laggard reviewers, who are working for free, completely without any benefit or even acknowledgement, is simply out of touch, showing a lack of perspective of what their role should be in the research community. The society should stop using the BJPS as a means of fund-raising, and they should instead organize their journal publishing based on a model that works in the interest of the researchers in the profession, which is I assume a central part of the mission of the society. It seems obvious that if journals are making money, then referees should be paid. Such a plan would solve essentially all the problems that are mentioned in the post, and have many other benefits.

I’m appalled by the suggestion that once I’ve agreed to participate in the journal publishing system, I’m no longer allowed to take a holiday (or I’ll risk sanction if I do.) Performing free labour for publishers is one thing. Signing away my rights to take a vacation is another. (And for those of us who have substantial caring responsibilities, taking the paid time off that our contracts allow is often a key part of our childcare strategy.)

Jftr: I’ve refereed 22 times in the last 12 months. (You can check my record on Publons.) While that’s probably not as many as some people, I don’t think I’m slacking here.

[These are posting all out of order–apologies]

Common concerns:

1. The most important point is that the idea here isn’t to apply a rule mechanically (for example, being banned for being one day late). The reviewer would also receive explicit warnings so this wouldn’t come out of the blue. Like every other aspect of peer review, this proposal isn’t without its drawbacks. Nonetheless, it may be that this is an imperfect solution to a much worse (and very common) problem.

2. We are not proposing any punishments for those who simply decline to review in the first place (at least, so long as they actually communicate this rather than leaving the invitation hanging—and declining here is only ever a matter of clicking a link in an email).

3. We are not asking for the intimate details of reviewers’ lives. While it’s not unknown for us to receive tearful emails from authors and reviewers in terrible situations, we do not expect reviewers to bare all; it’s simply not our business. We will take at face value your reasons for any delay or for withdrawing from a review; there’s no need to elaborate or provide ‘proof’ (whatever that might be). We just ask that reviewers make contact!

4. The aim of this proposal is to promote timeliness. It would be only the most exceptional and egregious cases where the content of the report itself might warrant an embargo—and even then only in combination with tardiness.

5. One worry that has been expressed is that people will be more inclined to turn down requests to review. It’s hard to know what to make of this, unless one is really committed to (a) the ability to walk away from a promise to review a paper while (b) not communicating this decision with the editors. But anyway: One of the reasons we’re proposing this is because we actually want people to turn us down if they can’t realistically meet the deadline. And anyone who has reviewed for us in the past and found themselves in need of a reasonable extension will know that we always accommodate this.

6. Another worry is that the proposal is disproportionally harmful to early career researchers. Our internal rating system for reviewers suggests that ECRs are not the problem here.

7. The publishing industry is evil and we oughtn’t cooperate with it: (a) I guess this might eventually harm the publisher, but it will definitely harm the authors and editors (your equally unremunerated colleagues) in the meantime; (b) not all publishers are equal and the BJPS’s income supports the British Society for the Philosophy of Science, who funnel that money right back into the philosophy of science community, via PhD and conference grants; (c) if these reasons don’t motivate you, fine—but then please don’t accept invitations to referee!

Thanks to everyone, here and elsewhere, for their feedback—it’s been really helpful. I thought I’d add some clarifications to the original post and respond to some of the alternative suggestions. Some concerns stem, I think, from the thought that we’re concerned with a wider set of behaviours than is the case. Some alternative suggestions can’t be accommodated for ethical or practical reasons. I’m sure I haven’t covered every issue here (despite the length of this reply!), and so very happy to receive more feedback.

So, there seems to be an obvious tension between the claim that the BJPS can’t pay its reviewers (1) and the claim that it puts money back into the Philosophy of Science community (7).

Presumably one way the journal could put money back into the community would be to pay its reviewers. (As things stand, it’s effectively asking its authors and reviewers to subsidize the other activities ot chooses to fund through their free labour. That may be a reasonable thing to do, but if that’s what the arrangement is, asking people to prioritize their contributions to what is, in effect, a professional self-help scheme over their commitments to employers, families, etc seems a bit ungracious.)

Again, Bill, all we’re asking is for referees to make good on their commitments – if someone agrees to referee a paper then fails to meet the deadline and fails to respond to reminders or fails to give a reason … then it doesn’t seem entirely unreasonable that the journal might impose some form of sanction. As for payment, speaking for myself, I’d rather the income from the journal supported PhD students and workshops than be used to subsidise what I’ve always felt should be part of ones duty to the profession and colleagues!

Hi Steven

If the proposal is (just) to sanction people who consistently/persistently fail to send in reports on time, don’t respond to emails and so on, then I don’t really have any objection. (To be honest, I’d assumed that, to the extent that journal editors and editorial assistants are human beings, this sort of thing tends to happen on an informal level anyway. Making it formal might have the advantage – if it is an advantage – of making sure that these kinds of informal sanctions are applied consistently and that people don’t skate for bad behavior because of their perceived star status. So there’s at least that much to be said in favor of the proposal – provided that it can be consistently applied.)

That said it seemed as though in the initial post, the proposal was to sanction a wider range of behavior including not responding promptly to invitations to review, asking for extra time because of vacations and so on. If it wasn’t clear from the context that that was what I was objecting to, I hope it’s clearer now. (As to not replying to to invitations to review: I know of at least one journal where the editor’s policy is to treat people’s non-responses as defaulting to agreements to review, as I found out when I found in my spam folder a terse ‘reminder’ that a review for a paper that I had never heard of before was now a month overdue. While I don’t imagine that as well-run an outfit as the BJPS would ever countenance doing something like this, I think that when we’re discussing general norms for the field it’s worth bearing in mind the possibility of bad behavior on both sides of the editor’s desk.)

As far as the question of whether referees should be paid is concerned, I’m inclined to agree with you that I’d rather see refereeing as involving a gift economy rather than a monetary one. But I think it’s worth entering three caveats here. The first is a plea for honesty in argumentation. I think there’s a big difference between asking members of the profession to support the BJPS via their free labor because there’s no practical way of remunerating them, and asking them to do so because you’re choosing to spend your money on other things. (I’m inclined to think, for example, that this is OK for a specialist journal like the BJPS with a relatively closed community of reviewers and authors, who can be expected to support the purposes to which the money is put; but it’s less obvious that it would be OK for other journals with other remits.) The second thing is that I think a lot depends on what those other purposes are: providing a stipend for a graduate student is one thing; paying the travel expenses for a big name whose work already gets plenty of exposure to be a keynote at a closed workshop is another. And finally, and contra a point David Wallace has made downthread, I think that if we are going to maintain the gift economy ethos, we can’t simply shunt the question of who is profiting from our labor off to one side. While it’s true that when I’m refereeing a paper I’m engaging in a gift economy exchange with a community of scholars, it’s *also* true – special and admirable cases like Ergo and JESP aside – that I’m also maintaining the value of a commercial investment on the part of the journal’s publisher. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to see that as affecting the normative structure of the arrangement, and thus the expectations that it’s reasonable for editors and indeed authors to have.

And now I’ll get back to that referee’s report I was working on (don’t worry – so far I’ve only had the paper a week.)

I was a poor graduate student way back 2 years ago. It was rough, indeed. I remember eating roman for a month so I could go to Europe for a conference. Notwithstanding, I think it is just nonsense that grad students couldn’t afford say 20-100 dollars a year to submit papers. How much do grad students spend of Starbucks and alcohol? Besides, we can always do a graduated system (and I think we should) where your submission cost is based on your yearly salary. Paying referees is a completely do-able solution, and really should at least be tried. Maybe when I get tenure I will try to start one, but it would be much better to start it with a journal that already has a solid reputation. I think Ergo would be a good option, given its format.

I am not keen on the idea of punishing folks for not responding to invitations to review. On an average day, I receive far too many unsolicited emails to read and respond to them all. I try to keep an eye out for review requests as best I can, and I catch most of them and reply in a timely fashion, but sometimes they slip past my notice or get overtaken by other incoming email. I suspect I am not alone in struggling to keep up in email, and indeed that some are worse off than I am in that respect. In this and many other parts of professional life, I think we have to temper our expectations about how people deal with unsolicited email generally. (Once folks have accepted an invitation and failed to deliver is another matter.)

J.D. Hamkins makes a good point above. According to this article, Oxford University Press, of which BJPS is a part, made a net profit of 94.1 million pounds in 2013/14. That’s about $125 million US today. It’s a bit odd to hear some *volunteers* referred to as “free-riders” in this system, whatever their faults.

https://www.thebookseller.com/news/oup-sales-profit-down-306267

That said, Hannon’s complaints 2-4 are worth considering. However, complaint 1 is not. We have no particular obligation to respond to unsolicited requests in any particular time frame (as others have suggested). It is nice to do, of course, but not required. Journals should take it upon themselves to move on if they don’t hear back within a certain number of days.

So far as I can see, the issue of journal publishers’ profits is neither here nor there.

An academic journal is – in effect – a collective enterprise, run by academics for academics. The editorial board of a journal then contracts with a publisher, who sorts out the logistical side of the journal – copyediting, printing, web services etc – in exchange for getting to collect the subscription fees for the journal. No publisher I know has any interest in moving to a pay-the-referees arrangement, and no journal editorial board has leverage to achieve that. (At the very least, no humanities-journal editorial board has – BJPS will be a rounding error in OUP’s journal budget, which I think is dominated by medical-science journals.)

If you think OUP makes excessive profits and there is a better deal to be had, lobby the board of BJPS to resign en masse and move (and probably rename) the journal to a different publishing arrangement, either with a publisher you like better or on some kind of open-access system. But doing so, whatever its other virtues or vices, won’t solve the problem that Beth Hannon is raising.

Hi David,

We seem to have moved quickly from my admittedly snarky claim that we not ignore the money when discussing referee incentives/disincentives to claims about “excessive profits” (not my words) and en masse resignations. My snark likely contributed, and I’m sorry about that. In any event, I think there is room for a more subtle and thoroughgoing discussion here.

For instance, the construal you present of academic publishing is reasonable, but not the only reasonable construal. I think Hamkins’s has something going for it, though I wouldn’t go as far as he does. I also think there’s a reasonable discussion to be had about whether a journal publisher’s interests are only financial. There are a lot of other issues to consider, too. In any event, Oxford UP seems to deny that its interests are solely financial:

“At Oxford Journals, we share the values of our society partners because we are part of the scholarly community. Our mission is to ensure that high-quality research is as widely circulated as possible in order to support education, research, and scholarship. ”

…

“As a university press, we have no shareholders to satisfy. This means that we can devote ourselves entirely to our society partners and work solely on your behalf, returning any profit to the academic community through journals reinvestment and society payment.”

https://academic.oup.com/journals/pages/societies/our_values

I know how marketing works, and I know OUP is not against making money. I don’t object to either. But perhaps pay-for-referees is a journal innovation they’d consider. We’d have to ask, and back up our ask with good reasons. Is OUP unusual? Maybe. Still, whether pay would solve some of the problems we’re having is a conversation worth having. And the issue of profit has something to do with whether journal publishers can reasonably afford to consider such an innovation.

On Elizabeth Hannon’s suggested alternative 4: “Good reviewers could have their own papers ‘fast tracked’ through the peer review system.” Maybe not ‘fast tracking’, but are there are some ways in which they might be able to get ‘priority’ status? For example when good reviewers submit an article they get to the top of the pile for desk consideration (or a guaranteed maximum number of days it would take for a desk reply); they get priority for a final decision when the reviews come back (I recently waited over a month for a editorial decision on an article where after the reviews had come back); maybe they are more likely to have their work sent to other ‘good reviewers’?

I glanced through the comments and the OP. I’ve elsewhere suggested submission fees by which to pay referees. Punishing referees is also an option I guess, although I’m not sure why anyone would agree to referee if at best they’ll be punished. What the system needs is positive reinforcement, not just punishment. Unfortunately, there is little incentive to referee. We’re not paid to referee and hiring committees and tenure boards count refereeing for little or nothing. So, why should we referee? What’s in it for us?

The current referee system was fine decades ago when the job market was comparatively good, article submissions were orders of magnitude less, and academics were not so overworked. However, in the modern age of 500 applicants per TT job, 60 hour work weeks, adjunct labor, short-term contracts, and increasingly worse pay the good will just isn’t there. When you have to publish enough articles for tenure 20 years ago just to get a starter job today (if you’re lucky), you simply cannot afford to referee.

There can be good will in a system that treats academics with respect, provides secure jobs, and doesn’t expect 60 hour work weeks, otherwise there cannot. Fixing the problem requires collective action. What should be done is that enough academics must collectively refuse to referee until demands are met. This is the weakness in the current system. It would be very easy to collapse it entirely if enough of us refused to referee. So, if we bind together, we can change the system. What do we want? Pay?

I think given the horrible job market, we could all use jobs. So, I suggest that referees should be paid, and paid handsomely. This would benefit journals and authors as well, as now referees would have incentive to return reports in a timely manner, i.e. money. All it takes is collective action! The publishers will figure out a way to pay us if they realize it’s the only way to remain in business and not go bankrupt. Are we tired of giving the publishers free labor? If so, let’s stop. We’re the experts. There aren’t any others. The publishers can’t replace us with robots or computers. Our jobs can’t be outsourced to China. We hold the power, as without us they can’t determine what to publish.

I suspect academics are far too milquetoast to take any of the actions that would be required to improve the system. If so, the complaining is getting old.

I’m pretty confident I’m paid to referee. Refereeing is part of being research-active, along with writing letters of reference, serving on grant committees, attending and organizing conferences, and writing papers. I agree that the performance-review structure of academia is very focused on the last of these and doesn’t pay attention to the rest, but that’s a different matter. (I’m much less confident that postdocs are paid to referee; I think deciding that “you simply cannot afford to referee” at that career stage is fair enough.

A significant portion (if not the majority) of refereeing is done by graduate students, postdocs, adjuncts, unemployed philosophers, and similar. As a graduate student, I reviewed multiple articles for top journals. As an unemployed PhD, I was asked to do even more refereeing for top journals. I think I reviewed 10 articles before refusing to do more. If just those who are not paid, refused to referee, that would collapse the journal system. So, if we want to change the way the system works, all it takes is collective action. We must strike and make demands. Anyway, I for one will not referee articles without pay.

And David, you claim you’re paid to referee, but isn’t that just de jure? Would anything happen to you if you never refereed? What if instead of refereeing, you published more papers or applied for more grants? Wouldn’t that benefit you more? If refereeing doesn’t help your career advance and there are no negatives to you not refereeing, I question whether you are in fact paid to referee vs. refereeing just being given some lip service in a contract somewhere.

Two suggestions on referees (slightly at right angles to the question of how to deal with unprofessional behavior from referees, but relevant to Elizabeth Hannon’s original observation about the difficulty of finding referees):

1) in the sciences, the standard way to find competent specialist referees is to ask the author(s) of the article being refereed: indeed, recommending referees is part of the process of article submission. That would seem to save a lot of time if we adopted it in philosophy: the editor is normally not an expert on a given paper’s topic; the author (almost certainly!) is. Those suggestions don’t have to be followed, of course, but at the very least asking authors to suggest 3-4 referees (who are not their students, colleagues, supervisors or lovers) would provide a substantial extra resource.

2) Anecdotally, I gather that concerns about anonymity are a significant problem for finding referees: people refuse to referee a paper when they recognize who it’s by, either because they genuinely feel it’s inappropriate or (more cynically) because it’s an excuse to say no. And particularly in small fields, very often you are going to recognize a paper’s author. I think we would do well to reorientate anonymity from a substantive to a procedural constraint: papers should be anonymized, and referees should be enjoined not intentionally to seek out who the author is, but the contingent fact that they recognize the author shouldn’t be a reason to say know. We can still address the more serious conflict-of-interest issues directly: don’t referee papers by your students, colleagues, supervisor(s) or lover(s). (In fact, triple-blind refereeing actually gets in the way of policing those conflicts).

The natural response is that both suggestions harm the equity of the refereeing process, and indeed go somewhat against the trend of recent editorial policy. I think this is seriously overblown as a concern (the sciences manage perfectly well without even double-blind refereeing, and with authors recommending referees) but for the sake of argument let’s stipulate that both (1) and (2) increase the unfairness of the system. That doesn’t suffice to reject them. Equity is an important virtue in the editorial process but it is not the only one; it shouldn’t be given infinite weight in comparison with efficiency. And given the large and increasing strain on our system, as attested to by pretty much anyone who’s acting as a journal editor these days, there is room to consider whether we should be erring a bit more on the side of efficiency – especially as a highly inefficient and capricious system is itself a major generator of inequity.

This idea is not good. If such punishment were instituted, it would be even more difficult to find referees accepting requests to referee, for there is always a risk that you may not submit the report on time, or the report “might be meagre” or whatever, and so it would be better to decline the invitation and keep the right to submit papers to that journal. There is already little incentive to referee papers. And this would add a disincentive.

I understand the frustration of Elizabeth Hannon, but punishing is almost never the most effective thing to do.

This idea is not good. If such punishment were instituted, it would be even more difficult to find referees accepting requests to referee, for there is always a risk that you may not submit the report on time, or the report “might be meagre” or whatever, and so it would be better to decline the invitation and keep the right to submit papers to that journal. There is already little incentive to referee papers. And this would add a disincentive.

I understand the frustration of Elizabeth Hannon, but punishing is almost never the most effective thing to do.

‘That they could be applied there’ – that’s not very clear. I mean, ‘That they could be applied by at least some journals’.

I worry about punitive measures like this. As other commentators have noted as well, I think they’re likely to have unintended consequences. Like several other posters, the biggest one I see is that people will just become even more likely to just decline invitations to review since they’ll worry about being punished for even agreeing. And one of the main things holding up reviews is the inability to find competent reviewers who’ll agree do to it! I’ve twice had journals email me to tell me that it took two or so months to even begin a review process because they’d had trouble finding referees. Instead of going for a radical and punitive solution, I think we ought to think about instituting a number of small changes that might, when put together, have a big cumulative impact. Wallace’s suggestion that submitters suggest a few referees (or at least have the option of doing so) is a good one since it would help with the problem of finding referees. Surprenant’s suggestions that submitters pay a nominal fee and that perhaps that referees get paid are also good. People do often send half-baked work out in the hopes of getting feedback or maybe getting lucky, and a fee would discourage that. Getting paid, is, I’ve found, a pretty good incentive even if the amount is small. It changes the way you think about what you’re doing. When one isn’t paid for a service it’s all too easy to see it as a favor or as some supererogatory action; this makes it very easy to justify not doing the job well to oneself. The ugly truth is volunteers often do their jobs pretty badly in a lot of fields. But when one is paid it’s much harder to make those mental moves that justify such behavior.

I’ve a few other suggestions that I think would lead to improvement: 1. Journals ought to provide clear guidelines for referees. What are the criteria you’re looking for? What questions should I ask myself as a referee while reading this? What do you as an editor need to know in making your decisions? I’ve found that these are pretty helpful for me as a referee and lead to more detailed comments and better decisions. This would do a lot to make reports more useful I think. 2. Journal editors should take the time to personally email referees with reminders. It’s a lot harder to ignore an email from a person. This does make a difference even if it might be mildly uncomfortable for the editor. 3. Why not have it as a matter of policy that if one publishes in a journal one is committed to doing a review for them in the future and doing so in a timely fashion? Journals could have authors sign this agreement at the same time they sign the copyright or other forms. As with paying someone, I think this arrangement would also do away with the “I’m doing a nice thing here so you can’t complain if I halfass it” mindset that’s responsible for so much bad behavior on the part of referees.

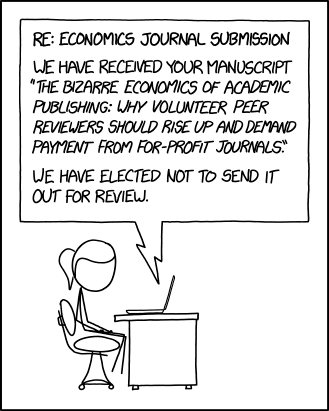

‘Bit late but relevant comic: