How to Tell Whether an AI Is Conscious (guest post)

“We can apply scientific rigor to the assessment of AI consciousness, in part because… we can identify fairly clear indicators associated with leading theories of consciousness, and show how to assess whether AI systems satisfy them.”

In the following guest post, Jonathan Simon (Montreal) and Robert Long (Center for AI Safety) summarize their recent interdisciplinary report, “Consciousness in Artificial Intelligence: Insights from the Science of Consciousness“.

The report was led by Patrick Butlin (Oxford) and Robert Long, together with 17 co-authors.[1]

How to Tell Whether an AI is Conscious

by Jonathan Simon and Robert Long

Could AI systems ever be conscious? Might they already be? How would we know? These are pressing questions in the philosophy of mind, and they come up more and more in the public conversation as AI advances. You’ve probably read about Blake Lemoine, or about the time Ilya Sutskever, the chief scientist at OpenAI, tweeted that AIs might already be “slightly conscious”. The rise of AI systems that can convincingly imitate human conversation will likely cause many people to believe that the systems they interact with are conscious, whether they are or not. Meanwhile, researchers are taking inspiration from functions associated with consciousness in humans in efforts to further enhance AI capabilities.

Just to be clear, we aren’t talking about general intelligence, or moral standing: we are talking about phenomenal consciousness—the question of whether there is something it is like to be an instance of the system in question. Fish might be phenomenally conscious, but they aren’t generally intelligent, and it is debatable whether they have moral standing. Same here: it is possible that AI systems will be phenomenally conscious before they arrive at general intelligence or moral standing. That means artificial consciousness might be upon us soon, even if artificial general intelligence (AGI) is further off. And consciousness might have something to do with moral standing. So there are questions here that should be addressed sooner rather than later.

AI consciousness is thorny, between the hard problem, persistent lack of consensus about the neural basis of consciousness, and unclarity over what next year’s AI models will look like. If certainty is your game, you’d have to solve those problems first, so: game over.

For the report, we set a target lower than certainty. Instead we set out to find things that we can be reasonably confident about, on the basis of a minimal number of working assumptions. We settled on three working assumptions. First, we adopt computational functionalism, the claim that the thing our brains (and bodies) do to make us conscious is a computational thing—otherwise, there isn’t much point in asking about AI consciousness.

Second, we assume that neuroscientific theories are on the right track in general, meaning that some of the necessary conditions for consciousness that some of these theories identify really are necessary conditions for consciousness, and some collection of these may ultimately be sufficient (though we do not claim to have arrived at such a comprehensive list yet).

Third, we assume that our best bet for discovering substantive truths about AI consciousness is what Jonathan Birch calls a theory-heavy methodology, which in our context means we proceed by investigating whether AI systems perform functions similar to those that scientific theories associate with consciousness, then assigning credences based on (a) the similarity of the functions, (b) the strength of the evidence for the theories in question, and (c) one’s credence in computational functionalism. The main alternatives to this approach are either 1) to use behavioural or interactive tests for consciousness, which risks testing for the wrong things or 2) to look for markers typically associated with consciousness, but this method has pitfalls in the artificial case that it may not have in the case of animal consciousness.

Observe that you can accept these assumptions as a materialist, or as a non-materialist. We aren’t addressing the hard problem of consciousness, but rather what Anil Seth calls the “real” problem of saying which mechanisms of which systems—in this case, AI systems—are associated with consciousness.

With these assumptions in hand, our interdisciplinary team of scientists, engineers and philosophers set out to see what we could reasonably say about AI consciousness.

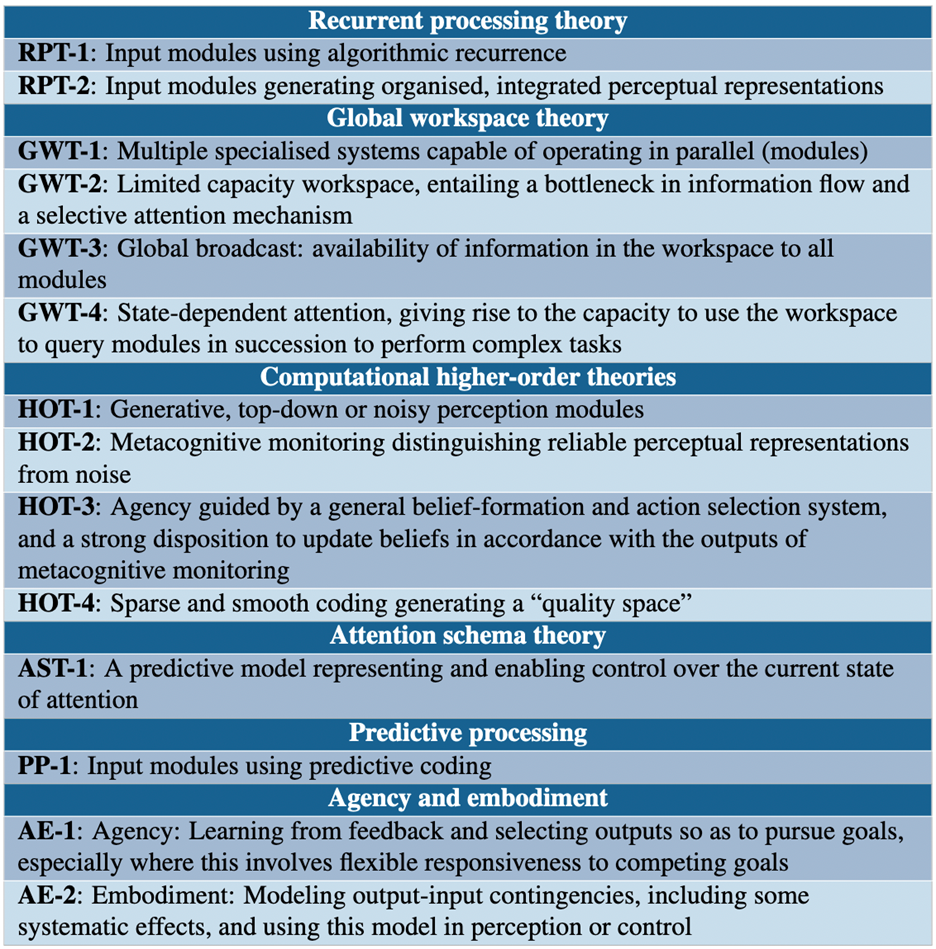

First, we made a (non-exhaustive) list of promising theories of consciousness. We decided to focus on five: recurrent processing theory, global workspace theory, higher- order theories, predictive processing, and attention schema theory. We also discuss unlimited associative learning and ‘midbrain’ theories that emphasize sensory integration, as well as two high-level features of systems that are often argued to be important for consciousness: embodiment and agency. Again, this is not an exhaustive list, but we aspired to cover a representative selection of promising scientific approaches to consciousness that are compatible with computational functionalism.

We then set out to identify, for each of these, a short list of indicator conditions: criteria that must be satisfied by a system to be conscious by the lights of that theory. Crucially, we don’t then attempt to decide between all of the theories. Rather, we build a checklist of all of the indicators from all of the theories, with the idea that the more boxes a given system checks, the more confident we can be that it is conscious, and likewise, the fewer boxes a system checks, the less confident we should be that it is conscious (compare: the methodology in Chalmers 2023).

We used this approach to ask two questions. First: are there any indicators that appear to be off-limits or impossible to implement in near future AI systems? Second, do any existing AI systems satisfy all of the indicators? We answer no to both questions. Thus, we find no obstacles to the existence of AI systems in the near future (though we offer no blueprints, and we do not identify a system in which all indicators would be jointly satisfied), but we also find no AI systems that check every box and would be classified as conscious according to all of the theories we consider.

In the space remaining, we’ll first summarize a sample negative finding: that current large language models like ChatGPT do not satisfy all indicators, and then we’ll discuss a few broader morals of the project.

We analyze several contemporary AI systems: Transformer-based systems such as large language models and PerceiverIO, as well as AdA, Palm-E, and a “virtual rodent”. While much recent focus on AI consciousness has understandably focused on large language models, this is overly narrow. Asking whether AI systems are conscious is rather like asking whether organisms are conscious. It will very likely depend on the system in question, so we must explore a range of systems.

While we find unchecked boxes for all of these systems, a clear example is our analysis of large language models based on the Transformer architecture like OpenAI’s GPT series. In particular we assess whether these models’ residual stream might amount to a global workspace. We find that it does not, because of an equivocation in how this would go: do we think of modules as confined to particular layers? Then indicator GWT-3 (see the above table) is unsatisfied. Do we think of modules as spread out over layers? Then there is no distinguishing the residual stream (i.e., the workspace) from the modules, and indicator GWT-1 is unsatisfied. Moreover, either way, indicator RPT-1 is unsatisfied. We then assess Perceiver and PerceiverIO architectures, finding that while they do better, they still fail to satisfy indicator GWT-3.

What are the morals of the story? We find a few: 1) we can apply scientific rigor to the assessment of AI consciousness, in part because 2) we can identify fairly clear indicators associated with leading theories of consciousness, and show how to assess whether AI systems satisfy them. And as far as substantive results go, 3) we found initial evidence that many of the indicator properties can be implemented in AI systems using current techniques, while also finding 4) that no current system satisfies all indicators and would be classified as conscious according to all of the theories we consider.

What about the moral morals of the story? All of our co-authors care about ethical issues raised by machines that are, or are perceived to be, conscious, and some of us have written about them. We do not advocate building conscious AIs, nor do we provide any new information about how one might do so: our results are primarily results of classification rather than of engineering. At the same time, we hope that our methodology and list of indicators contributes to more nuanced conversations, for example, by allowing us to more clearly distinguish the question of artificial consciousness from the question of artificial general intelligence, and to get clearer on which aspects or functions of consciousness are morally relevant.

Thanks for reading! You can also find coverage of our report in Science, Nature, New Scientist, the ImportAI Newsletter, and elsewhere.

[1] The full set of authors is: Patrick Butlin (Philosophy, Future of Humanity Institute, University of Oxford), Robert Long (Philosophy, Center for AI Safety), Eric Elmoznino (Cognitive neuroscience, Université de Montréal and MILA – Quebec AI Institute), Yoshua Bengio (Artifical Intelligence, Université de Montréal and MILA – Quebec AI Institute), Jonathan Birch (Consciousness science, Centre for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science, LSE), Axel Constant (Philosophy, School of Engineering and Informatics, The University of Sussex and Centre de Recherche en Éthique, Université de Montréal), George Deane (Philosophy, Université de Montréal), Stephen M. Fleming (Cognitive neuroscience, Department of Experimental Psychology and Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London) Chris Frith (Neuroscience, Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, University College London and Institute of Philosophy, University of London) Xu Ji (Université de Montréal and MILA – Quebec AI Institute), Ryota Kanai (Consciousness science and AI, Araya, Inc.), Colin Klein (Philosophy, The Australian National University), Grace Lindsay (Computational neuroscience, Psychology and Center for Data Science, New York University), Matthias Michel (Consciousness science, Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness, New York University), Liad Mudrik (Consciousness science, School of Psychological Sciences and Sagol School of Neuroscience, Tel-Aviv University), Megan A. K. Peters (Cognitive science, University of California, Irvine and CIFAR Program in Brain, Mind and Consciousness), Eric Schwitzgebel, (Philosophy, University of California, Riverside), Jonathan Simon (Philosophy, Université de Montréal), Rufin VanRullen (Cognitive science, Centre de Recherche Cerveau et Cognition, CNRS, Université de Toulouse).

[Top image by J. Weinberg, created with the help Dall-E 2 and with apologies to Magritte]

To recognize consciousness, one would have to a) arrive at a consensus definition of what consciousness is, b) be able to consistently distinguish the manifestations of brain activity which indicate consciousness from those that don’t, and c) identify the minimum functional states of the constellation of manifestations of brain activity necessary to produce consciousness.

At the moment, no one can plausibly argue to have arrived at either (a), (b) or (c). That is, we can only say, and be met with general agreement, that we sense our own (human) consciousness, and that it appears to be the product of activities occurring in the brain. We have insufficient evidence to support any claim more extensive than that, and even the statement ‘product of activities occurring in the brain might be reductive and inaccurate.

More than three decades of research into embodied cognition, enactive cognition, and situated cognition describe a dynamic relationship between an organism’s central nervous system in its entirety (not simply the brain in skull), and the body moving about the environment it inhabits, are at the very least integral constituents of consciousness, if not in fact composing the substrate of consciousness.

At the moment, the most sophisticated AI does two, and only two, things- 1) compile information, and 2) sort information. It compiles data relatively quickly, although even with intensive oversight by human handlers, it does so haphazardly (no AI yet constructed can, without human review, reliably separate information to be included in its search from that to be excluded). When asked to sort the information collected, it does so poorly, unable to consistently recognize accurately categorized information from spurious, at times laughably absurd output. Proponents of the view that AI is nearly conscious, or perhaps displays flickerings of conscious activity, refer to such errors as ‘hallucinations’, assigning a label of a particular form of (pathological) human experience to the machine, betraying the conviction that consciousness is to some extent present in AI. This label, unfortunately, is grossly misapplied, since hallucinations are a psychological phenomenon during which sensory experience is aberrantly interpreted by the brain. AI has no such independent sensory experience to interpret. It lacks sensorium entirely.

This misapplication of a psychological concept is perhaps fortuitous in another way, because it highlights a crucial feature that healthy human brains (and those of

other animals as well) possess that AI does not, and ultimately cannot, possess- the exercise of judgment. There are good reasons to think that ‘higher order consciousness’ is predicated upon the CNS’s interpretation of sensorium, which manifests as affect.

When proponents of the notion that AI, which presently consists of rapid iterations of simulacra of splinter elements of cognition, is approaching consciousness, they neglect each of these aspects- sensorium, affect, and judgement. This neglect is not surprising, because no AI can be constructed that displays these elements– sensorium and affect– and so no AI can exercise independent judgement.

To pose it as a question- would anyone claim that a device (or organism) that lacks sensorium, affect, and independent judgement is conscious in any meaningful way?

To answer in the affirmative would entail an exercise in redefinition of the construct ‘consciousness’, so diluting it that we’re no longer talking about the same thing as human consciousness, and solely for the dubious purpose of claiming ‘AI is or can be conscious’, and at the same time contending this redefined consciousness is tantamount to human consciousness.

Even if unintended, we need to be cautious about this conceptual bait and switch, which discussions of consciousness are unfortunately prone to.

Hi Ian,

On your criterion a), I’m not sure how to understand your claim that to recognize X, we first need a consensus definition of X. You can be engaged in a verbal dispute with me, where you and I don’t agree on how to use a term, but you can still know what you mean by the term, recognize instances of it, etc. Also, another kind of thing that sometimes happens is that you know it when you see it, even if you can’t define it. Here, though, we’ve got a fairly clear consensus that by `phenomenal consciousness’ we mean what Thomas Nagel is talking about: the kind of state that there is something it is like to be in.

On your criterion b), we’re mainly concerned with saying which systems are conscious, not which states of which systems are conscious.

On your criterion c), that is what we are trying to do!

As to the rest of the things you say: there is a lot there. We talk about both embodiment and agency (related to enactivity and to affect) in the paper. We also allow that AI systems might have analog transducers and actuators. I’m not sure quite what you mean by `judgment’ – maybe you have in mind Brian Cantwell Smith’s distinction between reckoning and judgment? That seems more relevant to the debate about AGI than the debate about artificial consciousness: remember, we maintain that AI systems might be conscious without enjoying human level intelligence.

Thanks for the detailed reply.

I hope not to end up talking past each other in a disagreement about terms, but sometimes the terms we use are the ballgame.

If we arrive at, for the sake of discussion, agreement on (a), a statement about what consciousness is or consists of, and we wish to determine if any other entity besides humans (whether human constructed or biological) also displays this very same thing we call consciousness, we need to identify what it is going on with that potentially conscious entity that affords it consciousness, which is what I attempted to capture with (b). Here’s why.

At the moment, we are constrained by comparison with or analogy to the one entity we are generally satisfied is conscious- the human brain-body system. It’s what we have to work with as a reference standard, and even if we permit speculation about ‘consciousness, but not limited to only the human sort’, we are in peril of making the term consciousness so slippery we can’t, at some point, grasp if we are still talking about the same thing.

Is Nagel’s bat conscious in the same way a human might be? Humans and bats both have mammalian nervous systems, as do dolphins, and raccoons. Are all mammals conscious, in the way we ordinarily understand humans are conscious? If conscious, but not the same, what are those shared characteristics we can observe that tell us consciousness is present? Octopi sure seem conscious to me, but there is not universal agreement on this, precisely because we haven’t settled what constitutes consciousness.

One way we determine this with humans is the presence or absence of activity, or degree of activity, in various cortical regions. Non-conscious but still alive states in humans (e.g., coma, anesthesia) represent a way of delineating what states and aspects are minimally necessary for consciousness to be present.

Phenomenal consciousness, in the way Nagel describes it, is not a simple matter. It entails what we might refer to as the immediate, present felt experience of an entity of itself. This is self-awareness of a sort, but until we can converse with a bat, we will be hard pressed to say it is reflexive self-awareness- the first person observer engaged in observing itself, or, roughly, ‘What am I like at this moment?‘. All mammals feel pain and hunger, but is there an awareness with any particular individual that they are the thing experiencing the pain or hunger? This reflexive self-awareness is intertwined, but not synonymous with, identity, or the ‘who’ or ‘of whom’ in phenomenal consciousness.

Absent reflexive self-awareness and identity, is an entity still possessed of consciousness?

As with phenomenal consciousness, intelligence is not one simple thing. Intelligence includes routine and novel problem solving, and the various, largely non-conscious cognitive capabilities which permit problem solving, but also purposefulness. Doing something for a reason beyond automatic (or programmed) responses to sensory input, with intention.

Purposeful problem solving entails judgement: the capacity to discriminate worthwhile action to implement intentions from actions that will not serve intentions effectively, and the capacity to determine when intentions are successfully met. (In passing, this in turn implies learning and so memory, which are generally regarded as features of intelligence.)

If we include purposeful problem solving, it would seem problematic to exclude reflexive self-awareness and identity entirely from a workable definition of consciousness.

I happen to view reflexive self-awareness and identity as the sine qua non of human consciousness- it is the individual human, because they are aware of their choices and actions as belonging to them and them alone, that is possessed of consciousness.

Must all conscious entities have this sort of sense of self?

If one were to argue reflexive self-awareness and identity are not necessary for consciousness, how do we distinguish this other kind of consciousness from automatic, programmed responses?

Are we in agreement that the term consciousness includes features which necessarily distinguish it from automatic, programmed responses?

Why do you say, in such a blanket way, that AI “lacks sensorium entirely”? That seems plausibly accurate for things like large language models, and recommendation algorithms, but I would have thought that it’s very plausible that embodied and embedded AIs like self-driving cars, and the Boston Dynamics robot dogs, have a sensorium (even if lidar turns out to be a more radically different sensory modality from any of ours than things like bat echolocation and shark electroreception).

“First, we adopt computational functionalism, the claim that the thing our brains (and bodies) do to make us conscious is a computational thing—otherwise, there isn’t much point in asking about AI consciousness.”

Maybe, but it’s an open question whether AI would need to engage in analog (rather than digital) computation to carry out the right kinds of functions—and there are at least some reasons to think that digital computations may be incapable of realizing coherent macroconsciousness.

https://philpapers.org/rec/ARVPAA

Thanks Marcus, I’m a fan of that paper of yours and Corey Maley’s, it’s neat! Analog computation raises some really interesting questions here, as does panpsychism. As far as our methodology is concerned, we do intend to include “analog computational functionalism” (along with Piccinini and Bahar’s “generic computational functionalism”) as species of computational functionalism worth considering. So as we think about how to expand the indicator checklist, we’re open to proposals for indicators that preclude digital computational functionalism: maybe there are some that come from real-time computing constraints, or from constraints on solving tricky differential equations that have no analytic solutions. But there are subtleties here: if the computation in question can be run or approximated on a digital device, then the fact that the neural computation is analog is better viewed as a fact about the implementation than about the algorithm (as we say on page 13 of the report). It also isn’t obvious how much of a setback constraints like this would be for the time horizon of (coherent) AI consciousness, if all that follows from an analog indicator is that we have to run the algo on a spiking net, or something like that.

I have only skimmed the study itself, so my main exposure here is only this nicely written blog post. But I have some immediate methodological worries concerning the way the “Theory-heavy” methodology is implemented.

The methodology as described in the post involves: (1) starting with some extant theories that don’t command widespread agreement. (It’s also not obvious that they all represent theories of phenomenal consciousness at all, though that’s an aside); (2) creating a list consisting in the union of indicators suggested separately by each theory; (3) taking the presence of each indicator to be evidence in favor of consciousness.

But there are some immediate worries about this approach. For one thing, (1) means we have to worry about the possibility that all of the theories are false, and they might not be particularly close to being true. Finding indicators from 5 false (and not even approximately true) theories is not going to tell us much. More worrisome are (2) and (3). The method here ignores the possibility that the presence of an indicator might be evidence for the proposition that *a system is conscious, given theory T1 is true*, while overall being evidence against the claim that *the system is conscious*. I take it there is serious risk of this because the theories being discussed are, at least in some cases, competitor accounts of the same instances of consciousness.

Maybe the authors can alleviate my worries.

Hi Will,

Thanks for voicing those concerns! Ad 1), well, we’re trying to cast the net wide, and we totally agree that our list of theories, and of indicators, is incomplete. Still, even if no one theory enjoys “widespread agreement”, we think that there’s a pretty significant marketshare between all of the theories we consider. And as we explain, certainty isn’t the target, likewise, neither is pleasing all the people all the time. But we hope to please as many as we can! Ad 2+3): good point that we should think about counter-indicators as well as indicators, and consider the hypothesis that one theory’s indicators may be another theory’s counterindicators. But it may be helpful to distinguish here between creature consciousness and state consciousness. Our indicators are indicators that a system has what it takes to give rise to conscious states. As such they don’t counterindicate one another (at least insofar as we agree that humans satisfy all the indicators). On the other hand, the question “which specific states of a conscious system are the conscious states” is more vexed, and here theories on our list can and do disagree. But that question isn’t our focus in the report.

“What It’s Like to be a Smartphone”

https://www.roughtype.com/?p=8528

It’s becoming clear that with all the brain and consciousness theories out there, the proof will be in the pudding. By this I mean, can any particular theory be used to create a human adult level conscious machine. My bet is on the late Gerald Edelman’s Extended Theory of Neuronal Group Selection. The lead group in robotics based on this theory is the Neurorobotics Lab at UC at Irvine. Dr. Edelman distinguished between primary consciousness, which came first in evolution, and that humans share with other conscious animals, and higher order consciousness, which came to only humans with the acquisition of language. A machine with only primary consciousness will probably have to come first.

What I find special about the TNGS is the Darwin series of automata created at the Neurosciences Institute by Dr. Edelman and his colleagues in the 1990’s and 2000’s. These machines perform in the real world, not in a restricted simulated world, and display convincing physical behavior indicative of higher psychological functions necessary for consciousness, such as perceptual categorization, memory, and learning. They are based on realistic models of the parts of the biological brain that the theory claims subserve these functions. The extended TNGS allows for the emergence of consciousness based only on further evolutionary development of the brain areas responsible for these functions, in a parsimonious way. No other research I’ve encountered is anywhere near as convincing.

I post because on almost every video and article about the brain and consciousness that I encounter, the attitude seems to be that we still know next to nothing about how the brain and consciousness work; that there’s lots of data but no unifying theory. I believe the extended TNGS is that theory. My motivation is to keep that theory in front of the public. And obviously, I consider it the route to a truly conscious machine, primary and higher-order.

My advice to people who want to create a conscious machine is to seriously ground themselves in the extended TNGS and the Darwin automata first, and proceed from there, by applying to Jeff Krichmar’s lab at UC Irvine, possibly. Dr. Edelman’s roadmap to a conscious machine is at https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.10461

I have, I think, somewhat above average sympathy with Edelman’s views for a philosopher (though I am not a philosopher of mind), but please, Grant, stop pasting this exact same thing over and over in any post that has anyhting to do with consciousness. It’s gone well past the point of being spam by now. If you want to push an Edelman style view, write something new that is relevant and specific to the particular post or question.

The majority of the replies to my comment over the last several years indicate most people have never heard of the TNGS.

Wait, you have been posting this exact comment across the internet for several years? (A cursory Googling found it word-for-word at least back to May 2018 – among a great many word-for-word identical posts.) This almost seems more like a religious obligation than an academic endeavor.

It is. My hope is that immortal conscious machines could achieve great things with science and technology, like defeating aging and death in humans, because they wouldn’t lose their knowledge and experience through death, like humans do (unless they’re physically destroyed, of course).

I think the majority of replies to your comment are complaints about spam—if the comment is acknowledged at all. But even if the majority of replies are as you describe, who cares? Can’t you see that it just turns most people off, is rarely relevant to the post, and comes off as boring and uncritical? Why not just write a new comment about how Edelman’s theory applies directly to the post at hand? Surely, that would do more to fulfill your “religious obligation” than annoying a bunch of philosophers (who probably aren’t the people you need to convince, by the way).

No, most replies express curiosity about the theory.

Disagreed. But, anyway, see the rest of my comment.

You’ll be happy to know that many of my Youtube posts are getting censored now.

It’s becoming clear that with all your Daily Nous and YouTube comments still out there, the proof will be in the pudding.

if you start with a false premise “computational functionalism” you can prove many interesting things. There is a simple truth (to me anyway) Semantics is not syntax. You cannot build intrinsic qualities (e.g. intentional conscious states and phenomenal “feels”) out of relational states. Maybe someone has demonstrated how this is possible, but i have not seen it.. (seems like it is rather a presuposition required to make sense of reductionist mechanistic theories of mind.

Hi Gordon, even if you are a dualist or a panpsychist, you’ll want psychophysical laws for the conditions under which physical beings are phenomenally conscious. These laws could be couched in terms of computational functions: that would be a version of computational functionalism. (David Chalmers’ work on Organizational Invariance is a locus classicus here). This is what we mean above when we say that a non-materialist could accept our assumptions. Note that in my reply to Marcus Arvan above, I didn’t say “we set aside your argument because you mentioned panpsychism” (which he does, in the paper he linked to): even panpsychists can be computational functionalists, as long as they think the rules for the consciousness of middle-sized creatures like us are couched in terms of computational functions (though there are some tensions between panpsychism and computational functionalism, as this paper of Miguel Angel Sebastian points out)

Hi Jonathan,

Thanks for the reply. It could be that I got carried away in my interpretation of “computational functionalism” As functionalism is at its core the the thesis that you can understand consciousness in terms of purely relational properties, inputs and outputs and whatever goes on inside-to put it crudely. I understand the thesis to be such functional states are not mere signs or causes of consciouness but that they *constitute *consciousnes*.

I don’t know whether functional states are signs or causes of conscious experience for “middle sized” beings such as ourselves. they could be. I don’t see any compelling reason, other than the popularity of philosophical theories that I see as radically misguided, primarily because they attempt in various ways to do philosophy of mind without giving the greatest possible respect to first person experience, sometimes not giving it any respect at all. But anyway…

You are certainly right that you could have this view:

(1) ultimate reality is constituted by simple atomic minds, minds for whom consciousness is an intrinsic and irreducible feature.

(2) you and me and higher life forms are conscious too, but we are conscious is a different way. Our consciousness is constiitutedby the computational/functional relations that obtain among these atomic minds.

But this violates the spirit of panpsychism if not the letter. Remember that the panpsychist does not start by assuming atomic minds (or cosmic world soul minds, on some varieties of the view) The starting point is our individual conscious experience. it is then argued for various reasons, primarily the incomprehensibility of radical emergence, that to account for our consciousness we need to extend the range of conscious beings to include everything physical..Otherwise at some point in evolutionary history consciousness magically pops into being. So the idea that consciousness as present in complex animals like ourselves is different in kind (rather than degree) from that of the hypothesized atomic minds really defeats the motivation for the view.

but i might be misunderstanding you,

Do any of the people writing in this area hold that being alive is a necessary precondition for consciousness and that, since AI’s are not (and presumably cannot be) alive, they cannot have consciousness? Just curious. I’m not saying this view is correct (though I guess it is what I am tentatively inclined to think). I’m just wondering if people who work in this area ever hold (or even discuss) this view. (I realize, too, that this view shifts some of the mystery from consciousness to life and, in that sense, might be no help. What is it to be alive? I guess I have no super-solid answer to that.)

Hi Billy,

Yes, there are a few ways that a life-mind connection has been explored in the literature. One driving idea is that life can do stuff that is too complicated for a computer to do, and that consciousness requires some of those complications. There are a few ways to develop this thought: on one approach, you’re just saying that biological wetware affords more compute than is available for current digital hardware, and consciousness requires some of that extra compute (note that this is consistent with digital computational functionalism). On another approach, consciousness requires some analog computation that wetware can implement but that digital computers cannot (at all, or under relevant time constraints). That doesn’t contradict computational functionalism but it might contradict digital computational functionalism. Then there are arguments that consciousness involves functions that arent computational (e.g., they are functions in a teleological sense, rather than in the sense of a pattern of simple steps to get from an input to an output), or functions that arent computable (e.g. the Halting problem: cf the Lucas-Penrose argument). Finally there are arguments that consciousness isnt even about function, but instead is about intrinsic nature, in such a way that android functional duplicates of you would not be conscious. As Ive summarized it, none of these things are obviously about life per se, though there are elaborations that make those connections. There is also a phenomenological tradition that talks about the continuity between life and mind.

Thanks, I appreciate you taking the time to answer! I’ll think about this.

Wasn’t Johnny 5 alive?

I think where you want to tollens, some will use the same premise and ponens. If being alive is a necessary precondition for consciousness, then many of these theories of consciousness can be read as giving sufficient conditions for being alive. To me, it’s hard to motivate the idea that life would be an *independent* criterion for consciousness, separate from the functional characterizations – rather, I would think that if life is connected to consciousness, it would be *conceptually* connected in a way that makes the functional characterizations have some strong overlap, so that you couldn’t have something that satisfies the functional characterization of consciousness without also satisfying (most of) the functional characterization of life.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oS0FrhYQQr4

possibilities that I think have been under discussed are consciousness existing in the ai but not being analogous to an animal case in ways we would care about for moral standing. e.g. the a.i. consciousness is not unified or diachronically stable, it’s contents have some form of inversion or are orthogonal to behavior or environment.

Yes, those possibilities certainly merit consideration! The question is, what might count as evidence for them? For that, our hypothesis is that the best place to start is with the scientific theories of consciousness that we find promising (and that are compatible with AI consciousness in general). Some of these theories do allow for consciousness that is not unified or diachronically stable. Of course, maybe those theories of consciousness are all wrong, and the correct theory is one that makes room for novel kinds of non-unified or unstable consciousness. Maybe! But we should begin by gathering evidence that that theory is correct.

thank you. there is some asymmetry in different theoretical schools as to how much these issues are studied.

for example, temporo-spatial theorists have paid more attention to the temporal extension of consciousness:

https://academic.oup.com/nc/article/2021/2/niab011/6224347

perhaps our creedences will need to be updated after such issues are delved into by different schools

(time perception is a morally important property; if the a.i. has consciousness, but subjectively experiences it’s entire existence very very quickly, the way we would experience an hour of time, it might have no moral standing)