Co-Authorship in Philosophy over the Past 120 Years (by Bourget & Weinberg)

“We think philosophy is due an ethos change; one where the myth of the ‘lone genius’ is dispelled and where co-authoring is both encouraged and acknowledged.”

Those are the words of Matyáš Moravec and Peter West (Durham) in a recent essay at The Philosopher, in which they discuss some of the advantages of philosophical co-authorship and urge more of it. Perhaps they’ll be pleased that this post is co-authored.

[Valentine Hugo, André Breton, Tristan Tzara, Greta Knutson – “Cadavre Exquis”]

That there has been more discussion of the lack of co-authorship in philosophy recently had one of us thinking that co-authorship was in fact on the rise: up to a point, an increase in instances of co-authorship in philosophy would get more people thinking about it, and some of those thoughts would be “there’s not enough of it.”

That one of us—Justin—approached the other one of us—David—for help in acquiring actual data on co-authorship in philosophy. That was a good call on the part of Justin, if we don’t say so ourselves, because David is one of the creators and editors of the amazing, if we don’t say so ourselves, online repository of philosophical research, PhilPapers.

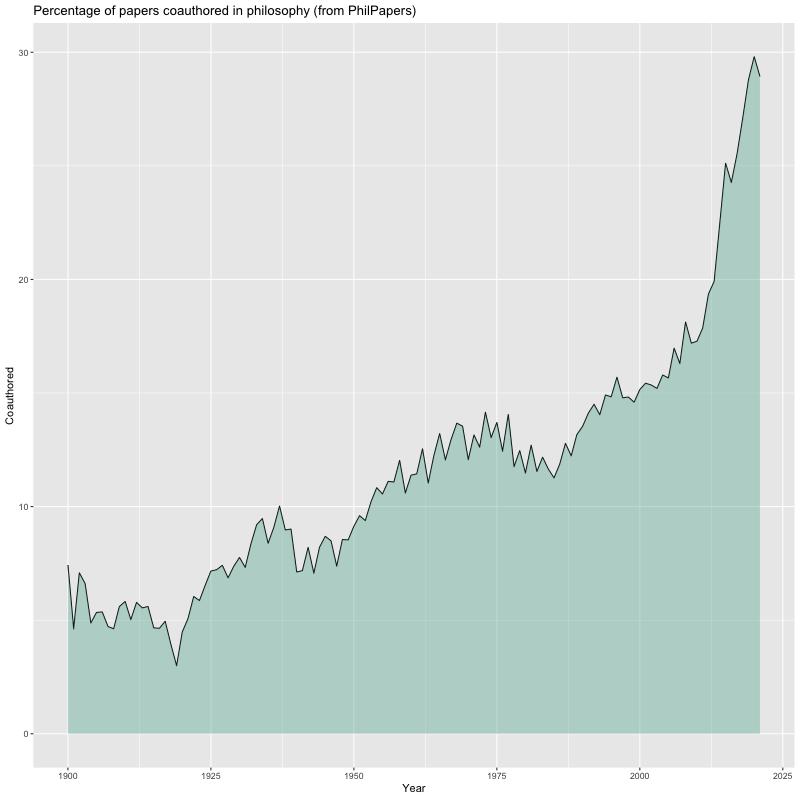

Here’s what we—that is, David—found: co-authorship of philosophical works rose from around 7% in 1900 to just under 30% today, with two-thirds of that growth happening since 2000:

Two notes about this data. First, it is based on works in the PhilPapers database, which has some limitations as a data source for present purposes, such as a focus on English-language publications. Second, the data includes a wide range of types of philosophical publications. When the search was limited to just articles published in a limited set of well-known philosophy journals, the rise was from around 5% in 1900 to around 17% in 2021, with again around two-thirds of that growth occurring over the past two decades.

What has caused this recent steep increase in co-authorship in philosophy? Closer examinations of the co-authored pieces might reveal some answers. One could investigate whether the growth of co-authoring has been more pronounced in certain subfields or on certain topics, or is correlated with increased acceptance of interdisciplinary work in philosophy, or is tied to the use of particular methodologies or tools, or is more common on works that emerge from large-scale grants (like those from the Templeton Foundation, which was founded in 1987), and so on. Other factors may have also played a role, such as the development, through computers and communications technology (email), of rapidly shareable and easily editable manuscripts. Maybe economic conditions have a direct or indirect effect (e.g., increased competitiveness in the job market has spurred an increase in publications by graduate students, and perhaps these are more likely to be co-authored, particularly with mentors). And broader changes in the culture of academic philosophy, from more adversarial to more cooperative, may have played a role here, too. At this point these are just speculations, though.

In their piece, Schliesser and Miller cite data from 2012 showing philosophy is one of the disciplines with the least amount of co-authoring. Though half the growth in co-authorship in philosophy over the past 120 years took place between 2012 and 2021, we do not at this time know whether philosophy’s position relative to other disciplines, in terms of the prevalence of co-authorship, has changed during this period.

Even if it hasn’t, the significant increase in co-authorship in philosophy, especially since the turn of the century, raises the question of whether the “ethos change” Moravec and West call for has in fact already occurred.

by David Bourget (Western University) & Justin Weinberg (University of South Carolina)

with assistance from David Chalmers (New York University)

I suspect that if you subtract out all of the work by experimental philosophers (which began in earnest in the early 2000s), there will be little co-authorship in philosophy more generally. It’s just a hunch.

thomas: the numbers already disconfirm that hypothesis. the philpapers database includes 2462 articles categorized as experimental philosophy, which is about 0.1% of the database. even once restricted to since-2000, selected journals, etc, and assuming that only half the articles in x-phi are categorized (implausibly low since our x-phi editors are very dedicated), x-phi articles are still not more than 1-2% at most. even if they’re all coauthored, experimental philosophy can account for at most a smallish portion of the 8-16% rise in coauthorship since 2000.

As could be predicted from Dave’s comment, I get the following percentages of coauthored papers from 2000 when excluding xphi (using PP categorization):

2000 0.1514

2001 0.1542

2002 0.1535

2003 0.1520

2004 0.1578

2005 0.1564

2006 0.1696

2007 0.1627

2008 0.1809

2009 0.1713

2010 0.1722

2011 0.1781

2012 0.1925

2013 0.1982

2014 0.2242

2015 0.2505

2016 0.2417

2017 0.2544

2018 0.2704

2019 0.2867

2020 0.2966

2021 0.2871

Is it possible to search PhilPapers based on co-authorship? I know you did it, but it’s not clear how you did it. I couldn’t figure out how to do so. I’d like to take a look at all of these co-authored non-experimental papers! I’d also like to see the list of the limited set of well-known journals if you don’t mind posting them here.

It’s not possible using the public tools (I have direct access to the underlying data).

It’s fine that I can’t take a look to see for myself what the data look like–and see where all of this co-authored yet not-experimental research is being published–but I assume that you can make the list of the journals that y’all designated as well-known public since (a) it’s helpful to see what you and David count as well-known (and not well-known),and (b) so I can search through these well-known journals to look for co-authored papers.

since there’s alot of interest, perhaps you could post the data on osf.io or another open repository

Yes, that would be helpful–especially if the data are going to be used in the way it has been used in this thread.

Are there also more papers being published generally?

Here’s a hypothesis in the vicinity of Thomas’, which cuts across area demarcations:

Papers representing a naturalistic orientation typified by (reasonably) close engagement with science are overrepresented among collaboratively authored philosophy papers.

I’m unencumbered by evidence here (as perhaps befits a singly authored post!), but the hypothesis does fit my sense of who the most active philosophical collaborators are.

I’m not sure testing it would be worth the labor, but I think it would be interesting if it were false.

Really interesting Be great to subset by field – id guess Phil of mind in collab with psychologists is the biggest source.

Also interesting to check:

1. If the collabs are between several philosophers or between philosophers and other disciplines (and if this depends on field – maybe you could use dept as a proxy for field, like if the authors are in philosophy dept versus linguistics dept)

2. If the age of the other discipline as an academic subject predicts collaboration. So, linguistics and psychology are both recent departures from philosophy , whereas physics became its own thing much less recently . Age of the ‘first dept’ for partner disciplines could predict likelihood of collaborations (more recent depts more likely to collaborate?).

good suggestions! maybe when i have a little more time on my hands we can do a follow up post.

“… if we don’t say so ourselves …”? But you do say so yourselves! Is this what happens when you co-author, huh? The shift from singular to plural introduces an errant negation into your conditional propositions, like some sort of unhinged grammatical Bolshevism? If so, then don’t count us out!

In this brave new world, up is down, 2 + 2 = 5, to say “we don’t say so ourselves” is not to not say so ourselves, and we can switch between the literal we and royal we as we see fit.

This is great! Happy to have prompted this research!

One thing that has struck me since me and Matyas wrote this article is that *even if* co-authoring is more common (which evidently it is), the prevailing image is still of a lone philosopher. I wonder to what extent this might have to do with the way we teach especially the history of philosophy as a line of ‘great thinkers’.

My dissertation advisor and I co-authored a paper for The Monist. And it had nothing to do with experimental philosophy. It was by far the single greatest learning experience I had as a grad student. I’ve long said that philosophy needs to foster joint prof-grad work like so many other disciplines do. I don’t see any justification for the hold-up, except for some mythic poppycock along the lines of “good philosophers fly alone, like eagles.”

I wonder if one’s regard for co-authorship depends upon how one views the writing of philosophy. (This is on my mind after reading a previous post here about linguistic norms in philosophy.)

For example, one might think of a piece of philosophy as a report, from no point of view in particular, on how things can or cannot be, or must or must not be. If so, one might be less inclined to see any problem with co-authorship. It’s just several relatively well-calibrated instruments claiming to bring us the news about necessities, after all — not essentially different from one relatively well-calibrated instrument.

Do these figures exclude co-authored prefaces or introductions to special issues and books, for instance?

We attempted to exclude journal frontmatter (as well as reviews). We don’t generally have book prefaces as individual index items. The figure reported is the percentage of qualifying PhilPapers entries.

For P&T, my university required me to get my co-authors to write letters attesting to my role in published papers. I found asking colleagues for those letters to be deeply embarrassing. It makes me not want to do it again.

The tenure process is apt to be embarrassing regardless. Don’t let this discourage you from coauthoring!

As P. D. says, SMJ, please don’t be embarrassed. Soliciting information about contributions is standard procedure for many personnel committees, so such requests are quite standard, and should be viewed by collaborators, esp. senior collaborators, as a routine part of their job.

Indeed, in as much as one’s collaborators tend to think well of one, the practice is actually in the candidate’s interest, since the collaborator can easily drop in a few words of endorsement along with the estimation of contributions, in effect adding a positive “mini-letter” to the file.

On Twitter, a famous philosopher reports:

“When I was an assistant professor, an extremely eminent philosophy professor told me, in response to me telling him that the paper I was working on was co-authored, that “no work of genius can be co-authored.” I’ve always thought that remark provides a nice window on my field.”

No wonder co-authorship has been so slow to catch on…

Whitehead and Russell would certainly be more than competent to symbolize and analyze “no work of genius can be co-authored.” And though outside our field, I regard Michelson and Morley as a good joint candidate to falsify that claim. Not to mention EPR. . .

That remark just goes to show that, like everyone else, extremely eminent philosophy professors, while no doubt extremely intelligent, can also be, at the same time, extremely dumb.

Should a philosopher want to produce a work of genius? Is producing a work of genius the telos of philosophy? Is one’s philosophical activity meant to be measured according to how close one comes to producing a work of genius?

Perhaps it’s only if you give a (qualified or unqualified) affirmative answer to those questions that you’d think that *not* producing a work of genius is to fail as a philosopher, in no matter how small a way.

And thus that it’s somehow distasteful to suggest that not all philosophers (or aspiring ones) are graced with the fortune to produce works of genius.

And thus that it’s distasteful to suggest that a co-authored superposition of philosophical voices is unlikely to yield the kind of singular vision that characterizes so many of our inspired forebears.

(Not that there can’t be such co-authored works, of course. (See: Russell and Whitehead). I mean for my comment to addressing the sources of the palpable offense caused by the suggestions, not the truth-value of the suggestions.)

I reported on the rates of collaboration in the journal Philosophy of Science in my paper “The Epistemic Significance of Collaborative Research,” published in Phil. Sci. in 2002.

Only 1 out 143 articles published in the first five years of the journal (1934-1938) were co-authored. Between 1990 and 1994, 22 of the 194 articles in the journal were co-authored (that is, 11 %). So philosophy of science has been collaborative for some time. No doubt it is partly due to the influence of science – people like David Hull, for example, were active scientific researchers.

I like coauthoring and do it all the time. I also don’t work in any of the sub fields mentioned above (I mainly work in epistemology). One nice thing about the uk is that coauthorship doesn’t matter much when it comes to the REF: you can submit your coauthored piece in the same way you would a solo piece (unless you and your coauthor are at the same institution-you can’t both submit the same piece). Means I really have no incentive to not coauthor, beyond the silly attitudes of some philosophers towards coauthoring.

If co-authorship is going up in philosophy is it time for philosophy journals to start implementing compulsory authorship contribution statements, as is becoming more common in the natural sciences?

Rose

I think this is a mistake. Recently, a colleague and I argued against authorship contribution statements EVEN in science. Our paper is forthcoming in Episteme (it is available On-Line First). If you have worked collaboratively, you realize it is quite artificial to parse out the various contributions and assign them to one person (or two). Collaboration is often not like that at all.

Here’s an idea: introduce a philosophy-equivalent of the Erdős number. Seems to work for the mathematicians. We just have to think of a philosopher that was prolific and co-authored a lot. Suggestions?

Some of us already have finite Erdos numbers. 😉

Mine is five … nothing special

John Hawthorne would be a natural candidate if you’re happy with someone still active.

John’s CV certainly reveals hm to be an extraordinary collaborator, Brian (and makes one counter example to the above speculation that philosophical collaborators tend to be empirically inclined).

I wonder if playing the Erdős number game in philosophy would reveal the field to be “siloed,” with comparatively tight research circles. Would someone with a relatively low “Hawthorne number” tend to have a relatively high (to take another extraordinary collaborator) “Stich number” (and vice versa)?

I can bound Stich’s Hawthorne Number (or vice versa) at 6:

Mallon, Machery, Nichols, and Stich, PPR 79 (2009) pp.332-356.

Knobe, Lombrozo and Machery, Rev.Phil.Psych. 2 (2010) pp.157-160.

Khoo and Knobe, Nous 52 (2018) pp. 109-143.

Mandelkern and Khoo, Analysis 79 (2019) pp.424-436.

Mandelkern and Rothschild, J.Philos.Logic 50 (2021) pp.89-96

Hawthorne and Rothschild, Philos.Stud 173 (2016) pp.1393-1404

Edit: I can get it to 5 if we use Knobe, Machery and Stich, Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research 34 (2017) pp.443-445. (But it’s a guest editorial, and I don’t know if that counts.)

Here’s a path of 4, though I suspect it could be lower – there are so many Rutgers connections. (Does Oxford Studies count? I’m not sure of the rules.)

Stich, Rose and several others Thought 6 (3): 193-203. 2017.

Rose, Turri and Buckwalter Philosophical Studies 175 (10): 2507-2537. 2018.

Benton and Turri Synthese 191 (8): 1857-1866. 2014.

Benton, Hawthorne and Isaacs Oxford Studies in Philosophy of Religion 7 1-31. 2016.

I think the answer is yes about silos but the number isn’t the right way to measure them. All it takes is one person to connect the two, and since Hawthorne and Stich had lots of grad students in common it wouldn’t be surprising if there are links between the two. Probably we should be looking at something like what proportion of their collaborators collaborate with each other rather than with people from the other silo.

And if we did that I think you’d be right about silos.

I wouldn’t want to make any general claim about silos in philosophy, but it does seem like the two specific philosophical approaches we’ve been discussing here are *much* less siloed off from each other than they used to be.

The thing emerging from the chain David Wallace created and the chain Brian Weatherson created doesn’t seem like just some cute little trick. Instead, it seems like the philosophers connecting the two sides of the chain (Mandelkern, Khoo, Rothschild, Turri, etc.) genuinely are building a bridge between traditional research in core M&E and more empirically informed research of the type one finds in experimental philosophy.

Elliott Sober has probably co-authored with at least 40 different people over the years – not as many perhaps as Hawthorne but close and Sober also has many more total pubs.

The original Moravec and West paper (from which the current post’s introductory paragraph is drawn) is I think wrong about several aspects of the research culture in physics, but in an interesting way. They write:

“It is, of course, possible to find equally well-known lone-figure scientists (like Feynman, Hawking, Eddington, or Brian Cox). But it is questionable whether such figures are known for their research as opposed to public appearances or other science-popularising activities… Nobel prizes in literature (which have been awarded to philosophers, such as Bergson in 1927 or Russell in 1950) have only ever been given to individuals. Those in physics almost always go to teams of people. This indicates that when it comes to the research, the popular conception of lone scientific geniuses is off the mark; scientific progress requires collaboration.”

1) I’m not sure it’s true that Nobel prizes in physics ‘almost always go to teams of people.’ Picking the three recent ones where I know the background enough to judge:

– the 2020 prize (for black hole physics) went to Roger Penrose, Andrea Ghez, and Reinhard Genzel. None of these collaborated with each other: Penrose was receiving the prize for his (mostly single-authored) work on the theory of black holes decades previously; Ghez and Genzel ran separate observational teams.

– the 2017 prize (for gravitational waves) went to Kip Thorne, Barry Barish, and Rainer Weiss. Thorne and Barish did some of the key early work in developing gravity wave detectors, and as far as I can tell didn’t publish together. Weiss led the LIGO project, much later on.

– the 2012 prize (for the Higgs boson) went to Francois Englert and Peter Higgs, who – in separate papers – developed the theory of the Higgs mechanism.

At least in these cases, when the Nobel prize committee awards the prize to multiple people it’s recognizing that multiple people deserve credit, not recognizing explicit teams.

2) Feynman, Hawking and Eddington are really major figures in 20th century physics primarily because of their research; that they had successful careers as popularizers isn’t their main claim to scientific status. (Feynman shared the 1965 Nobel prize for his work on quantum field theory, for instance.) And Feynman and Hawking, at least, have some single-authored papers and some joint-authored papers – their scientific work is not noticeably more or less collaborative than other major theoreticians.

3) Many of the most important papers in theoretical physics in the postwar period were joint-authored; equally, many others were single-authored. It really isn’t true that research here requires teams of people.(Experimental physics usually does require teams of people, but the reasons there are logistical and don’t carry over to philosophy.)

4) The much higher levels of collaboration in physics are *partially* (by no means entirely) because physics has a much lower bar for what counts as co-authorship. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that someone who got generously listed in the acknowledgements of a philosophy paper would be listed as a co-author under physics conventions.

5) Theoretical physics has at least as much tendency as philosophy to identify a smallish number of people who are taken to do exceptionally important and high-quality work. (Without prejudice to whether that’s good or bad, or indeed whether it’s true or false.)

—

All this said, what is true about Moravec and West’s paper is that physics is highly collaborative, not always in the sense that people are working and writing in teams, but in the sense that everyone is engaging closely with everyone else’s work. Insofar as philosophy involves ‘lone geniuses’ pursuing their own project in only intermittent communication with others, physics definitely doesn’t do that. But of course, if that’s our model for collaboration then at least many areas of philosophy are also collaborative in that sense.

Some coauthorships are predatory. Coauthorships inflation is occurring in every discipline because it lets senior people get credit for little to no work.

Glad that collaborative writing in philosophy is getting noticed. Brickhouse & Smith immediately come to my mind as a successful collaboration, contributing to the history of philosophy about Socrates. I’m wondering about interdisciplinary collaboration in philosophy, if it will be as received as collaborative writing within the discipline? I’m currently working on a paper with two mathematicians, so, it seems they would be outside my research in ancient philosophy, yet we are writing about geometry in Greek philosophy. It is amusing to work with contemporary mathematicians, as they say, “well, it is obvious, so we’ll let the reader work it out for themselves,” and I respond, “well, no, we have to spell it out, otherwise we leave ourselves open to straw man objections.” Only in the philosophy of mathematics have I heard philosophers say, “it is obviously true.” Collaborative writing across disciplines, at least in my experience, opens doors to new ways of thinking and approaching solutions to problems. So, yes, let’s do more of it.

Regarding this phrase, which I increasingly see outside analytic philosophy: “the myth of the lone genius.” What does this refer to? Is it that anytime one imagines a lone genius (Kripke or Kamm or someone like that having an epiphany in an office) it is false? They weren’t really geniuses or weren’t really acting on their own? Every time? Or does it extend farther, to people generally, the idea being no good intellectual contributions are arrived at by individuals on their own? Or is it a weaker and watered-down version of these: in general, good intellectual contributions are arrived at in collaboration with others, so that it (often, in general) is unclear where one person’s part ends and another’s begins?

On any interpretation, the phrase is unhelpful. The last interpretation is banal and, even if true, fails to support the word “myth,” which evokes a phenomenon that doesn’t really exist. The others are too strong, though: surely there are individuals having brilliant ideas on their own at least sometimes. This is especially true in fields like analytic philosophy where a single hypothetical (in some of Philippa Foot’s or Judith Thomson’s work) or pointed observation (Bernard Williams) or nagging doubt (Thomas Nagel) could count as a game-changing contribution. There is no good reason to deny that, in such cases, the individual philosopher has a good idea — and it is hers alone, at least in the sense that an idea can be someone’s in particular — and then works it into a good contribution.

So, again, what is this myth that’s become so often referenced?