The Rigor of Philosophy & the Complexity of the World (guest post)

“Analytic philosophy gradually substitutes an ersatz conception of formalized ‘rigor’ in the stead of the close examination of applicational complexity.”

In the following guest post, Mark Wilson, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy and the History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh, argues that a kind of rigor that helped philosophy serve a valuable role in scientific inquiry has, in a sense, gone wild, tempting philosophers to the fruitless task of trying to understand the world from the armchair.

This is the third in a series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

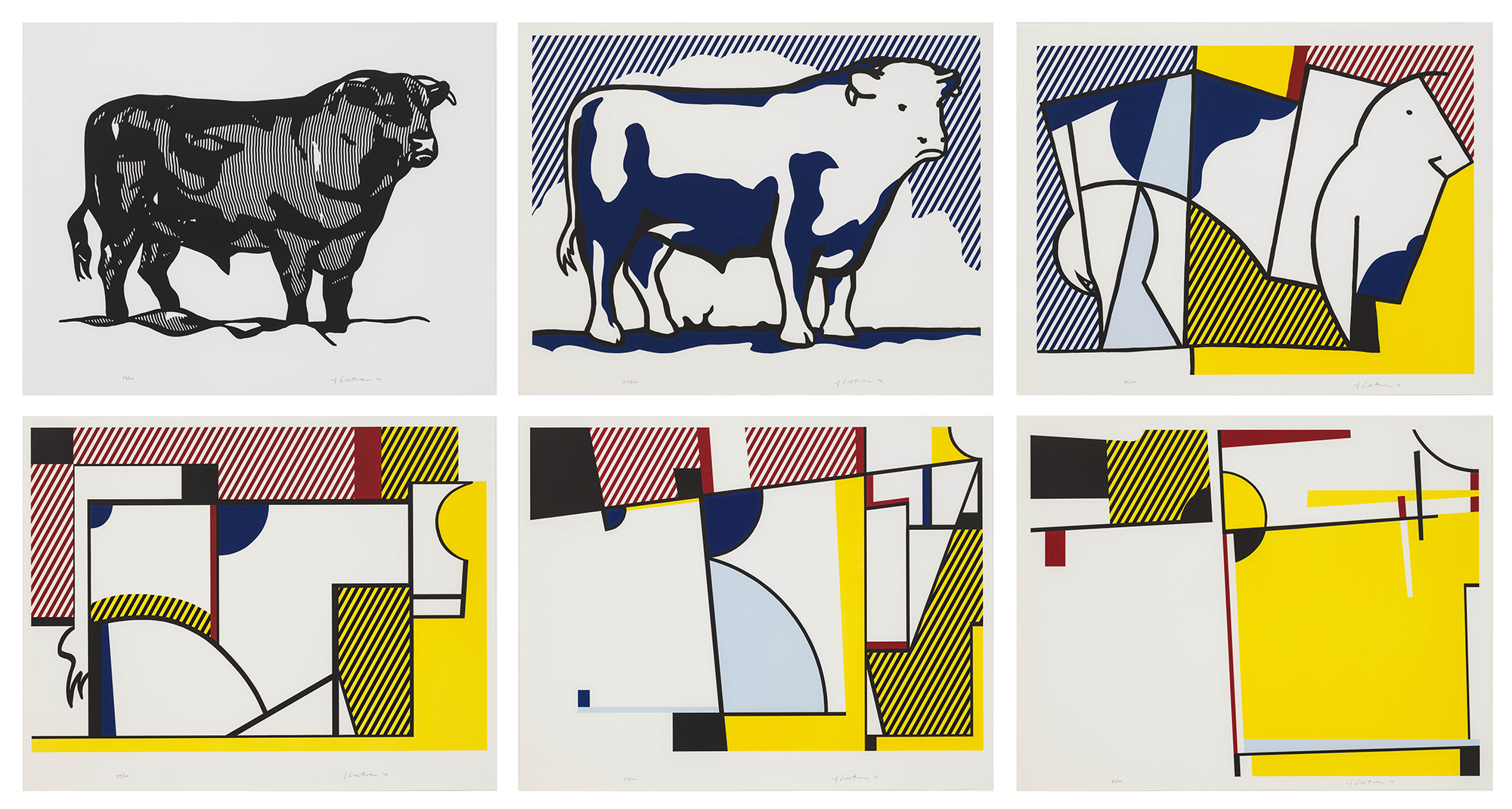

[Roy Lichtenstein, “Bull Profile Series”]

The Rigor of Philosophy & the Complexity of the World

by Mark Wilson

In the course of attempting to correlate some recent advances in effective modeling with venerable issues in the philosophy of science in a new book (Imitation of Rigor), I realized that under the banner of “formal metaphysics,” recent analytic philosophy has forgotten many of the motivational considerations that had originally propelled the movement forward. I have also found that like-minded colleagues have been similarly puzzled by this paradoxical developmental arc. The editor of Daily Nous has kindly invited me to sketch my own diagnosis of the factors responsible for this thematic amnesia, in the hopes that these musings might inspire alternative forms of reflective appraisal.

The Promise of Rigor

Let us return to beginnings. Although the late nineteenth century is often characterized as a staid period intellectually, it actually served as a cauldron of radical reconceptualization within science and mathematics, in which familiar subjects became strongly invigorated through the application of unexpected conceptual adjustments. These transformative innovations were often resisted by the dogmatic metaphysicians of the time on the grounds that the innovations allegedly violated sundry a priori strictures with respect to causation, “substance” and mathematical certainty. In defensive response, physicists and mathematicians eventually determined that they could placate the “howls of the Boeotians” (Gauss) if their novel proposals were accommodated within axiomatic frameworks able to fix precisely how their novel notions should be utilized. The unproblematic “implicit definability” provided within these axiomatic containers should then alleviate any a priori doubts with respect to the coherence of the novel conceptualizations. At the same time, these same scientists realized that explicit formulation within an axiomatic framework can also serve as an effective tool for ferreting out the subtle doctrinal transitions that were tacitly responsible for the substantive crises in rigor that had bedeviled the period.

Pursuant to both objectives, in 1894 the physicist Heinrich Hertz attempted to frame a sophisticated axiomatics to mend the disconnected applicational threads that he correctly identified as compromising the effectiveness of classical mechanics in his time. Unlike his logical positivist successors, Hertz did not dismiss terminologies like “force” and “cause” out of hand as corruptly “metaphysical,” but merely suggested that they represent otherwise useful vocabularies that “have accumulated around themselves more relations than can be completely reconciled with one another” (through these penetrating diagnostic insights, Hertz emerges as the central figure within my book). As long as “force” and “cause” remain encrusted with divergent proclivities of this unacknowledged character, methodological strictures naively founded upon the armchair “intuitions” that we immediately associate with these words are likely to discourage the application of more helpful forms of conceptual innovation through their comparative unfamiliarity.

There is no doubt that parallel developments within symbolic logic sharpened these initial axiomatic inclinations in vital ways that have significantly clarified a wide range of murky conceptual issues within both mathematics and physics. However, as frequently happens with an admired tool, the value of a proposed axiomatization depends entirely upon the skills and insights of the workers who employ it. A superficially formalized housing in itself guarantees nothing. Indeed, the annals of pseudo-science are profusely populated with self-proclaimed geniuses who fancy that they can easily “out-Newton Newton” simply by costuming their ill-considered proposals within the haberdashery of axiomatic presentation (cf., Martin Gardner’s delightful Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science).

Inspired by Hertz and Hilbert, the logical empiricists subsequently decided that the inherent confusions of metaphysical thought could be eliminated once and for all by demanding that any acceptable parcel of scientific theorizing must eventually submit to “regimentation” (Quine’s term) within a first order logical framework, possibly supplemented with a few additional varieties of causal or modal appeal. As just noted, Hertz himself did not regard “force” as inherently “metaphysical” in this same manner, but simply that it comprised a potentially misleading source of intuitions to rely upon in attempting to augur the methodological requirements of an advancing science.

Theory T Syndrome

Over analytic philosophy’s subsequent career, these logical empiricist expectations with respect to axiomatic regimentation gradually solidified into an agglomeration of strictures upon acceptable conceptualization that have allowed philosophers to criticize rival points of view as “unscientific” through their failure to conform to favored patterns of explanatory regimentation. I have labelled these logistical predilections as the “Theory T syndrome” in other writings.

A canonical illustration is provided by the methodological gauntlet that Donald Davidson thrusts before his opponents in “Actions, Reasons and Causes”:

One way we can explain an event is by placing it in the context of its cause; cause and effect form the sort of pattern that explains the effect, in a sense of “explain” that we understand as well as any. If reason and action illustrate a different pattern of explanation, that pattern must be identified.

In my estimation, this passage supplies a classic illustration of Theory T-inspired certitude. In fact, a Hertz-like survey of mechanical practice reveals many natural applications of the term “cause” that fail to conform to Davidson’s methodological reprimands.

As a result, “regimented theory” presumptions of a confident “Theory T” character equip such critics with a formalist reentry ticket that allows armchair speculation to creep back into the philosophical arena with sparse attention to the real life complexities of effective concept employment. Once again we witness the same dependencies upon a limited range of potentially misleading examples (“Johnny’s baseball caused the window to break”), rather than vigorous attempts to unravel the entangled puzzlements that naturally attach to a confusing word like “cause,” occasioned by the same developmental processes that make “force” gather a good deal of moss as it rolls forward through its various modes of practical application. Imitation of Rigor attempts to identify some of the attendant vegetation that likewise attaches to “cause” in a bit more detail.

As a result, a methodological tactic (axiomatic encapsulation) that was originally championed in the spirit of encouraging conceptual diversity eventually develops into a schema that favors methodological complacency with respect to the real life issues of productive concept formation. In doing so, analytic philosophy gradually substitutes an ersatz conception of formalized “rigor” in the stead of the close examination of applicational complexity that distinguishes Hertz’ original investigation of “force”’s puzzling behaviors (an enterprise that I regard as a paragon of philosophical “rigor” operating at its diagnostic best). Such is the lesson from developmental history that I attempted to distill within Imitation of Rigor (whose contents have been ably summarized within a recent review by Katherine Brading in Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews).

But Davidson and Quine scarcely qualified as warm friends of metaphysical endeavor. The modern adherents of “formal metaphysics” have continued to embrace most of their “Theory T” structural expectations while simultaneously rejecting positivist doubts with respect to the conceptual unacceptability of the vocabularies that we naturally employ when we wonder about how the actual composition of the external world relates to the claims that we make about it. I agree that such questions represent legitimate forms of intellectual concern, but their investigation demands a close study of the variegated conceptual instruments that we actually employ within productive science. But “formal metaphysics” typically eschews the spadework required and rests its conclusions upon Theory T -inspired portraits of scientific method.

Indeed, writers such as David Lewis and Ted Sider commonly defend their formal proposals as simply “theories within metaphysics” that organize their favored armchair intuitions in a manner in which temporary infelicities can always be pardoned as useful “idealizations” in the same provisional manner in which classical physics allegedly justifies its temporary appeals to “point masses” (another faulty dictum with respect to actual practice in my opinion).

Philosophy’s Prophetic Telescope

These “Theory T” considerations alone can’t fully explicate the unabashed return to armchair speculation that is characteristic of contemporary effort within “formal metaphysics.” I have subsequently wondered whether an additional factor doesn’t trace to the particular constellation of doctrines that emerged within Hilary Putnam’s writings on “scientific realism” in the 1965-1975 period. Several supplementary themes there coalesce in an unfortunate manner.

(1) If a scientific practice has managed to obtain a non-trivial measure of practical capacity, there must be underlying externalist reasons that support these practices, in the same way that external considerations of environment and canvassing strategy help explicate why honey bees collect pollen in the patterns that they do. (This observation is sometimes called Putnam’s “no miracles argument”).

(2) Richard Boyd subsequently supplemented (1) (and Putnam accepted) with the restrictive dictum that “the terms in a mature scientific theory typically refer,” a developmental claim that strikes me as factually incorrect and supportive of the “natural kinds” doctrines that we should likewise eschew as descriptively inaccurate.

(3) Putnam further aligned his semantic themes with Saul Kripke’s contemporaneous doctrines with respect to modal logic which eventually led to the strong presumption that the “natural kinds” that science will eventually reveal will also carry with them enough “hyperintensional” ingredients to ensure that these future terminologies will find themselves able to reach coherently into whatever “possible worlds” become codified within any ultimate enclosing Theory T (whatever it may prove to be like otherwise). This predictive postulate allows present-day metaphysicians to confidently formulate their structural conclusions with little anxiety that their armchair-inspired proposals run substantive risk of becoming overturned in the scientific future.

Now I regard myself as a “scientific realist” in the vein of (1), but firmly believe that the complexities of real life scientific development should dissuade us from embracing Boyd’s simplistic prophecies with respect to the syntactic arrangements to be anticipated within any future science. Direct inspection shows that worthy forms of descriptive endeavor often derive their utilities from more sophisticated forms of data registration than thesis (2) presumes. I have recently investigated the environmental and strategic considerations that provide classical optics with its astonishing range of predictive and instrumental successes, but the true story of why the word “frequency” functions as such a useful term within these applications demands a far more complicated and nuanced “referential” story than any simple “‘frequency’ refers to X” slogan adequately captures (the same criticism applies to “structural realism” and allied doctrines).

Recent developments within so-called “multiscalar modeling” have likewise demonstrated how the bundle of seemingly “divergent relations” connected with the notion of classical “force” can be more effectively managed by embedding these localized techniques within a more capacious conceptual architecture than Theory T axiomatics anticipates. These modern tactics provide fresh exemplars of novel reconceptualizations in the spirit of the innovations that had originally impressed our philosopher/scientist forebears (Imitation of Rigor examines some of these new techniques in greater detail). I conclude that “maturity” in a science needn’t eventuate in simplistic word-to-world ties but often arrives at more complex varieties of semantic arrangement whose strategic underpinnings can usually be decoded after a considerable expenditure of straightforward scientific examination.

In any case, Putnam’s three supplementary theses, taken in conjunction with the expectations of standard “Theory T thinking” outfits armchair philosophy with a prophetic telescope that allows it to peer into an hypothesized future in which all of the irritating complexities of renormalization, asymptotics and cross-scalar homogenization will have happily vanished from view, having appeared along the way only as evanescent “Galilean idealizations” of little metaphysical import. These futuristic presumptions have convinced contemporary metaphysicians that detailed diagnoses of the sort that Hertz provided can be dismissed with an airy wave of the hand, “The complications to which you point properly belong to epistemology or the philosophy of language, whereas we are only interested in the account of worldly structure that science will eventually reach in the fullness of time.”

Science from the Armchair

Through such tropisms of lofty dismissal, the accumulations of doctrine outlined in this note have facilitated a surprising reversion to armchair demands that closely resemble the constrictive requirements on viable conceptualization against which our historical forebears had originally rebelled. As a result, contemporary discussion within “metaphysics” once again finds itself flooded with a host of extraneous demands upon science with respect to “grounding,” “the best systems account of laws” and much else that doesn’t arise from the direct inspection of practice in Hertz’ admirable manner. As we noted, the scientific community of his time was greatly impressed by the realization that “fresh eyes” can be opened upon a familiar subject (such as Euclidean geometry) through the exploration of alternative sets of conceptual primitives and the manner in which unusual “extension element” supplements can forge unanticipated bridges between topics that had previously seemed disconnected. But I find little acknowledgement of these important tactical considerations within the current literature on “grounding.”

From my own perspective, I have been particularly troubled by the fact that the writers responsible for these revitalized metaphysical endeavors frequently appeal offhandedly to “the models of classical physics” without providing any cogent identification of the axiomatic body that allegedly carves out these “models.” I believe that they have unwisely presumed that “Newtonian physics” must surely exemplify some unspecified but exemplary “Theory T” that can generically illuminate, in spite of its de facto descriptive inadequacies, all of the central metaphysical morals that any future “fundamental physics” will surely instantiate. Through this unfounded confidence in their “classical intuitions,” they ignore Hertz’ warnings with respect to tricky words that “have accumulated around [themselves], more relations than can be completely reconciled amongst themselves.” But if we lose sight of Hertz’s diagnostic cautions, we are likely to return to the venerable realm of armchair expectations that might have likewise appealed to a Robert Boyle or St. Thomas Aquinas.

Discussion welcome.

“In my estimation, this passage supplies a classic illustration of Theory T-inspired certitude. In fact, a Hertz-like survey of mechanical practice reveals many natural applications of the term “cause” that fail to conform to Davidson’s methodological reprimands.”

You seem to be suggesting that there are examples of “cause” and effect for which it’s not true that “cause and effect form the sort of pattern that explains the effect, in a sense of ‘explain’ that we understand as well as any.” Could you provide an example?

Or if I’ve misinterpreted, could you clarify?

I too would be very happy if Wilson provided just a single clear example of the kind of sin that apparently so many analytic metaphysicians are committing every day.

I agree completely. It also doesn’t help that this note is written so poorly that I, at least, found it very hard to figure out just *what* the central criticisms are supposed to be. It’s as if Mark read Steven Pinker’s classic essay on academic writing (https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-academics-stink-at-writing/?sra=true&cid=gen_sign_in) and decided to provide a paradigmatic example of what Pinker was criticizing. At any rate, one useful way to proceed in these comments might be for us to offer up examples, and then try to discern which sins (if any) they are guilty of.

I’ll start: A well-known argument for perdurantism that Sider, Lewis, and Richard Cartwright have all advanced (Sider probably most thoroughly) proceeds from the premise that claims about how many things exists cannot be vague. (Ted: If you’re reading this, maybe you can provide a good summary??) Does this argument manifest some confusion about the proper role of rigor and formalization? (Not a rhetorical question!)

That’s a good start. I’ll follow your lead and use Wilson’s own example:

Davidson’s work, as exemplified in the quotation Wilson chose, uses a conception of causation that has an explanatory requirement: A doesn’t cause B unless A explains B–“in a sense of ‘explain’ that we understand as well as any.” On Wilson’s view, the problem with this is that it pays insufficient “attention to the real life complexities of effective concept employment.”

But is this accurate? Are there real-world complexities which make Davidson’s concept less effective in capturing real-world causation?

Wilson does use the standard scientific realism debate as an example. Although it is not an example from mainstream analytic metaphysics, I think the point is to some extent general. Namely, metaphysicians tend to overly simplify and generalize their target of inquiry by singling out what they consider the most important ontological categories or commitments (in Wilson’s example, it is a “simplistic word-to-world tie“, a kind of correspondence between theory and reality). They then go on to develop sophisticated theories and arguments about that ontological categories or commitments (e.g., truthlikeness), abstracted away from scientific practices.

Maybe I could give another example (not sure Wilson will like it): the idea of (causal) powers or dispositions. There is no doubt that we use dispositional concepts in both daily life and science in understanding the world; they are an indispensable part of our conceptual framework. Metaphysicians, however, believe that they can gain insights into the world by studying these abstract notions without caring about how these concepts are used in scientific practice or a specific context. This leads to a lot of discussions which I personally find not very fruitful.

I still have absolutely no idea what claim is being made. When a realist says ‘electrons are real’, what sin are they committing?

I don’t really understand that either (and am certainly not even a journeyman here never mind an expert) but I do appreciate that in the context of QED (as an effective field theory) the precise nature of this claim is quite a lot more complicated that ‘tables are real’.

“Metaphysicians, however, believe that they can gain insights into the world by studying these abstract notions without caring about how these concepts are used in scientific practice or a specific context. This leads to a lot of discussions which I personally find not very fruitful.”

I think–and I think we should all agree upon reflection–that most metaphysics is bad metaphysics. But so what? Most philosophy is bad philosophy, most science is bad science, etc. The criticism can’t be that metaphysicians do a lot of shyte work, since that is true of everyone!

It seems right that metaphysicians tend to focus their attention on non-scientific examples. But this seems defensible: scientific examples would be difficult for most readers to follow, and if the same dispositional concepts apply in both scientific and non-scientific domains, we should be able to make a lot of progress while focusing on the non-scientific. (Of course, science might provide counterexamples to claims formulated on the basis of non-scientific data. But metaphysicians do “use” science in that way fairly often: relativity is used to raise trouble for presentism, etc.)

I’m less sure that metaphysicians often fail to pay attention to the details of the specific context under consideration. If a metaphysician ignores relevant specific context, won’t another metaphysician write a reply that points out how attention to the context undermines the first metaphysician’s claims?

In my little note, I hadn’t intended to condemn any specific school of philosophy on a generic basis, but merely to complain (under the heading of “ersatz rigor”) of a characteristic valorization of format that seems prevalent today. Long experience in applied mathematics amply warns of dictums that appear plausible when regarded singly but which interact with one another in unexpected ways when assembled as a group. Sometimes these slightly ill-matched ensembles lead to useful applicational conclusions; sometimes not. It often takes a very discerning eye to diagnose the underlying tensions accurately; I regard success in these discriminative endeavors as examples of philosophical inquiry operating at its most admirable level, in whatever subject close attention to delicate detail is required. In Imitation of Rigor, I praise some of Heinrich Hertz’ insights with respect mechanical practice as examples of the critical scrutiny that I admire, but I could have equally cited J.L. Austin’s warnings with respect to “the blinding veil of ease and obviousness that hides the mechanisms of the natural successful act” (in fact, that exact passage is cited on the back cover of my book). But I’ll have to direct you to my book itself for a fuller account of some rather rebarbative details.

More generally, I have become increasingly dismayed by the fact that, under the “blinding veil” of the logistical schematisms that I label as “theory T thinking,” our profession has largely ignored the tremendous body of structural insights that can be found within every modern textbook on differential equations. This complaint lies in the background of my admittedly truncated discussion of Donald Davidson. As I see matters, he has focused upon modeling circumstances that a mathematician will classify as “evolutionary” in character, in which one reaches a temporal conclusion C by marching forward in time from an initial condition I. Working in this vein, we might attempt to explicate the sag of a loaded clothesline by marching forward in time from its moment of first loading I. D-N doctrine in Carl Hempel’s mode suggests that this format can be regarded as paradigmatic of “successful scientific explanation” in general and I believe that Davidson is thinking along similar lines. But from the earliest days of differential equations, applied mathematicians have recognized that such an evolutionary approach is highly prone to deductive and descriptive error and that a more prudent pattern of attack will directly search for the equilibrium state that the clothesline should eventually reach in the fullness of time. And modern practice in the study of differential equations correlates these distinct forms of explanatory approach (viz., evolutionary versus equilibrium) with different subclasses of modeling equation. The general moral we should derive from this accumulated wisdom is that, pace Hempel, not all “laws of nature” operate in the same way within every successful species of explanatory format. Insofar as I can see, these same methodological differences also manifest themselves in how we intuitively talk about causation in the context of our clothesline, for we are likely to declare, “the causal factor that ultimately best explains why the rope doesn’t remain stuck in the unrelaxed configuration C’ is because in that state it hasn’t managed to fully shed the excess internal energy required within a true equilibrium configuration.” Leibniz was fully aware of this distinction; it supports his famous discriminations between “final” and “efficient” causation (for details on both this and the clothesline example itself, please consult another tome of mine entitled Physics Avoidance). Anscombe’s celebrated remarks on human action strike me as falling somewhere within a similar basin of methodological divergence (as my brother George long ago pointed out, contra Davidson, in his The Intentionality of Human Action). Across its full range of real-life employments, “causation” obviously acts as a very tricky word and I would never pretend to have unraveled all of its complicated windings. But I suspect that a bit more attention to the hard-won wisdom of the mathematicians is likely to prove a more profitable exercise than attempting to pilot philosophy’s ship through cloudy waters by relying solely upon highly schematic “neuron diagrams.”

Obviously these considerations reflect complicated linguistic issues that will ultimately involve a fair number of subtle complications. In my note, I was merely attempting to warn against the ersatz rigor promises of “theory T thinking” that outfit armchair philosophy with a blanket rationale for not getting our clothing dirty. In the final analysis, however, murky conceptual behavior ultimately constitutes philosophy’s dedicated metier and we must beware of schematic excuses for evading our duties. All too frequently one nowadays finds analytic metaphysicians dismissing important veins of diagnostic consideration out of hand with an airy “That’s merely epistemology or philosophy of language, whereas I am only interested in the metaphysical issues.” But I don’t believe that our subject properly supports tidy distinctions like that.

“But I suspect that a bit more attention to the hard-won wisdom of the mathematicians is likely to prove a more profitable exercise than attempting to pilot philosophy’s ship through cloudy waters by relying solely upon highly schematic “neuron diagrams.” ”

Indeed: we shouldn’t try to give a philosophically illuminating account of causation by relying *solely* upon highly schematic neuron diagrams. I know of know one working in this area (nowadays, anyway) who would disagree. But maybe I’m in a bubble.

There are a couple papers I know of that argue for something similar to what Wilson has described (except that the formalism they rely on is causal bayes nets, not neuron diagrams):

Gerhard Schurz & Alexander Gebharter’s Causality as a theoretical concept: “We start this paper by arguing that causality should, in analogy with force in Newtonian physics, be understood as a theoretical concept that is not explicated by a single definition, but by the axioms of a theory.”

Wolfgang Spohn’s Bayesian Nets Are All There Is To Causal Dependence: “I argue the behavior of Bayesian nets to be ultimately the defining characteristic of causal dependence.”

Ah. I guess the kind of thing that I took Mark to be criticizing is more narrow. Something like this: We come up with a ton of cases all depicted using neuron diagrams, and consult our intuitive judgments about what causes what in them. We then try to come of with an account of causation that accurately tracks these judgments, and perhaps also vindicates other, more general claim about causation that we find intuitive (e.g., that causation is transitive). And that’s *it*. (Hence the “solely”.) *That* was the methodology that I thought had fallen by the wayside by now. But Mark’s criticisms may be intended to apply much more broadly.

Ned, how would you characterize the dominant methodology employed by people doing metaphysics/metaphysics-adjacent work in causation? Maybe more tractably, what do you see as the major departures of that methodology from the one you characterize as having fallen by the wayside?

I don’t think there’s a dominant methodology, but at least in the corner of the phil-o-causation universe I inhabit I’m seeing more and more interest in approaches that look carefully at our intuitive judgments about cases, try to figure out what’s behind them – what characteristic forms of causal cognition they may exemplify – and try to figure out the ways in which those forms of causal cognition might be valuable for creatures like us, bearing in mind that this last question will depend on the context (scientific, legal, moral, etc.). I think of Jim Woodward’s _Causation With a Human Face_ as an exemplary example and defense of this approach. Again, though, what I don’t see (though maybe I’m too sequestered!) is philosophers just carrying on with a Lewis-style project (as exhibited, say, in “Causation As Influence”).

This was published two years ago in the Philosophical Review:

“…in what follows, I will for the most part confine my attention to some simple ‘neuron systems’ (see section 1 below)—though, along the way, I’ll provide some ‘real world’ cases which exemplify similar causal structures. All of these systems will be deterministic. This narrow focus will allow me to sidestep some thorny questions—for instance, which kinds of variables can be included in a causal model, when a system of equations is correct…”

(https://philpapers.org/go.pl?aid=GALCPA-8)

I think this is the kind of thing Wilson has in mind.

I know that paper well. And it might be an example of the kind of work Mark thinks is mistaken. But, again, it’s not clear why. What Gallow is doing in this paper is part of a larger project of figuring out how best to deploy systems of structural equations as tools for modeling causal structure. More specifically, Gallow is trying to make progress on an outstanding problem for this modeling approach: “… most of the theories developed to date have an awkward consequence: adding or removing an inessential variable from a model will lead these theories to revise their verdicts about whether two variable values are causally related or not.” And he thinks that the best way to solve this problem reveals something interesting about the way we think about causal structure: “…we’ll see reason to think that an adequate theory of causation must distinguish between states which are normal, default, or inertial, and events which are abnormal, deviant departures therefrom.”

On the question of whether my work tries “to pilot philosophy’s ship through cloudy waters by relying solely upon highly schematic ‘neuron diagrams'”, I think the answer is ‘no’, for at least two reasons.

Firstly, because the neuron diagrams I rely on aren’t schematic. By stipulation, they include all of the relevant features of the hypothetical causal system I’m considering. I think I agree with Mark that we shouldn’t use simplistic neuron diagrams as representational tools for more complicated causal systems. I’m in broad agreement with the criticisms of this use of neuron diagrams from Hitchcock’s “What’s Wrong With Neuron Diagrams?“. But I also agree with Hitchcock when he says: “To the extent that we have clear intuitions about what causes what within neural systems, there can be little objection in using them as examples to test or motivate theories of causation.”

Secondly, because I don’t rely solely on intuitions about neuron diagrams, nor solely on intuitions about any other kinds of cases. I think that, in the philosophy of causation, as in most other areas of philosophy, we shouldn’t think of what we’re doing as just fitting theory to the data of intuitions—in part because often we don’t have an unambiguous body of clear intuitions to use as data. Rather, we’re inclined to think about causation in a variety of ways, some of which seem to come into conflict with each other. For instance, we are to some extent inclined to call a ‘double preventer’ a cause, and to some extent inclined to deny that it’s a cause. (Some of us are initially inclined more in one direction or the other, but I think we all have both inclinations to some extent; we all understand what leads others to disagree.) I don’t think we should just plump for one of these inclinations over the other, call it a ‘datum’, and then demand that our theories vindicate it. Part of the task of philosophy is to figure out which of these apparent conflicts are genuine, and, when the conflicts are genuine, which inclination is correct, which is mistaken, and why. My own view is that causation plays its most important roles in our attributions of moral/legal responsibility and in our explanatory practices. So I end up siding with the inclination to say that ‘double preventers’ are causes because I think it’s appropriate to blame and punish a shooter whose gun operates by ‘double prevention’, and it’s appropriate to explain the death of their victim by pointing to the actions of the shooter (cf. Schaffer). Those kinds of choices heavily influence the way I think about causation, and they’re not just appeals to intuitions.

More generally, I’m not sure whether my work is the kind of “ersatz rigor” Mark is criticizing. I certainly wouldn’t mind if it was, but I would like to better understand the criticism. In my work, I often try to simplify things. That’s because I think it’s in general a good methodology to approach a large, difficult problem by starting on simpler, easier versions of the problem. (Of course, you should be aware of the complications even when working on the simplified problem. For instance, knowing that a theory of causation will have to accommodate indeterminism makes certain approaches to the deterministic case less plausible, just because it’s unclear how they would generalize.) Right now, most theories of causation stumble on easy, simple cases, so I think it’s worthwhile to narrow attention to those kinds of cases given our present level of understanding.

Maybe there’s some important insight that I’m missing by not considering more complicated, messy cases. What would help persuade me of that is if someone were to show me important insights about causation that can only be gleaned from the more complicated cases.

Thanks for the clarification. My understanding of your point has improved, but I admit, I don’t have more than a vague impression of it. I suppose I’ll need to read your book to fully appreciate your views.

can you give an example of a philosophical approach that takes into account the messy real world complexity?

If I had titled the essay myself, I might have chosen “The Rigor of Philosophy & the Complexity of Successful Description,” for I believe that closer attention to language is inevitably required in issues of the sort I have cited.

Investigative Ordinary Language Philosophy is such an approach. Essentially the descriptive approach – “Describe language games!” – that Wittgenstein sketches out in PI.

Can’t you write this article for normal human beings? I have a PhD in theoretical physics from the University of Heidelberg and 2 postdocs in renowned universities and have not understood the message at all. It seems to me like just overly-decorated vocabulary that obfuscates the meaning of absolutely every sentence. Either I don’t understand anything about philosophy, or you are using a language that is not related to the common colloquial language. If the former option is the case, then why don’t philosophers engage more in science communication and divulgation. As their science is not at the reach of any external observer.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JamD6wmBI6k