Philosophical Readings Related to the Eclipse

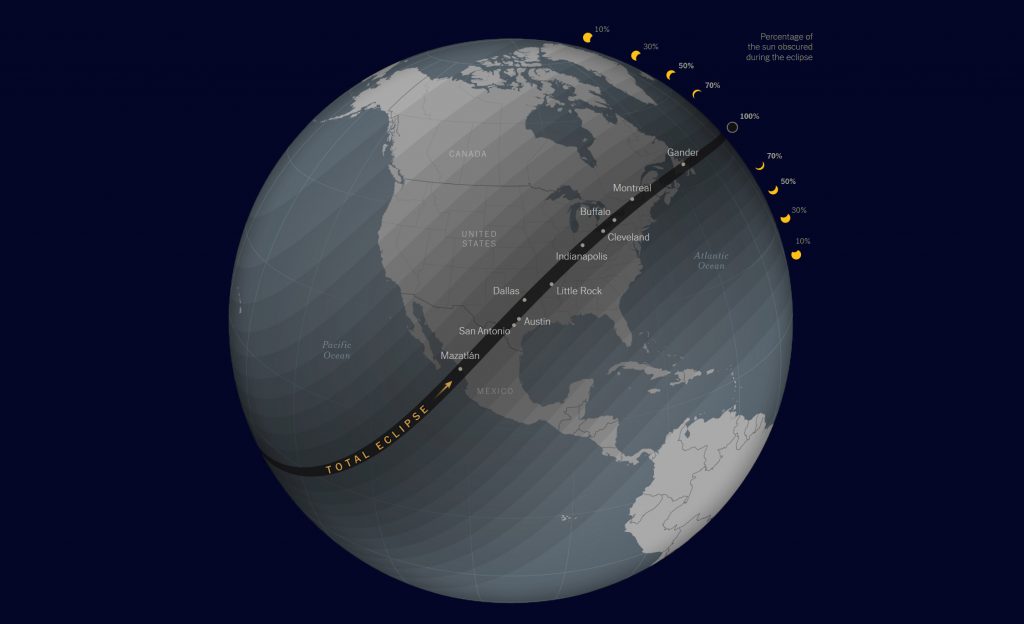

A total solar eclipse will be taking place on April 8th.

[via NYT]

Laura Papish, a philosopher at George Washington University, is hoping Daily Nous readers may have some positive answers to that question.

She writes:

I’m wondering if you might consider soliciting from folks suggested readings to link up with the upcoming solar eclipse. My students will be viewing it, some within totality zones, and we will have a discussion later that day about their experiences. I’m interested in any readings that might supplement or enhance their viewing experience, and I was thinking that other instructors might be similarly interested in some crowd-sourced reading suggestions.

I would think that there is work in the history and philosophy of science on eclipses, yet perhaps there are philosophical or philosophy-related writings on the emotions, the environment, epistemology, ethics, meaning, metaphor, perception, time, and other topics that have some relevance to eclipses. Maybe there’s some philosophically-suggestive fiction related to eclipses?

Your suggestions welcome.

Not purely philosophical, but might be an interesting read: https://academic.oup.com/ej/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/ej/uead117/7502802?redirectedFrom=fulltext

In the Analects of Confucius (19.21), Zigong remarks [Slingerland’s translation], “A gentleman’s errors are like the eclipse of the sun or the moon: when he errs, everyone notices it, but when he makes amends, everyone looks up to him.” Just a short thing, but full of lots to unpack philosophically! And Slingerland’s Hackett edition supplements this passage with some of the historical commentaries that further explore the eclipse metaphor.

Roy Sorenson, Seeing Dark Things

He has some other fun work that could be relevant (e.g., “We See in the Dark”).

Not about eclipses, specifically, but a great piece by Helen De Cruz about being in “awe” of scientific phenomena:

https://aeon.co/essays/how-awe-drives-scientists-to-make-a-leap-into-the-unknown

Must read Sorensen! See

Sorensen, Roy (1999). Seeing Intersecting Eclipses. Journal of Philosophy 96 (1):25.

Some of this is also treated in his Seeing Dark Things book that another commenter mentioned.

The central puzzle concerns what you see if there are two moons between you and the sun during a perfect total eclipse. You don’t see the closest moon on the assumption that it’s causally inert here and you can only see what you’re optically affected by. You don’t see either the far moon or the sun on the assumption that both are perfectly occluded by the opaque near moon and you can’t see through opaque objects.

You can generate pretty much the same puzzle with just one moon, and raise the question of which side of the moon you see during an eclipse– the causally inert near side or the occluded far side?

I won’t spoil Sorensen’s solution to the puzzle, but it’s clever and amusing (as is typical for Sorensen).

Dietrich von Hildebrand’s Aesthetics, Volume I, Chapter 14, is about how nature is a bearer of beauty. Lots to chew on for an extended discussion on what the eclipse presents. I would be happy to provide the full chapter (I can forward to you, Justin, or to the professor looking for readings).

Gernot Böhme also wrote an interesting piece on the phenomenology of light.

Lastly, Annie Dillard’s “Total Eclipse” is indispensible.

I’m not sure about having students read them, but I’d maybe discuss the importance of Bayle’s “Various Thoughts on the Occasion of a Comet.” (Yes, I know comets are not eclipses, but the idea of whether unusual celestial events have a special meaning is still there). I’d also discuss how we know scientific theories are true, specifically the role of empirical confirmation of Einstein’s theories in the 1919 solar eclipse.

Phaedo, 99d-e, of course:

Socrates proceeded: “I thought that as I had failed in the contemplation of true existence, I ought to be careful that I did not lose the eye of my soul; as people may injure their bodily eye by observing and gazing on the sun during an eclipse, unless they take the precaution of only looking at the image reflected in the water, or in some similar medium. That occurred to me, and I was afraid that my soul might be blinded altogether if I looked at things with my eyes or tried by the help of the senses to apprehend them. And I thought that I had better have recourse to ideas, and seek in them the truth of existence.”

In “Putting explanation back in ‘inference to the best explanation'”, Marc Lange mentions this delightful fact about solar eclipses to illustrate a general point about the relationship between explanatory goodness and truth of a hypothesis. Here’s the text, from p.4:

“IBE permits explanatory considerations to be overridden by other considerations so that the “best explanation” of one fact need not be the most plausible hypothesis all things considered. Even while recognizing the support bestowed on a given hypothesis by its capacity (if true) to give a good explanation of some fact, we may justly regard a competing hypothesis that would not “best explain” that fact as nevertheless better supported by the entire body of available evidence.

For instance, although the Sun’s diameter is about 400 times greater than the Moon’s, it is on average about 400 times farther away, so – remarkably – they have nearly equal angular diameters in Earth’s sky. (Hence the Moon is just the right apparent size to cover the Sun’s disk without covering the Sun’s corona, producing spectacular solar eclipses.) The equality of their angular diameters would be better explained by some theory ascribing their diameters and distances to

some common cause than by the theory that this equality is coincidental. Yet all things considered, the coincidence theory is better confirmed (Naeye, 2000:94).”

Yes, I love this one for a critical thinking / phil-science / epistemology course. It can pair wel with discussing conspiracy theories. Things that on their face call out for explanation — and yet sometimes coincidence is the better answer.

This is bound to be a controversial suggestion, but the Intelligent Design proponents Guillermo Gonzalez (astronomer) and Jay Richards (philosopher) use the phenomenon of solar eclipses as part of a kind of teleological or “fine-tuning” argument for the existence of God; they see great significance in the fact that perfect solar eclipses are possible only in the one place in the solar system that has observers, namely earth. This example is part of their larger argument concerning what they see as a meaningful congruence of the conditions for habitability, and the conditions for scientific discovery (they develop this argument in their 2004 book The Privileged Planet: How Our Place in the Cosmos is Designed for Discovery.) The association of these authors with the Discovery Institute and the ID movement might lead some to dismiss the argument out of hand, but it is nonetheless an interesting argument, fleshed out with a good deal of detail. I’ve found it a good foil to use in philosophy of science class in trying to explain the anthropic principle, and how (as Dawkins urges) it offers an alternative to “design” arguments such as this one.

I second the suggestion of Helen De Cruz on wonder and awe!

In addition, a total solar eclipse can only happen during a new Moon, the phase in which the Earth-facing side of the Moon remains in the shadows. This can be connected to Karl Popper’s speculation about the Presocratics: Parmenides has been credited with the discovery of the nature of the phases of the Moon, which is a necessary step towards a natural explanation of eclipses. Perhaps Parmenides was so shocked by discovering that the Moon is an unchanging sphere that merely appears to wax and wane due to deceptive shadows (just like the Sun merely appears to change during the eclipse) that he came to the conclusion that all apparent changes are illusory.

Popper, K.R., 1992. “How the Moon might throw some of her Light upon the Two Ways of Parmenides,” Classical Quarterly, 42: 12–19.

Wow, I had no idea that it might not have been until recorded history when people noticed that the phases of the moon perfectly track the angle to the sun! It’s such an obvious fact once it’s pointed out, and I thought that even before recorded history, people were tracking which part of the stars each of the celestial bodies were in, so it should have been obvious that the new moon always occurred when the moon and the sun are in the same house, and full moon always occurred when they were in opposition.

I am a little surprised no one has as yet mentioned Steinman and Tyler’s (1983) rather profound investigation of the “total eclipse” trope, especially as it arises within the context of intimate interpersonal relationships. This succinct (indeed pithy) work very deftly prompts us to inquire as to the precise commencement of forever (tonight? yesterday? or some as-yet-unspecified moment?) and whether it is indeed possible for an entity that is falling apart (physically? ontologically?) to simultaneously fall in love, more specifically in love that endures only “in the dark.” No doubt this remarkable disquisition fails to conform to the Procrustean parameters of professionalized “analytic philosophy,” but to persuade the sceptics, there’s really nothing I can say …

It’s not philosophy, as such, but the final track of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon is evocative, playing on the symbolism of the sun as the (Platonic?) light of reason and the moon as the bringer of madness.

“Everything under the sun is in tune/but the sun is eclipsed by the moon.”

This is about lunar eclipses, but still worth knowing. The Philosopher writes: “An earthquake sometimes coincides with an eclipse of the moon […] When the earth is on the point of being interposed, but the light and heat of the sun has not quite vanished from the air but is dying away, the wind which causes the earthquake before the eclipse, turns off into the earth, and calm ensues. For there often are winds before eclipses: at nightfall if the eclipse is at midnight, and at midnight if the eclipse is at dawn. They are caused by the lessening of the warmth from the moon when its path approaches the point at which the eclipse is going to take place. So the influence which restrained and quieted the air weakens and the air moves again and a wind rises, and does so later, the later the eclipse” (Meteorology II.8, 367b20-367b31)

The history of the 1919 eclipse expeditions to confirm General Relativity is interesting, and there are some good philosophy of science angles you can take on that case (confirmation, theory testing, margins of error and inference, expert testimony, bias, paradigm shifts, understanding spacetime as curved, and a lot more). Here are couple of citations you might consider:

Almassi, B. (2009). Trust in expert testimony: Eddington’s 1919 eclipse expedition and the British response to general relativity. Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics, 40(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsb.2008.08.003

Earman, J., & Glymour, C. (1980). Relativity and Eclipses: The British Eclipse Expeditions of 1919 and Their Predecessors. Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences, 11(1), 49–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/27757471

Astrophysicists today regularly use this “gravitational lensing” effect first observed during the 1919 eclipse to study things like dark matter in galaxies and clusters of galaxies. It is interesting to realize that a careful observation of a solar eclipse showed us that mass really does bend space in the way that Einstein predicted, and that we were then able to use that fact to study objects that are millions of lightyears away.

Three topics I can think of in philosophy that are of direct relevant:

Eclipses (and other astronomical phenomena) are often used as good examples of cases where we can have knowledge of the future, which cause problems for simplistic theories that are fully skeptical about all future knowledge. (They also cause problems for simplistic causal theories of knowledge, and probably others.) I don’t know of any philosophical work that dwells on the example though – it’s usually a quick offhand remark.

Others have already mentioned Roy Sorensen’s work on eclipses in a hypothetical double-eclipse, and on seeing dark things. I don’t know if there is other work on it.

The literature on vagueness often talks about “penumbral connections”, but I think most philosophers working in the area don’t think much about what that metaphor means. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umbra,_penumbra_and_antumbra)

When a light source is larger than a point (as the sun is), a physical object that is large enough has some region where it blocks all light from the source (the “umbra”), and some region where it blocks only some light (the “penumbra”). When the moon gets in the way of the sun, the region in the penumbra is said to have a partial eclipse, while the region in the umbra is said to have a total eclipse.

I think the metaphor is that when you have a total eclipse, you are definitely having an eclipse, and on a normal day you are definitely not having an eclipse. But when you have a partial eclipse, it is vague whether or not you are having an eclipse, but it’s true to say that if you’re having the eclipse then so is anyone else who is closer to the umbra.

That said, in practice, there’s nothing vague about it. A partial solar eclipse is really neat, especially if it’s something like 99% of totality. But a total solar eclipse is a completely different experience.

I think a total solar eclipse is also a useful experience of the theory-ladenness of observation. When I saw the 2017 total eclipse, one of the most amazing aspects of it was seeing the Moon as a three-dimensional object suspended between me and the sun. I’ve known for as long as I can remember that the solar system is three dimensional, and the moon is a rough ball between the Earth and the Sun, but really *seeing* it was quite a different experience. And at the same time, I knew that many people in the past had seen this same sight and *not* realized that this was a working of a three-dimensional mechanism of sorts, so somehow my perception, which gave me new appreciation for the theory I already knew, was essentially connected to my prior knowledge of the theory.