Percentage of Women Philosophy Majors Has Risen Sharply Since 2016 — Why? Or: The 2017 Knuckle (guest post)

What explains the recent sharp increase in women philosophy majors?

In the following, Eric Schwitzgebel (UC Riverside) presents data showing an increase in the percentage of women majoring in philosophy over the past six years, and puzzles over some possible explanations for the change.

(A version of this post previously appeared at The Splintered Mind.)

[photo of “Mood & Quantify” by Laurie Frick]

Percentage of Women Philosophy Majors Has Risen Sharply Since 2016 — Why?

Or: The 2017 Knuckle

by Eric Schwitzgebel

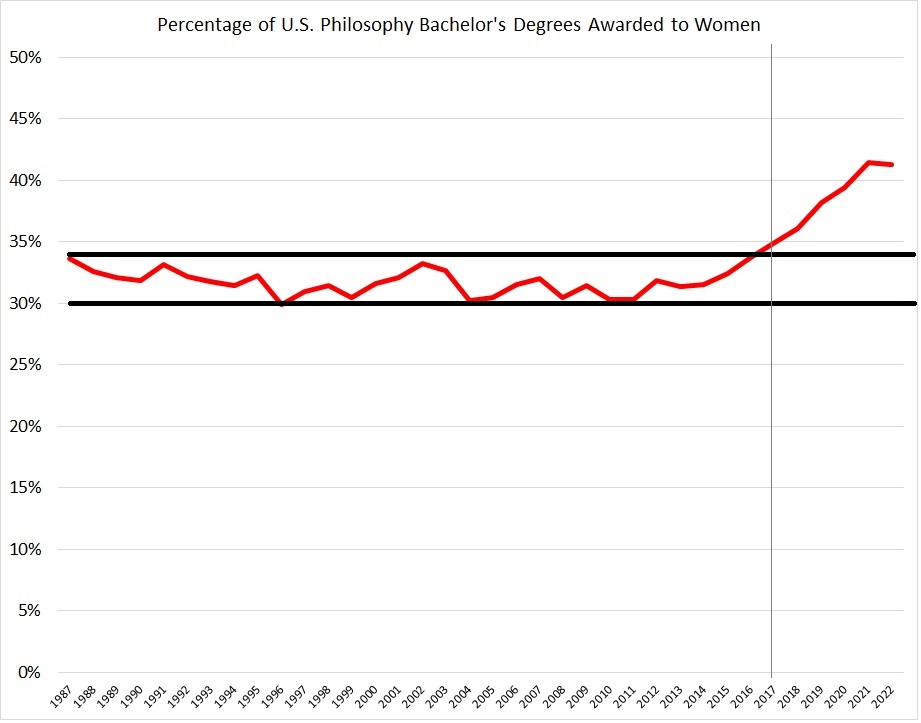

Back in 2017, I noticed that the percentage of women philosophy majors in the U.S. had been 30%-34% for “approximately forever”. That is, despite the increasing percentage of Bachelor’s degrees awarded to women overall and in most other majors, the percentage of philosophy Bachelor’s degrees awarded to women had been remarkably steady from the first available years (1986-1987) in the NCES IPEDS database through the then-most-recent data year (2016).

In the past few years, however, I have noticed some signs of change. The most recent NCES IPEDS data release, which I analyzed recently, statistically solidifies the trend. Women now constitute over 40% of philosophy Bachelor’s degree recipients.

I would argue that this is a very material change from the long-standing trend of 30-34%. If parity is 50%, a change from 32% women to 41% women constitutes a halving of the disparity. Furthermore, the change has been entirely in the most recent six years’ of data—remarkably swift for this type of demographic shift.

The chart below shows the historical trend through the most recent available year (2022). I’ve marked the 30%-34% band with thick horizontal lines. A thin vertical line marks 2017, the first year to cross the 34% mark (34.9%). The most recent years are 41.4% and 41.3% respectively.

Given the knuckle-like change in the slope of the graph, let’s call this the 2017 Knuckle.

What I find puzzling is why?

This doesn’t reflect an overall trend of increasing percentages of women across majors. Overall, women have been 56%-58% of Bachelor’s degree recipients throughout the 21st century. Most other humanities and social sciences had a much earlier increase in the proportion of women.

However, interestingly, the physical sciences and engineering, which have also tended to be disproportionately men, have showed some similar trends. Since 2010, physics majors have increased from 40% to 45% women—with all of that increase being since 2017. Since 2010, Engineering has increased from 18% to 25% women, with the bulk of the increase since 2016. Since 2010, “Engineering Technologies and Engineering-related Fields” (which NCES classifies separately from Engineering) has also increased from 10% to 15% women, again with most of the increase since 2016. Among the humanities and social sciences, Economics is maybe the only large major similar to Philosophy in gender disparity, and in Economics we see a similar trend, though smaller: an increase from 31% to 35% women between 2010 and 2022, again with most of the gain since 2016.

Since people tend to decide their majors a few years before graduating, whatever explains these trends must have begun in approximately 2013-2016, then increased through at least 2020. Any hypotheses?

It’s probably not a result of change in the percentage of women faculty: Faculty turnover is slow, and at least in philosophy the evidence suggests a slow increase over the decades, rather than a knuckle. (Data are sparser and less reliable on this issue, but see here, here and here.) There also wasn’t much change in the 2010s in the percentage of women earning Philosophy PhDs in the U.S.

A modeling hypothesis would suggest that change in the percentage of women philosophy majors is driven by a change in the percentage of women faculty and TAs in Philosophy. In contrast, a pipeline hypothesis predicts that change in the percentage of women philosophy majors leads to a change in the percentage of women graduate students and (years later) faculty. Both hypotheses posit a relationship between women undergraduates and women instructors, but with different directions of causation. (The hypotheses aren’t, of course, incompatible: Causation might flow both ways.) At least in Philosophy, the modeling hypothesis doesn’t seem to explain the 2017 Knuckle. Concerning the pipeline, it’s too early to tell, but when the NSF releases their data on doctorates in October, I’ll look for preliminary signs.

I’m also inclined to think—though I’m certainly open to evidence—that feminism has been slowly, steadily increasing in U.S. culture, rather than being more or less flat since the late 1980s and recently increasing again. So a general cultural increase in feminist attitudes wouldn’t specifically explain the 2017 Knuckle. Now it is true that 2015-2017 saw the rise of Trump, and the backlash against Trump, as well as the explosion of the #MeToo movement. Maybe that’s important? It would be pretty remarkable if those cultural events had a substantial effect on the percentage of women undergraduates declaring Philosophy, Economics, Physics, and Engineering majors.

Further thoughts? What explains the 2017 Knuckle?

It could be interesting to look at other countries, and at race/ethnicity data, and at majors that tend to be disproportionately women—patterns there could potentially cast light on the effect—but enough for today.

Methodological notes:

NCES IPEDS attempts to collect data on every graduating student in accredited Bachelor’s programs in the U.S., using administrator-supplied statistics. Gender categories are binary “men” and “women” with no unclassified students. Data are limited to “U.S. only” institutions in classification category 38.01 (“Philosophy”) and include both first and second majors back through 2001. Before 2001, only first majors are available. Each year includes all graduates during the academic year ending in that year (e.g., 2022 includes all students from the 2021-2022 academic year). For engineering and physical sciences, I used major catories 15, 16, and 40; and for Economics, 45.06.

The only really swift change I know of in this period is the decline of the other humanities. Check the overall enrollment of women in humanities majors; maybe the increase represents part of a larger shift away from other disciplines.

Yes, worth a check!

Could one factor be that the *total number* of philosophy majors (or students in Arts & Sciences more generally) has been falling–or falling as a percentage or total university majors–and that could be creating more statistical “noise” in the system? Like 350/1000 people is one thing, but would 180/400 have the same evidential value? (Guess there’s p-values and all that, maybe doesn’t matter.)

Could another be that fewer people–maybe especially fewer men–are going to college at all? Or that women are increasingly more likely to go to college than men?

I guess the theories I’m looking at here aren’t really about women and philosophy per se; they’re broader demographic trends that’d point to the optics of that, and might generalize across other fields (including the ones you’ve listed). Thanks for sharing the research!

Good questions. The data I supplied in the post leaves those hypotheses open, but the detailed data doesn’t support them. The numbers are ~5000/year, so it’s can’t be statistical chance. Generally, university completions were up during the period (though with a dip last year). The total number of philosophy majors fell dramatically from 2010 to 2016, but since then it’s been approximately flat.

Interesting. I guess it’s hard to make good guesses without further information about the absolute numbers. Is the amount of men doing philosophy major remains the same? If it decreased, maybe part of the task is to explain the decrease in men. If women are still 56%-58% of college students and the percentage of women increases in some fields, it must go down in others. Which fields are they?

Raw numbers, men, 2000-2022: 3242 3962 4358 4727 5376 5763 5842 5807 6107 6169 6460 6480 6380 6469 6042 5534 4967 4928 4900 4994 4975 4877 4675.

Raw numbers, women, 2000-2022: 1498 1874 2171 2296 2331 2520 2690 2734 2671 2827 2808 2812 2982 2958 2778 2650 2522 2644 2767 3080 3234 3451 3283

Regarding other fields — yes, I might do some follow-up exploration of that. It could be interesting to see if some of the fields with a high percentage of women majors are also moving more toward parity.

Combining this with BCB’s observation, it’s at least statistically possible that the percentage of women has increased in all disciplines, even as the overall percentage of women in university remains constant, as long as disciplines that historically had high percentages of women shrink, and disciplines that historically had low percentages of women grow. (This would be a classic instance of Simpson’s Paradox.)

Is it possible shifts in curriculum at the introductory level have had an impact? I know many editors of intro books promoted increased diversity of authors and topics in their texts, and this often meant more female authors. Also, many faculty who teach these courses have made changes to their course content to include more women philosophers. There was evidence that women drop off most between taking an intro course and becoming a major, and it was hypothesized that this was because women don’t see themselves represented in Philosophy.

I’m not sure about this… There’s arguably a similar lack of representation in the core works of the social sciences, but there are plenty of women majoring in those fields. I think cultivating a welcoming culture and rooting out the gross old men of philosophy is way more important to bolstering enrollment. In my experience, men dominating discussion and being kind of asshole-ish in class is a much bigger reason why female majors drop their major.

I am one of the women who left philosophy after doing the intro course (and entering with a high degree of interest). There were so many rumours about how “hard” philosophy was (in particular the 2nd year M&E course) that I dropped it thinking I wasn’t good enough. This despite getting a high A in the intro course. I suspect lack of confidence and an overinflated idea of philosophy’s difficulty puts off some female students.

(1) hardly any students read the syllabus, (2) even fewer look at the authors we’ll be reading over the semester, (3) even fewer look at the sex of the authors we’ll be reading over the semester, (4) even fewer care about the sex of the authors we’ll be reading over the semester, (5) those who made it this far are so few and probably won’t decide not to major in philosophy because of syllabus representation. But if they do decide not to major because of it, the numbers probably aren’t significant.

So, I think it’s incredibly unlikely that syllabus diversifying makes a significant difference.

I don’t know if diverse syllabi matter. However, I think the idea that “students don’t read the syllabus” so therefore the sex of the authors doesn’t matter is odd. Sure, they may not read the syllabus, but they read the readings (hopefully!). They discuss the authors’ views, they are presented with philosophers’ views and arguments in lectures. All these places students will hear the sex of the philosophers in question, not just by reading their names in the syllabus.

It would be interesting to see if there was a systematic shift in syllabae around that time.

Hypothesis: Over a decade ago, a ton of brave women began speaking out boldly about what it is like to be a woman in philosophy, bringing attention to a very serious problem (https://beingawomaninphilosophy.wordpress.com/). A non-insignificant number of philosophers and philosophers-in-training paid attention and began making changes (personal and institutional). Old guard professors began retiring/dying. More women (and supportive men) were hired to take their place. These women have done a hell of a job recruiting other women into the discipline.

I do think the individual efforts of individual philosophers (and presumably physicists and engineers) have to be part of the story.

The work we published from my department showed that every single women in the focus group of women who had taken more than 1 philosophy class could point to faculty who ‘tapped’ them and encouraged them to take more classes. When I do this, almost every women says something about how surprised they are that I think they are suited to philosophy and good at philosophy; and many sign up for another class (or consider majoring or minoring).

What if the change is due to the efforts of philosophy faculty that shows up as invitations and encouragement?

Gen Z is different – hypothesis: this recent trend is less about us (current philosophy departments and faculty) and more about them.

Is the idea in part that they might have a greater tendency to buck norms?

You seem to be suggesting that what explains the disproportionately low percentage of women in philosophy is their own beliefs and desires.

I don’t know exactly what makes Gen Z different. I’m definitely not suggesting this explanation of the status quo – those people weren’t Gen Z and might have had different experiences and causes in play.

The proportion of women in college relative to men has shifted in favor of women in the last few years (https://www.statista.com/statistics/184272/educational-attainment-of-college-diploma-or-higher-by-gender/) and crossed over around 2017.

All those women have to go somewhere (the pigeonhole principle).

It’s possible the shift in the philosophy gender ratio is just part of that larger trend across the university.

I would love to see more data on this.

The Good Place (2016-2020).

Half seriously.