Phriscos

A “Frisco,” I recently learned, is “something that outsiders spontaneously say that secretly marks them as outsiders unbeknownst to them.”

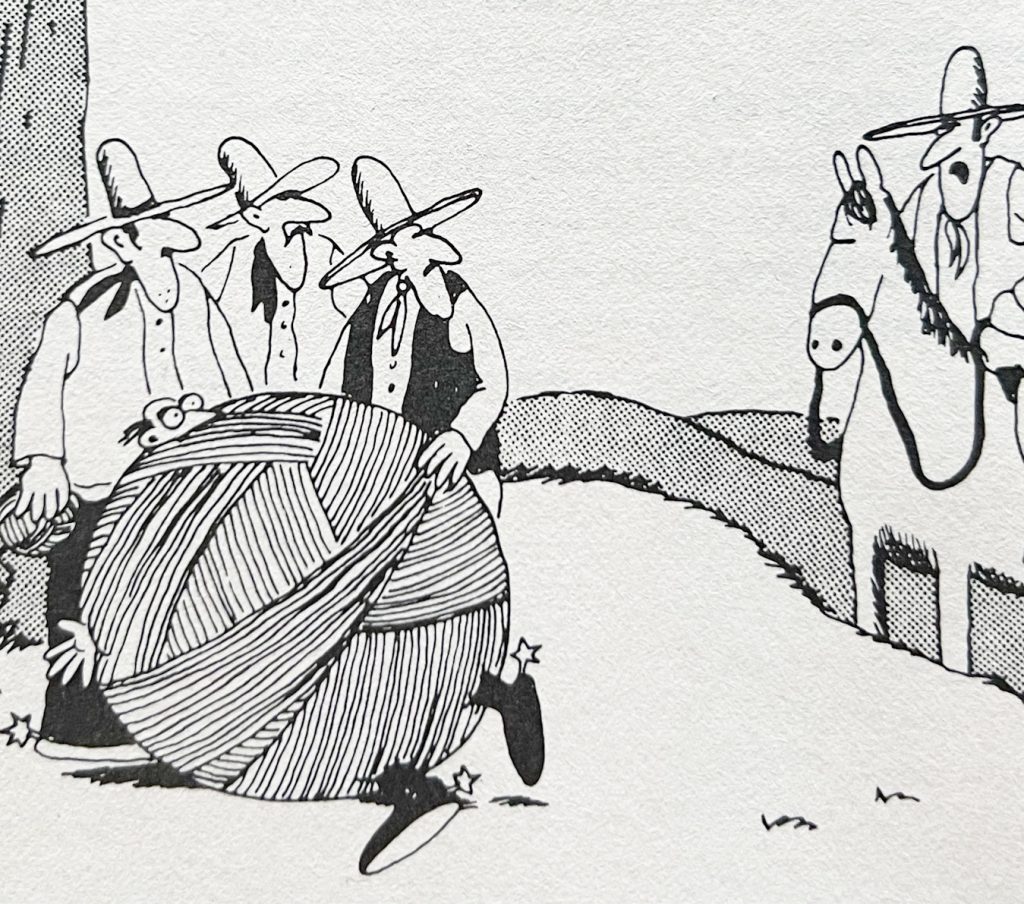

[from a “The Far Side” comic by Gary Larson]

Several years ago we had a discussion of what we called “shibboleth names” in philosophy, that is, names the common mispronunciation of which marks speakers as inferior in some way. Maybe we should have called them “Frisco names.”

In any event, the domain of philosophical friscos—let’s just go all in and call them phriscos—goes beyond names and mispronunciations.

A classic example of a phrisco, offered by Scott Hill (Innsbruck) in response to Sauer, is using “begs the question” among philosophers to mean “raises the question” rather than “assumes the very thing it sets out to prove.” (Yes I know some of you think we should give up on this one, but nonetheless it still functions as phrisco.)

Here’s another phrisco: using “refuted” when one means “disagreed with”.

I think we could have a little fun, and at the same time provide a valuable service to philosophical novices, by identifying these phriscos.

I’ve never actually heard anyone use ‘Frisco’, only ever heard people complaining about its supposed use.

But more seriously, variations on “this is a convincing theory but it’s all a matter of perspective in today’s society”. Or “that’s an opinion, not a fact”.

Though you may be right about ‘Frisco’, ‘Cali’ is another story. I never heard this (other than from LL Cool J) until I moved out of the state. Makes me cringe when I hear it.

2nd person plural pronouns tell one’s linguistic story.

British people very often say “San Fran”.

Oh, I still hear “Frisco” from visitors. Every time a tourist utters the word, a vegan burrito dies.

I also hear “San Fran”, but that’s less offensive. “SF” and “The City” are the preferred terms, though I never liked “The City” because it seems presumptuous for any city to claim that name.

As for “Cali”, I say that and have lived here most of my life! On its history: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-06-01/love-it-or-hate-it-the-nickname-cali-has-a-surprisingly-long-history

People say “The City” outside nearly every big city. New York, Boston, Chicago… Do you work in the city? Let’s go into the city. Heard all the time.

True, but I’ve only seen it capitalized when it refers to SF. Do other cities use it as a proper noun in referring to themselves?

The usage I’ve heard in the Bay area about SF is basically isomorphic to the usage I hear in NYC. For some reason though, people in SF often seem to think that their use of “The City” is unique to SF, since your comment is not at all the first time I’ve heard this.

See China Miéville’s subtle caution against confusing The City with The City.

Right, I get that many or maybe every city might be called “the city” by locals. But is there a city, besides SF, where it’s habitually capitalized as “The City” when written?

I’ve lived in/near many major cities from coast to coast in the US, and I don’t recall seeing that in print for other cities. On a quick online search of which cities are called “The City”, I didn’t find anything authoritative, but here’s one explanation of the origin of the proper noun:

https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-origin-of-the-name-The-City

The City of London (i.e., the small part of modern London that was +/- the original Roman settlement) is referred to as “the City.” To say you work in “the City” usually conveys that you work in finance or some related field, given the banks etc. located there. In contrast, to say you work in “the city” would be compatible with working in a Starbucks in Fulham.

Actually outside of Boston it’s usually “town,” as it used in “We went into town to see a movie .”

Now that you mention it, Los Angeles is also a “town” to many locals, even though it has nearly 4 million people in it. It’s just spread out and doesn’t feel like a city, except for downtown and maybe Century City.

Here’s a map of the states with a smaller population than LA:

Using “infers” to mean (informally) “implies”

Yes!

When I hear someone mix up “infer” and “imply” I wonder how someone can even think without knowing the difference between inferring and implying.

I would think that mixing up “to infer” and “to imply” marks one as someone who has made a mistake in the use of English (ditto for “begs the question” and “raises the question,” although that is a mistake made so often now that it may be on the verge of becoming accepted usage).

Perhaps a phrisco should be something that marks one as an outsider specifically to philosophers, rather than just something, such as mixing up “infer” and “imply,” that marks someone as either unfamiliar with or deliberately ignoring the ordinary dictionary definition of these words. Afaik (please correct me if I’m wrong), there is no difference between the way in which philosophers use “infer” and “imply” and the way in which speakers of correct English who are not philosophers use “infer” and “imply.” So it’s a fairly weak phrisco, if it’s one at all, since it’s not a philosophy-specific thing.

The uses of the words “valid” and “logical” in statements such as “That’s a valid point” and “That’s not a logical answer.”

The use of the word “moral” in statements such as “She wasn’t being moral.” (This one might be an edge case. I think philosophers tend to use the word to characterize a domain of philosophical investigation, but I wouldn’t be surprised to learn I’m wrong.)

The use of the word “philosophy” in statements such as “My philosophy is [. . .].” (I’m pretty sure professional philosophers nowadays wouldn’t be caught dead saying something like this.)

To be clear, I actually don’t think the uses I’ve indicated are inherently wrong or inappropriate. But I do think they mark one as not being a professional philosopher.

I agree with your point about “valid” and “logical”.

I also agree that most philosophers probably wouldn’t use phrases like “my philosophy is …” (No professional philosopher has ever said such a thing to me so far as I can remember. These days I only every hear administrators talk about “philosophies” and they seem to have adopted this use from the business world in the same way that administrators irritatingly use “ask” as a noun).

However, I have doubts about the term “philosophies” as a phrisco. The Stoics, Academics, and Epicureans refer to one another as different “philosophies” back when this team implied a particular world-view or way of life. In a discussion with scholars of Hellenistic philosophy, using the term “philosophies” wouldn’t be a phrisco. I suspect that it is a modern prejudice for contemporary philosophers to avoid using “philosophies” in this way.

Good point!

I think you’re generally right about the valenced use of “moral.” Another edge case related to moral is that I find many students taking their first introductory ethics course are arriving with some distinction between moral and ethical that I’m quite unfamiliar with! I know that some philosophers have distinguished between the two, but I generally use “ethics” and “moral philosophy” interchangeably. My students seem to think that morality refers to one’s personal code of conduct whereas ethics refers to societal/cultural norms.

Tim Scanlon once pointed out that when a politician has an ethics problem, it’s money. But when a politician has a morality problem, it’s sex.

Nothing wrong with “she wasn’t being moral.” True, there’s another use of “moral” to denote the subject matter — the part of ethics that deals with what we owe to others, roughly, where “ethics” refers to the larger subject of how we should live, generally (including how much weight to give moral considerations over others). But “moral” is also a perfectly acceptable way of denoting that which is in accord with the dictates of the right, true morality, or of “morality” as it’s sometimes called.

I’m the 18th and early 19th century, ‘moral’ was often used to mean ‘non-physical’.

I see a lot of the moral/ethical distinction among my students, too (and also online). I’ve often wondered where it came from.

Ugh. In*

In the milieu where I grew up, “morality” was almost completely about one’s sexual behavior. But, I think that use must be a lot older because Russell, somewhere I don’t remember off the top of my head, makes a comment about how for the “common man” morality is mostly about sexual activity.

In the wonderful film _Election_, there’s a bit in the start where the teacher played by Matthew Broderick is trying to get his students to make a distinction between morality and ethics. (I think maybe he teaches civics or something like that) and only Tracy Flick (Resse Witherspoon) can give it, but she’s just repeating back a rote formula. (I’d hoped to find the relevant clip to link to, but could not.) That seems to suggest that making this distinction was common, perhaps especially in education schools, by the later 1990s, if not befor, and that kids are maybe learning it from their high school teachers. (I remember thinking the distinction sounded simplistic to me when I watched the film, though I don’t recall now how exactly the distinction was made.)

Asking: “Who is your favorite philosopher?”

I have never been asked this by a philosopher. I am often asked this by non-philosophers.

This question is such a tough question even ordinarily. But it really has a sting in couples therapy for a mixed-discipline couple.

I rarely laugh out loud when I am alone sitting at my computer. But this comment made do it.

Perhaps using the word ‘aesthetic’ as an adjective (“it’s so aesthetic”) or as a synonym with style.

Ooo good one!

it takes everything in me not to say something pedantic when I hear this

I wonder if existentialism scholars balk at uses of “bad faith” in statements such as “They were bargaining in bad faith,” and if philosophers of science do the same at uses of “paradigm” in statements such as “Moving forward, the corporation will be operating under a new paradigm.”

I will vouch for the latter.

The legal term “bad faith” (basically what’s suggested above) significantly pre-dates the translation of “mauvaise foi” from French, so it would be odd to balk at it, though I guess some may do so.

I see your point, and I think you’re right.

Confusion between (epistemic) uncertainty and (metaphysical) indeterminacy.

My first introduction to a philosopher was in a general education Humanities course as a freshman. My teaching assistant for that course was a philosopher. One day, in discussion, I commented that the multiple origin stories in Genesis ‘contradict’ one another, to which the TA replied: “Do they contradict, or are they just different?” — That one left me quiet and confused for some time.

Since at least two of the stories relate different “days” of creation for humans, they at least are logically contrary in propositional content. That’s more than just “different”, and shows the TA did not provide the most accurate response.

Well, he was just a graduate student after all. Merely a padawan on his way toward full pedant status.

Using the term ‘possible world’ to mean an alternative outcome of a choice (like in a common (mis)understanding of the Many-Worlds Interpretation) or an alternative dimension we could travel to (like in Rick and Morty and comic book multiverses), rather than to mean a formal device for modal logic or a truthmaker of a modal statement.

With respect to the common use of “begs the question”… I say never give up, never surrender!

Which begs the question whether one should just give up at a certain point.

Appears the “No Frisco” campaign has been successful, for the most part. Why has question begging been so hard to eradicate? Seems to be something of a damp squid, or an ad homonym.

Using the term “argument” to describe a disagreement.

I would say worse, using “argument” to mean something like “thesis”–not ordinary English as far as I know, but surprisingly common in humanities disciplines. Also when I was studying German in Germany (in German), the teacher explained to us the distinction between “Argument” (meaning “thesis”) and “Argumentation” (meaning “argument”) as if this were a matter of basic German vocabulary, and as if we had to be particularly thick not to get it. In fact, at least in my experience, German philosophers use “Argument” the same way English-speaking philosophers use “argument.”

Also, while we’re at it, the use of “intentionality” in contexts like “setting aside the question of intentionality” = “setting aside the question of whether the author is doing this consciously and deliberately.” And when philosophers talk about something being “predicated of” something else, and the people you’re talking with think that’s equivalent to “predicated on,” which they use to mean “presupposing” or “conditioned on.”

I have been asked “What’s your philosophy?” before. That would seem to count.

Pronouncing George Berkeley and Berkeley, California, the same way

UK pronunciations are to blame for that one. Like Magdalen College, whose pronunciation bears only a tenuous resemblance to some of its letters. Or, worse, ‘Beaulieu’.

And that’s even despite the fact that the place in California (and so, derivatively, the university) is even named after the Bishop George!

One of my undergraduate professors drilled the difference into our heads with this: ‘Berkeley, good school, Berkeley, bad philosopher.’

In all honesty, I do not think she thought Berkeley was that bad of a philosopher, but it was an effective way to help us remember the difference!

I took a graduate class on Berkeley with a winner of the Turbayne Essay prize who would bring his three dogs into the seminar room – there was Lockie, Barkley, and I do not remember the name of the third. It was definitely not Humey, though.

“Deconstruct” to mean “criticize” or “argue against” when it more strictly means something like “assemble a loosely connected set of words and images in the shape of a paper airplane and launch it towards a target, with a sultry glance towards a camera and/or audience.”

Ouch! I hear this a lot on (French) TV, it is a really good one.

Hmmm…not so fast, aspirant linguistic hegemons:

https://www.sfgate.com/local/article/rappers-poets-activists-say-frisco-17441731.php

Praise of certain people as great philosophers can operate like phriscos, e.g. Jordan Peterson or Ayn Rand.

Nice!

I really enjoy the concept of a frisco/phrisco, but having come across the original article in the past, this line “No, correlation does not imply causation, but it sure as hell provides a hint” always makes me tear my hair out. Correlation sure as hell does not provide a hint, unless you already have a pile of other context. A negative correlation could easily mask a positive causation, or vice versa, or it could have no causal implication at all. In fact, treating correlation like a weaker cousin of causation is a frisco of sorts for me.

Yeah, but here’s a correlation I keep coming across, and it seems to challenge what you’re saying: (a) cause, (b) effect. They always seem to go together, and the fact that they do is definitely a sign (hint?) of something deeper going on between them, I suspect…

Indeed, but if (a) was “ice cream consumption” and (b) was “murders” what is the “something deeper” you’d suspect there?

Does it not provide a hint though? Seems to me that absent other evidence, the fact that A is correlated with B raises the probability that there’s a causal relationship between the two. Of course that might be overridden/undermined by other evidence.

Not really? Or at least not without additional context. As a practical example, suppose I’d like to know if sunspots cause judges to give out harsher sentences – I find a positive correlation – now what? Sure I’ve found that A and B go together, but I’m just as unsure of the underlying causation as before. Is it a positive causal effect ? Or is it a negative causal effect but some other correlated factor (like weather) drives the positive correlation? Or is it completely irrelevant and the found correlation is driven by other factors entirely? I guess I just don’t see how learning there’s a positive correlations would update my thinking. (To be clear, I’m using terms here in a very social science/observational data, statistical sense, which I believe is the context of the article – experimental data is a different story).

You could appeal to Occam’s Razor, no?

sorry to pop back in, but I was just thinking about this some more. if it’s not the case that observing a correlation should ceteris paribus raise my credences that there’s a causal relationship, then how could we *ever* infer causal relationships from observations of correlation?

Great question! In fact, that’s basically THE fundamental question of lots of modern applied statistical analysis (again, in the context of the original Slate article of social science-y observational data). In short, it comes down to “additional context”. On its own, correlation is just a mathematical statement about covariance, and so finding that cov(X,Y) > 0 is just a bit of descriptive evidence that we observe two things together more often than not. Causation is much harder, and is more of a statement about the underlying data generation process and understanding why X varies and why Y varies, and whether or not you can attribute variation in Y to variation in X. Correlation is not just a weaker version of causation like some sort of difference in degree, rather it’s a difference in kind.

So back to the original article, telling me that Cov(sadness, emails) > 0 because you surveyed some college students and calculated some value using two columns of your data just really doesn’t change my causal beliefs at all about whether sad people email, or email makes people sad, or neither of the above.*** But adding context might turn that correlation into something that can be interpreted causally (for example, if researchers randomly assigned the number of emails one could send, or there was some technical event that made more or less easy to send by happenstance, or there was some other well-established body of empirical literature to draw on to make an Occam’s razor style argument, or the researchers were able to statistically control/condition for all the possible confounding and selection variables somehow, etc etc). Again, this is what lots of modern applied statistical analysis is trying to do in much of the quantitative social sciences when establishing if/when a correlation might have a casual interpretation.

But setting aside whether that’s the right or wrong way to think about causality and correlations, some of the responses here in fact confirm that the Slate article on “frisco” does in fact contain a “frisco” – drawing a causal relationship from a raw correlation would instantly and in a not-obvious way mark you as an “outsider” in many quantitative social science settings. But per the links, apparently in other settings “Scientists know that, whenever someone says “correlation does not imply causation,” we are dealing with clueless civilians.” Thanks for following up – Cheers!

*** While I do prefer causal inference to casual inference, I don’t think I’m using “hint” to mean “conclusive proof” as cheeky suggests. I mean “hint” in the sense of – “does this change my beliefs about a causal relationship?” and I still say no, it does not. Part of that is just hard-won experience working with large datasets and putting in the work to drill down to causal relationships between variables. In general, there really is no pattern between what the raw correlations initially suggest and what the causal effect is. The sign, magnitude, and significance of the causal effect are often so different from the initial correlations that I don’t see any reason to think a raw correlation means anything other than cov(x,y)/sigma_xsigma_y != 0. With large datasets nowadays EVERYTHING is correlated (significantly) with every other variable, and given that everything can’t cause everything, it’s not clear why any particular raw correlation, absent the aforementioned context, should provide any sort of causal hints. Lots of bad policy has been made on the basis of interpreting correlations as hinting at causation (hello race science), so I think it’s healthy to maintain a thoughtful and appropriate skeptical firewall between them.

Yes, a lot is being smuggled into the conversation via the word hint. How about this phrasing?

I agree: Correlation definitely provides a hint — about what you should investigate. It does not provide a hint about what you should believe. For that, you need to learn more.

That’s really the problem with beliefs: once you acquire one, it’s too easy to forget how you acquired it. Too many people are running around with false beliefs based merely on hints.

You seem to be using “hint” the way a lot of people would want to use “(conclusive) proof.”

“Premise” as a synonym for part of what someone said or argued (whether it was their premise or not).

“Metaphysical” for supernatural.

“A priori” for “without checking.

Saying or implying that philosophy and spirituality are related.

Saying or implying that, e.g. Beaudrillard or Latour are doing the same kind of thing as, say, Rawls or Kripke.

To be fair, “metaphysical” has been used plenty of times throughout philosophical history as a pejorative like “spooky.”

This is a lovely opportunity to delight in all the ways the rubes get our technical terminology wrong, though in many of the examples adduced so far (“bad faith”, “a priori”), the technical term is in fact borrowed from a pre-existing common term, so it seems a bit presumptuous for philosophers then to turn around and say that the commoners are getting it wrong. But as for “Frisco”: growing up in Sacramento, we always referred to the city in question as “the City” or as “SF”, though there was a lot of very fine-grained local variation in ways of speaking (e.g., only kids from Oakland were allowed to say “hella”) and it wouldn’t surprise me if the Central Valley had different shibboleths than the Bay Area. That said, “Frisco” never sounded particularly wrong to me, I think in part because the term occurs in the lyrics to Otis Redding’s “Sittin’ on the Dock of the Bay” (1967), and that’s a song that San Franciscans generally interpret as an homage to their city. “Cali” by contrast makes my head explode. Whenever I hear it, especially from British people who have just found out where I’m from, I have a strong desire to cut off relations immediately.

I would very much like it if more philosophers used Stax artists instead of intuitions to justify conclusions. I mean as evidence that couldn’t be less reliable than the random reactions of some doughy Englishman at Oxford/Cambridge and at least it might get some poor dorky philosopher to listen to Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, Carla Thomas, William Bell, Booker T and the Mgs, or the Staples Family.

The last thing raises a good point: it seems more offensive for non-Californians to say “Cali” but less so or not at all for in-staters. It’s like slurs of any kind: ok for the in-group to say it, but not as much for out-groups.

Not sure, but has any academic philosopher ever used the word “philosophize” in a non-ironic way?

Example: “Hey, where did Mary go?” “Back to her office to philosophize.”

In all honesty a lot of these sound more than a little dick-ish. Some are just jargon that we use in one arbitrary way. I mean mathematicians might as well make fun of folks for not using “argument” in the sense of the values that go into a function or “induction” to mean generalizations resting on experience rather than proofs by mathematical induction. A lot of others are just pronouncing foreign names in the wrong way (I did this when I started philosophy with Camus of all people). I do absolutely hate that “beg the question” has evolved to just mean “raise the question” since it means a specific thing that is hard to express otherwise, but what can you do? Of all the annoying pedants, the language police are the worst. As someone who speaks German Nee-chee also annoys me to no end. But until my students take a philosophy class how can they be expected to know that the correct pronunciation of Nietzsche is “that Nazi bastard who prattles on about strength but couldn’t even hack the world’s cushiest job”?

Why is it necessarily dickish to mention things that outsiders get wrong? True, our incoming students might not know how to pronounce the name of a philosopher, but I don’t think the idea is to mock them for that. It’s just that it’s something that identifies people as outsiders. It’s natural that beginners will start as outsiders.

The fact that people say things like “that begs the question: what were you doing there, anyway?” is annoying and depressing in ways that it isn’t depressing to hear a philosopher’s name mispronounced. It’s annoying because these phrases were introduced to help us communicate ideas that more common phrases cannot get across very easily. We already have a familiar phrase, ‘raise the question’, that gets across what some people incorrectly think ‘beg the question’ means. We don’t need another phrase to say that. If people thought about what they were saying and avoided using phrases whose meaning they haven’t learned or looked up, our language would be clearer and more effective. Misuse of phrases like this hurts the discourse for everyone.

That doesn’t mean that everyone who misuses ‘beg the question’ is blameworthy. What used to be seen as a favor to people — helping them avoid speaking incorrectly, which also helps preserve the clarity of the language we all share — has been made into a taboo. The harm this does to communication, and to the impression such people are apt to leave, has been rendered invisible. This, together with the annoying habit of dictionary editors to write up the misuse of ‘beg the question’ as a new definition rather than a blunder, makes it impossible for people to know when they’re walking into the world with spinach in their teeth. Everyone who really knows philosophy is aware that it’s wrong, but we tend to keep it from newcomers now. I don’t see how this helps them.

In my experience correcting someone’s use of language usually has more than a bit of classism about it. That’s not to say we should never do it. One of the more valuable things I got out of college is an ability to talk like the upper class folks when I want or need to and it’s not something I’d deprive my students of. But we should be clear on what we’re doing and why. In a lot of cases it’s more like teaching how to navigate place settings with more than one fork or write a cover letter than it is helping them use language in some sort of objectively correct way much less keeping them from “harming communication.” At best it just makes it easier for us to have discussions in our classrooms. Of course I’ll tell students how I intend to use say “valid” or “begs the question” but I’m also very clear that it’s philosophers’ jargon. I’d no more fault them for using “valid” to mean “good” or “telling” outside of class than I do people who say something is “transcendent” to mean “amazingly good” rather than “pertaining to the noumenal world.”

It’d be easier for me to get sniffy about this if the last three logic/critical thinking books I’ve looked at hadn’t done an utterly garbage job explaining what begging the question even is. If some dude who expects people to pay $100 for his supposed wisdom can’t seem to get it quite right I’m going to temper my outrage when it comes to students. And I’m not sure how valuable having this shorthand really is for real world discourse. It’s not the worst thing in the world if someone has to spell out the argumentative mistakes their interlocutor is supposedly making rather than just accusing them of begging the question (or straw manning, or ambiguity, or any other fallacy). If you think otherwise I’d suggest you spend a bit more time on Reddit and observe some discussions there.

Oh, I entirely agree that people love to throw out fallacy names where they don’t apply — in fact, I encourage my own students to avoid using those terms in conversations with the lay public, and to explain the problem some other way. I also agree with you that many of the textbooks do a lamentable job of clarifying what does and doesn’t count as fallacious reasoning under this or that heading, or at all. All the more reason, I say, for clarifying what exactly these terms mean!

But please consider a parallel case. As it happens, I’m friends with a chemistry professor who always cringes when people say things like “Most loaves of bread for sale in supermarkets are loaded with chemicals.” Of course they are: if they didn’t contain chemicals, they would not exist! She makes a point of teaching her students to use terms precisely. I’m sure there are many other ways in which lay people use the terms of chemistry, physics, etc. incorrectly, and that this reveals our outsider status to people with proper training in those disciplines.

But should we conclude from this that teaching people to use words like ‘chemical’ or ‘energy’ precisely as they learn science is nothing more than a classist practice of teaching them table manners? That would sound to me to depend on the view that scientific practice can be reduced to non-truth-seeking components without loss of understanding.

Similarly, the terms we use in philosophy are meant to allow us to converse and reason with precision. If, instead, we were just showing off our group membership, then philosophy would turn out to be something quite different from what I’ve always supposed it i.

Re “the annoying habit of dictionary editors to write up the misuse of ‘beg the question’ as a new definition rather than a blunder” — this has to do with a particular perspective that at least some lexicographers have (or at any rate this is my impression from glancing at the front matter of a couple of dictionaries). The perspective is, putting it crudely, that once a particular usage becomes sufficiently widespread, it is no longer wrong. That’s not a view I entirely share, esp. not w.r.t. “begs the question,” but then I’m not a lexicographer.

“Valid” as “good” or “plausible” or as used to to express one’s agreement.

One that bugged the hell out of me — but which (mercifully) seems to have disappeared — was about a decade ago when liberal pundits used “epistemic closure” thinking it meant something like “trapped in an echo chamber”…

That was still kicking around as late as last year.

I’ve abandoned the phrase “begs the question” to the rubes who insist on misusing it, and now I just refer to the Latin petitio principii. Maybe we should start using Latin phrases (also Greek, Sanskrit, or German, if you prefer) in order to ensure that our philosophical vocabulary does not fall into the hands of the vulgar masses.

Once, I heard a student mention the great philosopher Hee-Jill several times and it took me several minutes to get what he meant

I was once had a student discuss the views of Dick Hart in their Intro to Phil essay.

“Utilitarian” used to mean “boring or ugly” rather than, well, utilitarian.