Philosophy as Sustaining Faith in our Cognitive Agency

“What are the practices that sustain our faith in ourselves as the agents of our thinking?”

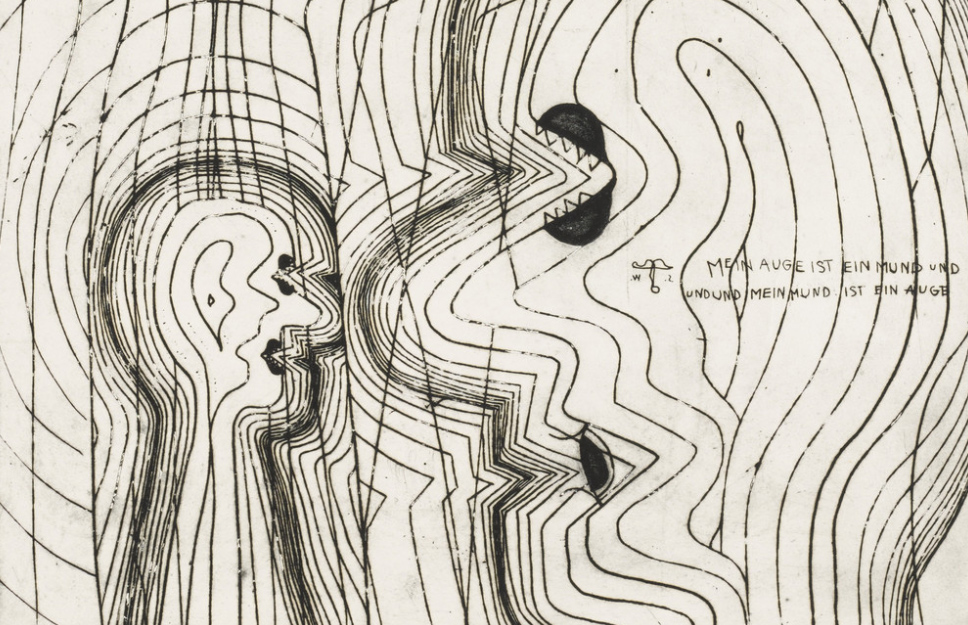

[Dieter Roth, “my eye is a mouth” (detail)]

In “Faith and World,” Gomes discusses the complaint that George Christoph Lichtenberg makes against Descartes’ attempt to establish the his own existence as a thinking thing:

Descartes’s starting point is not isolationist enough, he says, for it involves claims to which he is not entitled. “One should say it is thinking, just as one says, it is lightning. To say cogito is already too much as soon as one translates it as I am thinking. To assume the I, to postulate it, is a practical requirement.”

What does this complaint amount to? Gomes says:

Lichtenberg is not making a claim about the possibility of a subjectless episode of thinking. The idea is not that Descartes needs to rule out the possibility of thoughts without a subject in order to move from self-consciousness to the world.

Lichtenberg is rather raising a question about our entitlement to think of ourselves as the agent of our thinking. Sometimes thoughts strike us like lightning. When this happens, we are their patient. It is central to our self-conscious lives that this is the exception: we are first and foremost the instigating agents of our thinking. The question raised by Lichtenberg is: with what right do we think of ourselves as such?

The “faith” Gomes is interested in is each person’s faith that the thinking in their head is something they are doing, and not merely something that is happening to them (perhaps via the agency of others).

Lichtenberg’s remarks show that we must have faith in ourselves as the agents of our thinking. But faith can be undermined and it can be sustained. This is a central theme of the final part of Iris Murdoch’s Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals, a work which has no interest in the Cartesian and Kantian projects.

Murdoch instead draws attention to the beliefs, experiences, practices, and rituals which religion once provided for us and which she thinks need to be co-opted to support our search for the good. Kant, too, recognizes the way that specific human institutions such as the historical church can sustain articles of faith. And this provides us with a connection to the world, since our faith in ourselves as the agents of our thinking can be and is sustained by beliefs, experiences, and practices that relate us to the world. Self-conscious subjects must have faith in themselves as thinking agents, and it is our relations to the world that sustain this faith.

And so he asks: “What are the practices that sustain our faith in ourselves as the agents of our thinking?” Here’s his partial answer:

Prime among them is the practice of holding and being held accountable for one’s judgements. Consider philosophical discussion. At its best, it involves holding people accountable for their views. When you tell me that there are no such things as chairs, I take you at your word. I may ask for reasons. I will criticize your view. (“What is this I am sitting on?!”) It would not make sense to engage in these practices if you were programmed to hold your views or if your thoughts struck you like Lichtenberg’s lightning. The questions and challenges involved in philosophical discussion are part of a practice in which we hold each other accountable for our thinking…

To hold someone accountable for their judgement is take that judgement to be imputable to them. It is to take them as the agent of their thinking. The practice of being held accountable provides us with a framework with which to sustain the idea that we are the agents of our thinking. It is not necessary for this faith. But nor is it irrelevant. Like the stories, images, and rituals that make up a religious tradition, it is a way of shoring up that assent we make on practical grounds alone.

Gomes is thus offering an explanation of one way in which philosophy is valuable: it is an activity that centrally involves a set of practices that, by holding us accountable for our thoughts, helps sustain our faith in our own cognitive agency.

You can read the whole piece here.

By the way, the editors of The Raven have announced that the magazine is now paying $500 per essay and $250 for reviews and other short pieces.

For my money, the topic of mental action or cognitive agency is both deeply important and widely overlooked, despite efforts to the contrary (such as this bit of shameless self-promotion, for instance).

It would be moving too quickly to assert with Gomes that my assumption that I’m a conscious subject who recognizes myself as the agent of my own thinking is “unsupported”, presumably by some kind of evidence. In fact, the very distinction Gomes highlights – between being patient and being agent with respect to self-conscious episodes of thinking – supports the assumption that, at least some of the time, I’m an agent of my own thinking. And, if we dig a little deeper into what might be happening during the latter sorts of episodes, we can bring to light additional support for the claim to self-conscious cognitive agency.

Regardless of all that, thanks for sharing this piece.