Faculty at Rhodes College Urge Cancellation of Online Talk by Peter Singer (updated)

The Department of Philosophy at Rhodes College is scheduled to host an online event tomorrow (Wednesday) afternoon on pandemic ethics, featuring a conversation with Peter Singer (Princeton) and the philosophers at Rhodes. Faculty in other departments at the College have called for Singer’s invitation to be rescinded, owing to their understanding of his views about disability.

A flyer for the event featuring Peter Singer.

Faculty in the Department of Anthropology and Sociology and the Africana Studies Program sent out an email to the college community that said, in part:

We, the faculty in the Department of Anthropology and Sociology and the Africana Studies Program, wish to express our deepest dismay at the invitation of Professor Peter Singer to our campus. We believe that proceeding with this event as currently structured could further alienate students, faculty, and staff, particularly after the unresolved racist “incident” [story here] against African Americans that occurred in early September.

Professor Singer’s longstanding advancement of philosophical arguments that presume the inferiority of many disabled lives is dehumanizing and dangerous. The creation of a hierarchy of lives as a justification for the allocation or denial of limited resources (whether “pleasure,” medical care, insurance, etc.) is a logic that has a long and violent history. It is a logic that underlies eugenicist arguments marking various marginalized populations as unfit to be a part of the advancement of the human race…

Disability scholars have critiqued Singer’s body of work across a range of themes, and we encourage anyone who reads Singer to also read this rich scholarship. Salient among these themes for the purposes of a panel on pandemic ethics is the denial of some disabled people’s full humanity and the premise that certain disabled people have lives that are less worth living than “normal” people (with whom they might be competing for medical resources). Given that COVID is one of the most profound disability rights issues of our lifetimes, it would seem that any panel on pandemic ethics would include disability scholars (especially given their significant challenges to Singer’s credibility in this area).

Rather than suggesting an alternative structure to the event such as the inclusion of one of the aforementioned disability scholars, though, the faculty instead says:

[W]e affirm our dedication to disability justice and urge the college to withdraw the invitation. We stand next to our students who are working hard to fight for their ideals of equality, fairness, and diversity, not as lip service, but as the basis of reflection and action. We cherish and advocate for freedom of speech and expression as long as it does not deny others their humanity.

Some history faculty also sent out an email objecting to the event:

As historians, we the undersigned condemn Prof. Peter Singers’ abhorrent views that some humans have less value than others. We object to inviting him to Rhodes College to speak as part of a “Pandemics Ethics” panel. Positioning him as an expert on ethics only legitimizes his reprehensible beliefs that deny the very humanity of people with disabilities. Hypothetical philosophies on morality cause real violence. We historians are all too familiar with ideas that justify labeling marginalized, vulnerable, and minority populations as “life unworthy of life,” and the murderous consequences for those deemed “unfit” to live. Adhering to the College’s own IDEAS Framework that seeks to foster “a sense of belonging” and embrace “the full range of psychological, physical, and social difference,” we historians assert that Prof. Peter Singers’ blatant inhumanity has no place in serious academic exchange here at Rhodes.

While statements of support for people with disabilities is of course laudable, and criticisms of Singer’s views may be worth making, it is unfortunate that these faculty chose to combine this expression of solidarity with a call for action that would violate the academic freedom of their colleagues in the Department of Philosophy.

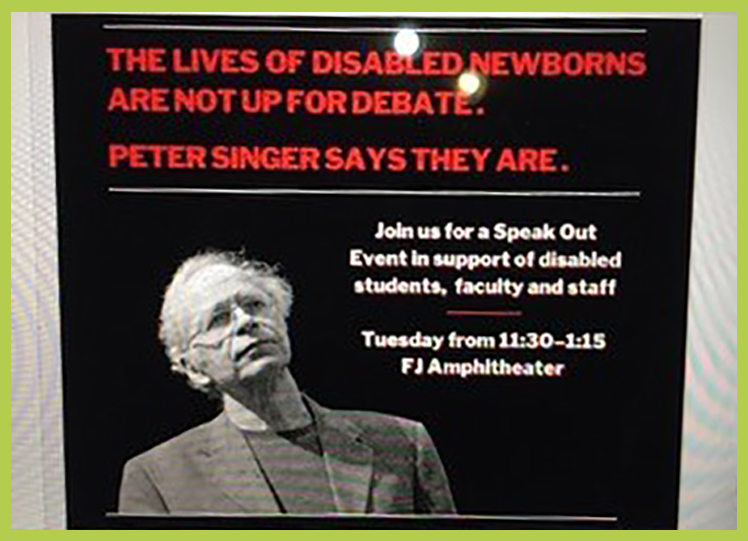

Photo of a sign for a “speak out” in support of persons with disabilities at Rhodes College.

Fortunately, the Rhodes College administration did not cancel the event. Rather, apparently with the view that the best response to problematic speech is more speech, the interim president and provost wrote the following:

Yesterday a member of our faculty informed us of his profound disturbance caused by the invitation of Princeton University Prof. Peter Singer to speak on a Rhodes “Pandemic Ethics” virtual panel next week.

We are writing to acknowledge that our institution’s spirit of supporting expressive speech does not prohibit Professor Singer’s participation in this virtual panel. At the same time, our community’s values compel us to denounce some of the views he has expressed repeatedly over years through various addresses, writings, and media interviews.

Fundamentally, Rhodes College is deeply committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion. These values extend to every member of our community, including individuals with disabilities. While we view the invitation to Peter Singer in light of our commitment to free and open dialogue at a liberal arts college, his views on disability are unequivocally antithetical to our institutional values of diversity, equity and inclusion. We reject and condemn in the most forceful manner possible any views that call into question the value and worth of all human life. It is within this context that we make the following affirmations:

-

- We affirm our strong belief in an inclusive, diverse, equitable, and accessible community – as outlined in the College’s IDEAS framework – one in which the worth and dignity of all persons is championed and supported.

- We affirm particular support for disabled members of our community who, justifiably, have expressed anger, outrage, and offense at some of Prof. Singer’s writings. Not only does Rhodes not tolerate discrimination on the basis of disability, the College also strongly believes that disabled people enrich our community by their presence on our campus. We affirm this while recognizing that we still have much work to do as an institution to support individuals with disabilities.

As an academic institution, we re-affirm our Statement on Diversity, which expresses our commitment to providing an “open learning environment,” where “freedom of thought, a healthy exchange of ideas, and an appreciation of diverse perspectives” are fundamental. It is this commitment to freedom of expression that allows academic departments to invite a variety of speakers to campus to enrich the educational experience of our students. Nevertheless, they should do so with responsibility, as well as with careful attention to our values as a diverse, equitable, and inclusive institution.

The Department of Philosophy at Rhodes is chaired by Rebecca Tuvel (who readers may recall from this controversy). In response to an earlier call to rescind Singer’s invitation (see update 1), she emailed a statement from her and her departmental colleagues to the college community:

We write in response to one of our colleagues, who has publicly expressed concern about the Philosophy department’s invitation to Peter Singer—and he has every right to do so. The objection raised is apparently not to the topic, but to the speaker. We are of course aware that Professor Singer has advanced philosophical arguments on bioethical issues that many find not only disturbing but deeply offensive, a reaction by no means confined to members of the disabled community. Indeed, the organizers also take issue with some of Dr. Singer’s views.

Serious intellectual exchange about matters of significance cannot avoid sometimes causing anger, offense, and pain and no one should be cavalier about that fact. It is not clear to us, however, what follows from our colleague’s understandable expression of disturbance at some of Professor Singer’s views. Do those views disqualify Singer from participating in the exchange of ideas that ought to occur at a liberal arts college? If that is the conclusion, we respectfully disagree, for its premise is that ideas that cause anger and dismay ought not, for that reason, be part of the exchange and that premise, we think, is incompatible with our mission to teach students how to engage in productive dialogue even, and indeed especially, with thinkers with whom they vehemently disagree.

It’s an excellent response.

A speak-out in support of people with disabilities at Rhodes College was scheduled for earlier today.

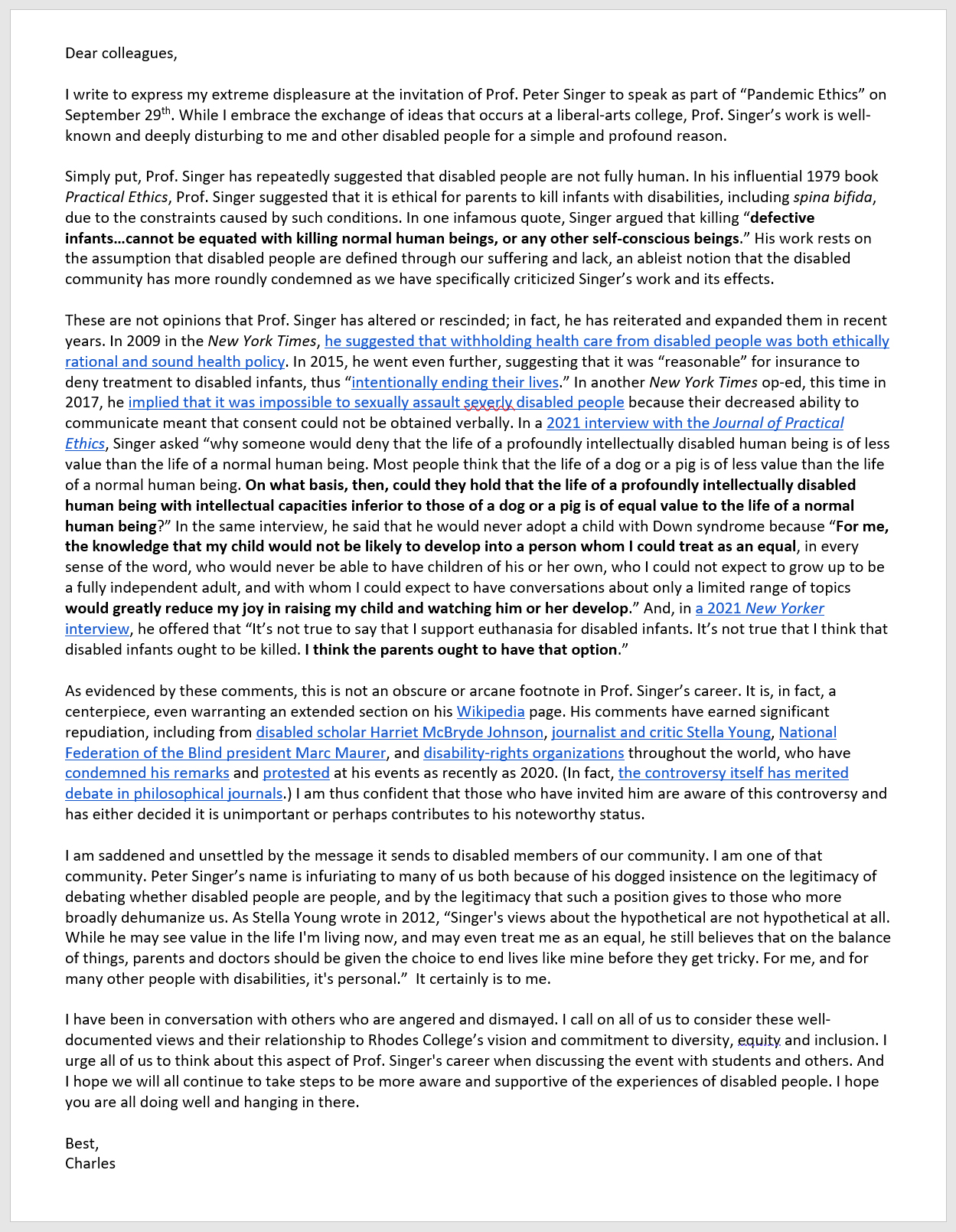

UPDATE 1: Professor Tuvel has clarified that the email from her and her colleagues was sent out prior to the other emails mentioned in the post. It was sent in response to the following email from Charles Hughes, Director of the Lynne and Henry Turley Memphis Center at Rhodes College:

(PDF of the above letter here.)

After the controversy surrounding the event with Singer grew, Dr. Tuvel sent out a different email to colleagues around campus clarifying Singer’s views, concluding:

I realize that now is not the time to get into the weeds of Singer’s utilitarian ethics. Should there be interest at some point down the line, I would be more than happy to organize a reading group and/or zoom event where myself and other members of the Philosophy department can clarify Singer’s views on these incredibly sensitive topics. At some point, I think our community would also benefit greatly from an event devoted to discussing these delicate matters. On pains of intellectual and moral failure, such an event would absolutely need to include experts in disability rights (such as Professor Charles Hughes), parents of children with disabilities, and relevant others…

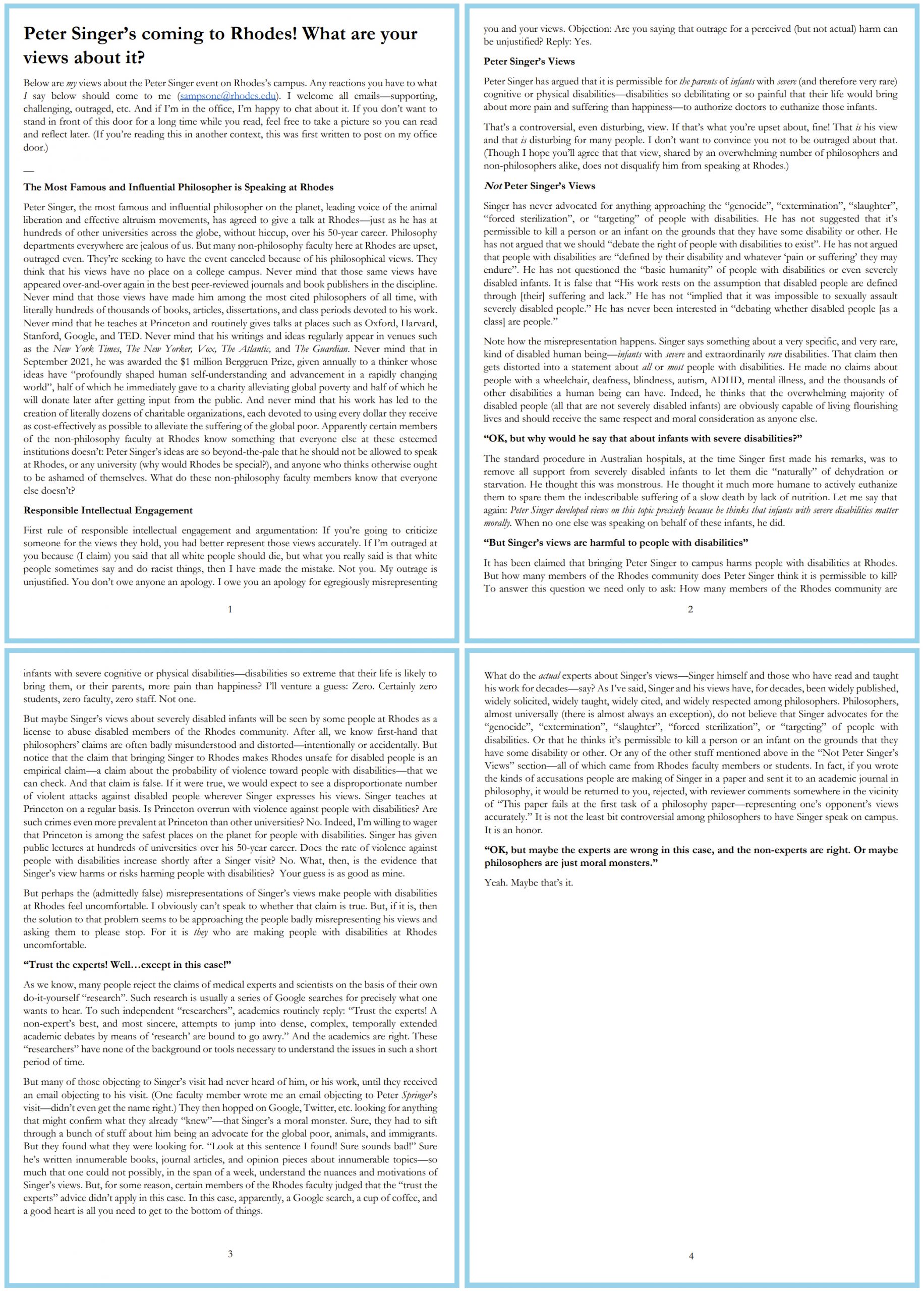

UPDATE 2: Eric Sampson, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Philosophy at Rhodes, wrote up a document clarifying Singer’s views for others at Rhodes and defending the decision to invite him to speak:

You can view Dr. Sampson’s document as a PDF here.

You can view Dr. Sampson’s document as a PDF here.

UPDATE 3 (9/29/21): The word “some” was inserted at the start of the paragraph about the email from history faculty after it was brought to my attention that not all of the history faculty signed onto it.

“If that is the conclusion, we respectfully disagree, for its premise is that ideas that cause anger and dismay ought not, for that reason, be part of the exchange”

That is clearly NOT the premise. The reasons given are not about the emotions of those calling for Singer to be disinvited, they are about the content of Singer’s views. Feelings of anger and dismay are not mentioned anywhere in the reasons given for disinviting Singer. The closest is the mention of student alienation in the first. The core reasons have to do with claims that Singer’s views are dehumanizing and harmful.

You might, on principled grounds, agree that academic freedom rules out the call for a disinvitation. You might, on substantive grounds, hold that Singer’s critics misrepresent or misunderstand his views. But calling this an excellent response is like calling an “Well I’m sorry you got upset” apology an excellent apology. It utterly fails to address the reasons given.

I want to add an update to my remarks in light of Update 1. I interpreted Rebecca Tuvel as responding to the letters quoted in the original post, but it was in fact responding to a different letter from Charles Hughes. While Hughes’ letter does mention anger and dismay, it provides substantive reasons and even textual quotations for argument. So, I think my point still stands.

That said, since I’ve been critical, I want to give due praise the further email quoted from by Tuvel in Update 1 which seems to me to be an attempt to address the substance of the criticisms in a helpful way. Especially its deliberate calling out of the need of expertise outside of philosophy.

This contrasts significantly with Eric Sampson’s response, which especially in the section on expertise is, frankly, condescending by somehow erasing the experts such as disability scholars who have raised these criticisms and instead presenting a picture of critics as essentially uncritical hangers-on, the equivalent to anti-vaxxers who have ‘done their own research.’

I also can’t see how it is an accurate representation of Singer’s views. Sampson heavily emphasizes that Singer’s position on infanticide only applies to very severe disabilities which are going to be exceptionally rare. Only the ones which create sufficient suffering that life would not be worth living. Sampson characterizes criticisms of Singer as taking narrow statements about *these* disabilities and generalizing them to all disabilities. Yet, in Practical Ethics, here is Singer on Down Syndrome – neither rare, nor, by his admission, incompatible with a life worth living:

“Prenatal diagnosis, followed by abortion in selected cases, is common practice in countries with liberal abortion laws and advanced medical techniques. I think this is as it should be. As the arguments of Chapter 6 indicate, I believe that abortion can be justified. Note, however, that neither haemophilia nor Down’s syndrome is so crippling as to make life not worth living, from the inner perspective of the person with the condition […]That a fetus is known to be disabled is widely accepted as a ground for abortion. Yet in discussing abortion, we saw that birth does not mark a morally significant dividing line. I cannot see how one could defend the view that fetuses may be ‘replaced’ before birth, but newborn infants may not be. Nor is there any other point, such as viability, that does a better job of dividing the fetus from the infant. Self-consciousness, which could provide a basis for holding that it is wrong to kill one being and replace it with another, is not to be found in either the fetus or the newborn infant. Neither the fetus nor the newborn infant is an individual capable of regarding itself as a distinct entity with a life of its own to lead, and it is only for newborn infants, or for still earlier stages of human life, that replaceability should be considered to be an ethically acceptable option.” (p. 164 – 165 of Practical Ethics, 3rd ed.)

This hardly seems to be the very narrow range of permissibility that Sampson makes out Singer’s position to be. Maybe he has revised his positions since Practical Ethics and has not made any adjustments to the 3rd edition in light of this. Sampson, as an expert, can surely enlighten about this. But I think the above quote makes clear that there is at least a historical basis for the kinds of criticisms levelled against Singer that is more substantive than Sampson makes out.

Fair enough, but keep in mind that Sampson is responding here not to disability scholarship on Singer, but the specific claims coming from those Rhodes faculty protesting Singer’s talk. Responding to these caricatures of Singer’s views, Sampson correctly notes that “Singer has never advocated for anything approaching the ‘genocide’, ‘extermination’, ‘slaughter’, ‘forced sterilization’, or ‘targeting’ of people with disabilities’” – all views (apparently) advanced by “Rhodes faculty members or students.”

Singer does offer a broad defense of infanticide, since he holds it is permissible to abort and kill even those fetuses and babies who would lead good lives. But, as you rightly note, this applies to all infants, not just disabled ones. Thus, those faculty claiming that Singer “targets disabled people” are mistaken. Indeed, at the policy level, Singer only ever ‘advocates’ letting parents decide whether to keep their newborn babies – disabled or not. This is further consistent with Singer’s point in the quote you cite; far from devaluing people with disabilities such as Down’s syndrome, Singer reminds us that “neither hemophilia nor Down’s syndrome is so crippling as to make life not worth living.” Again, Singer clearly states that “the principle of equal consideration of interests rejects any discounting of the interests of people on grounds of disability” (PE, 165).

“Singer has never advocated for anything approaching the ‘genocide’, ‘extermination’, ‘slaughter’, ‘forced sterilization’, or ‘targeting’ of people with disabilities’” – all views (apparently) advanced by “Rhodes faculty members or students.”

Ok, where? I don’t see that in any of the letters. Given that Sampson begins by characterizing “the first rule of responsible intellectual engagement and argumentation” as “if you’re going to criticize someone for the views they hold, you had better represent those views accurately” he seems to focus only on the criticisms that are the most extreme. By his account, even less extreme criticisms would be inaccurate, but he doesn’t engage with them, including several in the letters from faculty quoted in the Daily Nous article.

I’d also like to push back on your defense, because non-discrimination in certain respects, like the permissibility of infanticide, is hardly the whole story. Consider the following quotes (bolding mine)

“If we favour the total view rather than the prior existence view, then we

have to take account of the probability that when the death of a disabled

infant will lead to the birth of another infant with better prospects of a

happy life, the total amount of happiness will be greater if the disabled

infant is killed. The loss of happy life for the first infant is outweighed

by the gain of a happier life for the second. Therefore, if killing the

haemophiliac infant has no adverse effect on others, it would, according to the total view, be right to kill him.

The total view treats infants as replaceable, in much the same way

as it treats animals that are not self-aware as replaceable (as we saw in

Chapter 5). Many will think that the replaceability argument cannot be

applied to human infants. The direct killing of even the most hopelessly

disabled infant is still officially regarded as murder. How then could the

killing of infants with far less serious problems, like haemophilia, be

accepted? Yet on further reflection, the implications of the replaceability argument do not seem quite so bizarre. For there are disabled members of our species whom we now deal with exactly as the argument suggests we should. [Singer then goes on to defend the replaceability argument]” (PE 3rd ed, 163)

“Prenatal diagnosis, followed by abortion in selected cases, is common

practice in countries with liberal abortion laws and advanced medical

techniques. I think this is as it should be.” (PE 3rd ed, 164)

“I conclude, then, that a rejection of speciesism does not imply that all lives are of equal worth. While self-awareness, the capacity to think ahead and have hopes and aspirations for the future, the capacity for meaningful relations with others and so on are not relevant to the question of inflicting pain—since pain is pain, whatever other capacities, beyond the capacity to feel pain, the being may have—these capacities are relevant to the question of taking life. It is not arbitrary to hold that the life of a self-aware being, capable of abstract thought, of planning for the future, of complex acts of communication, and so on, is more valuable than the life of a being without these capacities. To see the difference between the issues of inflicting pain and taking life, consider how we would choose within our own species. If we had to choose to save the life of a normal human being or an intellectually disabled human being, we would probably choose to save the life of a normal human being” (Animal Liberation, 40th anniversary edition – not using a pdf so I don’t have a P# but it’s in the first Chapter)

Singer very clearly makes normative claims that DO discriminate between disabled and non-disabled lives. While he does not advocate for a policy of mandatory eugenics via prenatal selection or infanticide, it seems to me (correct me if I am wrong) that he thinks that the voluntary practice of this form of eugenics is, on the whole, the normatively correct path to take. In the Animal Liberation quote, he also talks quite literally about the worth, value and equality of lives.

I’m sure some critics do attribute views to Singer that he simply doesn’t hold and that his views are far from implying. I’ve seen enough of Twitter to expect that. But many of the criticisms mentioned in the letters quoted above, and that I have seem elsewhere, do not in fact seem to be so obviously false or ungrounded. Surely, if we are being intellectually responsible, those deserve careful consideration and treatment. Especially in light of the fact that they are coming from a marginalized group that has been subject to horrific violence on the basis of consequentialist reasoning.

As a Rhodes faculty member, I can tell you that Sampson is directly quoting from different faculty emails that flooded the listserv this past week. Some highlights: “‘Do those views disqualify Singer from participating in the exchange of ideas that ought to occur at a liberal arts college?’ My answer to this question is ‘yes’ — to the extent that he advocates for the killing of a particular group of people.This is not merely ‘controversial’, it is actually genocidal.” “I know how hurt I would feel if a speaker were invited to campus who advocated for eugenics for populations that I am a part of (e.g., queer, Jewish). While as an able-bodied person I cannot know exactly how my colleagues with disabilities feel, I have full trust in their descriptions of how hurtful this is and the kind of message it sends to them and our broader community.” “If Rhodes College is anywhere near serious about the values it allegedly, purportedly supports, the College should move quickly to create a venue where we can bring in speakers to make the point that killing disabled people is a murderous, uncivil idea, one that has no place in a civilized society, and is a position a shade more than ‘problematic.’” “Open advocacy of the killing of Jews or Blacks would be anathema, beyond the pale of civil, intellectual exchange. The open advocacy of murdering disabled people is merely ‘controversial’, and in no way should disqualify one from speaking at the College.” “There are plenty of Covid ethics experts out there who have not argued repeatedly and publicly for eugenics.” “If we want serious engagement with pandemic ethics, let’s find a speaker who can do that without the specter of eugenics. No one should be asked to defend their humanity as an intellectual exercise.” Sadly for the state of our college, Sampson is not the one guilty of exaggeration here.

This does seem exaggerated, but as far as I can tell (see my prior direct quotes from Singer), he does think that certain groups of people would, in an ideal world, be eliminated prenatally (or postnatally if prenatal detection is not feasible) and replaced with people with better hedonic prospects.

The quotes I gave in my previous post are consistent with support for non-coercive eugenics. This does not seem like an exaggeration at all. Several of these quotes focus on eugenics, so if you interpret Singer differently than I do in my above post, maybe you can explain why you think it is a misinterpretation to understand his endorsement of prenatal selection using abortion for disabilities like Down syndrome is not eugenics.

It’s hard to tell how exaggerated this is, since it’s unclear if the author attributes to Singer the view that killing disabled people, in the technical sense of moral persons that philosophers like Singer use it, is permissible or if they are responding to Singer’s view that killing disabled infants is permissible. In the latter case, I don’t see the exaggeration. If we’re going to be hyper-literal, careful readers of Singer in this dispute, let’s be hyper-literal, careful readers of critics as well.

This one does seem exaggerated, since Singer probably can’t be accurately characterized as openly advocating for murdering disabled people, even infants.

I don’t know enough about Singer’s public speaking to judge this one, but as far as I can tell, he is on board with a form of eugenics.

Attributing to Singer a specter of eugenics hardly seems an exaggeration. The second sentence depends substantially on what characterizes a person’s humanity.

I appreciate the insight into the sorts of exchanges Sampson is responding to. His presentation of Singer’s views, and characterization of the criticisms, still doesn’t seem like a fully accurate representation.

If this counts as charity, we need to name a new fallacy after it. First, there’s an enormous difference between Singer’s suggestion that a world with more hedons would be a better world and these individuals’ repeated claims that Singer advocates for the killing or even murder of a particular group of people (yes, the terms here matter enormously). Second, the faculty member comparing Singer’s liberal eugenics to the Nazi eugenicist programs to wipe out queers and Jews elides a critical distinction between two wildly different senses of the term ‘eugenics’ (not to mention the insult to Singer, himself a Jew). In a recent piece, Singer et al suggest it might be prudent to opt for a different term than ‘eugenics’, given the latter’s “association with forced sterilization programs in the US and Nazi Germany, as well as the Nazi program of euthanizing disabled people, and the mass murder and attempted genocide of Jews and Roma during WW2…. While contemporary bioethicists disagree about whether the state should play a role in helping parents discharge their procreative obligations, none think the state should engage in the mass sterilization or murder of their own citizens. In other words, the rejection of Nazi-style eugenics programs is unanimous” (Monash Bioethics Review, 2021)

Finally, to the quote about Singer’s “open advocacy of murdering disabled people”: I’m glad you acknowledge this one “seems exaggerated” and that Singer “probably can’t be accurately characterized as openly advocating for murdering disabled people…” (!) What an extraordinarily weak defense of Singer in response to such an outrageous misrepresentation of his position.

We regularly teach Plato, who specifically argued for infanticide for and discussion of these beliefs is often fruitful for students who almost always reject Ps view (as well as his authoritarianism) But after reading They know why they hold the view they hold are are not just mindlessly paroting what were were taught as childen (This applies even more so the critique democacy, as Plato’s arguments are in my view the best anti-dem and being able to discuss and,for most of us, reject such arguments ( Should be ban Plato? ) Should Arisotle be purged frorm the academy b/c of his defense of slavey, or Schopenhauer because of his hyper misogyny That a so called liberal arts college would engage is such rampant anti-intellectualism s involves a deep mistake regarding the goal of liberal arts and philosophy in particular. We teach in order to challenge sudents to think for themselves, to consider arguments and counter arguments–and think for themselves instead of parotingn what their parents, church, peer group, Ayn Rand or whatever. It is a cliche that the solution to bad speech is more speech, and I remember distinctly when the Klan came to Eastern Iowa there would be 20-50 hooded racists and much greater number of counter demonstrators.

I am not saying I agree or diagree with Singer, I actually am sympathetic to his views on effective altruism (though with reservations), On euthanasia of the seriously disabled infants, I doubt he is right–way to broad a category of disabled–eve once down’s syndrome (!!!)(I hope he changed his mind on this) But I don’t think I am a genocidal maniac*if* a baby is born with only a spinal collumn, or if there is extremely good medical reason for thinking the child would live a very short and painful existecce,So these are rational issues to discuss.

FWIW I am sympathetic the disability rights–Esp with regard to many people on the autistic spectrum who, despite what family or even friends might want do not want to be”cured”[ not dissing other aspects of DR movementI am just most familiar with the strugglea of people on “the spectrum” But this is a debate we should have, It helps neither the cause of truth or morality to sweep arguments under the rug, even when they violate a very well cherished ethical (not so sure that Tukla should emphasize ‘trusting experts too much [in philosophy, not science] Focus should always be on the arguments

Just to emphasize a point I posted about earlier elsewhere in this discussion, and which I think some people may be missing: when you suggest that you hope Singer has changed his view with respect to infants with Down’s syndrome but not with respect to infants with other features, I think you need to be a bit clearer about what you want him to change his view to.

As I understand it, his view about both of these cases is the same because his view about all infants, including ones that we would typically label as not at all disabled, is that they may be permissibly killed if the parents (or other interested adults) wish it, if nobody wants to adopt the infant, and (if we adopt what he dubs the “total” view) if we replace the infant. There is no special category he applies just to (e.g.) “disabled” infants or anything like this, at least as far as I read him.

So when you ask him to change his view about some infants but you’re happy with his view about others, you’re asking Singer to rather radically rethink things by carving out a special category of infants who are badly off in certain ways and who it is permissible to kill, and a larger category of infants who it is not permissible to kill. But he does not think we can do this without, among other things, trampling on abortion rights, since he doesn’t think there are morally salient features that infants have and that fetuses lack.

And notice Singer would perhaps suggest that his existing view creates much less of a hierarchy between e.g. disabled and non-disabled infants than the one you are suggesting. So we might worry that the change you are proposing, at least in Singer’s eyes, is going to make things worse for humans with certain disabilities, rather than better, because now they and they alone are liable to be permissibly killed as infants, compared to the rest of the humans (including those with Down’s syndrome) who are not.

I may be misreading you by understanding your claims about permissibility. It is possible you are suggesting that killing some infants is mandatory, and that Singer correctly notes this in the case of infants born with only a spine, but incorrectly includes the Down’s syndrome infants in this category. If that is your suggestion, then you are misreading Singer, who I think has been rather clear that it would never be mandatory to kill an infant with Down’s syndrome any more than it would be mandatory to kill any other infant.

(Again, disclaimer: I end up on the opposite side of what I take to be Singer’s view. So I am not endorsing anything. But I think we want to be clear about what his view is!)

Just speakng in the first person, if I was to be alive for say, five months and in constant agony, I would literally be better off dead.this is an uncommon and very extreme type of case, but as Thomson says about Abortion, there are cases and there are cases…

When I ran over a squirell, I felt bad, but I did not think I committed murder. Of course we all want (I hope) the least harm possible, but sometimes (rarely) infantile euthanasia is justifable for this reason–my only concern is that people would reach out for this sort of extreme case and expand it. via invalid slippery slope arguments. I think I am taking a more or less moderate positoin, one that prima facie is opposed to involuntary infantile euthanasia but recognizes there are extreme cases(suppose you were the parent of a constantly suffering child of the sort I mentioned would you consider it obviously immoral to end such a life. Obviously it could be immoral–But would it not be better for you to discuss and argue the issue with me than for you to shut me out of the debate so that I go on being a martyr for free speech and, assuming your view is correct, go on believing false things. if we want our beliefs to be rational we must allow them to be challenged.. Yes I am a big fan of J.S. Mill–the arguments in on liberty are not deep, but they are important and once you think about them (or once think about them) common sense. Historically moral progress has occurred when we Stopped the gag rule on slavery, stopped ignoring or trivializing feminist voices.. that isx when we engage in critical intelligent debate. i don’t have a strong view one way or the other on euthanasia (except the point about downs syndrome and, i fear some people lump autistic people into the same group of undesirables… but these are conscious beings ( I think value only obtains with respect to conscious states, and some conscious states are very bad indeed) Maybe I am wrong.. come at me, give me an argument [ I am probably more likely to be wrong than others as I am not a medical ethicist and have not thought these issues through as much as others. Again, those of you who have thought it through more, give me your reasoning. The idea that we should accept beliefs just on faith without allowing for criticism is the way of the authoritarian, not the free liberal democrat. Then again, maybe liberal democracy is a sucky government form–again, give the argument. Really to deny this is to deny the value of philosophy, to be what Socrates calls in the Meno a mysologic person. that sort of view is just darkness to me… a depth of intellectual feebility that, alas is quite common ( I don’t mean primarily philosophers) But as educators we want to help students get out of it and think for themselves (do I contradict myself, very well, I guess I do, I think one problem with moral philosophjy is that there are lots of views are plausible… but when taken to extremes they are….. well that is how we get counterexamples!

So, OF course I would agree that a Nazi prof who uses her ethics class to endorse the final solution ought to be fired.. but this is an extreme case–it goes against my general principles, but general principles, in my view, are either vacuous or allow for exceptions.

how is this different from recognizing that running over a squirell, a conscious being who suffers as the car bears down over him/her, is idfferent from running over a one year old? we all recognize gradations of value. I also want to take back what I said about universal ethical principles being vacuous if they admit no acception–I think something like Kantian respect for the value of an individual may apply univerally, though I would not apply it as Kant did (if my child was suffering grievously and about to die anyway, I think I AM respecting her by killing her (Rachels is spot on about the distinction between killing and letting die)

I am not sure if this is directed at me (reply threading has gotten wonky), but I just want to say that I have not suggested, and would not suggest, eliminating Plato, Aristotle or even Singer from the curriculum. Teaching about a philosopher (especially historical ones) is an entirely different context from giving a living philosopher an invitation to give a talk. And, as remarked in another comment, I am not sure whether ultimately disinviting Singer would be the correct thing to do in this case.

but you assume you are RIGHT.. as if you you had authoritarian control over truth. ANd that is almost always a bad thing. But let me know defend Singer, not on euthanasia, which I hope I have indicated I don’t really aggree with, but on effective altruism and animal rights. I am a poor sinner. But after reading Singer “Famine, Afluence and morality” I definitely gave more to help out those that are suffering than I did before. Also, I am a poor sinner in that I eat meat. But I now eat meat when i get a strange craving.. maybe once a week, and definitely try to avoid factory farming. Both of these ethical positions are entirely salturary and helpful. I don’t get why people focus just on the euthanasia case and ignore his other wonderfullly beneficient views.. IS it specisism?

Isn’t it clear that the beneficial effects of Singer;s views on poverty and animal welfare have had a huge positive impact, whereas his euthasasia views are quibbles amongst philosophrs (mostly)

And I still have not heard an argument against EVERY case of infantile euthanasia–I think Singer’s problem is that instead of focusing entirely on the welfare of the child (as I said some people alas are better off dead).. A good thought experiment would be this. Suppose you had a child with an incredibly painful ailment and no real hope for recovery. IN the afterlife, would that chlid thank you? I think s/he would I(I would!!!) If not then I am wrong .. again these are issues to be debated, not trivialized or demonzied./ Singer’s problem is that he includes (i think) not just the welfare of the child, but the convenience of the parents and society (hope I am wrong here.. but that is how it sseems) I think that is wrong. BUt it is still a position that is open to rational discussion. anti-rationalism is the road to tyrany.. LOOK AT HISTORY sorry, i was emoting there. but i treally believe in reason, construed broadly to include phenomenology and the cognitive aspects of our emotions. .I don’t think we have any other grounds for thinking anything is right or wrong or true or false.

I am sorry if I am parodying the view, but it is as if babies without brains have more value on your view than pigs with quite sophisticated ones. I don’t see this having any philosophical justification, though some relligious traditions may insist on it.. I say this as as a theist, albeit perhaps an unconventional one. If there is a God of love that love permeates all creation, not just us poor idiotic humans.,

I might well be digging in my heels and being too charitable, but:

(1) You think the the most apt summary of Singer in the context of this discussion is that he suggests “that a world with more hedons would be a better world.”

This is, apparently, the summary you give as a model of accuracy in contrast to critics’ characterizations. This despite the fact that Singer has publicly argued in the NYT that disabled people might reasonably be denied life-saving medical care in cases of rationing, and has argued in favor of the practice of using prenatal testing and abortion to eliminate disabilities such as Down syndrome in a Practical Ethics – along with the extension of such practices to infanticide.

(2) Your interpretation of this quote:

“I know how hurt I would feel if a speaker were invited to campus who advocated for eugenics for populations that I am a part of (e.g., queer, Jewish). While as an able-bodied person I cannot know exactly how my colleagues with disabilities feel, I have full trust in their descriptions of how hurtful this is and the kind of message it sends to them and our broader community.”

is that it is “comparing Singer’s liberal eugenics to the Nazi eugenicist programs to wipe out queers and Jews” despite not once mentioning Nazis or coercion. You then go on to mark only the distinction between coercive eugenics and non-coercive eugenics, as if the ONLY reason the person quoted might feel angry or hurt at someone advocating eugenics for queer or Jewish people is if those eugenics were coercive.

We are not going to be able to have a productive discussion. You insist on the most extreme possible interpretation of critics, even when less extreme interpretations are readily available (do you really not think it would be disturbing if Singer argued the same things about queer or Jewish people as people with Down syndrome?). You also insist on vacating Singer’s positions of any action guiding force, despite direct quotes I’ve provided showing that he normatively endorses certain actions, actions that involve killing (in the case of infanticide) and letting die (in the case of medical rationing).

You incorrectly describe Singer as “in favor of using the practice of prenatal testing and abortion to eliminate disabilities such as Down syndrome.” He never says we ought to “eliminate” such disabilities; he only ever defends allowing parents the right to choose how to proceed following prenatal diagnosis. Directly from the horse’s mouth from an interview at inside higher ed this week on the controversy at Rhodes (my emphasis): “Clearly, these faculty have not thought very deeply about these questions. They say that they object to my advocacy of allowing parents to choose euthanasia for severely disabled newborn infants (as they may do in the Netherlands, for example, in accordance with the Groningen Protocol). They say that this is ‘eugenicist’ and ‘denies the very humanity of people with disabilities.’ I challenge these faculty to explain to their students and the wider public their position on abortion following prenatal diagnosis that indicates a serious disability, or on allowing parents to choose to withdraw life-support from severely disabled infants in neonatal intensive care units, knowing that the infants will then die.”

I agree with several others’ assessments of Singer’s views on these matters. As Daivd Weltman, states, “There is no special category he applies just to (e.g.) “disabled” infants or anything like this…If that is your suggestion, then you are misreading Singer, who I think has been rather clear that it would never be mandatory to kill an infant with Down’s syndrome any more than it would be mandatory to kill any other infant.”

And from Alastair Norcross: “There would have been more net goodness in the world if, instead of me, my parents had had a different child who was a bit more conscientious, a bit less selfish, more good looking, with more hair, and better eyesight. None of that entails that hedonistic maximizing utilitarianism endorses the murder of me, or of anyone else who could be or have been replaced by someone who would contribute more to net utility. Judgments about total value don’t translate simply and directly into judgments about what kinds of actions to endorse. To think they do is to take a ridiculously simplistic, but distressingly common amongst supposedly smart philosophers, approach to utilitarianism. Any cursory acquaintance with the world in which utilitarian judgments are to be made is sufficient to show that these criticisms of the theory are complete straw men.”

With his growing shift in favor of hedonistic utilitarianism, I wonder if Singer still maintains that “the life of a self-aware being, capable of abstract thought, of planning for the future, of complex acts of communication, and so on, is more valuable than the life of a being without these capacities.” If an individual’s life has more pleasure than pain, a hedonist should not care whether one has these further cognitive capacities or not.

Further relevant is the slippage between the everyday concept of disability versus disease. A disability does not automatically imply that one’s life contains vastly more pain than pleasure; for this reason, it is wrong to discriminate based on disability alone. But certain diseases cause pain so excruciating and unbearable that many people prefer not to go on living, hence Singer’s defense of euthanasia.

It’s true that Singer thinks parents should be able to abort or kill a newborn for seemingly any reason. Since no newborn has personhood, infanticide does not wrong the newborn, although it may have damaging effects on the parents, the medical profession, and society at large – effects that weigh against infanticide. But insofar as there is no morally bright line between the moral status of a newborn and that of a very late term fetus, it is in principle allowable. Still, while Singer has argued that infanticide is permissible, I wonder if he would defend the practical permissibility of infanticide – given all the negative consequences that could result from mainstreaming the practice (including how horrified people would be). Here it’s interesting to note that far from being an idea too horrifying to even consider, however, infanticide was commonly practiced across a variety of cultures throughout history.

“With his growing shift in favor of hedonistic utilitarianism, I wonder if Singer still maintains that “the life of a self-aware being, capable of abstract thought, of planning for the future, of complex acts of communication, and so on, is more valuable than the life of a being without these capacities.” If an individual’s life has more pleasure than pain, a hedonist should not care whether one has these further cognitive capacities or not.”

That may well be, but I think the quoted passage from an special anniversary edition of Animal Liberation released 6 years ago is sufficient basis to make it not unreasonable to interpret Singer as having a view that there is a hierarchy of lives, which was one of the criticisms levelled.

As to the rest, it’s not really infanticide that’s the issue. You haven’t addressed at all the quotes that I gave, which seem to me at least to show that Singer thinks it would be better, all things considered, for disabled fetuses/infants to be replaced with nondisabled ones. It’s not just a question of meeting the threshold of having a life worth living, for Singer there are evaluations beyond that threshold about more or less worth living based on expected wellbeing.

Hence, for example, his suggestion that healthcare be reasonably rationed on the basis of disability (using QALYs) in the 2009 NYT article that Charles Hughes links:

“Health care does more than save lives: it also reduces pain and suffering. How can we compare saving a person’s life with, say, making it possible for someone who was confined to bed to return to an active life? We can elicit people’s values on that too. One common method is to describe medical conditions to people — let’s say being a quadriplegic — and tell them that they can choose between 10 years in that condition or some smaller number of years without it. If most would prefer, say, 10 years as a quadriplegic to 4 years of nondisabled life, but would choose 6 years of nondisabled life over 10 with quadriplegia, but have difficulty deciding between 5 years of nondisabled life or 10 years with quadriplegia, then they are, in effect, assessing life with quadriplegia as half as good as nondisabled life. (These are hypothetical figures, chosen to keep the math simple, and not based on any actual surveys.) If that judgment represents a rough average across the population, we might conclude that restoring to nondisabled life two people who would otherwise be quadriplegics is equivalent in value to saving the life of one person, provided the life expectancies of all involved are similar.”

He considers a literal objection that this discriminates against disabled people, but provides arguments against the suggestion that QALYs should be based on disabled people’s judgments about quality of life with their disability. He concludes by endorsing QALYs as “the worst option except for all the others.”

Thank you for the Singer quotation on QALYs. But should this quotation (and others like it) really put Singer beyond the pale of polite company, unworthy of being hosted for a college lecture?

The quotation raises an important issue, and stakes out a position on this difficult terrain. Singer does not propose this position gleefully. Instead, he seems to recognize that it appears ghastly, and he recommends it as the least bad among a menu of bad options. (It’s “the worst option except for all of the others.”)

“Thank you for the Singer quotation on QALYs. But should this quotation (and others like it) really put Singer beyond the pale of polite company, unworthy of being hosted for a college lecture?”

I haven’t weighed in much on the prospect of the disinvitation itself for two reasons. One is that I think there is worthwhile criticism of the dismissive responses some have made about the substance of the criticisms themselves. Even if a principled stance on academic freedom settles the disinvitation question, it doesn’t justify dismissiveness about the underlying criticism. The other is that I feel torn in a lot of different directions. I’m honestly not quite sure what I think.

On the one hand, I can appreciate the importance of fairly hardline stances on freedom of speech and academic freedom. There is a lot of room for abuse when it comes to censorship, and historical precedent that shows we ought to fear that even if it seems like any given instance looks reasonable and beyond the pale.

On the other hand, there is also a lot of historical precedent that shows the dangers of positions like those Singer takes (positions that, cards on the table, I think are false). Singer’s influence is actually very much a reason to take those especially seriously (in contrast to some folks who think it more or less guarantees him a seat at the table). I think ‘But at least his heart is in the right place/he’s not very strident about these stances’ has about as much weight here as it does justifying imposing restrictions on speech that seem well motivated and intended to be implemented carefully. Sure, in the ideal realm of imagination it’s all fine, but how is it going to play out in the messy real world?

Furthermore, it’s not clear to me the precise scope of academic freedom should be here. Surely a community has a right to make decisions about who they want to come and give special talks, and not inviting someone or disinviting someone to speak seems like it is consistent with that right. Surely Howard University is under no obligation to invite Charles Murray to speak there. If somehow through a fluke Charles Murray was invited to speak at Howard University, it seems strange to then insist that academic freedom requires that he not be disinvited in the spirit of open discourse. Not giving someone special invitations to give talks does not seem equivalent to me to censorship or other more significant restrictions on speech or academic activity.

I should note that you asked two questions, so to address the other one: I’ll say I don’t think Singer himself is ‘beyond the pale of polite company.’ My standards for ‘who might reasonably be shunned in day-to-day society’ are certainly much more stringent than my standards for ‘who might reasonably be excluded from being given special platforms for expressing their views on certain issues.’

Again how we define ‘disabled’ matters tremendously. Singer does not think just any manner of being ‘disabled’ negatively impacts well-being – e.g., compare 1) a condition so severe that the baby lives for weeks in utter agony before succumbing to their ailment, to 2) a ‘disability’ like Down Syndrome, knowing full well that many people with Down Syndrome lead lives filled with more joy and happiness than those without it. While Singer thinks it’s permissible to commit infanticide in a broad range of cases for disabled and non-disabled newborns, he only thinks it’s obligatory when a life will contain so much pain and suffering that it would be worse than death.

Very juicy post. You carved up Singer really nicely.

(Disclaimer: I’m basically on the anti-Singer side in this debate, although the non-philosophers on my side do us few favors when they present Singer’s views uncharitably [this doesn’t include you, David!], and I don’t think the proper response is to protest against his talks on unrelated issues.)

I am not a Singer expert, so it’s possible he’s written stuff on this I’m unaware of. But in fact his view is even more permissive of infant killing than you are suggesting, David. Any infants may be permissibly killed, so long as the parents don’t mind and so long as there’s nobody who wants to adopt the infant (and so long as they replace the infant, if we adopt what Singer calls the “total view”). (See pages 151-4 of Practical Ethics 3rd ed.)

He thinks that practically speaking this question will typically arise only in cases of severe disabilities, since other parents don’t want to kill their infants. Thus he includes a special discussion of disabled infants later in the book, but as far as I can tell there is nothing special about them ethically, as far as Singer is concerned. Presumably the only reason he singles them out for discussion is that this is a live topic of debate (whereas killing other infants is not), and the book is called Practical Ethics.

Shall we establish committees of dehumanizing and harmful ideas to adjudicate what ideas are dehumanizing and harmful, and therefore can’t be defended? If not, who or what is supposed to adjudicate this?

“Who or what is supposed to adjudicate this?

We are supposed to adjudicate this, together. If I call some idea dehumanizing or harmful, that doesn’t mean that I think that some committee ought to rule out defending it from on high. It simply means that I don’t think you should defend it. It’s part of a healthy culture of deliberation that no evaluation of the ideas of others is considered off limits. Free deliberation will involve working through the question of whether certain ideas are dehumanizing or harmful as well as whether they are incorrect.

Frankly, a conversation where each person is too afraid to say that a certain idea is dehumanizing or harmful for fear of being called intolerant seems far more stultifying to me than the conversation that currently exists, flawed as it may be.

You make it sound as if it’s the people who are trying to stop Singer from speaking who are the real victims here, because others criticism them for being intolerant. Well, who is trying to silence whom? Who is creating the hostile atmosphere for whom? No one is silencing Singer’s critics, so far as I know. They can have an entire conference on why Singer’s views are harmful and dehumanizing and I doubt any of the people defending Singer here would care.

Sure, each of us can decide what ideas are harmful, dehumanizing and bad in other ways. But each of us can’t decide what viewpoints everyone else is allowed to listen to in virtue of that fallible judgment.

I didn’t say that anyone was a victim in this situation. I actually didn’t refer to the situation with Singer at all. I was just responding to your remark which implied that criticizing an idea as dehumanizing or harmful in public means that you are committed to setting up some sort of “committee” with the prerogative to decide which ideas are too harmful to be defended. I wanted to point out that criticizing an idea as harmful or dehumanizing does not mean that I think my judgment to that effect should be enforced by some authoritarian committee, anymore than your judgment that my speech is intolerant commits you to thinking that my speech should be forbidden by committee.

But since you brought Singer’s situation up, nobody is silencing anyone in that situation. Publicly criticizing Singer’s views and calling for Singer to be disinvited does not “silence” him, nor is it an attempt to “decide what viewpoints everyone else is allowed to listen to.” If the critics of Singer were attempting to use force to prevent the philosophy department from inviting Singer or to attempt to prevent Singer from speaking, that would be a problem. But they are not doing that. They are trying to give reasons to the philosophy department and the community at large for why the philosophy department should not come have him speak. That is not “silencing.” It is a form of public advocacy.

If Singer is disinvited, will he have been “silenced?” Well, there are plenty of people that the philosophy department at Rhodes did not invite to give a talk in the first place. Are they “silenced” because they are not able to give the talk? If not, then Singer won’t be silenced if disinvited either.

To be clear, my own view is that Singer should not be disinvited. But I don’t think imputing authoritarianism to the people who argue that he should be is fair or correct (though there are likely some people with authoritarian attitudes who think Singer should be disinvited, just as there are likely some people with authoritarian attitudes who think that he shouldn’t be).

You might disagree with what those who think that Singer should be disinvited say about the value of Singer’s work or what they say about whether disinvitation is an appropriate response, but they are not compromising any important freedoms in doing what they do. And when you criticize these other people as intolerant, you do not compromise their important freedoms. As I said, nobody here is a victim.

You express worries about a stultifying atmosphere in which people are afraid to call ideas “dehumanizing” and the like. It seems a weird complaint to make in light of the fact that it’s the people who call Singer’s views such things who are trying to prevent him from speaking. The only stultifying atmosphere relevant to this conversation is the one that people on that side are creating. And, colloquially, preventing someone from speaking in this way is “silencing” that person.

As far as the “nobody’s freedoms are being violated” point: see my second reply to Derek below about culture versus rights. Maybe nobody’s libertarian rights are being infringed, but that isn’t everything we care about.

I find this very funny. When it comes to “cancel culture” some speak as if the standard for “force” that is of moral concern is at a very high bar: threats of violence or violations of constitutional rights. But then at the same time, pervasive subtle power structures are really worrisome when it comes to racism and sexism. Now I think it makes sense to talk about social pressures as a kind of “force” that can be morally concerning, and when I do, I’m actually agreeing with the people who express worries about subtle forms of racism that might be pernicious even if they don’t manifest in violence.

What we’re looking at here is not just others speaking their minds about Singer’s work, but a concerted effort to pressure the department to disinvite him. And surely worries about making enemies with faculty members in other departments can be a substantial pressure. This could certainly come up later in situations in which funding is at stake. And how would you feel to be a student in one of those departments petitioning against Singer if you were privately sympathetic with his views?

Regarding your first paragraph: I’m not saying such a stultifying atmosphere currently exists. I am saying it would exist if we listened to you about what kinds of debate we should listen to. I think a world where people refrain from “calling out” speakers in roughly the manner that people have called out Singer today would be a worse one on roughly (John Stuart) Millian grounds. That is, it enriches everyone intellectually and morally when many different opinions are given voice in the public arena. If people followed your recommendations and refrained from calling out Singer, we would lose out on these benefits. Of course, this argument would fail if the calling out violated anybody’s rights or was “bad speech” that didn’t contribute anything of value. But I disagree with both of these ideas.

You say that people are trying to prevent Singer from speaking. They are asking the philosophy department not to have him over for a talk. This is just not preventing him from speaking in general. He still has all sorts of avenues for speech and all sorts of audiences. If the goal were to prevent his ideas from being heard by others, then calling him out in this way would be very counterproductive because of the attention that ultimately draws to him and his ideas. For these reasons, I don’t think that Singer is being prevented from speaking or being denied an audience in any sense.

I read your response to Derek Baker below. I pretty much agree with what you say there in that I don’t think that anybody’s rights have been violated, and that the primary issue here is what kind of culture we want to live in. (Though I want to note that your comments “committee of dehumanizing and harmful ideas” are surprising to me in light of the position you take in that comment. It seems like attributing to others the view that a legal structure for forbidding certain kinds of speech ought to be set up is at odds with the view that the main dispute here is not about formal legal structures but about extralegal social/cultural norms.)

I think where I differ with you is that I think that calling out Singer is a positive contribution for the roughly Millian reasons I mentioned earlier; that it adds to the diversity of opinions in the public sphere, which educates and enriches everybody. You worry that this kind of speech has various negative consequences, such as making students and others who might be privately sympathetic to Singer’s views feel worried about making enemies in the department. I agree that these are genuine negative consequences of the speech that those calling out Singer engage in, but I disagree that these consequences are by themselves reason to refrain from engaging in that speech. Part of having a healthy culture of free expression means recognizing and dealing with the problems that free expression causes without compromising on that expression at all. When publicly voicing strong opinions about ethically charged matters creates problems, we should not jump to the conclusion that people ought not to speak but rather try to think of some other solution. Presumably there are ways for members of the relevant department members at Rhodes to make a public commitment that they will treat members of the university who disagree with them on the Singer issue fairly. Maybe there isn’t a good solution like this or the solution is unlikely to be implemented — I am not familiar enough with the details of the situation at Rhodes to know. Regardless, having a commitment to a culture of free expression means accepting the negative consequences of free speech even when it is difficult to completely ameliorate them.

The reasons given are gross (and given that the writers are allegedly scholars, likely willful) misrepresentatations of Singer’s views. I”d say Tuvel is being far too generous in granting these calls any legitimacy.

“The creation of a hierarchy of lives… is a logic that has a long and violent history.”

So I assume all the members of the faculty in the Rhodes College Department of Anthropology and Sociology and the Africana Studies are Vegan? Otherwise that would be rich coming from them in the context of trying to condemn Singer.

I get the sense that these criticisms of Singer are vague and amorphous. Does he actually come out and say the sorts of things these objectors are mentioning, or is it all a bit of broken telephone? It’s unfortunate to see that they don’t provide any kinds of references to passages or talks by Singer.

I really wish they’d specify what it was that they were reacting to. I’ve read and taught Singers material for years, and the only thing that sounds close to what they’re talking about is the concept of hierarchical biocentrism. That being said, one can easily be a higher or biocentrist without advocating against people with disabilities.

Singer is not even a biocentrist. He advocates for *equal* consideration for the interests of sentient beings (not lifeforms in general).

I hardly see how that would be compatible with the idea of hierarchizing human lives, which he is accused of (he simply says some life might not even be worth living, stressing on extreme cases, a point which seems self-evidently true).

Rebecca Tuvel has, once again, shown that she is a phenomenal voice for academic philosophy and defender of the values of open engagement and discourse which are central to what allows universities to function in their appropriate capacity.

Even if you don’t agree with Singer or find his views disturbing, how can anyone with a PhD in philosophy, never mind a faculty member at a university, think it is appropriate to try to get an event with him cancelled or to remove him from a panel?

Ronald Dworkin famously said that that “morally responsible people insist on making up their own minds about what is good or bad in life or in politics, or what is true or false in matters of justice and faith. Government insults its citizens, and denies their moral responsibility, when it decrees that they cannot be trusted to hear opinions that might persuade them to dangerous or offensive convictions. We retain our dignity, as individuals, only by insisting that no one — no official and no majority — has the right to withhold an opinion from us on the ground that we are not fit to hear and consider it.” Calls to cancel Singer’s talk are infantilizing of students at Rhodes. Good on the philosophy department for holding the line in the face of enormous pressure.

Posted without comment. Currently located in the “Heap of Links” at Daily Nous.

From the linked article: ““cancel culture.” This is the alleged tendency of online “mobs” to attack some target for their ideological impurity, often resulting in the target losing their job (hence being “cancelled”).”

The article is framed explicitly as a response to a frustratingly poorly argued piece in the Atlantic, which itself is focused on the alleged scourge of faculty firings.

I think Singer’s job is safe.

Quibble about one’s frustration (or not) over the poorly argued article if you’d like. Either way, this situation presents a clear case of a group of people (read: mob) calling for the revocation of a professional function for an individual on the basis of his views. And the thing is, most of us can’t count on being Singer, nor do we have his job security. So call it whatever you like, it is instructive to compare such downplaying of “cancel culture” with occurrences like this.

Part of the point of the linked article is that there have always been problems with institutions finding ways of suppressing viewpoints they don’t like. This isn’t good, and we should object to it when it happens. But the “cancel culture” narrative relies on the idea that things have gotten worse. My own view is that this is obviously not true of the culture at large–a much larger range of views gets published now than in the past. Maybe it is true specifically within academia, but I’m skeptical. In any case, Singer seems like a particularly bad figure to point to in making the case that things have gotten worse, given that he has been a target of these kinds of protests and complaints for decades.

I’d also say that while in general revoking an invitation to a professional event on the basis of one’s views is bad, things get more complicated when one’s profession is the sharing of said views. It isn’t like his views are irrelevant to his professional contributions.

Also, just to ward off uncharitable readings, when I say “complicated” I mean complicated–as in it is hard to say what academic freedom requires in a lot of these cases. I will add that in this particular case, asking the college to cancel the talk after the department refused is out of line and should be criticized.

Hi Derek. As I see it, cancel culture isn’t only (or even primarily) an institutional problem — that’s part of why it’s called a culture. As to whether your view is right, and your avowed skepticism, I invite you to look over the essays linked here:

https://heterodoxacademy.org/?s=the+skeptics+are+wrong

https://heterodoxacademy.org/blog/student-hostility-free-expression-behaviors-surveys/

Yeah, I guess I don’t really think that the cultural stuff is that important, and that free speech and academic freedom are pretty much institutional values. The big problem is that I can’t figure out what the people concerned about culture want. It sounds like these blog posts want more open expression, and also want more civility. But civility and open expression conflict with each other. Debating in a civil manner often requires a lot of self-censorship. Maybe we need more self-censorship on hot button topics, but the blog posts seem to regard that as bad too.

They complain that students now put a higher value on classrooms that make them feel comfortable. But they also complain that students feel like they’re walking on eggshells. But isn’t the latter a complaint that students don’t feel comfortable? How do we solve the problem, other than asking some of these supposed SJWs to stop expressing some of their opinions about how others are wrong?

I mean, some of this stuff points to potential problems. But some of it is just silly: “During my first days at Smith, I witnessed countless conversations that consisted of one person telling the other that their opinion was wrong. The word “offensive” was almost always included in the reasoning.”

Part of free speech is you are allowed to tell another person that their opinion is wrong, and you are allowed to include the word “offensive” in your reasoning.

Hi Derek — thanks for the thoughtful reply. As I see it, you’re hitting on some of the salient issues: how do we balance freedom of expression with civility; how do we balance the comfort of the people wielding institutional force in order to pursue political goals, with people who are made to feel that they must walk on eggshells as a result?

I’ve looked at some of the data in detail, and if it’s correct that political polarization has been growing since the 1990s, in part fueled by the rising partisanship in humanities education, then I think the majority of us who are actually in the middle on most issues owe it to one another to try to drown out the extremists by speaking to those who are also in the middle, but are on the other side of the divide on certain issues. That is, we owe it to one another to model the kinds of ameliorative conversation that helps the sensible people in the middle avoid the fanaticism of the extremists.

https://www.philosophersinamerica.com/2020/06/23/education-as-a-public-resource-for-addressing-american-political-polarization/

Hi Derek,

I disagree with you in that I think the problem has notably gotten worse in the last decade. But suppose for the sake of argument that I concede the point. How much difference would that make? On the issue of police brutality, many conservatives have made the point that there’s a lot less of it now than there was in the past, the 1970s for example. That helps to contextualize some of the concern about this, but it only goes so far. A reasonable person could definitely think police brutality is a major problem today even though it used to be a much worse problem. So the same point I think applies here: how much people were “cancelled” or quasi-cancelled in the past doesn’t seem like the most fundamental issue. Giving new attention to a longstanding issue is often worth doing, and maybe the recent concerns about “cancel culture” are an example of this.

Hi Spencer, I don’t disagree with the normative point. I said that even if things aren’t getting worse we should still criticize violations. But I think getting clear on whether things are getting worse or not is important for two reasons. First, I think it is important to try to assess to what extent the complaints about cancel culture are really complaints about less free speech, versus the fact that we have a much greater range of voices with access to mass media than ever before, and so arguments and criticism are getting much more extreme than lots of people are used to. I think some of the complaints about cancel culture are real. But a lot of them honestly strike me as elite centrist pundits getting pissed that the audience can now make fun of their articles on Twitter and mistaking their wounded pride for a commitment to free speech. I worry that what some of these figures really want when they talk about free speech is a return to the good old days in which the range of opinions that could get access to a mass audience was much more limited, and so they could count on the criticism of their views always being moderate and polite.

The second reason why it is important just has to do with the specific point that the linked article was making, that these comparisons of what is going on now with the Cultural Revolution or Puritan suppression of rival religious views are unwarranted, given the evidence presented so far. I’ve seen several people, including relatively famous writers, suggest on Twitter that this could lead to a new form of totalitarianism. So putting things in perspective seems important.

Yeah it’s relevant to the direction we’re headed, that much is true. I don’t think what’s happening with Singer here is anything like the worst kind of case. Singer is going to have an audience even if he can’t give this particular talk. Same with Ben Shapiro and various other “cancellation” targets. There’s something particularly perverse when it’s directed at ordinary people, say students who have their acceptances to ivy league schools rescinded because they said something racist on Twitter as a teenager. Surely, there needs to be some sort of social statute of limitations for informal penalties. That sort of thing certainly is new because the technology just didn’t exist twenty years ago. But I also think the appetite for penalizing people for wrongthink and wrongspeak wasn’t quite as pronounced in the early 2000s as it seems to be now.

“Free speech” is a stumbling block to intelligent discussions of this because the term is vague between concerns about rights and other sorts of moral concerns about speech norms. We’re not talking about First Amendment rights in most of these cases (though in Singer’s maybe we are). My view is that a rights paradigm isn’t very helpful here. The problem is that we don’t want to live in a society in which people do everything within their rights to punish others for expressing views that they disapprove of. A society like that is going to be a nasty, intolerant, insufferable place to live in regardless of where we draw the boundaries of the legal and moral rights of individuals. So I do insist that it really is an irreducibly cultural problem.

“There is a morally pressing issue here, and that issue is more important than the details of any specific argument, so you’ll excuse me if I don’t quibble with those details which I consider beside the point. Instead, I invite you to take the time to read what I and others have already written on this topic and defer to our superior insight.”

Hmmm… Maybe this really does point to a wider problem in our intellectual culture.

What?

Perhaps I was a bit uncharitiable in my reconstruction, but I couldn’t help but be struck by your insistence on the reality of the problem of ‘cancel culture’ combined with an apparent disinterest in the details of the skeptical argument you were mocking – which in many ways resembles the moral certitude and rush to judgment the participants in ‘cancel culture’ are often said to be guilty of.

In any case, you are having a much more productive conversation with the other Derek B, so I’m happy to bow out.

This does seem pretty determined to miss Derek Bowman’s point. There’s a difference between threatening someone’s job or interfering how they do the core functions of that job and wanting to deprive them of a perk like giving a talk. If students were arguing that someone should be fired for covering Singer in class or even publishing a paper sympathetic to his work that would be a different thing entirely or if they were arguing that professors shouldn’t be allowed to teach Singer that would also be hard to defend. But the issue here is whether Singer ought to be able to give a talk. Maybe he should. I tend to think so once he’s actually been invited though if I were the committee setting these things I’d fight tooth and nail not to invite him in the first place. But it’s just sloppy (at best) to put disinviting a speaker on the same level as trying to get people fired or meddling in how people teach in the actual classroom. Now I take it that some Rhodes faculty may have grounds to complain on that score given what some posters have said but Singer doesn’t.

The issue is whether there’s a culture that is attempting to “cancel” the opportunities that people who hold verboten views would otherwise have. And the attempt to cancel Singer’s invitation is an instance of that phenomenon. Furthermore, if someone who wasn’t in a position with the kind of job security that Singer has was faced with this kind of mob mentality, the distinction between cancelling a talk and getting fired from a job is pretty slim. So the issue is the culture of cancellation that episodes like this evince.

One incident or even several incidents do not prove a trend. If my friend tells me he got mugged that doesn’t prove that there’s a crime wave or even that the neighborhood is particularly dangerous. Nor does one snowy day here and there prove that climate change ain’t happening. All this stuff about “cancel culture” has the textbook hallmarks of a dumb moral panic like “stranger danger.” A few people (usually with an ideological axe to grind) focus on a few high profile cases without regard to the larger situation to argue for some grand horrifying trend that threatens our very way of life. And of course when someone actually does dig into the real data and finds it’s all incredibly overblown, which is exactly what this article does, the people who peddle moral panics do exactly what you’re doing and fall back on anecdote. One troubling thing here is that philosophers, who pride ourselves on such analytic acumen, keep making mistakes I’d flunk a student in critical thinking for. But while the sloppiness of all this is annoying and embarrassing it’s not the worst part. The worst part is that the very moral panic some people in the field are determined to whip up threatens to have the chilling effect on speech that they claim to be so worried about since many people will censor themselves out of fear of the boogeyman of the online mob.

Right Sam. Data proves trends. That’s the point of the Heterodox Academy articles: one set concerning changes in attitudes, and the other (mine) encouraging we look at whether behavior is changing.

@Sam Duncan. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2021/08/31/fire-launches-new-database-tracking-attacks-speech?fbclid=IwAR3Ttk2GHYDHFKgUUeWAH8Om5CmB4MWq8NG6fLPZ3vDpbp7v3MToImPfulo