Women in Philosophy Journals: New Data

There are new findings on the presence of women in academic philosophy journals:

- Though approximately 25% of philosophy faculty in the United States are women, only 14-16% of the articles that appear in the discipline’s top journals are by women.

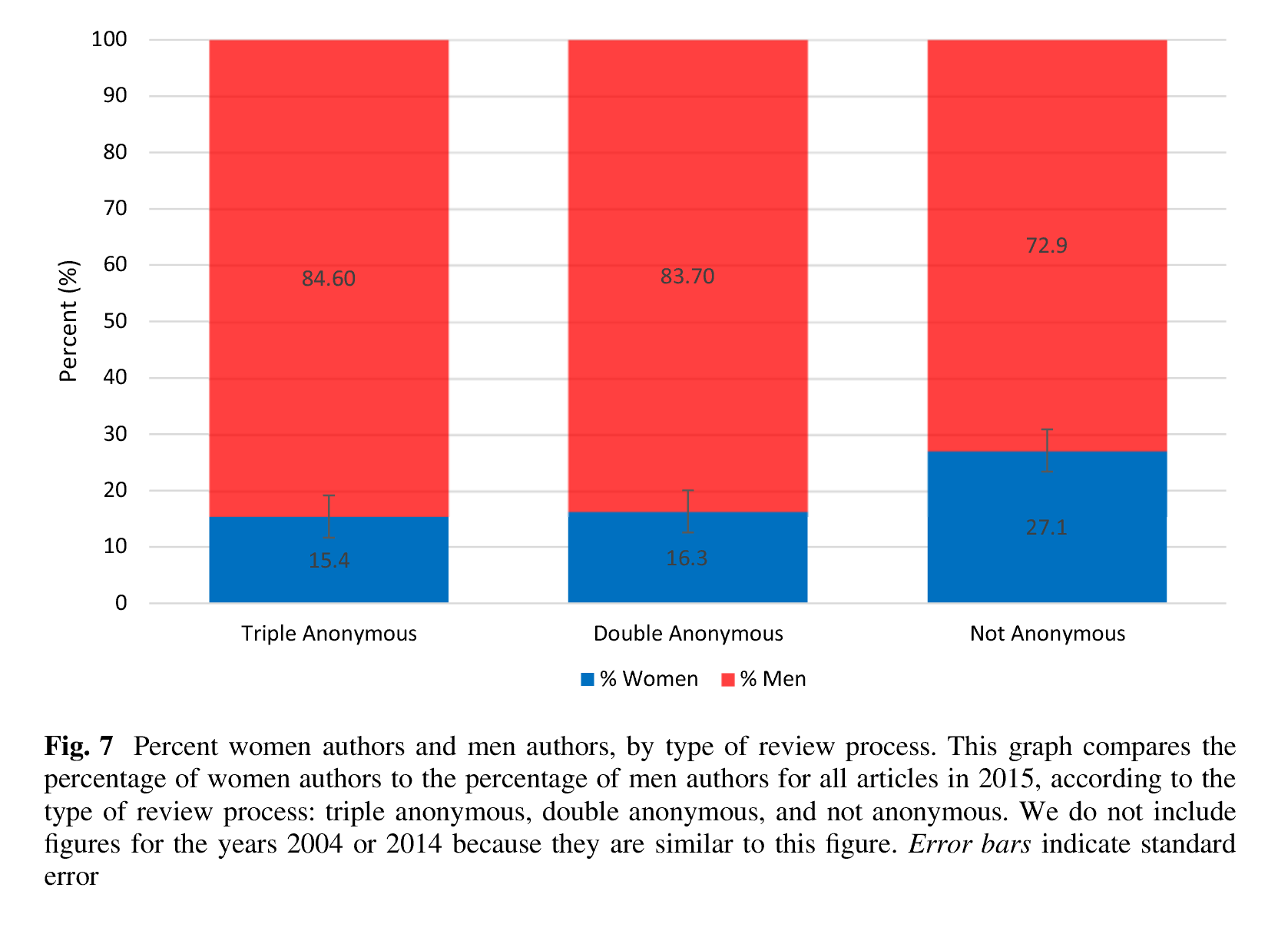

- Journals which do not use anonymous review seem to have a higher percentage of women authors than journals which do.

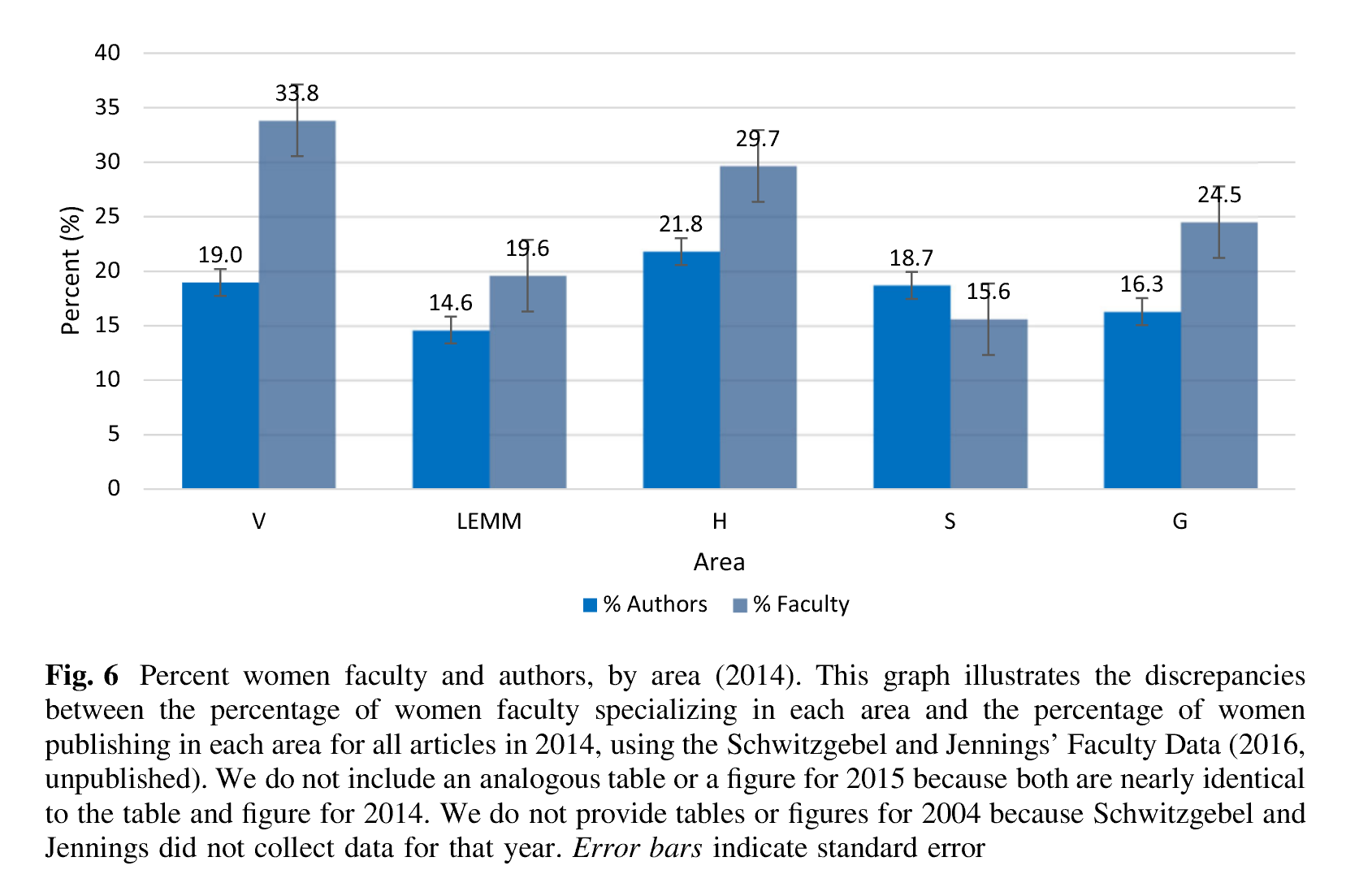

- The discrepancy between the percentages of women authors and women faculty varies across different areas of philosophy.

These are among the conclusions reported in “New data on the representation of women in philosophy journals: 2004–2015” by Isaac Wilhelm (Rutgers), Sherri Lynn Conklin (UC Santa Barbara), and Nicole Hassoun (Binghamton), forthcoming in Philosophical Studies.

Here is a figure from the article listing the journals included in the study and showing the percentage of contributions by women authors:

from “New data on the representation of women in philosophy journals: 2004–2015” by Wilhelm, Conklin, and Hassoun

The next graph shows the discrepancy in subfields between the percentage of women working in them and the percentage of journal articles by women in them (note: if you are having trouble seeing the entire image, you should be able to click on it to open it in its own tab):

- encouraging authors to read and cite “all the current literature relevant to one’s area of research” (attributed to Marcus Arvan).

- having journals “include statements in their instructions for contributors that encourage authors to consider whether they have sought out all the literature, relevant to their topic, that may have been published by women or other individuals from underrepresented groups,” as the Journal of the American Philosophical Association does.

- applying a “Bechdel Test” to philosophy papers: “A paper that passes this Bechdel Test would cite publications by at least two women philosophers, where at least one of the cited publications is thoughtfully interrogated, and at least one is cited because it discusses the woman’s original work or the work of another woman (and not because she discusses a male philosopher’s work).” (attributed to Helen De Cruz and Eric Schwitzgebel).

- having editors solicit submissions from women.

One question not addressed in this research, but which I think would be useful to learn the answer to, is whether papers by women fare better in the reviewing process when anonymously reviewed by referees who are women than when anonymously reviewed by referees who are men. Looking into that question might tell us something interesting about gender and philosophical knowledge, and also let us know whether soliciting more women as referees could help address publishing disparities.

I haven’t clicked through to the paper itself, but I am confused about Fig 3: The key and the caption seem to contradict one another. The key indicated 2004 is light blue and the caption that it is dark blue. Which is which?

Thanks for catching that. I believe the legend is correct, and the caption is not. The caption for Figure 3 should read: “Percent women authors of all articles, by journal. This graph illustrates the percentage of women authors for each journal in the years 2004 (light blue, top bars) and 2014/2015 (dark blue, bottom bars).”

This is helpful. I thank the authors. But, as Justin notes, it leaves some important questions unanswered. Is there any data (or plans to gather data) about what percentage of submissions in these journals are women? I would like to know whether it’s that women’s papers are less likely to be accepted or that women are less likely to submit to these journals. Or, if it’s both, how much of the problem is due to one rather than the other. Moreover, I would like to know whether triple-blind review decreases the number of submissions from women or decreases the likelihood that their submission will be accepted. I know from my own editorial experience that sometimes women are underrepresented in the submissions received and, thus, underrepresented in the journal even when the review process is equally likely to result in acceptance whether the submission is by a man or a woman. This doesn’t mean that there isn’t a problem. But it does mean that the problem doesn’t lie with the review process in these instances. In these instances, the problem lies with perhaps the scope of the journal, the journal’s outreach (or lack there of), or with other problems within the profession.

“One explanation for why so few women are published in philosophy might be that very few women submit their work (Huber and Weisberg 2014; Weinberg 2014; Philosophical Review 2016). Data released by the philosophy journals Dialectica, Ergo, and The Philosophical Review, which suggest that women account for only 12–16% of submissions, supports this hypothesis. The explanation might be that women simply produce less written work. But alternatively, it might be that women are less likely to submit to high ranking journals, or to philosophy journals in general. Women might instead submit to journals in related disciplines such as religious studies, psychology, or history. More data on academic paper submission is needed to fully understand this phenomenon.”

A few of us are currently collection more data that will help answer some of these questions, thanks for the helpful comments/suggestions!

It looks like non-anonymous review is biased in favor of accepting papers written by women. (I’m assuming here that anonymous review does a good job of eliminating any bias for or against accepting papers written by women.) Do people think that’s ok? There’s clearly a consensus (at least in the comments section of this blog) that it’s permissible to have bias favoring women in hiring, but my sense is that there is less consensus in the case of journal publications.

I think (but am far from sure that) the thought is this: women already suffer a disadvantage from anti-woman implicit bias. Consequently, equity demands that we counter that bias with a pro-woman explicit bias.

Obviously, it’s hard to know if one bias is proportionate to another, and, because there are interesting criticisms of the very notion of implicit bias, some people will not see it as the countering of one bias against another, but rather as simply unjustified bias in favor of women.

However, assuming implicit bias is real, and assuming it’s leveled more against female writers than it is against male writers, do you think there’s an obligation to counter it in some way? And if so, is having an explicitly pro-female bias the right way to do it?

“women already suffer a disadvantage from anti-woman implicit bias”

one, this is under dispute by the very data being discussed — and there’s an even stronger bias favoring women hires in certain STEM areas. http://www.economist.com/news/science-and-technology/21648632-recruitment-academic-scientists-may-be-skewed-surprising-way-unfairer

two, this is an empirical claim I’m not sure philosophers unilaterally have the methodology to discuss properly anyway — at the very least not to claim some kind of consensus on the issue

three, since when is it good epistemology to adjust a whole set of decisions on the possibility that party A might be biased, when by doing so you risk unfairly favoring party B as a consequence? the responsible thing seems like agnosticism.

Hi Alfred,

In case it wasn’t clear, I wasn’t myself taking a stand on this issue. I try to avoid taking stands.

Regarding your third point, it’s a good question. So let me just ask you this: imagine you had expertise in the subject matter, and were convinced that there was implicit bias that lowered female applicants’ chances of getting their work published. If that happened, what should the right response be?

The data do not indicate that non-anonymous review processes are biased towards women authors. After all, journals with non-anonymous review policies are not publishing women authors at a rate disproportionate to their presence in the field of philosophy. Nor does it suggest that non-anonmyous review necessarily goes hand in hand with inviting more underrepresented philosophers to submit articles. There are journals like Social Philosophy & Policy that do invitation-only and non-anonymous review that have abysmal rates of publishing women (stay tuned for more news on this). The authors of the article under discussion suggest that implicit bias and dodgy pseudo-anonymous review processes may be to blame. From p. 19:

“There are several possible reasons why women do worse in journals that review anonymously. First, the majority of the reviewers at these journals are probably men (Hassoun and Conklin 2015). It is possible that men and women have different opinions on what does and does not constitute important or interesting philosophy (Dotson 2012). Second, biases against women may be affecting theprocess of anonymous review, despite the intentions of all involved (Lee andSchunn 2010; De Cruz 2014a). Even when journals try to keep author identities hidden, cues like the article’s written style, its theme, and its similarity toconference presentations of which the reviewers may be aware could still reveal theidentities of the authors (Rosenblatt and Kirk 1981). Moreover, there are some reports that reviewers seek out the identity of the author through the use of Google (Brogaard 2012). It is also worth noting that some journals have built-in procedures to partially circumvent their otherwise anonymous review processes (Lee andSchunn 2010). In the final step of the review process at Ethics, for example, the editors hold a vote to decide whether an article should be published or not, at which point two of the editors are aware of the identity of the author.22 As one Editorial Board member explained, associate editors can also invite submissions, thereby circumventing an initial screening by the editor, and guaranteeing that the manuscript will be sent to external reviewers (Author’s personal correspondence:withheld for anonymity). Practices like these, which may occur in other journals,could make it harder for women to publish. In general, such practices may help well-connected authors—who are overwhelmingly men —to subvert the standarddouble or triple anonymous review process.”

This passage is kind of ridiculous though. It suggests that, if women are underrepresented in journals that practice anonymous review, it might be because people are able to guess the gender of the author despite anonymity. But the data analyzed in the article suggests that, when reviewers/editors know the gender of the author, women are not underrepresented and may even be overrepresented. Indeed, despite what you say, it’s not clear that women are not overrepresented in journals that don’t practice anonymous review, at least the 2 that were analyzed in the paper. Apparently, when the journals in question are analyzed separately, women are overrepresented but the difference isn’t significant. However, just by eyeballing the error bar in figure 7, it’s not clear that it’s still the case when you lump together the 2 journals that don’t practice anonymous review. (I may have missed something about this in the discussion though.) Moreover, this figure just show the results for 2015, whereas in table 4 (which presents the analysis disaggregated by journal) the data for 2014 and 2015 are lumped together. I’d be curious to know whether the difference really isn’t significant for 2015 and, more importantly, whether it’s significant when you combine the data for 2014 and 2015, which seems like the natural thing to do and is what the authors did when they analyzed journals separately. It may be that, as you say, there are journals like Social Philosophy & Policy which don’t practice anonymous review in which women are underrepresented, but they are not discussed in that paper.

Further data and analysis is definitely important. Fortunately, we now have access to a huge proportion of the JSTOR database so we should have a much better sense for what is going on soon!

I doubt there is a consensus about that. I for one don’t think that it’s permissible or, at least, I have never seen any convincing argument in favor of that view. I know a lot of people, both men and women, who think the same thing, but few of them would ever say that publicly. This might explain the appearance of a consensus, but it doesn’t mean there really is one, not even here.

The data say nothing at all about whether non-anonymous review is biased in favour of women, or about whether anonymous review is a harder hurdle for women to pass. To establish *anything at all* about these matters one would need info on the percentage of submissions to these journals that come from women. I would hate anyone to look at these figures and think ‘it’s impossible for women to publish in Mind’, when in fact one of the main problems may be that women just aren’t submitting papers to Mind in the first place, perhaps because they think it’s impossible to publish there.

Indeed, the authors themselves point out that the data that they do have on submissions support Mary Leng’s hypothesis:

“One explanation for why so few women are published in philosophy might be that very few women submit their work (Huber and Weisberg 2014; Weinberg 2014; Philosophical Review 2016). Data released by the philosophy journals Dialectica, Ergo, and The Philosophical Review, which suggest that women account for only 12–16% of submissions, supports this hypothesis.”

At the Canadian Journal of Philosophy, somewhere around 15-20% (depending on the year) of our submissions are by women.

Isn’t the entire point of blind-review to prevent bias? Don’t tell me that because blind review doesn’t yield politically desired outcomes we are going to abandon it in favor of “good bias.”

The idea would be to publish more articles by women in philosophy journals, given how few articles by women are currently published in philosophy journals. The underlying assumption here is that this is important enough to be worth actually doing. So, sure, there could be such a thing as good “bias,” for those who prefer to use that word.

What’s the problem — except for those who don’t care enough about the underrepresentation of women in philosophy and in philosophy journals to support taking measures to directly address the issue? In any case, what’s the worst that could happen if good “bias” raised the number of published articles by women roughly, say, 10 percent? Why begrudge that lost 10 percent when at least 70 percent of articles published in philosophy journals still would be by white men? Why must the philosophy profession at this historical moment suddenly prioritize a certain conception of bias-free fairness?

I like knowing that the papers I read were published on their merits and not due to some other arbitrary factor. It gives me a certain confidence before even reading the paper that the paper deserves serious attention. I’m not sure it would do women philosophers any favors if everyone knew that women authors were published to satisfy a bias-laden conception of fairness. And once you abandon blind review, you just have to hope that the “good” bias remains fashionable, since nothing in principle prevents the biases of the gate keepers from turning against you.

(1) How does one know when papers are “published [exclusively] on their merits,” without assuming that the philosophy publishing process so closely tracks merit? I thought it was widely understood that what gets published, or not, in quality journals involves various “arbitrary” factors — e.g., the quality and mood of particular reviewers, the editors’ desire to publish on certain topics or not to publish anytime soon again on certain topics, a journal’s virtual refusal to publish on certain topics, etc.

(2) Why can’t we read published papers (that interest us) for ourselves and make up our own minds about their merits? One usually doesn’t have to read very far into a paper to make a personal judgment about whether reading on is worthwhile. Moreover, it seems odd that increasingly heightened concern about pedigree and network biases would leave untouched the kind of publication venue bias according to which being published in high places through some blind process is supposed to be a nearly indefeasible sign of merit.

(3) It seems reasonable to believe that women in philosophy would be done more “favors” by having more of their quality papers published in quality journals — unless there’s reason to believe that good “bias” is unlikely to turn up even a roughly 10 percent increase in quality papers by women. I thought it was widely understood that quality journals generally turn down more quality papers than there is space to publish.

(5) White men in philosophy generally haven’t seemed to suffer too much over the years from hiring and publishing biases in their favor. Indeed, quite a few of these men seem so comfortable that, for example, they’ll wear sneakers, jeans, and a t-shirt or sweatshirt when invited to give department talks. I guess women could live in dread that good “bias” in their favor might cause some white men to look askance at the actual work, leading women in philosophy to prefer a gradualist, status quo approach to maybe being significantly less underrepresented. But this seems like a sucker’s bet.

(6) I thought that the “biases of the gate keepers” have already often turned against women or at least some of the topics they might be more inclined than men to write about — which is why the journal Hypatia, for example, was brought into existence. (Cf. the journal Critical Philosophy of Race.)

(7) “Why must the philosophy profession at this historical moment suddenly prioritize a certain conception of bias-free fairness?” was not a rhetorical question.

(1) if arbitrary factors e.g. mood are influencing decisions, the proper response is not to therefore allow other arbitrary factors. It is to try and minimise them.

(2) This would do away with the entire purpose of having peer reviewed journals and journal rankings in the first place

I don’t really understand the first three recommendations. Does citing women more result in more publications by women?

Also, the “Bechdel Test” seems problematic. Suppose I am writing a ground-breaking paper on William of Champeaux. Maybe there isn’t any secondary literature on that topic at all, much less secondary literature by women. Even if there were relevant work by women, their work wouldn’t count, since it would be cited because it discusses a man philosopher, William.

The point of the Bechdel test isn’t that every movie should have 2+ female characters who have a substantive conversation with each other about something other than a man one of them is wooing. It’s to get us to reflect on the fact that women are sidelined in cinema, and largely relegated to love-interest-related roles. Lots of fantastic movies don’t pass the Bechdel test because (for example) they don’t have many (named) characters (e.g. Moon), and plenty pass that don’t exactly break new ground for women in cinema (e.g. Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Anchorman, No Country for Old Men, Jurassic World, etc.), or pass on technicalities. And a ton fail despite featuring female leads (e.g. The Blind Side, the Twilight saga, Sicario).

Similarly, the point of a philosophy-Bechdel isn’t (or wouldn’t be) that every single article should comply with it. The point (I take it) would be to get us to reflect constructively on our citation and dialogical patterns. So your Champeaux paper might not pass, and that’s OK–there may well be good reasons why it doesn’t pass, like the absence of any secondary literature. But if your paper on convention doesn’t pass, then that’s a pretty good (but defeasible!) indication that something went awry in your research process.

That’s helpful. Thanks.

In case you are interested, I just published a quick and dirty analysis of that paper on my blog, focusing on the finding that women do better in journals that don’t practice anonymous review.

Phillippe, you seem to assume that the following scenarios can’t both be true: (1) an invitation-only journal like PAS without anonymous review (or any external review process at all – see Jenny Saul’s comment below) deliberately invites and publishes papers by women philosophers at a rate proportionate to their representation in the discipline, because they have reflected on the matter and think it’s a good policy to adopt; and (2) Philosophy journals without a deliberate policy of encouraging more submissions from women, and whose editors and reviewers are often uninterested in the kinds of philosophical questions and problems that many women philosophers (and philosophers of color, for that matter) engage, but which have double and triple blind anonymous review processes (with various loopholes), have unconsciously biased review practices that reduce the proportion of women’s papers accepted for publication. Why can’t these two scenarios co-exist, exactly? They seem perfectly compatible to me.

To be clear, nothing I say in my blog post implies that something like 1 and 2 couldn’t both be true, which they could. If you read it carefully, you will see that I only talk about overrepresentation/underrepresentation and not about bias, because as I note at the beginning, the data analyzed in that paper don’t really allow us to draw any conclusions about bias. Women could be underrepresented and nevertheless benefit from a bias in their favor, just as they could be overrepresented and nevertheless be discriminated against. I only talk about bias when I criticize the passage in which the authors speculate that anonymous review might be insidiously biased against women, without even acknowledging that, insofar as the data they analyze bear on bias (which again they don’t really), the hypothesis they propose is at least prima facie at odds with their own data.

Is evolution good and bad and indifferent to human population…Are we free enough to see ourselves as objects of evolution for intension and comprehension…

Perhaps this is addressed in the full article, but it seems odd to assume that the phenomena reported must indicate a bias _against_ women. When I read the part about the discrepancy at the beginning, I was nodding my head, thinking that it made perfect sense, given two _pro-women_ phenomena in the discipline that are already well-known:

1) As I recall from Caroline Dicey-Jenning’s survey a few years ago (I hope someone will correct me if I’m wrong), women getting hired on to tenure-track positions tended to have fewer publications than their male counterparts (which would not be surprising, given a general desire to hire more women); and

2) There is also considerable pressure (both internal and external) in favor of publishing more work by women, when suitable submissions are available. In fact, one often hears complaints that too few articles by women are being published on this or that area, and that something ought to be done about it. I have also seen many people on this blog and elsewhere express a preference for publications by women.

If I’m right about these two pressures existing, and I don’t think that is controversial or speculative (but stand to be corrected), then one would expect the following: the number of submissions and publications by women in the profession will generally be considerably lower than those of men, because (according to the Caroline Dicey-Jennings data, as I remember them), women who publish fewer articles than their male counterparts are nonetheless able to secure equal positions; and yet, when reviewers have a chance to know whether an article is by a man or a woman, they will exhibit a preference for those written by women.

Since this seems to be an efficient hypothesis that saves all the phenomena without introducing any speculative factors to do so, shouldn’t it be preferred? Why assume that, beyond the simple explanation, there is also some faculty people have for inferring the sex of a writer from the style of an article and then selecting against women when the submissions are anonymous, but much less so when submissions are not anonymous?

These results would only support the inverse claim that reviewers have a bias _against_ submissions by women if, say, it were also found that women’s submissions were rejected more often than men’s. But as far as I can see, this is not part of the data set.

This is a very important paper. Here is another explanation of the relatively low proportion of women publishing:

For many years now a significant proportion of the profession has engaged in intentional bias towards women. I assume we all know people who do this, and they often display themselves in the comments section of this blog. They range from those who believe it is the right thing to do, to those who do it because administrations tell them to do it, to those who do it out of fear of criticism if they do not have the mandated proportion of women speakers, staff, students etc. (Statistically, given the higher proportion of men in the profession, especially at a higher level, one would expect speakers and departments to sometime be all or mainly male). As a result of this is a higher percentage of women are given university places, scholarships, conference presentations, jobs etc. than would be the case were philosophical talent alone to be the criterion.

The one place in the profession where this bias in favour of women is not carried out, because it is not possible, is in double and triple anonymous reviewing. Here a smaller proportion of papers are by women than the proportion of women in the profession. This simply reflects the fact that a proportion of the woman being admitted into the profession are not being admitted on the basis of talent. They are being admitted because of sex discrimination.

The solution is not to corrupt the anonymous review procedure in order to increase the number of papers published by women, but rather to end the sex discrimination which results in women being given studentships, jobs etc other than on the basis of talent. There is no ethical justification for sex discrimination – whether for or against women. And by passing over more talented men who then leave the profession, who knows what great philosophy is lost?

Perhaps I should also spell out a point that someone made earlier. If there is no difference in the quality of papers submitted by men and women to anonymous and non-anonymous review journals, then that anonymous review journals publish a smaller proportion of papers by women than non anonymous review journals suggests that the non-anonymous review journals are implicitly or explicitly biased towards women. This undermines the claim that women are the victims of bias and supports the claim that men are the victims of bias.

DanD: Why would the best ‘solution’ be to return to a professional context in which no thought whatsoever is given to historically exclusionary practices and unchecked implicit bias around hiring, conference planning, publishing, recognizing scholarship, etc.? Do you really think that philosophy is better when it gate-keeps on behalf of white men? And do you really think (this strikes me as incredible) that journal editors’ and reviewers’ perception of philosophical talent, and of what constitutes an interesting philosophical question, etc., is wholly neutral and impartial? Wow – that is truly astounding. Maybe take a look at some recent links posted by readers on Daily Nous, such as this one from a black South African philosopher: https://mg.co.za/article/2017-02-23-00-isnt-identity-informed-by-experience

Also look back at Kyle Whyte’s guest blog on DN a while back, about the systematic bias faced by indigenous philosophers trying to publish work dealing with indigenous themes and issues: http://dailynous.com/2017/05/07/systematic-discrimination-peer-review-reflections/

Are you seriously prepared to double-down on your claim that women and philosophers of color are subpar – that they would naturally be less well represented in “university places, scholarships, conference presentations, jobs, etc.” if “philosophical talent alone….[were] to be the criterion”?

JL: As I understood DanD’s comment, he was not claiming some of what you attributed to him, especially that “women and philosophers of color are subpar”. For example, suppose it were the case that women chose to go into philosophy at a far lower rate than men, but that their numbers were increased by the practices DanD calls “sex discrimination”. Then it would be reasonable to expect that among practicing philosophers, women would on average fare worse than men in publishing in anonymously refereed journals, which we assume to be an unbiased measure of talent. I am not endorsing these assumptions, I am just pointing out that this would not involve claiming that women are inherently worse at philosophy than men (if that’s what you meant).

And the charge of “gate-keeping” is perhaps unfair. I don’t think that anything DanD said is inconsistent with making great efforts to encourage members of underrepresented groups to go into philosophy, making the professional atmosphere more, ahem, welcoming, seeking to consider work in all or even especially in underrepresented areas of philosophy. And also I do not think the point would be that “no thought is given to historically exclusionary practices and implicit bias around hiring”. One can attend to those matters by seeking not to be exclusionary or biased. People might disagree about what this amounts to.

From my quick read, DanD’s “interpretation” seems like the obvious one, i.e. the most natural one (not that it is obviously correct), though the data set seems to be quite small — see J Saul’s comment below. That said, even if this is the correct interpretation of the data, that is not to say that his “solution” is correct.

“For example, suppose it were the case that women chose to go into philosophy at a far lower rate than men, but that their numbers were increased by the practices DanD calls “sex discrimination”. Then it would be reasonable to expect that among practicing philosophers, women would on average fare worse than men in publishing in anonymously refereed journals, which we assume to be an unbiased measure of talent.”

There are some pretty complicated counterfactuals involved here, and forgive me if my reconstruction is a misreading, but it seems to me that you’re arguing something like this:

(1) There are more women in philosophy than there would be if people did not make special efforts to encourage women to go into philosophy (what DanD refers to as “intentional bias toward women”).

(2) Thus the pool of women in philosophy (call this set W) includes some women who would not be in philosophy if not for those special efforts, whatever they may be (call this set W1) as well as women who would be in philosophy even if not for those efforts (call this set W2).

(3) Thus it is “reasonable to expect” that practicing women philosophers would have less talent (whatever that means) than practicing men philosophers, because the pool of women philosophers includes both women who would be in philosophy without those special efforts (W1) and those who wouldn’t (W2), while the pool of men philosophers includes only men who are in philosophy without special efforts to encourage them, qua men (call this set M). And this supposed disparity in talent explains different publication rates.

But the move from (2) to (3) only makes sense if we assume that the level of “talent” in pool W1 is lower than the level of “talent” in M. The underlying idea seems to be that the level of “talent” in W2 should be expected to be the same as in M, and the level of “talent” in W1 should be expected to be lower? But it seems particularly dubious that the level of “talent” in M should be expected to be the same as the level of “talent” in W2. If women would choose to go into philosophy at a far lower rate absent efforts to bring them in, the most obvious conclusion is that the women who would choose to go into philosophy are far more motivated and interested in philosophy than average. Because those are the women who ex hypothesi would have overcome whatever factors would be leading women not to choose to go into philosophy otherwise. (Like, a disciplinary culture that’s hostile to women.) If motivation and interest correlates to “talent,” then the reasonable expectation is that W2 is more “talented” on average than M; and if motivation and interest don’t correlate to “talent,” then there’s no reason to expect that W1 will be less “talented” on average than W2. The only reason to think that M = W2 > W1 is if we presuppose that the explanation for why fewer women choose to go into philosophy is that women are overall less “talented” at philosophy; but that’s what you said we didn’t need to claim to make this argument go through.

(For an analogy–the Cleveland and Cincinnati metro areas have roughly the same size. Let’s say that there’s a Phish concert and many more people at the concert are from Cleveland than from Cincinnati. If that’s all we know, and we don’t have any reason to think that people from Cleveland are bigger Phish fans or are more able to afford the ticket, then a pretty likely explanation is that it’s easier for them to get to the concert–for instance, the concert is in Cleveland. Which would mean that the people from Cincinnati at the concert are more likely to be super Phish fans, because they had to overcome whatever obstacles there were for Cincinnatians to get to the concert, like driving the extra three and a half hours.)

This is all taking place at a very high abstract level that doesn’t really have any contact with the realities of gender in philosophy, but since the original argument was a very abstract posit for one explanation of the disparity in publication rates, it might be worth noting that the explanation doesn’t hold up at its own abstract level. But this mini-discussion presupposes a notion of “talent” that I don’t think is well defined or at all helpful; in fact there seems to be some evidence that the degree to which the practitioners of a field are obsessed with “talent” correlates with the extent to which women are underrepresented in the field. (This study from Andrei Cimpian and Sarah-Jane Leslie et al., which Justin covered, and this followup from Bian, Leslie, and Ciprian, which I haven’t seen as much about–that is, I just found it when I was searching for the other paper, but maybe people were talking about it and I wasn’t paying attention.)

I had a version of Andy/DanD’s suggestion raised by a (female) colleague the other day. Here’s the way she ran it. For the purposes of illustration I will speak in terms of ‘aptitude’, leaving open just what that means. Suppose (for the moment–I’ll return to this in a minute) the graduating pool of philosophers are proportionally equivalent in terms of aptitude vis a vis men and women–that is, in a pool with 70 men and 30 women, let’s suppose 10% of each are in the top tier, 10% in the next, etc. In such a situation, if there are exogenous factors that favor women getting jobs (i.e. affirmative action, a social/political climate regarding gender of the sort one sees in some places, etc.), then we would expect that there would be more employed women (proportionally) who showed less aptitude than men. For instance, if there were 20 jobs distributed over that pool of 100 graduates, half of which went to women (but which were otherwise distributed according to aptitude), then we would expect that all 7 of the top-tier men get jobs, as well as three from the next tier. By contrast, with this distribution, almost half of the 10 women who get jobs from this pool (4/10) will be outside the top two tiers of aptitude. This picture of things would explain what we see in terms of publication rates.

Of course this explanation relies on all sorts of presuppositions, the most glaring of which is that the graduating pool contains equivalent distributions of aptitude between the genders. And maybe you’re right that we would expect (proportionally) more high-aptitude women to be represented in the graduating pool. But I don’t see that Andy/DanD’s explanation doesn’t hold up. It just depends on a different batch of presuppositions.

And it’s worth pointing out that the Leslie, et al. study suffers a serious drawback: quantitative GRE score is a far better predictor of gender distribution across academic disciplines than ‘perceptions of brilliance’. Scott Alexander discusses that fact here:

http://slatestarcodex.com/2015/01/24/perceptions-of-required-ability-act-as-a-proxy-for-actual-required-ability-in-explaining-the-gender-gap/

Here’s the takeaway:

“There is a correlation of r = -0.82 (p = 0.0003) between average GRE Quantitative score and percent women in a discipline. This is among the strongest correlations I have ever seen in social science data. It is much larger than Leslie et al’s correlation with perceived innate ability3.

“Despite its surprising size this is not a fluke. It’s very similar to what other people have found when attempting the same project. There’s a paper from 2002, Templer and Tomeo, that tries the same thing and finds r = 0.76, p < 0.001. Randal Olson tried a very similar project on his blog a while back and got r = 0.86. My finding is right in the middle.

"A friendly statistician went beyond my pay grade and did a sequential ANOVA on these results4 and Leslie et al’s perceived-innate-ability results. They found that they could reject the hypothesis that the effect of actual innate ability was entirely mediated by perceived innate ability (p = 0.002), but could not reject the hypothesis that the effect of perceived-innate-ability was entirely mediated by actual-innate ability (p = 0.36).

"In other words, we find no evidence for a continuing effect of people’s perceptions of innate ability after we adjust for what those perceptions say about actual innate ability, in much the same way we would expect to see no evidence for a continuing effect of people’s perceptions of smoking on lung cancer after we adjust for what those perceptions say about actual smoking."

Isn’t it possible that the special efforts/bias towards getting women into philosophy jobs is not giving them an advantage over their equally good male counterparts, but simply compensating for the disadvantages they will have on the job market by virtue of implicit bias and other assumptions about them as women? In other words, these efforts are not making it easier for women to get jobs compared to men, but equally likely (instead of less likely as it would be in the absence of thse efforts).

“Isn’t it possible that the special efforts/bias towards getting women into philosophy jobs is not giving them an advantage over their equally good male counterparts, but simply compensating for the disadvantages they will have on the job market by virtue of implicit bias and other assumptions about them as women?”

Sure, it’s possible. But the implicit bias literature has been part of the crisis of the social sciences that has emerged over the last few years, and all of the quantitative evidence I’ve seen points in the other direction anyway. First, the evidence shows that women tend not be interested in philosophy from the start—the ratio of women to men in philosophy stays roughly the same from the time they declare an undergraduate major until receiving a PhD.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2012.01306.x/abstract

According to an article from Inside Higher Education

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/06/28/georgia-state-tries-new-approach-attract-more-female-students-philosophy

“Through a large-scale climate survey, Nahmias and his students found marked differences in experiences among 700 male and female Introduction to Philosophy students. Women generally found the course less enjoyable, and the material less interesting and relevant to their lives, than their male counterparts. They also felt they had less in common with philosophy majors or instructors and felt less able and likely to succeed in philosophy.”

You might think the last sentence tells us something about the need to teach more women philosophers. But according to follow-up work by Morgan Thompson and her colleagues discussed here:

http://dailynous.com/2016/03/31/why-do-undergraduate-women-stop-studying-philosophy/

“We decided to intervene on the percent of women authors on introductory syllabi for the fall 2013 courses…. However, we did not find that students or women specifically were more willing to continue in philosophy in relation to higher proportions of women on the syllabus.”

Despite an apparent lack of interest in philosophy that begins at an early stage of education, the market seems to be favoring women in hiring (proportional to their representation in the graduating pool) along a number of metrics. When Carolyn Dicey Jennings began her study, someone looked at the publication rates of women and men from different schools in TT hires over the 2012/13 year.

http://genderandprestige.blogspot.com/

What they found was that there was a bias in favor of hiring women even though women tended to publish less, and even for women from low-prestige schools. Unfortunately, Jennings’ subsequent studies appear not to have recorded the data needed to see whether this is a trend. But in a discussion at the APA blog last year, Jennings’ team found the following:

http://blog.apaonline.org/2016/05/03/academic-placement-data-and-analysis-an-update-with-a-focus-on-gender/

“Although more men than women were placed in permanent academic positions within two years of graduation, it is estimated that women have a 0.50 unit increase in the expected log odds of finding such placement. Many prefer to view this in terms of odds ratios. In terms of odd ratios, our findings (in Table 4 here) show the following:

“The odds of women obtaining a permanent academic placement within two years is 65% greater than men when all else is held constant.”

Now this data is at an early stage of collection and analysis, and we will no doubt learn more as we proceed. But given that all of the quantitative evidence (at least that I’m aware of) currently shows that women are at an advantage in the philosophy job market, while the qualitative evidence suggests they are not interested in the discipline from the outset of their undergraduate education and the numbers remain more-or-less constant afterward, the hypothesis that these factors are “compensating for disadvantages” doesn’t seem to be supported.

Does that all make sense?

As Preston noted, this is clearly false. If we assume that talent is similarly distributed among men and women who are interested in pursuing a career in philosophy, then as long as long as the measures in place to increase the proportion of women in the field don’t increase the number of women who are interested in pursuing a career in philosophy but just give some kind of advantage in hiring/admission to those who already are interested, M = W2 > W1 even though we have assumed that talent is similarly distributed among men and women who are interested in pursuing a career in philosophy. Now, it’s true that, if talent is correlated with interest and, if women tend not to be interested in pursuing a career in philosophy, it’s because they face special obstacles in the field, then M < W2 and it may not be the case that M > W1, although this depends on how strong the correlation between interest and talent is, as well as on the level of interest for philosophy in M and W1. But it’s hardly obvious that, if women tend not to be interested in pursuing a career in philosophy, it’s because they face special obstacles in the field. It could just be that women have different preferences than men, so that just as women tend to be more interested in psychology than men, men tend to be more interested in philosophy than women. Of course, those aren’t mutually exclusive hypotheses, it could be that both are true to some extent, in which case whether M = W2 > W1 will depend on exactly to what extent each is true. Another reason why it may not be the case that M = W2 > W1 is that perhaps the measures in place to increase the proportion of women in philosophy act by increasing the interest for philosophy among women, or at least could be designed so as to act in that way, but this is also not obvious at all.

“If we assume that talent is similarly distributed among men and women who are interested in pursuing a career in philosophy”

To be clear, that’s not what I was talking about when I discussed the hypothesis that “women are overall less ‘talented’ at philosophy”; that was meant to compare women as a whole to men as a whole. The ones who are interested in pursuing a career in philosophy are selected from the overall pool.

“it’s hardly obvious that, if women tend not to be interested in pursuing a career in philosophy, it’s because they face special obstacles in the field. It could just be that women have different preferences than men, so that just as women tend to be more interested in psychology than men, men tend to be more interested in philosophy than women.”

Perhaps we should do some empirical investigation to determine which of these is the case. For instance, are women in philosophy subject to pervasive belittling or sexual harassment that might discourage them from continuing on in the field?

Anyway, I think we are at the point where there are (at the very least) enough competing hypotheses on the table that even Andy’s simple assumptions don’t give us reason to think there’s no bias here. We would need to look at exactly why it is that fewer women go into philosophy, and that requires descending from the level of airy abstraction, which is what I’ve been arguing for.

(Scott Alexander’s argument only seems to apply to philosophy if “innate ability” in philosophy is both a real thing and correlated with the quantitative GRE score, which, er, requires further argument.)

“Perhaps we should do some empirical investigation to determine which of these is the case. For instance, are women in philosophy subject to pervasive belittling or sexual harassment that might discourage them from continuing on in the field?”

That empirical investigation has already been done, Matt, and the matter is clear. In colleges and universities that don’t require all students to take a freshman philosophy course, there is no difference in the percentages of women in freshman or sophomore courses, junior or senior courses, taking majors, or taking advanced degrees in philosophy. Whatever factor leads proportionally fewer women to be interested in taking philosophy shows up in or (more commonly) prior to a woman’s coming to university for the first time. Therefore, the hypothesis that pervasive belittling or sexual harassment is a major cause of the relatively low representation of women is not plausible, given the facts.

“Anyway, I think we are at the point where there are (at the very least) enough competing hypotheses on the table that even Andy’s simple assumptions don’t give us reason to think there’s no bias here. We would need to look at exactly why it is that fewer women go into philosophy, and that requires descending from the level of airy abstraction, which is what I’ve been arguing for.”

To be clear, I at least was not thinking in terms of whether “Andy’s simple assumptions don’t give us reason to think there’s no bias here.” The issue, for me, is whether the only reason to think a divergence in aptitude relative to gender representation in philosophy is due, as you say, to “women as a whole” being “overall less “talented” at philosophy” than men. I’ve given you a concrete case where that is not the only reason, and Justin Kalef spells out another example in response to Hayze below. But I agree that we need more data. That’s partly why the Phil Studies paper is so galling—it just doesn’t give us enough relevant information to see what’s going on. Hopefully Nicole’s updates will help!

As for Scott Alexander’s argument against Leslie, et al., the point is not whether Alexander’s explanation applies to philosophy. The point is the Leslie, et al. methodology suffers from a serious drawback and should not be relied on in drawing conclusions about the relationship between apparent and veridical perception of innate ability.

Helen, which empirical investigation are you referring to?

It doesn’t really matter, the claim you made before, namely that « the only reason to think that M = W2 > W1 is if we presuppose that the explanation for why fewer women choose to go into philosophy is that women are overall less “talented” at philosophy », can still be shown to be false by essentially the same argument. Indeed, if men are typically more interested in philosophy than women, then it’s possible for M = W2 > W1 to be true even if talent is similarly distributed among men as a whole and women as a whole. For this to be the case, we just need to further assume that men who are interested in philosophy are no more/less talented than woman who are interested in philosophy (which can be true whether talent is correlated with interest in philosophy or not, it just has to be the case that whatever correlation exists is the same for men as for women), for then talent is similarly distributed among men and women who are interested in philosophy and the same argument as before shows that M = W2 > W1. (Actually, even in that case, it could still be that M > W1 is not true, but you would have to make some really implausible assumptions for that to be the case.) Of course, as I already noted, if women who are interested in philosophy tend to be more talented than men who are interested in philosophy, which could be the case if, for instance, they had persisted in their interest for philosophy despite widespread discrimination against women in the field, then M < W2 and it may not be the case that M > W1, but that’s not even necessarily true since it depends on the exact assumptions we are making. This shows that M = W2 > W1 could be true, even if do not assume that « women are overall less “talented” at philosophy », hence that your claim is false. As I noted in my previous comment, even if men are typically more interested in philosophy than women and talent is similarly distributed among both sexes, M = W2 > W1 could still be false provided that the measures in place to increase the proportion of women in philosophy act by making women interested in philosophy who otherwise wouldn’t have been interested in that field. I suspect you may have implicitly been making that assumption, but 1) that’s probably not how the measures that exist act for the most part and 2) even if it were, M > W1 could still be true depending on the details, so your claim is false even if we make that assumption.

I’m all for empirical investigation, but assertions that « women in philosophy subject to pervasive belittling or sexual harassment that might discourage them from continuing on in the field » are not evidence, no matter how often they are repeated. Similarly, appeals to anecdotal evidence don’t have a lot of weight, especially since there is also a lot of anecdotal evidence on the other side. So far, if we restrict ourselves to non-anecdotal evidence (as indeed we should), we have good evidence that women are favored in hiring. I’m not going to go through this again, since I have already discussed this ad nauseam, but the data were analyzed in various places, such as in the comments of this post. In the course of that conversation, someone asserted that women were less often invited to give talks than men (among many other unsubstantiated claims), so I did a quick test and found that, on the contrary, they were invited far more often than their share of the profession would have you expect. It was a quick and dirty test, but it would be very easy to do that seriously. I bet it would confirm my conclusion, but I don’t see people who make that sort of claims rush to test this hypothesis, even though again it would not be very hard. Of course, all that is compatible with the hypothesis that a lot of women are discouraged from entering/continuing in the field, but it clearly makes it less plausible. But it’s actually worse than that, because even if you could present good, non-anecdotal evidence that « women in philosophy subject to pervasive belittling or sexual harassment that might discourage them from continuing on in the field », it would not be enough to explain the underrepresentation of women in philosophy, a point that seems to be lost on most people. Indeed, this would explain why women who are interested in philosophy are less likely to enter the field relative to men who are similarly interested, but it wouldn’t explain why women are underrepresented in philosophy but not in other fields. So you’d have to also show that, whatever discrimination women face in philosophy, it’s much worse than in other fields such as psychology, which are dominated by women to the same extent that philosophy is dominated by men. In fact, it’s even worse than that, because what you would really have to show is that sexism was less common in those fields several decades ago, when the restrictions against the entry of women in academia were lifted. Indeed, given that women are overrepresented in psychology, it wouldn’t be surprising if there were less discrimination against them in that field compared to philosophy, for purely statistical reasons. Presumably, there was no less sexism in psychology, English, biology, medicine, etc. than in philosophy 50 years ago or so, yet as soon as the restrictions against women in academia were lifted, these fields quickly reached gender parity or even became numerically dominated by women, whereas philosophy remained dominated by men. The hypothesis that men are more likely to be interested in philosophy than women explains that, whereas the hypothesis that women face a lot of discrimination doesn’t. Moreover, as Helen pointed out, the different preferences hypothesis actually has some direct empirical support. (I don’t have time to look for links, but I remember this was discussed on various philosophy blogs. Hopefully Helen remembers where this was.) So you’re right that there are several competing hypotheses, but they’re not equally plausible, not by a long shot.

Thanks, Philippe.

Yes, large-scale empirical research has been done on this now, by people who, if anything, were probably hoping for the opposite conclusion. Those interested can read a summary here: http://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2013/06/17/192523112/name-ten-women-in-philosophy-bet-you-can-t

This was widely discussed not long ago. It establishes a couple of things beyond any serious question. First, women are not showing up in great numbers at university keen on studying philosophy and then turned off by sexism, overt or otherwise. Women are, by and large, choosing other majors and graduate degrees because philosophy was never very interesting to them. Second, women by and large do not find philosophical discussions and classrooms overly combative or hostile.

These figures have shown so many times now that it’s kind of puzzling that anyone still asserts otherwise on the basis of no evidence.

Thanks, Helen. In case you are interested, I wrote another, much longer blog post in which I share my thoughts about the underrepresentation of women in philosophy. I discuss these findings, among many other things.

What are the areas of philosophy in Figure 6? LEMM is obviously Language, Epistemology, Metaphysics, and Mind, and S is presumably science, but I can’t figure out what V, H, and G are. Violence? History? Gender? Vreligion?

V = value; H = history; G = ?

value theory, history of philosophy, generalist journals

There’s a lot of interesting and important data here, but the bit about non-anonymous review helping women comes from just two journals: Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, and Mind and Language. PAS is almost exclusively invited (so not reviewed at all), and the decisions about who to invite include explicit discussions of making sure there are decent numbers of women. Mind and Language is interdisciplinary with two fields– Linguistics and Psychology– where there are lots more women than Philosophy has. So I don’t think this bit can be relied on.

Yes, more data is definitely needed and we now have it (see above), so keep your eyes out for the JSTOR data!

I agree with Jenny Saul, Philippe Lemoine (see his above linked blog post), and Mary Leng, that the evidence presented in the paper is far too scant to conclude with much confidence that non-anonymous review generally “helps” or is “biased toward” women. However, I also agree with Lemoine that ideology is trumping evidence when the authors, apparently taking it as obvious that anything other than publication rates proportional to professional representation must result from invidious bias, go on to speculate wildly about why blind-review might be invidiously biased against women.

I have serious doubts about the genuine anonymity of anonymous review because of the existence of informal networks (the “cool kids”), conference and colloquium presentations, and the posting of paper titles on the internet. Still, it is the best system we have for sussing out the best work in philosophy and our aim, so I hope, is to publish and recognize the best work, independent of the identity of its author.

Thanks Jenny, that’s helpful. So the higher proportion of women in Mind and Language than in journals with anonymised reviewing may well be due to there being a higher proportion of women in Linguistics and Psychology. And the higher proportion in the Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society is due to explicit bias in favour of women.

What’s the argument for equating (1) inviting women with an eye to gender ratios, with (2) explicit bias in favor of women? Is it unreasonable to think that 1 might simply constitute countering other biases, or systemic problems with putatively blind review?

Here are (1) a paper (forthcoming in Hypatia) on the under-representation of women in prestigious ethics journals, and (2) a paper (forthcoming in Public Affairs Quarterly) in which one of the authors of the first paper argues that quotas in publishing are not obviously objectionable:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/gbabd7vlsvptwbw/Krishnamurthy%2C%20Liao%2C%20Deveaux%2C%20Dalecki-UnderrepresentationofWomeninPrestigious%20EthicsJournals.pdf?dl=0

https://www.dropbox.com/s/yxm612kkls78b1n/Krishnamurthy-ProportionalRepresentation.pdf?dl=0

I find it somewhat incredible that the author of the second paper so breezily posits explanations (and extremely speculative ones at that) that rely on implicit bias and stereotype threat, even though it is well known that research on both these purported phenomena has faced much criticism lately.

I told my partner about this, and she had a completely different take that might be worth putting on the table. If women are publishing at a lower rate than men, that might be because women prioritize other activities and choose not to publish at the same rate as men. The assumption that women ought to publish as much as men implies that women’s careers ought to look like men’s careers or else they are less valuable. This assumption devalues the professional priorities and choices that women are actually making.

I know that the topic of gender is surrounded by landmines, so let me emphasize that I am reporting a view that seems worthy of consideration and not endorsing that view.

Thanks for this comment, which might help to explain some of what’s going on. And it highlights a crucial point which has not, to my eye, been discussed here: so there is this thing that men do more than women (submit papers to journals), and when the disparity emerges, people fret about bias and quotas instead of fretting about the fact that this single activity makes up so much of our conception of what an ideal philosopher does. Is it REALLY progress towards equality if this stereotype remains untouched and we somehow encourage more women to submit papers to an average of 8 cranky anonymous reviewers so that they can eventually be read and cited by no-one?

You’re assuming that the differential rate of publication is due to a differential rate of submission, which is consistent with the data but not yet thoroughly investigated. People are expressing worries (perhaps prematurely) because the differential rate of publication may not be due simply to a differential rate of submission.

I suspect that women do often prioritize other activities, but I don’t think this is as innocent as it sounds. For instance, I suspect that if the study controlled for hours spent parenting or in other care-taking roles, we might have an explanation of the discrepancy between hiring and publication rates. (B/c women need the jobs, but once women have the jobs, their pay isn’t, at least not directly, contingent publication under the belt. Of course, people with fewer publications might tend to be paid less, but they presumably nevertheless retain their foothold in their jobs. Which is enough, from a practical perspective.) Thus the disparity might be the result of gender discrimination OUTSIDE of philosophy–as in, in the society at large, when it comes to expectations around time spent on care-taking work. (That’s not to say that editors’ and referees’ preferences for philosophical topics that don’t tend to be covered by women is not a factor.)

It’s alright but all the time it is women who are the emotional laborers. We can’t easily quantify it, but I think we all assume the emotional servicing is left to women and men are given a free pass. This, I think, is an anachronism from the 60s left: perhaps there are men who have no compunctions, no feelings, and they are bound with women who, bereft, serve those men each night with a smorgasbord of empathy. Yet academic philosophy comes across like all the other bourgeois careers: a snake-pit where bright, motivated individuals tweet rapidly to better shove their credentials down one another’s throats.

I graduated in 2011, and I’m amazed to hear there is still sexism in the discipline. What you;re saying about care-taking work is just a reality some people need to accept: there is this notion you can fanny about thinking about metaphysics in your study and worry about nothing else, but that isn’t the world and it never has been; it is good if you now have to start thinking about how those around you. The feminist angle needs to be seen as a plus for the old-guard for it to get traction I think though.

Robert x.

And you drew these conclusions from this conversation how, exactly, Robert?

I am late to this conversation, but what could have been useful information is completely uninformative without knowing the percentage of women who submit work. B (above) might be right, but we have no way of knowing without these stats. And unless I am missing something, the discussion about the non-anonymized journals seems misleading. It might be that women are simply submitting more work to such journals, and the percentage of accepted work reflects only that.

Given that there are only two journals in the data set that practice non-anonymous review, and given that these two journals differ in a variety of ways from typical philosophy journals and from each other (one is heavily interdisciplinary; the other publishes mainly commissioned articles), there is absolutely nothing one can conclude about women and anonymous review in philosophy from this data. Absolutely. Nothing. Please stop the speculation: it is silly.

It’s worth noting that the authors themselves note something like this, in a paragraph which begins: “One alternative explanation for why journals practicing non-anonymous review tend to publish more women than journals which do not is that there is something special about the two non-anonymous journals we examined.”

I’m not agreeing with their alternative explanation. I’m pointing out that there is nothing to explain.

The non-anonymous journals in the authors’ data set publish more women than the anonymous journals in their data set. You say there is nothing to explain, because there are only two non-anonymous journals, and given that they are unique in certain ways. The authors say the fact that the non-anonymous journals in their data set publish more women can be explained by the fact that there are only two such journals, and they have idiosyncratic practices. This seems like a merely semantic difference between you and the authors.

I really feel that these results should not even have been posted, and I rarely feel that way about a DN post.

As others have said, without submission rates, these data are meaningless. Or they would be meaningless, if they weren’t inviting wild speculation, and inspiring people to propose solutions in advance of knowing whether and where there is a problem. Since these data are having these consequences, they’re worse than meaningless: they’re actively misleading.

If the reason for the disparities is that women simply submit less, then several of the proposed solutions to the problem (if it’s even a problem to begin with) are likely to be onerous *especially* to women. Women often do still have more non-research responsibilities, and therefore less time to write. It’s also possible that women are more likely to self-censor out of fear of not being sufficiently knowledgeable. These things may be problems, they may even be social problems, but they are not problems that it is easy or perhaps even appropriate for journals to deal with. Proposed solutions such as encouraging authors to read “all the current literature relevant to one’s area of research” raises the bar higher for everyone. And if that’s where the bar belongs, fine, then so be it. It makes no sense to do it for greater equality in gender representation however, if women are already less likely to believe that they can clear the bar where it is now…

Neil, Jenny Saul states that gender is a factor taken into account by the Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society when deciding whether to invite someone to submit. That is explicit bias.

Ash, knowing submission rates of women to journals with anonymised reviewing would only tell us how many papers were submitted by women which were not of sufficiently high standard to be published. What would you infer from there being a relatively large number of these or a relatively small number? That compared to men, women tend to churn out quantity rather than quality or tend to not produce much, respectively?

The interesting point is how few papers by women were of sufficiently high standard to be published in good journals with anonymised reviewing.

DanD, your remarks are irrelevant to the point I made: that it is impossible to draw any conclusions about gender and anonymous review from this data set. To make such comparisons, you need a much broader set of data, concerning representative journals with and without anonymous review. I don’t think journals that are broadly comparable to those with anonymous review but which lack actually exist in philosophy, but if they do they’re not included in this data set.

“knowing submission rates of women to journals with anonymised reviewing would only tell us how many papers were submitted by women which were not of sufficiently high standard to be published.”

That’s one potential explanation for women submitting a disproportionate number of papers that don’t get published. Another possibility would be bias, perhaps implicit, despite nominally anonymous review.

Suppose there were no discrimination or gender bias or anything like that going on. How would the numbers then look? Would the percentage of papers by women equal the percentage of women faculty? I don’t know, but that seems like a substantive assumption to make.

Good question, Hayze. Here’s how I see it: if there’s anything wrong with my thinking, I hope someone will point it out.

Let’s imagine a world in which a) there are exactly 100 people graduating with PhDs in philosophy every year; b) there are exactly 30 tenure-track positions available every year; c) exactly one out of every four people initially interested in philosophy is a woman (for reasons no more interesting than the reason why far more women than men seem attracted to studying sociology or English literature); d) people continue on in philosophy in exactly the proportions to which they’re initially attracted to it; e) the initial talent and degree of hard work exhibited by men and women in philosophy is exactly the same, on average; f) there is absolutely zero discrimination or gender bias in publication decisions, and all such decisions are perfectly blinded anyway; and g) the pressure to publish once one secures a tenure-track position is in keeping with one’s prior rate of publication.

In this world, there would naturally be an imbalance in male/female hires if there were no intervention. Let’s imagine that a number of search committees in this world desire to adjust the balance to make representation of men and women in the discipline more equal. All in all, the search committees will hire an equal number of men and women each year. And the men they hire will be the best men available, and the women they hire will be the best women available. Let’s also assume that ‘best’ is largely defined by the number of publications in top journals the candidate has for each year. Let’s say that the 100 new PhDs, ranked from 1-100 on the basis of annual top-journal publications, publish as follows: #1 publishes 10 articles, #2 publishes 8, #3 publishes 7, #4 publishes 6, #3-#10 publish 5, #11-#20 publish 4, #21-#30 publish 3, #31-#50 publish 2, #51-#70 publish 1, and #71-#100 publish 0. Moreover, since the women are no more or less talented or hard-working than the men, they are distributed evenly through the 100 as follows: positions 2, 6, 10,14,16… etc.

So, in this toy example, in which there is no gender bias at all (aside from a desire to hire as many women as men) and no difference in talent or work levels between men and women, what would we expect?

The top 15 men would get tenure-track jobs. These men would be in positions 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20. So, their total publications in a given year would be (10 + 7 + 6 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 +4 +4 +4 +4 +4 +4 +4 +4 =) 75 publications.

The top 15 women would also get tenure-track jobs. These women would be in positions 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, 30, 34, 38, 42, 46, 50, 54, 58. So, their total publications in a given year would be (8 + 5 + 5 + 4 + 4 + 3 + 3 + 3 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 1 + 1) = 47 publications.

The exact numbers here are irrelevant: one could adjust the constraints to make the difference between male and female publications as great or small as one likes. My point in presenting this toy example is to show that, given nothing more than a much higher percentage of men than women being drawn to philosophy in the first place, paired with a strong tendency among search committees to hire men and women equally, one would expect there to be such a difference in the _absence_ of any editorial or reviewer bias for or against articles written by women.

Looking at the data collected by the APA, that seems not to be true. A couple of journals published a higher proportion of women-authored papers than were submitted, but others published a proportionate rate (JAP, CJP) and still others (e.g.., JPP) published a at a lower rate (35% submissions by women, but women authored papers represented only 30% of papers published for the period given). And of course, the majority provided no demographic info so we really don’t know the broader picture.

Thanks for your comment, JL.

I don’t see why the results you mention provide evidence that anything is going on other than the innocuous things taking place in my toy example — in other words, just what one would expect, given the proportions of men and women doing philosophy at all levels and an active desire on the part of search committees to hire women at least as often as men (actually, even a tendency to hire one woman for every two men would be sufficient, in my toy example, to explain the discrepancy).

To show that there’s something left to be explained here, you’d have to provide good evidence that, say, women’s overall submission/acceptance ratio is higher than men’s. But as you say yourself, what we find are some journals in which women’s rates of submissions over acceptance are higher than men’s, some in which it’s lower than men’s, and some in which it’s equal. I don’t have access to the full article, but perhaps there aren’t enough articles in any of these journals in particular to make those rates statistically significant over the given period.

Moreover, there are other plausible factors, other than sexually discriminatory assessment, that one could add to the toy example that might make sense of a discrepancy in the submission/acceptance rate for women between journals, if that discrepancy is statistically significant (again, I don’t know if it is). My toy example assumes that women and men are equally likely to work in all fields of philosophy. However, that is unlikely to be true. There seem to be far more women than men working in feminist philosophy, for instance; which means that — if f is the percentage of philosophers who are female — one would expect not only that the subset of philosophers working in feminist philosophy is greater than f, but that (of necessity) the subset of philosophers not working in feminist philosophy is less than f. It’s often also said that feminist philosophy has its own distinctive practices and values — practices and values that might not always square with the philosophical direction of certain journals. If we add into the mix that some of those who primarily do feminist philosophy will sometimes submit their work to (perhaps more prestigious) journals that operate with different values, then one would therefore expect to see different submission/acceptance rates for women philosophers across journals even if the editorial process is properly blinded and there is no bias for or against women in anyone’s acceptance or rejection of submitted articles. And the recent _Hypatia_ scandal has clearly shown that at least a sizable contingent of people working on feminist philosophy do so with a set of values that does not mesh well with the values of objectivity, free inquiry, etc. pursued by most other areas of philosophy.

I’m not trying to say that this is the explanation of the discrepancy between journals (again, assuming the discrepancy is statistically significant). I really don’t know if it is, and it’s the sort of matter that could (and should) be settled empirically. But it is the sort of plausible alternative explanation that would have to be ruled out in order to come to the conclusions that the authors of the article seem to have reached.

A quick glance at the APA surveys shows that women generally submit at a rate much lower than their acceptance rate:

http://www.apaonline.org/page/journalsurveys

Most (75-80%) journals that provide this data have women accepted at a rate more than or equal to their rate of submission–some over twice as much. I hope this puts to rest the idea that blind review is bad for women. It in fact, appears to be quite *good* for women, since they are publishing at much higher rates than they are submitting.

I’m annoyed the authors included non-anonymous journals in here. This would only be useful information if there were a statistically significant number of these journals (there are not), and if they utilized basically the same processes as anonymous journals, sans anonymity, which clearly, they do not.

Why, then, are women underrepresented? I can think of lots of reasons, having mostly to do with departmental and domestic demands on time. I do NOT think it has much to do with bias in the review process, since, as indicated by the above figures, anonymous review generally benefits women authors.

Very few journals here report submission rates, so we are collecting more.data and hope to analyze it with the JSTOR data we now have from a much wider sample of journals. Still, we thought the hand collected data from highly ranked journals was worth putting out there!

Philosophers’ partial engagement with the empirical literature sometimes distorts these conversations with a case in point being the authors’ reliance on a highly questionable study to inform their perspective on blind review: Budden et al. (2008).

Though initially feted as “one bright light,” Nature quickly walked back its endorsement writing that Budden et al. failed to provide “compelling evidence” and “we no longer stand by the statement…that double-blind peer review reduces bias against authors with female first names.” To take Budden et al. (2008) at face value overlooks several other critiques including those by Webb et al; Hammerschmidt et al.; and Whittaker. Also ignored are two other studies Budden et al. ran that failed to turn up evidence of sex differences in acceptance rates. The same goes for studies by Nature: http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v9/n7/full/nn0706-853.html and one by Brooks et al. Budden acknowledged some of the limitations (almost ten years ago) noting that “alternate variables” could explain their data. This should definitely be old news by now.

Budden et al. is not the only evidence of gender bias in peer review (though it is the authors’ sole example of recent or even semi-recent empirical work) and as is often the case in social science, results are somewhat mixed–somewhat. However, if the context above helps set our expectations we are mistaken to find it surprising that women are not underrepresented at the two non-anonymous journals under consideration. That the authors and referees saw fit to put much weight on a piece field experts received so skeptically also illustrates the need for a broader conversation about how philosophers are handling the scientific literature, not least research on gender bias.

Let’s stop cherry-picking, especially when the cherry is rotten!

Thanks for the survey of the literature! I don’t think we put much weight on the paper, it just seemed a relevant citation and I will try to reference the follow on debate in subsequent publications :).