The Ethics of Honoring

The recent wave of student protests in the United States have focused on a range of issues related to the status and treatment of racial minorities and other vulnerable parties on campus. One issue that has come up on several occasions are the ways in which universities have decided to honor various historical figures—for example, by naming buildings after them, or having statues of them.

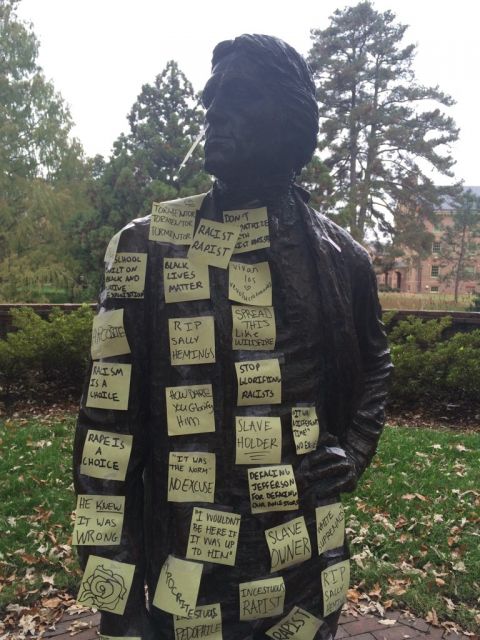

Last week, students at Princeton University were protesting the university’s prominent recognition of Woodrow Wilson. Wilson was president of Princeton prior to becoming president of the United States, and Princeton has a college and a school named after him. Though he was a progressive on many matters, as Inside Higher Ed reported, “historians have also noted that he was an unapologetic racist who took many actions as president of the United States that held back even minimal rights for black people.” Recent protests at Georgetown focused on the fact that one of its buildings was named for a former university president who sold off some of his slaves to a plantation to pay the university’s debt. And now, IHE reports that at the College of William & Mary and the University of Missouri, “critics have been placing yellow sticky notes on Jefferson statues, labeling him—among other things —‘rapist’ and ‘racist.'”

These developments may have some people wondering what the appropriate stance is towards honoring historical figures who have held what are today understood to be highly objectionable views, or acted in highly objectionable ways. To shrug off the concerns and say “no one’s perfect,” seems insufficiently sensitive to the ways in which such honors might contribute to an unwelcoming environment for some students. Yet to require historical figures to be morally unobjectionable by today’s standards in order to be honored seems unduly strict and inflexible. We might recall that even moral heroes are not morally perfect (see, for example, Lawrence Blum’s “Moral Exemplars” essay).

I am not aware of work on the ethics of honoring historical figures. Perhaps this is an area in which philosophical expertise can help clarify an issue of current pressing concern. Thoughts welcome.

(image from IHE)

Why the restriction to “what are now understood to be” objectionable attitudes? Wilson was a horrible racist by the standards of his own time.

Adjusting standards down to the standards of the historical figure’s time does make Jefferson look a bit less bad, though there were still ways in which he was worse than his contemporaries. But it is a real red herring in disputes over Wilson.

Very good point. Thanks, Brian.

If someone had taken part in the Holocaust that would clearly justify barring them from any sort of public display of honor even if they had done some sort of good elsewhere along the way. Similarly, if someone partook in slavery or supported American apartheid then it should bar them from a public display of honor. No one is morally blame-free, but these are levels of injustice of a magnitude that ought to disqualify someone from being put on a pedestal for countless generations to glorify. It minimizes their injustices. Having their statues on display is actually a whitewashing of history since it gives the false perception that their injustices were forgivable. Taking down their statues would properly re-conceptualize American history in the public eye for the true horrors that have occurred since the first settlers arrived.

Who made you the arbiter of the forgivability of sin?

I don’t know – there are a lot of us out there who think taking an active role in perpetuating the Holocaust, slavery, and apartheid are unforgivable injustices. You must be a much more forgiving person than I. Good for you.

What if two hundred years in the future we have collectively decided that some common practice today is actually morally abhorrent, in the same way we have with slavery and other forms of institutional racism? Abortion and factory farming seem like prime potential examples (though I don’t mean to spark a debate on those subjects). Are we then to bar from recognition forevermore all public figures who were pro-choice or carnivores? That would leave us with very few candidates indeed, and it strikes me as unnecessarily harsh toward the past and even hubristic, ignoring what practices of our own might be condemned by future generations.

I think where the disconnect seems to come in is this idea that ceasing to honor an individual means we are erasing them from history. Taking down some public recognition of honor is not equivalent to burning books. If fact, doing so is likely to correct distortions in what we are taught. For example, I was taught absolute lies about Columbus, and we sang odes to him in our elementary school music classes. By ceasing to honor him, we can correctly learn that he did not “discover” America, but was the first European to successfully launch white colonization of this country. We can also learn that he was a genocidal maniac. It’s hard to learn the truth if we are blinded by propaganda aimed at glorifying these villains who happened to win and write their own version of history.

You measure how much net utility would result from each of the possible courses of action and act accordingly. #wevebeensyaingthisforcenturiesidontunderstandhowthisisstillaquestion

Ajume Wingo and I will have a pair of essays that discuss this topic to some degree in an upcoming Journal of Ethics. The question of the proper role of honoring, period, within liberal culture is interesting, since it seems to require a vaguely undemocratic elitism and an obfuscation of unflattering facts about historical figures. I argue that honoring is an important safety valve insofar as a democratic culture can offer lasting honor to great individuals in return for their rejection of material or political supremacy. So a culture that doesn’t honor its great individuals robs them of possibly their most powerful incentive, and unwittingly encourages the great among us to pursue lower aims such as power and wealth. This idea (not uncommon in the enlightenment) has made a big comeback with historians and political theorists in recent decades (Paul Rahe, Gordon Wood, Garry Wills, Sharon Krause, Lorraine and Thomas Pangle, and especially Douglass Adair). If that’s right, we have a prima facie obligation to honor leaders who helped strengthen democratic processes, or even could have (but didn’t) harm them.

Obviously there will be many different theories of whom we ought to honor and how. The fashion now seems to be judge the worthiness of public honor on the basis of the worst thing the figure did (in public or private), not the greatest thing, or even the moral quality of their life or legacy all-told. I think that’s warped, and it wouldn’t leave us many people to honor (don’t forget MLK’s plagiarism problems, or Mandela’s cozy affiliation with dictators, if we’re going to be consistent). I also suspect that the iconoclasm is to some extent propelled by a misguided egalitarianism of honor: we feel better about ourselves when we knock the greats. But there really are some outstanding individuals, and it may be that bringing them down to our level is just as inaccurate in the other direction.

You mention that if we were not to honor many of our historical leaders that consistency would force us to also not honor MLK. You specifically mention MLK’s plagiarism problems. No one is morally perfect, but it seems that MLK’s positive contributions to the world far outweighed whatever blemishes he may have had such as plagiarism problems. Can you say that about someone who enslaved people or committed genocide? I don’t think so. I don’t think honoring someone necessarily requires that they be free from all moral blameworthiness, but surely there is a threshold that once surpassed ought to bar someone from lasting public honor (such as a widely displayed statue for countless people to see). If taking a direct and active role in the institution of slavery, for example, does not pass that threshold, I don’t know what does. If you don’t think upholding slavery ought to disqualify one from public honors it is probably because our country has so longed glorified slave owners, and their “greatness” has been indoctrinated into us at such an early age, that we’ve minimized their perpetuation of this injustice in our minds to avoid cognitive dissonance (“oh… but everyone was slaveholders back then, etc.”).

The presence of a specific victim (or descendants of a victim) would be one obvious bar to use in sorting out which blemishes are significant enough to merit withholding honor.

“The fashion now seems to be judge the worthiness of public honor on the basis of the worst thing the figure did (in public or private), not the greatest thing, or even the moral quality of their life or legacy all-told. I think that’s warped, and it wouldn’t leave us many people to honor (don’t forget MLK’s plagiarism problems, or Mandela’s cozy affiliation with dictators, if we’re going to be consistent). I also suspect that the iconoclasm is to some extent propelled by a misguided egalitarianism of honor: we feel better about ourselves when we knock the greats.”

This is a display of protesting too much and evidently knowing too little. Jefferson, for example, was a slave owner, slave rapist, slavery apologist, and foundational American racist ideologue. He did not merely have a “sexual relationship” with his slave Sally Hemmings: chattel slaves, of course, were not capable of anything like consent to sex with their masters (or mistresses), let alone as children. If you’re tempted by the thought that this merely reflects “our” contemporary standards, you might take the trouble to consult slave narratives to find out about their experience and moral perspective : http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai/enslavement/text6/masterslavesexualabuse.pdf.

Nor, surely, does one have to be African American to recognize that truly honorable people, whatever their great accomplishments, wouldn’t enslave their own (unacknowledged) biological children.

I can assure you that pointing out such brutal, inconvenient facts of American history isn’t simply a matter of “fashion now” or wanting to “feel better about ourselves” — at least for some of us. Let’s charitably assume that condescendingly comparing such facts to plagiarism or seeking assistance from dictators in order to fight Apartheid (since “free” societies refused to help) is supposed to be a reductio.

As for Woodrow Wilson, he was a Klansman theorist and activist and an arch segregationist (http://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2015/11/20/9766896/woodrow-wilson-racist). His views and attitudes about race did not merely fail by contemporary standards: his actions as a political and academic leader were plainly racist by the standards of a significant number of “us” — black and white — at the time.

Anyway, if renaming buildings or removing monuments is generally too much to bear, there’s no reason small, readily visible plaques couldn’t be added that sum up the brutal facts. Rather than “erasing” history or undermining public culture, this additive proposal would only give us a fuller, far more accurate perspective of “outstanding individuals” in American history. Or maybe there’s something deeply problematic that I fail to appreciate about this seemingly modest proposal.

Commentator, Lionel McPherson,

Commentator brings up the fact that de-honoring a previously honored individual doesn’t entail erasing them from history. I agree with that, as well as the proposition that honoring a civic hero with a checkered history likewise doesn’t prevent us from teaching about the evils they did.

We can also decouple honoring an individual from celebrating them as a moral exemplar. It seems appropriate to retire a jersey of a sports star, even if they had bad character off the court. Every honor culture knows this. It’s not like the Greeks thought Achilles was smart or wise or even acted in the interest of the Greeks, or that every philosopher we honor is morally impressive. Do parallel considerations govern civic honor?

I am pretty aware of, although not expert on, the Jefferson case, having recently dug into the question for my research on this question. I absolutely reject any suggestion that my position is one born of callous indifference—especially since I made no comment about any specific case of honoring. In any event, Mandela himself, when he took power, although dismantling some apartheid symbols, allowed many others to exist: there are quite significant monuments celebrating white supremacy in South Africa today, right on the most prominent public grounds. Maybe Mandela was just politically savvy, as he was very committed to making white South Africans feel like they had a future there (“Some of their heroes may be villains to us….and some of our heroes may be villains to them,” he said at one point where he urged restraint at monument removal). Whatever his motives, he wasn’t unaware of the injustice of apartheid. Good people who aren’t ignoramuses can disagree about this.

So can you morally honor someone as an extraordinarily good F (where being F is a good quality) without honoring them as “honorable” full stop, or in some other way? The answer to that is yes. The problem here is that the property in question is roughly “civic excellence,” and that includes all sorts of things in our society. Jefferson scores really low on some measures, really high on others, even within that narrow question. The question may better be *how* to honor him—maybe the plaques are the solution, I don’t know—than *whether* to honor him. His impact on our good political values, even those of freedom, was tremendous. The idea that a morally conscientious 18th-century guy just going about his non-slaveholding business, farming radishes, deserves as much positive regard as Jefferson seems ridiculous to me. So I conclude he must be honored somehow, despite his moral failures.

Why is it not enough simply to educate about Thomas Jefferson in a full manner that both describes his accomplishments and his severe moral failings? It’s not as if Jefferson’s name would somehow be forgotten in history like any ordinary radish farmer from his time. To honor him with a public statue or memorial is to sing his praises loud and wide and is thereby not only a distortion of historical truth, but a tremendous offense to all those he has wronged and their descendants. When children learn the truth in classrooms, that one of the founding fathers of this nation enslaved his own children, then they can decide for themselves whether they want to join in the nationalistic chorus of propaganda and glorification or have a more sober, level-headed evaluation of who this man was.

Commentator I fully support the educational scheme you propose. I also agree that we should have sober, level-headed evaluations of anyone, including founders. However, I think someone like Jefferson should (in some way) be honored, not just “remembered,” for reasons I hinted at earlier.

That said, I think “honoring” connotes different things to us: your view is that we are honoring more holistically than anything I am advising we do (or continue to do). I’m not saying you’re this extreme, but some people interpret honoring as something akin to Baal worship. This is because we don’t think a lot about honor, and our distinctions are crude. But I want to stress that people in functional honor cultures are completely accustomed to honoring people they flat-out loathe. This is no different in principle to resigning yourself to a government you detest (“If Bush/Clinton gets elected I’m leaving!….) It seems amazing to those from totalitarian cultures without good democratic virtues that we don’t revolt when our candidate loses. Likewise, it seems impossible to many of us in our impoverished honor culture that we could honor people we hate, or at least tolerate the honoring of people we hate. But it’s possible. It’s also necessary if we want our ideological opponents to respect our civic heroes.

If we are serious about the current ethical standard that holds chattel slavery, systemic murder of native peoples, lynching, segregation and rape to be illegal and unacceptable practice, what could possibly be gained by continuing to honor figures publicly, who proactively supported or participated in any of the above? That the United States was founded on what we now consider crimes against humanity makes any honest honoring of many in our pantheon highly problematic. The systemic white washing of the abhorrent behaviors and positions of these figures is de facto evidence that we know something is deeply amiss, which we do not want to address (see Princeton’s blemish free rendering of Wilson for example). If we thought that accomplishments easily outweighed ethical problems, we would already have an asterisk/plaque method in place, as suggested by LK Mcpherson above (no doubt to highlight the hypocrisy of these “balance” and “erasure” claims in the first place).

What is really at stake behind all the hand wringing about freedom of speech, balance and erasure, is instead an honest rendering of American history and national identity. It would be simple and just enough to hold any public honoree to the standards set above, yet still speak openly and academically about those figures that fall short in terms of both their accomplishments and crimes and/or misdeeds, and/or follow the asterisk/plaque method suggested by McPherson, thus eliminating any claim at erasure. There would also be many figures, who still pass muster, including MLK, whose plagiarism problems clearly merit no consideration in a conversation that concerns crimes against humanity. The fact that this standard would still eliminate major American historical figures, Jefferson and Wilson included, from public honor is clearly difficult for people to accept. But difficulty is not an ethical position, and there is literally nothing to be lost by this redress, but symbols, who do not represent our purported values, unless of course we are saying that they do, which is the real ethical danger of objection here.

Time for all philosophy departments to get rid of their busts of Plato and Aristotle.

I think we do need to recognize the racism of a lot of philosophers. It would probably be better if we were more clear-eyed on this issue. That doesn’t invalidate the intelligent things these philosophers had to say, but we should accept that they, historically speaking, also justified atrocities and crimes against humanity, and often times played a large role in serving as “moral authorities” to point to for such justification.

And there is George Washington University, an entire university, and a very prestigious one named after yet another white male slaveholder. And Georgetown? How about the entire city in which these two universities reside? We don’t even have to adjust any standards beyond those of George Washington himself, who recognized the evils of slaveholding even in his own writings, and yet still held slaves. So we have a white supremacist segregationist with sincere beliefs who founded various parts of a university (Wilson), versus an actual slaveholder who was the worst kind of racist by his own (later in life) standards, where the entire capital city and many of its monuments and yes, universities, are explicitly honoring. Surely history has not been kind to those who have destroyed the iconography of its ancient and not-so-ancient past even when it was done from very legitimate grievances over slavery, colonialism, and persecution. Wouldn’t it be better if under every display of Wilson was a permanent plaque stating the whole of their racist actions and how it affected the institution? At least then Princeton would have to live with the open and public knowledge that they had been an elite-white segregationist institution rather than just having it erased from public view.

Maybe if the plaque was as big as the statue, that could be an effective balancing, i.e. a giant sign right next to the statue that says “this person was a horrible racist who committed atrocities and crimes against humanity”. But, wouldn’t this just highlight the absurdity of having their statue up in the first place? We don’t need to honor and glorify these people in order to know our past.

I am hoping against hope this is a sarcastic comment. Either way, Poe’s law in action.

Unlike GWU and Washington, DC, Georgetown is the name of the town established in Maryland in 1751.

It is not named after George Washington.

Where does all this leave the US flag?

That’s a good question though it seems like the American flag is not quite in the same category as displaying a statue of a specific individual who took an active role in an atrocity or crime against humanity. The flag serves a functional purpose for designating a national identity, which is significantly different than a statue of honor which serves primarily to glorify the individual (who likely ought not to be glorified). An American flag can simply designate that you are American soil. That doesn’t mean you have to be proud of everything that has occurred here, whereas a statue is erected explicitly out of honor (you don’t put up statues of widely recognized historical villains – you tear them down).

It could mean that, but it symbolizes more than that, unavoidably. To many native Americans, I would imagine, the US flag would symbolize genicide and land appropriation; to many black Americans, it would symbolize slavery. I’m not sure you can avoid this by choosing to interpret it differently.

This is not to say that all US flags should be removed, but I’m curious what people think.

True, and I don’t think we should value nationalism anyhow.

I don’t quite know what you mean by “nationalism”. Wikipedia defines it as “strong belief that the interests of a particular nation-state are of primary importance. Also, the belief that a people who share a common language, history, and culture should constitute an independent nation, free of foreign domination.” Do you mean both of those? Why do you think flying the US flag requires a valuing of nationalism?

I’m not sure we should accept the assumption that the purpose of memorials to famous people is to honor them. It would seem to me that their much more important function is to signal the values that a society, or the institution that put them up, endorses. So it’s not really the moral character of a person’s actual life that matters, but what they stand for in the eyes of people who see their statue now. Figuring out what someone primarily stands for is, of course, not always an easy task, but I think that’s the better criterion to shoot for. So I think, on that test, Jefferson Davis and John C. Calhoun are obviously out because the main thing that they did that people associate with them now was defend the right of southern white people to own other human beings. I think George Washington is probably in on this criterion because, even though he was a slave-owner, the main thing people associate him with is independence, which we still value. I think Thomas Jefferson and Woodrow Wilson seem to be in more of a gray area. Racism isn’t the first thing I associate with either of them, but it seems like for a lot of people it is (see the photo above).

Sure, but the main thing people associate with Columbus is “discovering” America. I was even taught, at an elementary school in one of the most educated suburbs in America, that he “discovered” that the Earth is round. Unbelievable! There should not be a Columbus Day, and there wouldn’t be if future, better educated children associated him with the truth of his atrocities of genocide and slavery, rather than the nationalistic lying propaganda we associate him with today. Similarly, “we” associate Washington with liberty and not slavery because that’s what we’ve been taught. Let’s teach our children a proper understanding of American history where they learn that Washington, for example, owned slaves, and would have had good reason to know this was horrendously morally wrong, but did so anyhow. Then when our children know the truth about the past they might have different associations with these figures and wonder why we sing high praises to them.

I think it’s a mistake to get too focused on the moral status of the individual being honored. These aren’t protests against Thomas Jefferson, Woodrow Wilson, etc. These are protests against the honoring of those individuals. I think the question isn’t so much, “How best should we condemn Jefferson for owning slaves?” but instead, “What does it mean to honor Jefferson, in this day and age, given where we have been (as a country / a university / individuals), and where we want to go?”

In other words: note that the United States has never really done enough to acknowledge the horrible wrongness of slavery. The horrific system of slavery was replaced with a horrific system of Jim Crow laws was replaced with a horrific system… There have been no reparations; there have been no truth commissions; there has been no restorative justice. There has been no true reckoning of what the United states, as an entity, and what individual persons within the United States, did.

It is in this context that we see protests. Students are angry, why? Not, I suggest, because Thomas Jefferson owned slaved (he’s long dead, all the individuals he wrongfully held as slaves are dead), but because he is honored in an environment in which the wrongs he committed have never truly been acknowledged. He is honored in an environment where the hard moral work of making amends has not been done. He is honored in an environment where we still have to work to affirm that black lives matter.

When you die, the money you leave can be used to construct a statue in your honor, yes… but only after your remaining bills have been paid. These figures never had their ‘moral bills’ paid, if you’ll accept the metaphor. We never did the hard work of making up for the wrongs they committed, and we never did the hard work of truly analyzing and correcting the surrounding social/cultural environment in which those wrongs were so easy for them to commit. These protests are to make that apparent: it is deeply problematic for someone to put time and energy and resources into honoring an individual when that individual’s wrongs are left unresolved.

What would it mean at this point to acknowledge the wrongs that Jefferson committed? Certainly no one is denying that he owned slaves. Nor is anyone denying the counterfactual that were Jefferson a person living in the 21st century, he would be wrong to own slaves. Plenty of people freely admit that he was wrong to own slaves in the late 18th century (although then you get into the legitimately prickly areas of moral standards changing through time). What is it to make amends for the wrongs of a historical figure? I don’t see how (to take recent examples), having a school administrator condemn racism (and apologize on behalf of…somebody) and even committing to hiring more minority faculty and staff has anything to do with “paying the moral bills” of Thomas Jefferson or whomever.

It seems to me that it is quite important to distinguish the historical person who a statue might represent, from what the person itself is a symbol of and which is arguably the reason to honor the person.

This is not to say that the often awful deeds some of the people we honor did, should not count against putting up a statue of them, but it is to say that these deeds should be relevant in so far as they contribute to the person’s function as symbol for something we would like to hold up as important.

So I guess for example Jefferson is (supposed to be) a symbol for independence, freedom, and (to an extent) human rights for his work on the declaration of independence and other work he did, and that is one reason why statues of him are put up.

Now the debate we should be leading, is whether his stance and probably more importantly his actions concerning slavery, serve to undermine the ability of him serving as such a symbol. My hunch is that maybe they do, because the actions are so obviously contrary to what the person is supposed to be a symbol of. But this is not obvious and it very much depends on public use and perception of this symbol. In any case it is not enough to just note that someone we honor did something bad, or that he was a bad person to justify that one ought not to honor that person as a symbol for something we consider good and important. We have to show that the role of the person as symbol for some good is seriously undermined by his or her deeds.

This case should also be distinguished from the obviously bad cases where some person is a symbol for something we justifiably consider as bad. I suppose there are people who honor people for very wrong reasons, and I guess here an argument against putting up public statues is fairly easily made.

In any case, the debate would benefit from some more distinctions and a more nuanced view of the function of honoring people, or putting up statues, and the many levels of normative considerations that may play a role.

It seems to me there is a distinction to make in this regard. When you speak about the “reasons for honoring a person” I think this reflects a feature of the practice of honoring. It is not merely that we honor a person for all of the beliefs and values they have. When we honor a person we are not committed to praising everything they have done in the past. Rather, we are honoring the person for something specific they have done (e.g., “the Academy Award for best actor goes to…….”) So there is a distinction between “honoring” and “honoring for” that is being elided in these discussions. The protestors of Jefferson want to suggest that by erecting a statue we are thereby committed to praising everthing that Jefferson has done in his life—that the University of Missouri thereby supports slavery. But the makers of the statue were praising Jefferson for particular deeds and values he had. So to suggest that now (in the eyes of certain groups) Jefferson’s statue represents something entirely different is to mischaracterize the intentions behind the statue. To honor someone for X does not imply that we are committed to supporting other things this person has done.

It’s not clear to me why these debates move so quickly without the input of historians. I, like the above commenters, have some pictures of what some of these historical figures did and I could trot them out as truth as well…but it seems to me that if the question is about what these figures are (not what they represent), then we need to consult the field that has been giving sophisticated accounts of these figures for centuries. That’s not to say that non-historians cannot develop accounts of their own, but it is to say that I highly doubt that non-historians are capable of coming up with accurate accounts without any input from the specialists or at least the evidence that the specialists have discovered and interpreted.

And if one objects that the matter at hand is a matter about what these figures represent, then I say we have our arguments/debates amongst one another about that…and then we take a vote. If Jefferson or whoever represents what we (qua our majority) want to honor, then keep their statues up. If not, then vote as well on the course of action that we should take regarding the statues (perhaps add a plaque or perhaps drag the statue through the streets Saddam style). Even if some group thinks that the statue represents something they abhor, it does not follow that the populace as a whole must take the statue down. If that group cannot convince the others, and that group is a minority, then they will have to wait until they can get more on their side. Now, I think the main issue with this route is that it is hard to identify the relevant voters. In the case of the naming of Washington DC, I think the relevant voters are the country as a whole. In the case of a statue on a particular campus, it is much harder to say.

“It’s my estimation that every man ever had a statue made of ’em was one kind of son of a bitch or other.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rdMbjqAL6T8&feature=youtu.be&t=42m8s

I don’t think we’re going to be doing Jefferson or Wilson any harm by removing statues or plaques or renaming things. So what is it that the rest of us have to lose? Dan Demetriou seems to suggest we might lose the ability to incentivize current leaders to support democratic values and institutions; but is that really what we’re doing if we take back those honorifics from public figures precisely because they supported anti-democratic institutions like slavery and segregation?

I would also suggest that we tread carefully with the idea of measuring the good vs the bad to see which outweighs the other in evaluating these figures. Do we really want to speculate from our armchairs and the safety of historical hindsight on whether anyone’s public contributions “outweigh” holding other human beings as property? Such weighing also typically leaves unanswered the questions of “outweighed for who”? Whatever benefits democratic institutions may provide to contemporary Americans, they carried little weight for Sally Hemmings or Jefferson’s other slaves.

Derek, that’s a great quote and I’ll be sure to remember it! Let me reply to this: “Dan Demetriou seems to suggest we might lose the ability to incentivize current leaders to support democratic values and institutions; but is that really what we’re doing if we take back those honorifics from public figures precisely because they supported anti-democratic institutions like slavery and segregation?”

To this I say, yes, but to support anti-democratic institutions like slavery and segregation fully (e.g., a Genghis Khan of America) is different from supporting some anti-democratic institutions in some ways, and supporting democratic institutions in other ways. The slaveholding founders such as Washington and Jefferson fall in the latter camp.

“I don’t think we’re going to be doing Jefferson or Wilson any harm by removing statues or plaques or renaming things. So what is it that the rest of us have to lose?” Prescinding a bit, the question is, “What does it matter to dead people if we stop honoring them?” I guess my answer is parallel to respecting inheritance wishes or property rights: if you take away the honor of those who could have ruled us but didn’t, then those who can rule us now but do not will see less and less reason to forsake present benefits for future rewards of legacy. We create the secular afterlife of the great, and if they see no promising afterlife, that’s just one less reason they have to behave themselves.

In analyzing my own moral instincts, I’m finding that hypocrisy and harm to others play a significant role. I find it repugnant — and unnecessary — to honor folk who did significant harm to others, be it Hitler or Yale. But I also find it somehow equally repugnant and perhaps slightly more despicable to honor the hypocrites, i.e., folk like Jefferson and Wilson who said one thing and then followed an opposite course of action in dark rooms behind closed curtains. Surely the fact that they were such progressive and careful thinkers revealed that they KNEW the horror of their actions, and were pursuing them with open minds and dark hearts? Deliberate harm and indifference is not a mere mental illness or “moral blemish.”

Part of the problem is that it is (in my view) impossible to separate the person from the ideals they are being used to represent. A further problem is that everyone whom we may wish to honor will, in virtue of being human, have a laundry list of deeds that would be embarrassing to make public.

Some here have suggested pardoning or softening our assessment of certain figures if the views and actions of theirs that we find repugnant were statistically widespread in their day and age. The point being, I take it, that the ideals that the honored individual has come to represent are valuable enough to continue the honoring. While I think this makes some sense, I wonder why we don’t just give up the practice of honoring individuals in the first place.

We have a lot of monuments dedicated to Ideals and Concepts that don’t represent specific individuals (the statue of liberty, the thinker, etc). Unless there is some special value to honoring a specific human individual, it seems like we can honor ideals just fine without picking a specific named person. I think this shows us that the issue of ‘honoring the values the person represents’ is really a red-herring.

Don’t forget the piece of shit Jeffrey Amherst, after which among many others both the MA town and the liberal arts college are named.

“P.S. You will Do well to try to Innoculate [sic] the Indians by means of Blankets, as well as to try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execrable Race. I should be very glad your Scheme for Hunting them Down by Dogs could take Effect, but England is at too great a Distance to think of that at present.”

The great thing about this is that US history is fundamentally dishorable. This is shown by the ‘Jeff’ mascot of Jeffrey Amherst who suggested giving smallpox blankets to Native Americans, by our slaveowning, slave-raping presidents and founding fathers and many other things. We have a chance to reckon with history, finally.

It amazes and mystifies me why anyone would defend honoring any of these people. This is a shameful, disgusting, terrifying history of brutality that we are the beneficiaries of and the sooner we renounce it, the better.

If we’re going to do this, let’s also make a point of not honoring morally evil philosophers by inviting them present at conferences and stand for the profession. Not to do so would be clearly hypocritical.

Someone who habitually does something that is wrong, and that people recognize or should recognize as wrong today, and that is likely to be considered very, very wrong by future generations despite being generally winked at in today’s society is surely a bad person.

Driving a car or flying in an airplane when these things are not absolutely necessary, or habitually eating food obtained by reliance on the world-destroying fossil food industry or created in the first place by unsustainable farming practices when one could do otherwise with sufficient effort, or who wear clothes and use consumer products produced by sweatshop or slave labor overseas, is surely morally wrong now, will be seen as very, very wrong by those living in the post-fossil fuel age in all likelihood, and is the sort of thing we recognize but choose not to eradicate from our lives now. Yes, we have moved away from having slaves in our home or down the street. Instead, most of us rely on slaves elsewhere to make our things.

Therefore, more or less none of us should be honored by invitations to speak at philosophy conferences. A very few people are exempt from this and should be so honored, though.

Though presumably they won’t attend, since they’d probably have to fly to do so.

Exactly, David.

We are curious creatures, aren’t we? We all know that we’re doing and allowing some very bad things on a daily basis: supporting the trashing of the planet through our purchases, even when we try to make ourselves feel better by purchasing products that do 10% less evil than the ones most people buy; doing little or nothing to prevent the huge suffering of impoverished people worldwide: actively facilitating and supporting slavery and inhumane working and living conditions around the world by purchasing the goods they supply; living great lives thanks to United States foreign policy, which we know leads to horrible conditions and endless wars in most countries, and yet not feeling too guilty about it because we sign statements against the latest war or invasion (which we know from experience will do nothing to stop the wars or invasions or make anything better); using up the resources of the world at an alarmingly fast rate, in a way that is guaranteed to plunge all future generations and quite possibly even the last years of our own generation into darkness and chaos forever. We will surely be remembered forever as the worst assholes in world history for collectively doing all these things, and we kind of know that. But it doesn’t really stop us, or at best it leads us to make largely futile token gestures against it.

Meanwhile, we want to feel morally superior to others, so we have to turn our attention to things we’re not implicated in. The enslavement of children and adults of less fortunate races worldwide in huge numbers, who make our clothes and other things for us? That’s morally important, we know, but surely not as important as the moral case for renaming a college that was named after people who were involved with slavery over a hundred years ago or who said racist things. Because for all that we’re doing to support the enslavement of other races across the world, at least we’re not doing it right in our homes and saying it’s OK! So the slavery of people that happened years ago, right on US soil, is something we’re all innocent of. That makes it a great thing to attack, even though it won’t rescue a single 18th or 19th century slave from any harm, and even though we could use that same amount of energy to address the slavery of other races we’re actually complicit in. That’s too uncomfortable.

Making spaces psychologically ‘unsafe’ through saying things that university students (mostly from well-off families) find offensive is another evil we love to fight in our ostentatious ways. But making the workplaces of the countless impoverished people who make our goods physically unsafe in order to squeeze more profits out of the system? Well, that shouldn’t be what we philosophers discuss as much, should it? There’s much less fun riding that hobby horse, since we all know none of us are exempt. Sexist remarks, or remarks deemed to be sexist, are another great one. Is it evil? Of course. But how to weigh its evil against the evil done around the world on our behalf on a daily basis? How to weigh it against the soldiers and civilians needlessly maimed, tortured and killed in needless wars and slaughters? That’s easy. We all know the wars that are fought and the slaughters performed are the cost of our having the things we like. Making sexist or putatively sexist remarks, however, is we can be totally innocent of. So let’s allow the horrors of the world elsewhere to unfold as they do, and with blood dripping from our hands repeatedly engage in the performance of pointing at the evildoers at home who violate taboos by saying inappropriate things.

I do not think that we should honor historical figures. It gets in the way of evaluating history as objectively as we can. Honoring historical figures turns them into symbols.

I don’t see why we can’t have it both ways. What’s wrong with saying, after being invited to check out some statue, “Man, fuck Thomas Jefferson [judgment of dishonor concerning the man, the topic of history], but yeah, I see the point of the statue [judgment of honor is still appreciable/understandable concerning Jefferson the symbol, the mythical Jefferson.]” Is such a person making a mistake? Do they need philosophical correction? It seems like each of the attitudes holds up a different standard for posterity. Making room for both encourages a desire to be moral in one’s personal life qua individual person and to leave a good civic legacy qua public servant. It might seem like Columbus would pose a problem for this idea, but there, it seems like the very deeds he was traditionally honored for turned out not to have been at all like the way they were in our whitewashed histories. The mythical explorer and discoverer of new places and peoples was in truth a conquester and murderer of those same people and places. The mythical Columbus was directly undermined. This may not be a desirable stance to take for another reason, though. It puts someone in a difficult position if they feel unsafe or unwelcome in a place in which such a statue is prominently displayed. The correct response on this picture would be to say “It’s a statue for the symbol, the myth, and not the man. His terrible deeds are not what we encourage and not what we understand as a community by the statue. You shouldn’t understand it that way.”

Just so we’re clear: even by the stringent standards people have put forward, Lincoln is going down.

(1) He was directly in favor of the genocide of native Americans (look up his correspondence with Sherman). He also ordered the largest mass execution of people in history… which happened to be of native Americans.

(2) He was a war criminal by any reasonable standards: he approved of direct attacks against civilian targets. The total war tactic used by the Germans in WWI? Yeah. They got that from consulting with U.S. generals from the Civil War.

These alone should be more than enough to disqualify him right alongside Jefferson and Washington. It explicitly meets the crimes against humanity criterion. But just in case you aren’t convinced, know also that:

(3) He didn’t free the slaves; Congress did. The Emancipation Proclomation was a patent political maneuver. It only “freed” states in the States in rebellion, and even promised those states slavery in perpetuity if they rejoined the Union.

(4) He was an outspoken white supremacist, consistently saying things about how African Americans can never be allowed to hold office, and how saying whites and African Americans were equal is like confusing a chestnut horse with a horse chestnut. His primary plan was to send the freed slaves to Liberia because he did not think they had a place in America. So, ironically, the statement “if it were up to him I wouldn’t be here” in one of the above notes is probably more true of Lincoln than it is of Jefferson.

(5) He suspended the writ of Habeas Corpus so that he could imprison journalists who criticized the war.

(6) He was a corporate lawyer above all else, and much of what he did legally paved the way for the excessive powers corporations now enjoy.

I’m fine with taking down statues. The American people are hopelessly ignorant of history anyway. Most in my generation probably can’take even tell you who Jefferson is, or what the Civil War was about. I just can’t stand hypocrisy. Nothing of Lincoln’s positive achievements even remotely compare to those of Jefferson or Washington. His sole achievement (see (3) above) is that he presided over the war that still outstrips the number of American casualties for all other wars including both WWI and WWII… and it was fought with freaking muskets! This is in spite of the North having ludicrously more manpower and resources than the South, and in spite of the fact that he essentially had dictatorial power. There’s a word for this: incompetence.

Abraham Lincoln does not need me to defend him from these charges (which range from the overstated to the wholly meritless), but I’ll content myself with the following comment about number (1):

The standard scholarly edition of Lincoln’s writings is online:

http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/

Given the gravity of the accusation, I don’t think it’s unreasonable to ask for a reference to a specific passage in which he proved himself to be “directly in favor of the genocide of native Americans”.

You are quite right that Lincoln does not need you to defend him. He’s as dead as a doornail, and–unless you’ve got a time machine stashed somewhere–history is immutable. It is only your opinion about Lincoln that needs defending.

On Lincoln’s relation to native Americans: https://books.google.com/books/about/38_Nooses.html?id=oEjAgzFHImwC

Or you can take a Native American perspective seriously: http://www.unitednativeamerica.com/hanging.html

If you want something only from the source you listed (which doesn’t include all of Lincoln’s correspondence), here’s an excerpt from Lincoln’s 1863 Message to Congress ( http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln7/1:77?rgn=div1;sort=occur;subview=detail;type=simple;view=fulltext;q1=indian# ):

“The measures provided at your last session for the removal of certain Indian tribes have been carried into effect. Sundry treaties have been negotiated which will, in due time, be submitted for the constitutional action of the Senate. They contain stipulations for extinguishing the possessory rights of the Indians to large and valuable tracts of land. It is hoped that the effect of these treaties will result in the establishment of permanent friendly relations with such of these tribes as have been brought into frequent and bloody collision with our outlying settlements and emigrants.

Sound policy and our imperative duty to these wards of the government demand our anxious and constant attention to their material well-being, to their progress in the arts of civilzation, and, above all, to that moral training which, under the blessing of Divine Providence, will confer upon them the elevated and sanctifying influences, the hopes and consolation of the Christian faith.

I suggested in my last annual message the propriety of remodelling our Indian system. Subsequent events have satisfied me of its necessity. The details set forth in the report of the Secretary evince the urgent need for immediate legislative action.”

As the annotation notes, the legislation Lincoln was referring to at the end was proposed by none other than the openly genocidal Gov. Ramsey himself: http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsb&fileName=038/llsb038.db&recNum=1246 . In essence, it proposed to give Lincoln nearly boundless executive power to relocate Native Americans at his will. Of course, Lincoln doesn’t explicitly say that he wants to kill off all Native Americans in front of congress. Here’s a fun little exercise: try to find a quote in one of Hitler’s public political speeches in which he explicitly talks about putting people in gas chambers and then burning their bodies in ovens.

Second, the fact that the Union army under Lincoln’s command targeted civilian populations with the explicit intent of causing starvation is simply indisputable. Would you deny the existence of Sherman’s march to the sea, or Sheridan’s torching of the Shenandoah valley? Do you think Lincoln knew nothing about these major campaigns conducted by his major generals? Here’s a letter of Lincoln congratulating Sheridan for his campaign in the Shenandoah: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln8/1:144?rgn=div1;sort=occur;subview=detail;type=simple;view=fulltext;q1=sheridan;q1=sherman . Here’s a similar letter of Lincoln congratulating Sherman on his march to the sea: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln7/1:1166?rgn=div1;sort=occur;subview=detail;type=simple;view=fulltext;q1=sheridan;q1=sherman . There is no rational defense for this. Deliberate destruction of civilian property with the explicit aim of causing starvation = warcrime. Period. How can you hope to condemn America’s contemporary actions overseas when you celebrate someone who deliberately sent the U.S. Army after its own civilians? Or are we supposed to be finicky about which crimes against humanity we count as disqualifying? So even if you don’t buy the idea that Lincoln supported the gradual eradication of Native Americans, this is still enough to disqualify him from being honored if judged by the same criteria as Jefferson and Washington.

Now, with that out of the way, here are some more fun quotes:

The Suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln5/1:957?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

Abject waffling on whether the emancipation proclomation was worthwhile: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln5/1:933?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

Memorandum to Maryland slaveholders worrying about whether the fugitive slave act was being enforced, assuring them that he would “would take their representations into consideration, and see that no injustice was done”: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln5/1:500?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

Memorandum on recruiting slaves: “To recruiting slaves of loyal owners without consent, objection, unless the necessity is urgent.” http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln5/1:736?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

And the pièce de résistance: Lincoln’s “Address on Colonization to a Deputation of Negroes”: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/lincoln5/1:812?rgn=div1;view=fulltext

This was a speech Lincoln gave to a group of African Americans he had called expressly to convince them to sign on to colonize south American where they can mine coal. That’s the context. Not a vague speech given at a political rally in a slave state, but rather a direct attempt to enact policy that he clearly believed in. Here is a fun little excerpt:

“But even when you cease to be slaves, you are yet far removed from being placed on an equality with the white race. You are cut off from many of the advantages which the other race enjoy. The aspiration of men is to enjoy equality with the best when free, but on this broad continent, not a single man of your race is made the equal of a single man of ours. Go where you are treated the best, and the ban is still upon you.

I do not propose to discuss this, but to present it as a fact with which we have to deal. I cannot alter it if I would. It is a fact, about which we all think and feel alike, I and you. We look to our condition, owing to the existence of the two races on this continent. I need not recount to you the effects upon white men, growing out of the institution of Slavery. I believe in its general evil effects on the white race. See our present condition—the country engaged in war!—our white men cutting one another’s throats, none knowing how far it will extend; and then consider what we know to be the truth. But for your race among us there could not be war, although many men engaged on either side do not care for you one way or the other. Nevertheless, I repeat, without the institution of Slavery and the colored race as a basis, the war could not have an existence.

It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated. I know that there are free men among you, who even if they could better their condition are not as much inclined to go out of the country as those, who being slaves could obtain their freedom on this condition. I suppose one of the principal difficulties in the way of colonization is that the free colored man cannot see that his comfort would be advanced by it. You may believe you can live in Washington or elsewhere in the United States the remainder of your life [as easily], perhaps more so than you can in any foreign country, and hence you may come to the conclusion that you have nothing to do with the idea of going to a foreign country. This is (I speak in no unkind sense) an extremely selfish view of the case.”

A classic piece on the ethics of honoring people is G.E.M. Anscombe’s “Mr. Truman’s Degree” (1956). The piece argued that Truman’s decision to target Japanese civilians with nuclear weapons should disqualify him from receiving an honorary degree from Oxford. Two relevant quotations:

“An honorary degree is not a reward of merit: it is, as it were, a reward for being a very distinguished person, and it would be foolish to enquire whether a candidate deserves to be as distinguished as he is. That is why, in general, the question whether so-and-so should have an honorary degree is devoid of interest. A very distinguished person will hardly be also a notorious criminal, and if he should chance to be a non-notorious criminal it would, in my opinion, be improper to bring the matter up. It is only in the rather rare case in which a man is known everywhere for an action, in fact of which it is sycophancy to honor him, that the question can be of the slightest interest.”

“I vehemently object to our action in offering Mr. Truman honours, because one can share in the guilt of a bad action by praise and flattery, as also by defending it.”

Hegel’s “Who Thinks Abstractly?” (1808) is also relevant. A passage that gets the main idea across:

“A murderer is led to the place of execution. For the common populace he is nothing but a murderer. Ladies perhaps remark that he is a strong, handsome, interesting man. The populace finds this remark terrible: What? A murderer handsome? How can one think so wickedly and call a murderer handsome; no doubt, you yourselves are something not much better! This is the corruption of morals that is prevalent in the upper classes, a priest may add, knowing the bottom of things and human hearts….

“This is abstract thinking: to see nothing in the murderer except the abstract fact that he is a murderer, and to annul all other human essence in him with this simple quality.”

I might think that Alasdair MacIntyre’s old, but still interesting, essays on “How to think about Lenin” and “How to think about Stalin” (if I’m remembering the names correctly) in his book, _Against the Self Image of the Age_ might be of some use and interest to people trying to navigate these questions. I found them quite useful in thinking about, say, taking down statutes of Lenin and Stalin, or re-naming Leningrad or Stalingrad, when I lived in fairly early post-Soviet Russia.