“Purely vocational approach is embarrassingly out of touch”

Columbia College Chicago is facing a budget constraints and reportedly there are talks about addressing them by cutting programs in the liberal arts and sciences, and focusing more on career-based programs.

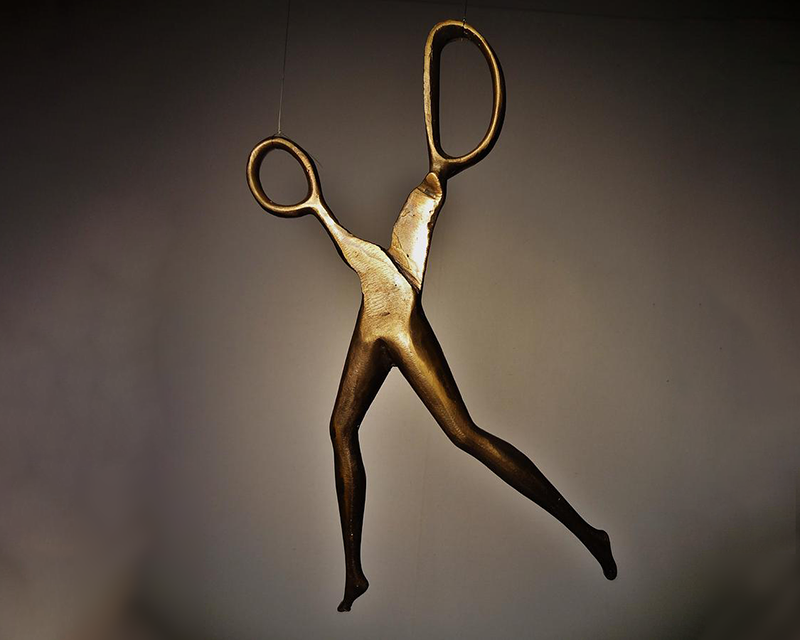

[Alexandra Goncharova, “Running with Scissors”]

He writes:

Currently, there is a disheartening movement afoot to shrink liberal arts and sciences curriculum to save money and close a budget shortfall. But students cannot just learn about game design and digital editing, and not learn about Islam, China, the history of slavery, logic or writing. That purely vocational approach is embarrassingly out of touch with what students need. If our academic core is cut too much, then the college will reap what it sows. Our future students will devolve into shallow careerists who risk becoming outdated in a few years because of rapidly changing tech innovations. Without liberal arts, students will lack the cultural awareness and critical thinking skills to adapt to and understand the fast-changing job markets of the future. They’ll also lack the social, cultural and historical knowledge to be active citizens in a democracy.

Columbia College Chicago is a unique vortex of creativity. But how creative and innovative will Columbia be if anti-intellectual forces at the college gut the core? There is no creativity without critical thinking and no critical thinking without creativity…

In an era when media, politics, and technology all converge to lock us into information bubbles and dogmatic silos, we need to recommit to a curriculum that breaks down walls and nudges people out of their comfort zones. The liberal arts do that –strengthening our sense of community and tolerance with those who are different from us. Our students will shape the images and narratives of the future, and we need to give them the tools to do this creative work with empathy and responsibility.

The full essay is at The Columbia Chronicle.

Related: The Demand for Philosophers.

what is the evidence for “The liberal arts do that –strengthening our sense of community and tolerance with those who are different from us”?

And given the thrust of the piece why are folks in the humanities so impotent when it comes to resisting (let alone overcoming) changes in political-economies that now threaten their own careers?

Yes. Defenders of the liberal arts so often implicitly style themselves as social scientists, making strong claims about the lifelong effects of studying the humanities. But I’ve never seen such a defense that was at all sensitive to how hard it is to establish claims about causation in social science, especially in education. Rather, it seems as if the implicit rule is that if you’re arguing against funding cuts, causal claims that would normally require empirical evidence can be supported by plausible-sounding armchair speculation.

I would love to learn that students who study liberal arts are better able to adapt to rapidly changing economic environments than students who pursue vocational majors. But I also recognize how hard it would be to get evidence for this claim that distinguished causation from correlation; students who pursue vocational majors tend to go to different schools, come from different backgrounds, etc., and I doubt you’ll find find many natural experiments that determine students’ majors. If there’s a compelling empirical literature on this, I’d love to hear about it, but my armchair guess would be that the evidence one would want to support claims like those in the essay linked in the OP doesn’t exist.

I’ve often heard the claim that defenders of the liberal arts make unsupported claims about the benefits of humanities education, but I’ve never seen a social scientific study proving that such claims are widespread, or a statistical comparison of how many such claims are presented with and without the backing of empirical research. Perhaps some enterprising social scientist can produce a meta-analysis for us, but until then it seems our discussion must come to a close.

I was talking about the difficulties specifically of supporting claims about causation. Supporting mere descriptive generalizations–e.g., philosophy majors often involve a logic component–is much easier.

If I’d offered some causal explanation for *why* defenses of the humanities so often make unsupported causal claims–e.g., if I said it’s because they studied humanities, and never took social science methods courses where they’d learn about causation–then you’d be well within your rights to suggest that I was hoisted by my own petard.

OK: but where are the studies that support the administrators’ claims that students don’t need the humanities? Have these administrators taken courses where they learn about causation? Are are they relying on a priori guesses about which majors “sound practical” and such? Genuinely asking.

100% agreed! I think this is a frustrating area where we have to make decisions based on less data than we’d like, and it bothers me when people overstate the case for their preferred policies. I didn’t mean to say that the data we have clearly favors one side over the other.

Let’s say that students take courses in which they delve into and debate, among other things, the “ideals of individual freedom and toleration; of democratic government; of respect for the rights of minorities and for human rights generally….” Are these students likely to be more thoughtful voters and maybe more politically engaged and active citizens than they would be otherwise? On the one hand, it may be hard to prove that claim or supposition; on the other hand, it’s plausible enough that it may not really need a social-scientific demonstration.

p.s. The quote is from Anthony Kronman, Education’s End (2007), as quoted by Andrew Delbanco in College (2012), p. 31.

I love that stuff! Hooray for delving into and debating ideals of freedom and toleration, democratic government, and respect for rights of minorities and human rights generally.

But no, I wouldn’t exempt Kronman from this charge. In general, the education literature is full of studies of educational interventions that sound nice, but where when you look for long term effects, you find little or nothing. (Freddie DeBoer’s “The Cult of Smart” is a nice book that surveys some of the depressing empirical literature.)

I don’t mean to be coming from a generic “don’t say anything unless you have statistics” place, but from a more specific “long term causal effects on measurable outcomes of studying particular subjects in school tend to be indistinguishable from zero” place.

Arum and Roksa provide a fair amount of evidence that humanities are particularly good at developing general thinking skills in their “Academically Adrift.” Of course humanities aren’t magic or unique here. Math and the hard sciences also do well in this score too. But many “applied” or “vocational” degrees don’t. Students who study business for instance don’t show any statistically significant improvement in thinking skills. It’s worth noting that math departments are also one of the more commonly targeted ones for cuts from what I can tell whereas I’ve yet to see any administrators take the axe to business.

Do they address the difficulties of comparing like with like? I’d expect that students who major in vocational subjects differ in all sorts of ways–backgrounds, interests, abilities–from students who major in the liberal arts. If I heard some claim about how math majors fare after college, or how much they learn in college, I’d immediately wonder how to distinguish the effect of studying math, from the effect of being the kind of student who willingly decides to major in math.

I don’t mean this in a gotcha sense–I’d be really happy to hear that they do, and in general I’d love to learn that claims in the post linked in the OP are well supported.

This feels a little bit like Descartes has entered the chat.

“Well supported” certainly does not mean “every possible or even reasonable confound addressed.”

Selection effects are ubiquitous in education. Worrying about them isn’t pedantic–rather, if you see that students in a particular major, or who go to a particular school, end up doing better than others, your default should be that a big part of the effect is that those students started out different from the other students.

E.g., just one example, a famous David Card study found that much of the earnings gap between students at more selective colleges and students at less selective colleges disappears when you look at students at less selective colleges who were admitted to more selective ones, but didn’t go.

The literature is full of stuff like that. The 2021 nobel prize in economics was awarded to some economists who made it embarrassing–within their discipline–to make causal claims without trying really hard to rule out confounds like the ones above. But that doesn’t mean economists have become Cartesian skeptics.

agreed – so do the studies show that the “practical” majors that aren’t being cut do better? Since selection effects in education are ubiquitious, isn’t caution about the administrators claims warranted, as well as caution about the humanities evangelists?

I once suggested this slogan for Pitt HPS:

“HPS majors have a higher-than-average GPA and out-earn most other majors. If you want to learn why this isn’t a good reason to major in HPS, you should major in HPS!”

If memory serves, their method was to compare collegiate learning assessment scores of groups of students both pre and post college study and within their courses of study. I don’t think they tested the same individual students multiple times but they compared the same groups at the same institutions. So in short, yes they are aware of these sorts of issues.

Can you explain how that addresses Daniel’s concern? Because I don’t quite see it. (This is a good-faith question on my part :))

This isn’t evidence per se (which others have noted is very hard to come by here, given the entangled variables that are difficult to control), but a reason to believe the claim:

Do you think not having a liberal-arts education, e.g., only a STEM education, is more effective in strengthening our sense of community and tolerance with those who are different from us? That is, does ignoring or not studying other groups, cultures, etc. promote empathy?

Why would you think so? Seems that it would do the opposite: fortify our echo chambers and better enable us to dehumanize others. Empathy requires exposure and understanding of other perspectives. You get that mainly or maybe even only from a liberal-arts education.

Certainly, empathy is never guaranteed; there are plenty of deplorable liberal-arts graduates. But that’s not evidence against the claim by itself.

Not to mention the same people who have been administrating education into these budget shortfalls are trained in the exact programs that they deem worthwhile.

John McCumber, “How the humanities are useful”

If studying the liberal arts is a hedge against shallow careerism, why are there so many shallow careerists in philosophy?

Because “hedge” doesn’t mean “guarantee.”

No one ever claimed that studying (of any kind) is sufficient all by itself to change a person for the better. There are many other variables in play.

Thanks. I agree. But I think you’re being uncharitable: it strains belief to think I thought this alone would be sufficient.

Here’s a more charitable interpretation: the claim in play is whether studying the liberal arts protects against shallow careerism all else being equal.

My fifteen years in academia show this is almost certainly false.

Sorry—when you post anonymously, it’s hard to know what level of charity is appropriate to give. And I still don’t know.

It’s not a stretch of the imagination to think that someone, even many people, would make such a mistake in reasoning. We have critical thinking courses because those mistakes are so common; and I know that not everyone commenting on Daily Nous is a professional philosopher.

Regardless, your interpretation might not be any more charitable than mine, esp. if you think you’ve credibly tested the claim, much less falsified it. The “all things being equal” is the tricky part, cet. par.

So, what is your evidence, across 15 years in academia, that the claim is false? You said you agreed with my statements, so I’m curious how you were able to isolate and control those many other variables in order to properly test the claim?

The bit

“But students cannot just learn about game design and digital editing, and not learn about Islam, China, the history of slavery, logic or writing.”

reminds me that some activities/professions are more (much more) self-enclosed than others: you don’t need to be good at (or even know) anything else in order to be good at chess, or mathematics/computing science, music, Go, or poker, for example. Also, some of the most (maybe the most) successful modern games ever – thinking of Pac Man, Tetris, Mario and Mega Man, (the match-three format in general but especially) Candy Crush – are (mostly storyless and) all about mechanics/game design, so *maybe some (adult) people can in fact choose* to just learn game design and not be required (forced) to endure more stuff they may be not interested at all in to begin with