Trade Secrets: From Academic Literature to Trade Books (guest post)

Erik Angner, professor of practical philosophy at Stockholm University, has authored a book intended not mainly for academic readers, but for the general public—a trade book, as they’re known. Switching from writing academic articles and getting them published to writing How Economics Can Save the World and getting it published was a process he found surprisingly challenging.

In the following guest post, he offers help to others considering this kind of project, sharing what he wish he had known sooner about it. (A version of this post originally appeared at Angner’s Substack blog, “The Philosophical Economist“.)

[Image by Justin Weinberg]

Trade Secrets: From Academic Literature to Trade Books

by Erik Angner

You might think trade books would be easier to write than academic papers. Trade books, normally, don’t deal with super-advanced material. They don’t require fancy words. And they don’t need a thousand footnotes. And yet! I was shocked to find that writing a trade book was both harder and more painful than anything else I’ve done.

It was also harder and more painful than it would have had to be. There were many things I didn’t know about the process and the product. False assumptions tripped me up. If it weren’t for them, I probably could have finished much sooner—and with less suffering.

Maybe you, too, are an academic contemplating writing a trade book? If so, I’ve collected some impressions below. My book, How Economics Can Save the World, isn’t out yet. I can’t tell where it’ll fall on the scale from spectacular success to miserable failure. My impressions and experiences need not mirror anybody else’s. I didn’t ask my agent or publisher for their approval. But maybe this will give you something to think about.

Here are eleven things I wish I had known sooner about writing a trade book as an academic.

-

Recruit an agent

You need an agent. They’ll help you develop the proposal; identify and approach suitable publishers; negotiate the terms of a contract; give you intellectual, emotional, and moral support (as necessary) in the writing process; provide reassurance to, and request extensions from, increasingly nervous editors when you get stuck; help get you unstuck; assist in the marketing of your book; and celebrate with you when it’s done.

Some publishing houses won’t even bother talking to you if you don’t have an agent. The ones that do are likely to eat you for breakfast. As an aspiring trade-book author, you’d be negotiating a contract for the first time. The people on the other side are trained professionals who do it daily. You have little chance of getting a good deal this way. Whatever the agent costs you, it’s worth it.

Recruiting an agent is hard. Because they do almost all the work upfront, and get paid a fraction of royalties years later, they have to screen potential clients ruthlessly. A bad bet will cost them dearly. The payment schedule helps explain why publishers prefer working with clients who have a respected agent. Such authors have already survived a harsh screening process. That’s promising. Authors who do not have an agent are indistinguishable from those who tried, and failed, to find one. That’s not promising.

-

Work on the proposal, not the manuscript

What you will be selling to the publisher is a proposal. That’s a document of some 40–50 pages describing the project; the background; the audience; the competition; your previous accomplishments, skills, and credibility; the time line; and so on.

The publisher will be assessing the package as a whole. They care about the manuscript you’ll deliver. They care about the market. But they’re also interested in you—who you are, what your story is, how you will help sell the book. Convince them not just that the book needs to be written, but that it needs to be written by you.

Don’t spend too much time on the manuscript. A sample chapter is good, but save the rest for later. The reason is that your agent and publisher will have ideas about what the project should be. They won’t hesitate to tell you, and they’re likely to walk away if you’re not responsive to their suggestions. By the time you’re ready to start writing, the project will likely look very different from what you thought it would. If you complete a draft before everyone has had their say, much of that time will turn out to be wasted.

-

Think of it as a group project

It helps to think of the book as a group project. Your name alone will be on the cover. You’ll get most of the credit for things that go right, and all of the blame for things that go wrong. But many people will be involved in crafting the project.

A good agent will help you develop the proposal. They won’t pass it along to respectable publishers until it’s as good as it can be. That might require radical revisions not just along the fringes, but also at its core.

Prospective editors will do the same. They’ll tell you what they’re interested in and what leaves them cold. They’ll tell you what you need to do differently. But even then, the decision to publish will be made by some editorial board. The editor won’t put the proposal before the board before they think it’s as good as it can be.

The board, by design, is likely to be diverse. Chances are you need to win over the entire board. My original proposal was nixed by the marketing people. They couldn’t sell such project, they said, and they couldn’t use my title. They returned another title, and another project. Would I be willing to do that instead?

You can always walk away. If anyone is demanding that you to do something that you’re not willing, equipped, or ready to do, just say “Thanks, but no thanks.” That’s fine! But so can they—and they will. They do it every day.

All this might seem shocking if you’re a lone-wolf academic. You may be used to exercising complete control, from beginning to end, modulo satisfying anonymous referees now and then.

I found it helpful to think about the book as a team effort. The project is yours, but it’s not yours alone. You, your agent, your editor and publisher are all in it together. You won’t, and you shouldn’t, sell your soul. But as in every other group project, you have to be prepared to make concessions and find compromises.

-

Trust the professionals

Trust the people you’re working with. Your agent will only approach respectable publishers, who know what they’re doing.

The organization will employ a wide range of professionals. That includes publishers, editors, designers, copy editors, proof readers, marketing and publicity people, lawyers, and more.

Trust them. They’re all professionals. The publishing business is under enormous pressure. Basically anyone who works there is over-accomplished.

The professionals know more about their domain of expertise than you do. (Sorry.) They know more about what people want to read and what will sell. They know what covers and titles attract interest. They know what kind of writing works. You’re lucky to have them on your team. Let them do their thing.

You can and should expect them to respect your domain-specific expertise. You’d rightly be annoyed if the marketing people tried to correct your thesis about Victorian representations of snails, or whatever your book is about. Treat the people on your team with the same degree of respect that you expect from them.

It’s polite to ask for the author’s opinion about all sorts of things. But when your opinion is outside of your domain of expertise, your answer doesn’t really matter. They’ll trust their training and experience over your gut feeling, as they should. You won’t face a real choice until there are two effectively identical book covers, or whatever.

That’s all good! You have something you want to say, and you know what that is more than anyone. The publisher wants to get you the largest possible audience, and they know how to. You’re all pulling in the same direction.

-

Get to the point

Make your point as soon as you can. You have something you want to say. Say it immediately. Don’t leave the reader hanging.

The advice applies at the structural level. Make your point as early as possible in the text, chapter, or section. In academic writing, it’s not uncommon to gesture in the direction of the point in the Introduction, and spell it out by the end of Section 4. The non-academic reader is unlikely to have that sort of patience. Turn it upside down. Begin with the point, then provide the necessary background, definitions, clarifications, and implications later.

The advice also applies at the sentence level. Make your point in the beginning of the sentence. In academic writing, it’s common to say: “Given definition A, and under the assumptions that B, C, and D, and with the caveats that E, F, and G, it’s arguable that X.” That won’t excite the normal person. Invert the order. Start with X, then state the definitions, assumptions, and caveats later (if necessary).

Unlike academic papers, the reader of a trade book isn’t paid to read your stuff. Unlike textbooks, the reader won’t get an F for tossing it aside. You need to grab the reader’s attention—and then keep it. You do that, in part, by getting rid of the throat clearing at the beginning of every sentence, paragraph, section, and chapter.

I started thinking of myself on a layover in Detroit—tired, jet lagged, mildly hungover, and looking for some light reading. What sort of book would attract my attention there? I’d want something smart and instructive. But I’d need something that doesn’t require too much work to take in. That book would need to get to the point.

-

Make it positive

Make your thesis a positive claim, if you can. Go for “The Earth is Round” rather than “The People Who Say The Earth Is Flat Are Full of Sh!t.” It’s fine to mention ignoramuses and assholes. There’s just no reason to linger on them.

Droning on about everyone and everything that’s wrong risks alienating readers. Many of them will be unfamiliar with the alternative views. Maybe they’ll feel stupid. Many of them won’t care. Presumably they picked up a copy of your book because they want to know what you think – not what other people (possibly unknown to them) got wrong.

Going on about everything that’s wrong also risks being counterproductive. Your ambition may be to review and shoot down the arguments of your intellectual opponents. But your review might, unwittingly, have the effect of drawing the reader’s attention to all the people, and arguments, on the other side. “No smoke without fire!,” the reader might say to themselves. You’ve shot yourself in the foot.

-

Make it simple

Aim to write at a junior-high-school level. Simple writing is good for everyone. It’s critical if you want to reach an audience without a high-school degree. But it’s also good for people who have one. Research suggests that even people with PhDs retain more information if the text is written at this level.

Writing at a junior-high level is hard. Use short sentences. Use a direct sentence structure. Try to turn subordinate clauses into separate sentences. Eliminate “howevers,” “meanwhiles,” “consequentlys,” “in other words’s”, and “to be clears.” Use everyday language and avoid technical terms. But don’t go overboard. Passive sentences, subordinate clauses, technical terms, etc. serve a purpose. Occasional longer sentences help break up the monotony.

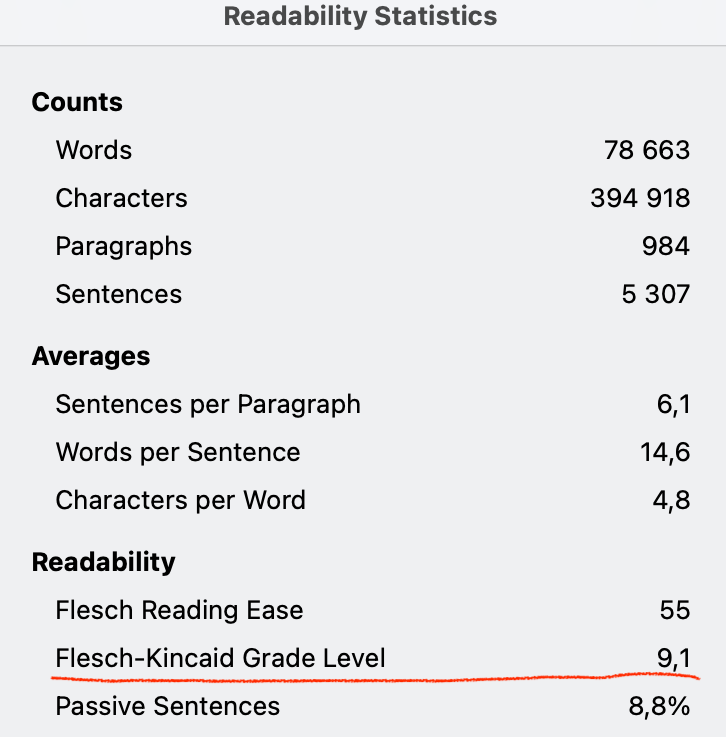

MS Word can calculate the reading level of your text for you. Just activate the spell checker, and hit “Document stats.” Look for the “Flesch–Kincaid grade level.” If you’re curious, this post was written at a sixth-grade reading level. That’s the target.

The picture shows the readability statistics of How Economics Can Save the World. I managed to get it down to a ninth-grade level. I wish I could have done better. But it could have been worse. If you have a competitive streak, you can aim, in your own work, to do better than I did.

Readability statistics for How Economics Can Save the World

-

Make it short

Short chapters, sections, and paragraphs are good. They break the text into chunks. That makes it easier to process. They also provide for more white space. That’s easier on the eyes.

You don’t need to record every thought you’ve ever had on the topic. The reader probably assumes your smart and knowledgeable. You don’t need to prove it, and don’t want to disappoint them.

My favorite example is Welcome to Your Child’s Brain, by Sandra Aamodt and Sam Wang. It runs 336 pages and has 30 chapters. Its target audience consists of new parents, who tend to be exhausted and sleep deprived. That’s certainly the state I was in when I read it. The short chapters (of about ten pages each) were perfect. They contained enough information to be interesting, even exciting. But they were short enough that I could finish one before passing out.

Here’s some white space.

Here’s some more.

-

Tell it with stories

Stories are the best way to convey information. Use them generously. Stories grab the reader’s attention and retain it. They direct the reader to phenomena of interest, underscore puzzles, and suggest solutions. They can be used to illustrate abstract points and general implications.

Just make sure the stories lead somewhere. Since you’re writing non-fiction, rather than a collection of short stories, the reader expects them to point toward some more general insight or argument. There’s a place for generalizations and abstract reasoning. But allow it to play second fiddle.

The stories can be fictional or real, from your life or the news, from literature or the movies. It doesn’t matter. Try to tell them as compellingly as you can. Then make them count.

-

Say what you want the reader to do

Professional writers, from journalists to marketing people, are used to answering the question “What do you want the reader to do with the information?”

Readers want to know what they should do with the information. How should the information you’re communicating influence the way they approach the world and live their lives? How does it help them build a better world? Be explicit.

In my discipline it’s common to end papers with a sentence such as “This analysis can help us promote equality.” The trade-book reader wants to know how, exactly, that’s supposed to work. What’s the process that starts with reading the book and ends with a more equal world? Explain and give examples—preferably by means of stories.

A book that gives the reader a clear basis for action gives them an additional reason to pick up your book, as opposed to any of the thousands of other ones in the store. You think the topic is so interesting that any one should want to read it for that reason alone. There’s a good chance the reader isn’t quite as curious as you are about the particular thing you’ve chosen to study for years or decades. But even if they are, give them reasons to care.

-

Remember your audience

Remember who you’re writing for. It’s the general public.

The target audience does not include your colleagues in academia. If you’re like me, it’s very hard not to think about their reactions. We’ve been conditioned to care about the approval of our tribe our entire professional lives. But now you need to ignore them.

Obviously you’ll want to retain the respect of your colleagues by getting your facts right. You’ll want to be honest and transparent about your competence and its limitations. You’ll want to acknowledge the contributions of others. The principles of research ethics still apply.

But you will have to simplify, leave out detail, use everyday language, and so on. Your colleagues who don’t understand the nature of the project may disapprove. You’re going to have to learn to live with that.

The pleasure and the joy of writing a trade book comes from the act itself—alongside any approval and appreciation you may receive from outside your profession. Maybe.

Final remarks

I’m not telling you, or anyone, that they should write trade books. It’s obviously not for everyone, and the rewards may be scarce. But on the whole, I wish more academics did. There are many charlatans and cranks out there churning out popular books. There’s a market for them, because there’s great demand and limited supply of more serious contributions. The best way to deal with the charlatans and cranks is not to whine about them, but to undercut the market for second-rate contributions.

If you’re up for it, give it a shot! In the meantime, if you have questions, or comments, feel free to share them below.

Great advice. And timely! I’m just a few days from the beginning of a sabbatical and one of my main goals is to write a trade book. Can you say more about how you found your agent?

Hi William: I was lucky enough to know one well, since he’d been my editor and publisher for another book project. My best advice is to use your network: see if you can find a successful author who can introduce you to their agent and vice versa. Relationships count for a lot! Best of luck with your project.

I’m in a similar position to William V., and I’m overwhelmed by the number of opinions online regarding literary agents. I suppose it would be good to speak with one… if only I knew how to find one that would speak with me.

Yes, it can be a challenge. But remember that at least part of their job is to recruit and support new authors. They do have an incentive to talk to you!

Work from books -> agents. Find titles like your would-be title that have been published and use them and some creative Googling to figure out who agented them. Don’t be beyond even calling up the publishing house and asking them.

First, thanks Erik for this great post! I’ve also been lucky enough to have an agent and can underscore the importance of finding one to this process. It’s worth pursuing whatever angle you can, but I think in the ideal world the agent prefers to “find” you, which points to the importance of getting your (accessibly written!) ideas out there in whatever public venues you can find.

5-6, and to some extent 7-9, are also good advice for academic writing.

I think 4. is really important. But also hard for academics to do, since we’re so used to really tight control over our ideas and how they’re expressed! I recently published a book that is a kind of trade / academic hybrid, and my editor wanted us to use a title that I really wasn’t sure about. But it turns out she was completely right, and that title has undoubtedly helped capitalise on interest in the book. Generally, my philosophy has become: trust them, they’re really good at their job, and they know a great deal more about finding an audience than we do.