Assessment & A History of Western Philosophy Test

Many departments have faced administrative pressure to develop ways to assess their teaching and their major programs by measuring the achievement of learning outcomes or objectives by their students.

One question is how to do this in a way that (a) is sufficiently quantitative but also (b) gets at, even if indirectly, what we are hoping students take away from studying philosophy, and (c) doesn’t take up an unreasonable amount of time.

In his search for such a means, Brendan O’Sullivan, chair of philosophy at Stonehill College, writes in with a question about one possibility—a test:

I teach at a small liberal arts/pre-professional college in New England in the philosophy department. There is more attention being paid to our having to assess our majors in terms of the goals/objectives we have. I gather this is due to NECHE, our regional accrediting agency.

I’m exploring options. One would be an objective-y test on the history of Western philosophy? Does anyone know of such a test? Has anyone developed one? I seem to remember having heard, way back in time, that there was a subject test for philosophy. Something akin to the subject tests that exist for English or Psychology. Has anyone else heard of that? Know whom I might reach out to to try to get a copy?

If you know about such a test, please tell us about it in the comments. Suggestions for alternate means of assessment that meet the desired criteria are welcome.

Related:

“Assessment and Philosophy Courses”

“Assessment, ‘Rich Knowledge’, and Philosophy“

I’m the assessment coordinator for philosophy in my department. Define your objectives and outcomes they track. But here’s my advice.

Make one assignment like a cumulative objective exam in logic or a meta-question end paper that involves a substantial end essay that must cite several readings and can hit all the outcomes you list the course to be achieving (Do not make your objectives and outcomes so numerous that one assignment can’t hit all of them. 3 or 4 tops). Alternatively it can be a take-home or blue book in class comprehensive essay. The point is to make one assignment that tracks all the course outcomes that you only need assess ONE assignment in software like Livetext or Watermark. If you must do formative and summarize assessment, then make your midterm as you would a cumulative final exam/ comprehensive essay and assess the midterm as you would the final.

if you have 5 or more program outcomes, don’t think that every course must assess each program outcome. Pick the best objectives and outcomes for the best classes or pick the most relevant ones you want to collect data on. It’s fine to assess logic differently than Intro.

You could also take drafts of an assignment and assess drafts of comprehensive essays and then assess the same writing assignment along with its prior draft versions in the same semester. In this model, you’ll need to meet with students and build in draft preparation and attending office consultations as part of their grade much like your English colleagues. I suggest using a rubric for philosophy essays and do not make draft consultations optional. Students won’t usually do extra work unless required.

And yes, this is in my estimation pointless to what we most want to do, but if done correctly, it can give you a picture of what your department is doing with what resources it has and burst narratives when pride should give way to data about how effective one’s teaching is.

Finally, you may be at an institution with bureaucrats that don’t think in terms of data saturation. I hope this isn’t true where you are. You need only assess as many courses to the point of data saturation. This seems the biggest challenge sometimes when some administrators demand all courses be assessed when a representative sample would still yield the same results.

J. Edward Hackett offers some good general advice above. Given that assessment requirements differ a bit from institution to institution, it might be worth asking the assessment regime there whether there are good models for assessment of program outcomes in adjacent disciplines at your institution. Sometimes colleagues in other departments have really good tools that are not too difficult to adapt. Meanwhile, one of the best philosophy-specific write-ups of assessment practices that I’ve read is: Wright, Charles W., and Abraham Lauer. “Measuring the Sublime: Assessing Student Learning in Philosophy.” Teaching Philosophy 35, no. 4 (December 2012): 383-409.

As for the idea of utilizing something like a comprehensive exam to measure student competency in any area of philosophical knowledge (history of philosophy or any other area), others below have commented on the GRE subject test in Philosophy, which was disbanded sometime in the last 25 years. My memory is hazy, but I believe that it still existed in the mid-90s when I applied to graduate programs in Philosophy, but by then I don’t think many (if any) programs required it anyway. I am certain that I did not take it. I’ve looked for this information in the obvious places one might look for it, but haven’t been able to find reliable information about when ETS discontinued it officially.

As for the question of the role such instruments might play in undergraduate outcome assessment, some of the other commenters below have suggested that it might be possible or desirable to develop a good test for knowledge of the history of philosophy. This might be true, but FWIW, I am skeptical of the value of any kind of nationally-validated instrument for several reasons, among them:

I took the GRE philosophy subject test when applying to graduate school back in 1975. It was a very good measure of one’s familiarity with the history of philosophy. The ETS might be willing to share old copies if they still have them on file.

I took that test in 1969 and did very very well. I did well because I skimmed WD Jones’ short history the days before the test and also knew what a Turing Machine was.

Honestly, you might be surprised what GPT 4o could do here; might be worth an hour looking at it. I just used it to write learning objectives for my AI & Ethics class and it did great. (I italicize anything my AI “TA” writes, to ensure attribution.)

not only can you get your objectives and outcomes from gpt, you can get your assessment rubric too. complete. nicely formatted and everything. now if somebody were to make an interface where i just upload the papers and the rubric ….

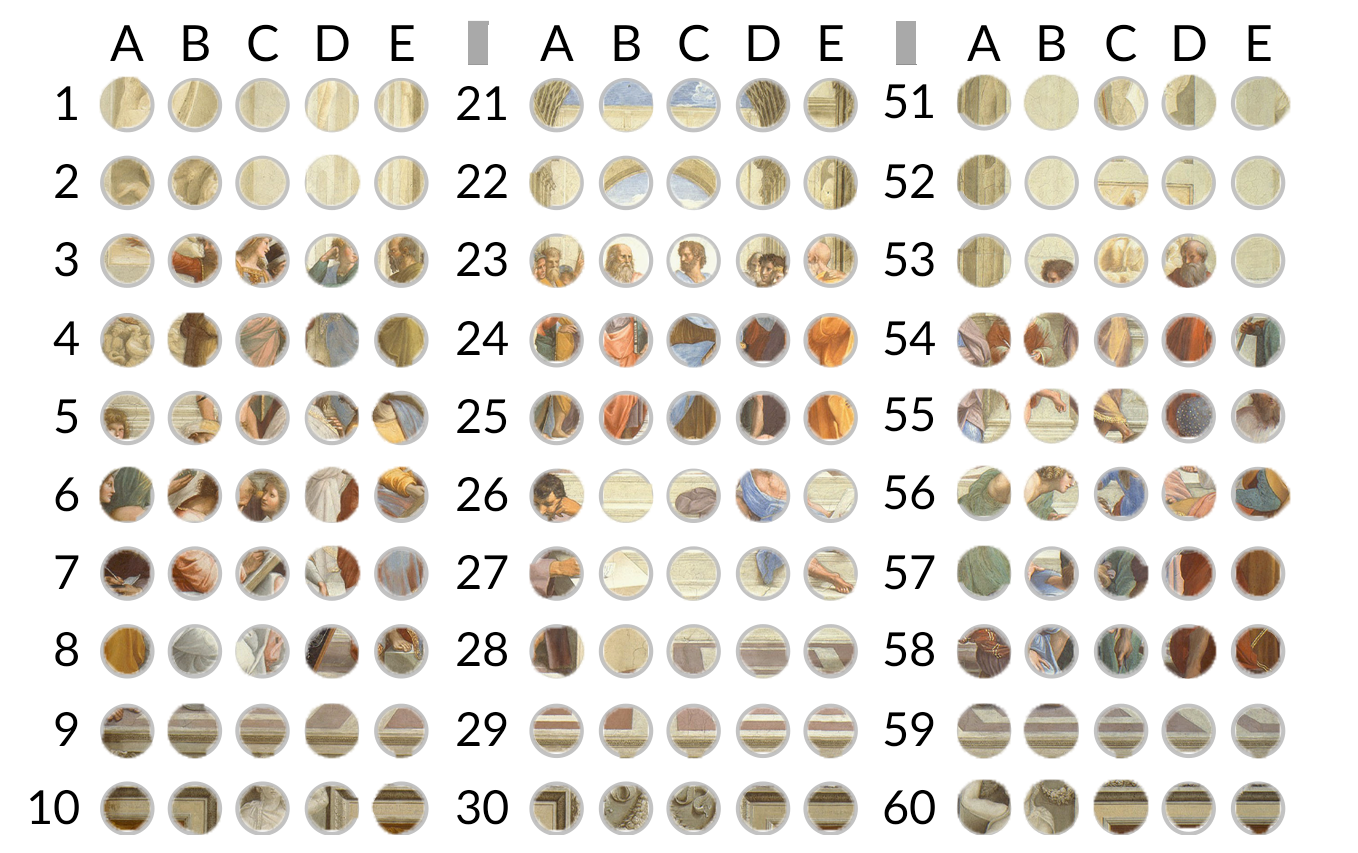

One of my two main measures of assessment when I teach the history of Western philosophy at CUHK-Shenzhen in China (mostly to students who take it to meet their general education requirements) are multiple-choice quizzes. As I set them up on Google Forms, those beauties are self-grading, and you get a number for each student. If you need inspiration, feel free to take a look:

1. Plato: https://forms.gle/3k7qFF4LLgZqRD8y6

2. Aristotle: https://forms.gle/wWqLo2TunFni1N3b8

3. Medieval Philosophy: https://forms.gle/VvyYiceaxGDAj3fk6

4. Descartes: https://forms.gle/KUru5YVajkWCNjdG6

5. Hume and Kant: https://forms.gle/w5oefgYKbYeCopYW8

(You will need to provide some fake information to get to actual questions…)

For the final, my students answer some questions in writing (of the “explain” and “evaluate” kind) – this requires actual grading, alas, but allows you to assess other skills we want our students to develop. I also assign points for each answer (for the explain-questions, there is usually a few things I want them to consider, if they consider all of those things they get full points; for the evaluate-questions, I award points not so much on the basis of content as on the basis of form: is the question answered directly? is there a justification? does the student anticipate objections?). Here’s a recent example: https://1drv.ms/b/s!As2Jh0vALYmqg5Y6qXvuGZ2bRAN7Jw?e=hDXbU3.

Maybe you could combine both kinds of tasks to address your needs? (It seems that the first assessment meets the desiderata a and c, but not so much b, whereas the second meets the desiderata a and b, but not so much c.)

I’m glad this question was raised, as there could be a huge benefit to developing nationally normed and validated assessment instruments for philosophy that extend far beyond their benefits for accreditation. These have been around in STEM disciplines for quite some time, allowing their discipline-based education research to thrive.

As the director of a teaching center, I am deeply committed to sharing the latest *research* on pedagogical practices in higher education, but I think philosophers can ask a reasonable question about whether research in STEM transfers to the philosophy classroom. There are a number of reasons there isn’t as much empirical research on teaching philosophy (including our methodological training), but one of them is that we just don’t have widely accepted and easy to use measures of what we want our students to learn.* It’s hard to test whether various strategies “work” when we don’t have a quick way to compare results across different interventions.

The development of concept inventories in STEM has been an ongoing process where folks across the discipline work together to develop, test, critique, and revise them again and again and again. And they’ve proved invaluable for research on teaching in these disciplines, which has, in turn, led to dramatic changes in pedagogy for the better. I’m confident philosophers could do the same thing, we just need 1) help from our colleagues who understand instrument design; and 2) the kind of funding that NSF provides those doing education research. I’d love to see philosophers working together with psychologists to get funding for this if they haven’t already! There is no question they won’t be perfect, but even imperfect measures can be helpful in moving us beyond the status quo, where we are mostly making decisions based on intuition.

*There are actually some validated measures that already exist that might be useful, but they have usually been developed by psychologists interested in studying moral development or reasoning skills for other purposes. I’d love to see the discipline engage with those instruments and tweak them for the purposes of studying what we can do in the higher ed classroom!

Realized it would be helpful to share more information on concept inventories in STEM for those interested. This has a nice summary (as well as some interesting proposals to take them further): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23752696.2018.1433546%40rhep20.2018.3.issue-V1?scroll=top&needAccess=true

Thanks to everyone who weighed in. I’ll ruminate and talk with my colleagues. If we come up with anything I think would be useful, I am happy to pass it along. Yours, Brendan