Answering the Taxpayers

I am a professor of philosophy at a public university. What is the value of philosophy to the taxpayers who subsidize my teaching? Philosophy is an abstruse and difficult field. Many of those whose taxes support higher education probably would have a hard time seeing the point of most philosophical debates. Why ask people to pay for discussions of seemingly arcane and incomprehensible topics? Besides, does a field like philosophy have any quantifiable or objectively measurable value, or do its putative benefits seem vague and elusive?

Further, don’t philosophers raise troublesome questions and defend positions that might undermine the bedrock convictions of the people who subsidize their salaries? Why, for instance, should conservative, God-fearing people be willing to help support research and teaching that might lead their children to liberalism or atheism? Shouldn’t professors instead have the responsibility of inculcating the values of the people who help pay our salaries? I think that too many academics dismiss such questions with a condescending smirk or a dismissive shrug. Yet these are serious questions and they deserve direct and convincing replies.

Keith Parsons, a professor of philosophy at University of Houston – Clear Lake, takes up the task of justifying to taxpayers why public universities should offer philosophy courses in a column for the Huffington Post entitled, “What Is the Public Value of Philosophy?”

The short version of his answer is that philosophy, by presenting students with potentially unsettling challenges to their beliefs, teaches students “how to think.” He contrasts education with “indoctrination” — teaching students “what to think.”

It seems to me that the strongest challenge to philosophy’s spot in the university curriculum is not from those who seek to indoctrinate college students, but rather from more seemingly practical courses of study, such as STEM fields or business majors. Further, it is silly to think that the professors in those fields are not teaching their students “how to think.” The study of sciences and business areas are full of challenging and surprising ideas that play a role in teaching students how to think. While it may be true that “an education in philosophy gives a person the tools to reflect critically, think logically, [and] make rational decisions,” I think philosophers should guard against pretending they are the sole providers of these goods.

How would you answer the taxpayers?

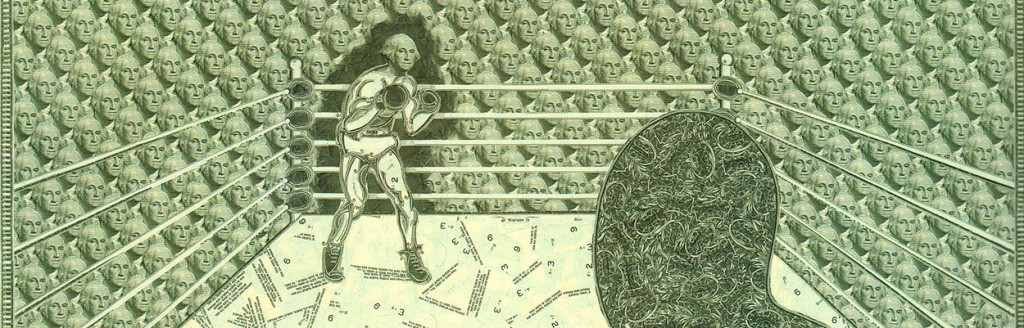

(image: dollar bill collage by Mark Wagner)

Approach 1: simply point to all the instances of poor reasoning that make the world worse than it would be if the reasoning were more careful. For some good examples, you might take a look at Bishop & Trout 2005 and Trout 2009. Then say, “Philosophers (and psychologists) are trying to improve this part of the world.”

The problem with approach 1 is that it seems that not all philosophers are actually trying to do this. Some just teach the history of ideas. Others care very little about teaching and more about tenure-getting activities like publishing things that are not accessible to their students (given the incentive structure, I can hardly blame them). And some philosophers seem to be against this mission(!) — e.g., see those who wrote critical book reviews of Bishop & Trout 2005.

So it’s not clear that philosophers can, across the board, appeal to approach 1.

So what are the other approaches to justifying the claim that philosophy classes are worth their public funding?

when I see how philosophers respond to academic matters having to do with issues like hiring standards and or judging the quality of each others work I see no signs that they are better equipped than lay people to address such daily issues.

The question about the public value of philosophy is a great one that we should all take seriously. But I would caution against framing the question as “How should we answer the taxpayers?” unless it’s obvious that it’s primarily the taxpayers as such who are owed an explanation (rather than, say, the other potential recipients of benefits paid for by tax revenues). I think this is far from obvious.

Better to address “the citizens” rather than “the taxpayers”, I would say.

There was a great OpEd in the Washington Post recently arguing that the Liberal Arts are necessary for successful STEM: http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/why-stem-wont-make-us-successful/2015/03/26/5f4604f2-d2a5-11e4-ab77-9646eea6a4c7_story.html

I don’t think we should completely disregard the point that philosophy departments are well-suited to offer classes that bring into relief the general characteristics of good reasoning. Undoubtedly students learn how to reason well in other classes, but philosophers are well-positioned to talk about (and not merely in logic classes) why good reasoning is good. I agree, though, that this is unlikely to be wholly satisfying. My sense is that, ultimately, philosophers have to say that the reason philosophy in the university deserves public support is not merely because it teaches students to think about any old thing, but because it offers students the opportunity to learn how to think about its subject matter, i.e., philosophy. Two points in this vein come to mind, though I’m sure there are more. First, much of philosophy is concerned with normative aspects of what we ought to do (ethically, politically, legally) – it gives serious attention to these questions, in ways not mimicked in other disciplines. In a democratic society, it seems important both that there is a recognition that serious attention to normative matters (as such) is possible, and that people know how to reason well with respect to normative matters. Is equality a threat to liberty? What kind of equality do we owe each other? If the people are responsible for ruling, it is at least valuable that there is a sense of how to think about these questions. Reading economics alone will not help. Second, concerning philosophy more generally, public universities have egalitarian functions: they offer access to learning that would otherwise be unavailable. Many students attending public universities could not afford a private one. Many students, not just the financially privileged, wonder about what the mind is or how consciousness is possible, the freedom of the will, how and what we can know, what it is for an act to be right or wrong, a thing to be good or bad, etc., etc. Many students think these are very important questions (consider that there are many popular intro. to philosophy classes). Philosophy is the discipline that takes these questions seriously. Without public universities supporting philosophy, we would live in a society in which a significant part of the populace would have quite limited to no opportunity to learn how to think well and seriously about fundamental questions which they regard as important.

A bugbear lurking in our professional shadows: There may be a set of things that philosophy provides to students in general at universities and colleges, something that is of enduring value which can help us to answer this question. The problem is that the provision of the things in this set will almost certainly require that professors be good, helpful, engaging and capable. Yet, ours is an academic culture in which graduate students will openly avoid teaching if they can, in which teaching is often seen as a burden or distraction away from our “real” activity, where some of our “top” departments hire people with barely a glance at their teaching dossier (two friends of mine recently hired by “top-20” schools had this experience). So even IF we are able to name the activities of ours which have public value, the citizenry would be perfectly justified in asking: “oh yeah, so what’s with the devaluation of those very activities in your upper ranks?”

This is a great question, and one that everybody who has ever written a grant application will (hopefully) have thought about. On a very general level society benefits from the research and teaching done in STEM fields by being given the means to attaining various ends: whether it’s curing your headache by taking some painkiller, or talking to a friend overseas by using a cell phone. I can’t speak for other areas of philosophy, but as far as my own research is concerned I think the answer is identical: we study means-end relationships. In STEM areas these means-end relationships are often causal relationships that are established experimentally. In philosophy these means-end relationships are often logical relationships that are established by proving a theorem or, more generally, by providing an argument.

To echo a few comments already made…

It’s a tough climb to say that philosophy uniquely teaches students how to think. Not only is the ‘unique’ part ripe for counterexamples, this line of argument runs the risk of undercutting vast swaths of the philosophy curriculum: if the public value of philosophy lies in teaching students how to think (insert political/social/democratic value of this skill here), then (publicly subsidized) philosophy curricula should center primarily around formal and informal logic. To put this point another way, this defense of the public value of philosophy risks favouring the ‘form’ of reasoning over the actual content of various philosophical theories/positions.

On the note of the content of philosophy, another tough climb awaits here. It’s just not clear to me that there is any public value in sharing with students tortuous debates about, say, whether I know I’m typing on a computer right now, or whether there is any sense to be made of how many could be one. It strikes me that this is the height of intellectual frivolity–that is, crucially, when ‘value’ here is being understood in terms of service to the public.

Perhaps these debates have value when this term is construed in other ways. And whether that’s the case is, I think, the really crucial issue here. I think we should be careful to not overlook the possibility that philosophy is at its core elitist and at odds with the public interest. Socrates’ execution and all that jazz.

Ask not what philosophy can do for you, but what you (dear citizen / taxpayer) can do for philosophy…!

Seriously, though. Philosophical (and other intellectual) inquiry is an intrinsically valuable human activity, and it would be a debased society indeed that placed no value on enabling and encouraging such scholarly pursuits. It enriches our culture, as ideas percolate in the academy and perhaps eventually “trickle down” into the general public’s understanding of the world and our place in it. It enriches the lives of students who get to partake in this distinctively valuable human activity — though, admittedly, some of them will appreciate this more than others. Some subdisciplines (e.g. applied ethics) have significant instrumental value (i.e. instrumental to bringing about morally better outcomes) in addition. All at no significant cost. What’s not to like?

I Richard Yetter Chappel’s final question. Perhaps our best strategy is to just pose this question: We ask the public to explain why philosophy is not valuable. In doing so, they will either (a) offer a philosopically rigorous argument or (b) not. Either response will demonstrate *some* of the value of philosophy. (i.e., If they argue well, we say, “Good argument! It seems like you are already enjoying the benefits of philosophical rigor.” If they argue poorly, we say, “Hmm…it looks like your argument could benefit from some philosophical rigor.”).

I agree with many earlier comments that this is a really important subject to discuss, and that the terms in which it’s posed matter a lot.

Briefly on the topic of teaching “how to think,” I would contend that “think” here doesn’t mean the same thing as “reason.” It also involves, among other things, the ability to identify unstated assumptions, formulate and compare competing explanations, draw novel connections among concepts, and restate arguments for conclusions with which you disagree. Drawing a justifiable conclusion from given premises is also important, but I don’t think logic covers everything that fits under “thinking.” Philosophy isn’t unique in teaching other thinking skills, but I think it does so particularly well.

On a broader issue, most of the comments so far have focused primarily on teaching as the valuable service that philosophy offers. I think that’s mostly correct and that any attempts to justify philosophy research activities on strictly return-on-investment grounds are probably ill-conceived. But I wonder if there’s another way to make the case that goes something like this: America is a great country. Great countries ought to produce great ideas (along with great art and great social achievements). Funding philosophy research is one good (although obviously not perfect) way to encourage the production of great ideas. Therefore, we should continue to pay people to do philosophy research.

By “great” in this argument I mean something like either “of world-historical importance” or “intrinsically valuable.” If we frame the hypothetical interlocutor as “citizen” or “patriot” rather than “taxpayer,” I think a version of this argument has some chance of being persuasive to some of them at least. One obvious shortcoming of this argument is that I think it comes off as kind of elitist, and Americans are well-known for our democratic tendencies. But in response to this, we might emphasize that in America, as a great *democratic* country, supporting the development of great ideas through public funding is especially appropriate (as opposed to most times and places, where great thinkers were either aristocrats or had aristocratic patrons). Not to mention that Americans are also well-known for our exceptionalist tendencies as well.

I’m not sure if this is a promising argument or not (practically speaking). I’m not even sure whether I’m convinced by it. But I think if you frame it in the right way, such as, consider how much we as a society spend on philosophers compared to say, iPad games or machines that let you exercise indoors, it can be persuasive. From a public choice perspective, I don’t think the case can be made that philosophy research is a necessary investment, but if you point out to people that most things we spend social resources on aren’t investments either, I think the argument that we can afford philosophy becomes easier to make.

In any case, I don’t know of any other good arguments in favor of public spending on philosophy research, so this one seems worth pursuing.

I’m not convinced studying philosophy teaches people how to think. Educational psychologists have been studying “transfer of learning,” and there’s now a lot of evidence that the assumptions upon which liberal arts education is based are false. Most students don’t apply what they learn in class outside of class. We don’t actually succeed in teaching student soft-skills. They don’t use the tools we give them for anything outside of writing essays. Etc.

Richard’s answer, that philosophy has intrinsic value, is more plausible. But then this still leaves open cost-benefit analysis questions: There are lots of intrinsically valuable things out there worth doing. Why spend tax money on this thing (philosophy) rather than on some other intrinsically valuable thing (e.g., public death metal concerts open to all)?

Further, even some things are intrinsically valuable (such as philosophy and death metal concerts), we have to ask why these things should be funded through taxes rather than left to individual choice. You don’t have to be a libertarian to think that not everything worth having or doing is permissibly done/best done by government.

Philosophical problems (often) aren’t all that special. They *are* the problems of the business and STEM fields, but these problems are the ones that can’t be solved using the established methods. If we did a better job at showing where our problems came from, in some sense their philosophical genealogy, then it would ground the philosophical work in a larger, more accessible program of research.

We might want to disambiguate two questions:

1) What public good(s) might be supported by the continued existence of philosophy?

2) What are the values of the public that the continued existence of philosophy supports?

It’s altogether possible that philosophy fosters public goods that are not actually valued as goods by the public at large. In many respects I think this is actually the case (cf. Rep. 514a-520a).

Following up on Jason Brennan’s skepticism about the intrinsic value argument, I’m just not at all sure that the ‘trickle down intelligence’ theory of the public value of philosophy holds much water at all. I think what we get instead when some pressure is applied to this line of thinking is a picture in which those who have the opportunity to make a living doing philosophy are bettered–perhaps ‘intrinsically,’ whatever that might mean–while those who are paid to do things that actually move the levers of our everyday lives have to make due with ‘mere’ extrinsic benefits.

It just strikes me as so unlikely that we’ll be able to get a strong case going for why what academic philosophers do is at all important to almost anyone but themselves. And that might be okay. But perhaps on someone else’s dime. To those working outside academic, it then shouldn’t be a surprise that tenure looks like a sinecure.

I like Marc Lance’s answer: philosophy as science’s start-up incubator: http://cs.nyu.edu/pipermail/fom/2007-March/011467.html

This answers the question “why should we have (professional) philosophy?” but maybe not directly “why should we teach philosophy in college?”

This discussion can go in many different directions, as evidenced from the variety of comments given above. I also have lots of opinions about this, but I’ll restrict myself to just replying to Justin’s worry in the original post.

“It seems to me that the strongest challenge to philosophy’s spot in the university curriculum is not from those who seek to indoctrinate college students, but rather from more seemingly practical courses of study, such as STEM fields or business majors. Further, it is silly to think that the professors in those fields are not teaching their students “how to think.” The study of sciences and business areas are full of challenging and surprising ideas that play a role in teaching students how to think. While it may be true that “an education in philosophy gives a person the tools to reflect critically, think logically, [and] make rational decisions,” I think philosophers should guard against pretending they are the sole providers of these goods.”

Here’s an argument by analogy. It is likely true that one can improve one’s athletic conditioning by solely participating in a particular sport. However, in spite of this fact, almost all serious athletes participate in activities that are focus particularly on athletic conditioning. STEM fields and business majors are to sports like football and basketball as philosophy is to activities like weightlifting and running.

If the analogy holds, then it relegates philosophy to a role that is supplemental to other intellectual activities. Philosophers are “personal trainers” of the mind. It may not be a particularly attractive view, and I personally hold philosophy to be intrinsically valuable, but if you’re encountering a demographic that is already hostile to the humanities in general and philosophy in particular, then this may be about as good as it gets as far as acquiring an entry point in the discussion.

Why is philosophy important? Because the Basic Questions in life–why are we here? Who am I? What is there? How ought I to live?–are fundamental to being human. To lost sight of the purchase these questions have on us, in favor of pre-determined answers implicit in STEM fields or neoliberal thinking is to dehumanize ourselves in a quite literal way.

And this thread is itself Exhibit A of the need for people – including philosophers in other fields – to read more political philosophy, both contemporary and historical. I like a good dorm room bull session as much as anyone, but Prof. Parsons and many of the commenters above are acting as though there isn’t already a huge literature on these issues. I guess it’s not surprising that people engaged in a discipline fundamentally shaped by the taxpayers of Athens deciding that they strongly disapproved of public philosophizing would be out of practice at engaging with the public, but reacting to the latest crises in higher education without drawing on the work of Mill, Dewey, and others in this long history of thought makes our responses shallower, less rigorous, and less persuasive than they should and need to be.

Here’s my real answer to this question (though I’m posting it anonymously, because I work at a state school and don’t ever want to be forced to make it convincing to a legislator). “The unexamined life is not worth living” is an exaggeration, but there is value in each person’s spending some time in his or her life thinking about philosophical issues. Philosophy classes provide a structured forum for that. (And as noted above, that forum should be made available to students beyond private-school elites.) Similarly, societies with sufficient resources should devote at least a small percentage of those resources to advancing their understanding of philosophical truths. Current Western capitalist democracies do so by paying academics to do philosophical research. The research part of our job is often basic research, much like basic research in physics, and is worthwhile for many of the same non-instrumental reasons. We and the theoretical physicists (and the dinosaur specialists, and the ancient historians, and…) are employed by our societies to figure s— out. And philosophers cost a lot less than particle accelerators.

I always wonder why giving people an opportunity to understand their civilization and the ideas it is founded upon is seen as frivolous. If we think that, we peel away about 95% of the humanities. Is there no point in learning history? Is there no point in reading literature? Is there simply no point in anyone being broadly educated at all? Do we want to preserve and share the best products of our civilization with that portion of the young who are becoming citizens? It seems that the idea is that there should be this special class of citizens–apparently those attending elite private schools where the taxpayer is not thought to pay-and the rest of the citizens who will have a bare bones education sufficient to please a corporation looking for a very precise set of skills. The starting assumption is that we do not as a society benefit from this diverse group of people with many different parts of knowledge who live together but instead we only benefit when people are given some particular skill for some very particular task, determined by the corporate needs of the moment. And everything’s radically changed in the world since whenever it was thought to be a good idea to establish universities to educate the populace–for some reason, no one quite says why–but there is some implication the internet is the change or some other type of technology. But so far most of what we have built society was built in a situation where many people were given these more robust educational options–and quite a lot of the journalism, technology, entertainment, art and science we want and depend on–was done by people with this education. And surely this relationship between their education and their abilities to create these things we want and need is not an accident. But for some reason: There is no point to whatever it is they learned and we should just scrap the whole project. No one says why. We can google everything? And google is like magic–it produces its own content?

I am genuinely conflicted about this. Part of me thinks that there is no possible justification that would satisfy the taxpayers demand, partially because taxpayers demands are fickle and irrational. In our country, taxpayers aren’t willing to endure a hike to pay for government-backed health care coverage for its citizens, but many are willing to shelling out millions for new sports stadiums. On the other hand, I believe the humanities are good for public education even if they tend go in odd directions.

Let us note that the complaint is not against philosophy but philosophy as it is taught in our universities. One has to wonder how effective and useful this form of teaching and learning is when it leaves itself open to this sort of criticism. It’s a criticism many philosophers would want to make and it does not represent a criticism of philosophy, just a particular approach to it that has turned out to be a dead end.

“The short version of his answer is that philosophy, by presenting students with potentially unsettling challenges to their beliefs, teaches students “how to think.” He contrasts education with “indoctrination” — teaching students “what to think.””

How unsettling are most philosophy classes? All the ones I’ve taken are pretty straightforward history-of-ideas courses. And based on the conversations on this website, a lot of philosophers actively try not to “unsettle” their students, if by unsettle you mean present ideas or arguments over which students might get offended.

Perhaps one way of remedying that is to increase teaching duties and remove motivation to publish. For the overwhelming majority of academics (and this goes for non-STEM fields in general) articles written vanish into the ether, never to impact the field.* Skillfully teaching a class reaches a lot more people and causes a lot more good than writing an article revisiting Aristotle’s notions on virtue in print. Maybe base tenure decisions on a combination of classes taught and some sort of qualitative assessment of one’s teaching ability?

* Actually, that’s true for a sizeable number of STEM academics, too.

What a ridiculous question.

Taxes don’t ‘fund’ academic philosophy or government spending at all (see Fraud 1 here: http://moslereconomics.com/wp-content/powerpoints/7DIF.pdf). The public don’t understand this, but why should we answer questions that only make sense from a position of ignorance?

Even if taxes did finance government spending, how do we know what the net revenue effects of philosophy are? Maybe it’s revenue-positive. Then the question would be: ‘Why should philosophers subsidize the taxpayer?’ Who knows?

If anything we should educate the public about how government finance works; there’s no justification for pandering to their ignorance.

Philosophy (in at least some of its areas) is a meta-discipline in which we reflect upon our capacities for knowledge and action. Such reflection can sometimes occur in the other disciplines themselves, but for the most part these other disciplines are usually busy teaching competences for attaining knowledge and performing actions rather than reflecting on these competences, their conditions, and their implications. Self-reflection of the kind philosophy pursues is a way in which people (and society) take themselves seriously by attaining some degree of self-understanding about knowing and acting. Surely, such self-reflection is a public good.

Peter Jones’s raises an important point. I’m reminded of many of the standard philosophical “proofs” of God’s existence. Even supposing the argument succeeds in showing that there must be a first mover, that is a long cry from showing that the first mover is an intelligent being of any sort, much less establishing the existence of the specific God the philosopher had in mind. Many of the forgoing defenses of philosophy don’t even begin to address whether and how the specific institutionalized forms of philosophy in question help to promote those values.

When we take those institutional question seriously, I think we should see that justification to the taxpayers is best thought of as a two stage process. One stage is convincing the tax payers that a university education is worthy of public support. The second is showing that courses in philosophy are an important part of a university education.

Better still, Derek, would be to show that philosophy produces results. This would require that those philosophers who scientists tend to consult put their own house in order. As for God, I would say that philosophical analysis shows that the idea doesn’t work, or not without a definition that most theists would see as heretical, the sort of definition that saw Al-Halaj crucified by his church. Philosophy is not a friend of commonplace religion, as many theologians have shown in an effort to get past the all the superstitious stuff. THIS is the usefulness of philosophy, as Bradley’s ‘antidote to dogmatic superstition’, and this seems to account for its unpopularity in some quarters.

It’s not unreasonable for the taxpaying public to ask these questions, and our answers had better be good if we want to continue to get funding in today’s climate. Fortunately for philosophy, we seem to have good answers to give.

While there are important social benefits to be gained from good philosophical research, it seems very implausible that the public really needs to fund all, or even a considerable fraction, of the research that it supports. Find twenty random philosophers at twenty random colleges or universities, and pick a random publication (from 20 or 30 years ago, to give some time for the impact to be assessed) from each one. Then try to show how those twenty publications have been socially beneficial enough to justify the expenditure to the public, when the same funds could have been used for many other things. I think anyone would find it hard to make a case that doesn’t sound fairly ridiculous, and it doesn’t help to say that one in a thousand of philosophers just might have a great idea that won’t be felt for a couple of centuries. The fact that many academics, alone, might not find a case like this ridiculous is not a good thing. Research is important, but attempts to justify the funding of so many professional philosophers on the basis of their research doesn’t look like a very good strategy.

The teaching work we do, or at least could do and ought to do, is really where we can make a strong argument. It’s easy for us to be blinded to this given our institutional reward structures, but the case that it’s useful for people to learn to think critically and self-critically, read and listen carefully, argue cogently, write precisely and clearly while learning to avoid major ethical and political errors and logical fallacies is much stronger than the case that the world won’t be able to function if a tiny fraction of the population can’t figure out a working account of epistemic modals or massage some difficulties out of the latest expressivist semantics. I’m not saying these projects aren’t worth pursuing. I’m saying that if we rest our case on the need for the public to support it to the extent it does, we’re going to lose this fight.

We need to get serious about not just improving our public image but about deserving the image we claim for ourselves. We tell the public that we aren’t mere custodians of ideas, and that we’re teaching our students to think for themselves. Great. We should make that message loudly and clearly to counteract the impression that laypeople have from looking through the ‘Philosophy’ sections in most bookstores or listening to poorly informed physicists in the mass media. But we also have to take a really good look at how we’re teaching what we’re teaching to make sure it’s even aimed at giving the students the skills we’re saying philosophy will give them, let alone that we’re successful at providing it. It’s really not all that clear that students sitting through lectures on great philosophers and showing that they know what the great philosophers said are getting any of those skills. There’s a big difference between learning the great reasoning of the great figures of the past and gaining the skills to produce your own reasoning, but many philosophy curricula do not reflect this. We can do better, and we’re going to need to if we want to stay afloat in the rapidly changing post-secondary climate.

I think Justin Kalef is basically right, but it’s worth thinking about why research is as incentivized as it is. Surely it is because academic institutions want prestige and this, for good or ill, comes from research. We should teach philosophy to improve our students’ cultural literacy, to improve their ability to think logically and carefully, and to encourage and enable students to think about questions that matter. This helps students and the world at large. (And if philosophers don’t do it then people who teach composition and history, for instance, will do it, and do it less well on average, instead.) We are also paid to do research, not so much for the benefit of humanity but in order to increase the monetary value of a degree from our particular institution. Is that something that taxpayers should fund? I don’t know. But so far as taxes from my state are used to benefit students mostly from my state it doesn’t seem completely unreasonable.

I feel the need to repeat my comment. *We don’t know that philosophy funding is revenue-negative; it might be revenue-neutral or revenue-positive.*

You can ASSUME it’s revenue-negative and then ask why taxpayers should have to bear this burden.

You can also ASSUME that most philosophy academics are pickpockets, and then ask why the people whose pockets are picked should have to bear this burden.

But I cannot see why anyone should have to answer any question that only arises out of an unmotivated and unjustified assumption.

Provide an empirically robust model that demonstrates the revenue effects of philosophy, then we can talk.

Alexander Douglass: I find your understanding of the dialectic here baffling. Surely showing that funding philosophy is revenue-neutral or revenue-positive would be part of a justification for spending public money to fund it. But the very fact that public money is being used to fund it is more than sufficient reason to ask for a public justification for such expenditures. So by all means, help to move this discussion forward by showing reason to think that it is revenue-neutral or revenue-positive.

I find that a weird way of talking. Unless it’s revenue-negative it’s not a net expenditure at all, so there *is nothing* for which to demand a ‘public justification’. If you ask me why I spent $60 and I reply that I only transferred it from one account to another, it would be ponderous to say: ‘Ah, so you justify the spending out of one account by pointing out that the same amount appeared in another.’ That is an excess of theory over fact; the fact is that I didn’t spend at all.

There is, of course, no way for me to determine the net revenue effects of philosophy funding, nor for anyone else to do so, as far as I know. So we just don’t know whether there is any net expenditure on philosophy. We don’t know if there’s anything to justify – maybe we should be proud of how much we are ‘saving’ the taxpayer. But the burden of showing that there *is* something to justify falls on those asking us to justify it. To repeat: it may be that most philosophers are pickpockets, but I feel no obligation to justify this behaviour until somebody provides evidence that we do in fact generally behave in such a way.

Most of this is beside the point anyway. I don’t think taxes finance government expenditure at all, at least not in the Anglo countries. Taxes serve the function of a reserve drain; they’re a way of controlling aggregate demand. Inflationary pressures from various channels determine the government’s need to tax. Revenue concerns have nothing to do with it, almost by definition, for a government that issues its own currency.

A few thoughts about this:

– From whence the demand to satisfy the taxpayer? To appease the salary-payer? Have these ways of doing things become so ingrained into our society and our thinking that we can no longer even raise the possibility of challenging them? Has the philosopher been reduced to a handmaiden for contemporary capitalism and its ideology?

– Aren’t these exactly the sorts of questions about the arrangement of society, about personal conduct, about value and valuing (etc.) that qualify as *philosophical* questions about politics and ethics and value, and which are thereby (if unwittingly) providing a rationale for philosophy in their asking?

– Shouldn’t we as philosophers be able to recognize these *as* philosophical questions, and treat them accordingly as part of what we do? If not, why not? This says more about the discipline, at least in its current state in the Anglo-American university system, than the problem of whether or not we can “appease the taxpayers” by “providing value”, where the latter is taken narrowly as acting in the service of contemporary capitalism and within its constellation of assumptions and distinctions.

– Philosophy’s ‘uselessness’ in light of Parsons’s questions (and setting aside whether this is genuine or merely perceived that way by the public) is at least in part a consequence of these very same values and expectations placed on the university system in order to produce ‘objective and measurable’ results. That expectation is already given to us and taken for granted; but why should it be?

I am not a philosopher, but here’s some weak empirical evidence for the “how to think” argument.

I’ve seen many such threads and articles before, featuring scientists, sociologists, historians, artists and musicians. But this one seems different – it doesn’t take for granted that the correct level of funding must be higher than the current one, or even that the current level itself can be justified. It lacks to a striking degree the usual circle-the-wagons mindset, where anyone who questions the value of funding what you do is presumptively a troglodyte.

So here’s the thought – philosophical discipline helps you consider even positions that your paycheck depends on your not understanding.

Then again there’s this.