What’s So Bad About “Bad” Philosophy?

In some domains, “overall quality depends on how good the worst stuff is,” while in others, “overall quality depends on how good the best stuff is, and the bad stuff barely matters.”

That is, some areas pose “weak-link problems” and some pose “strong-link problems,” says Adam Mastroianni (Columbia Business School), in a recent piece at his blog, Experimental History.

An example of a weak-link problem is food safety, he says:

You don’t want to eat anything that will kill you. That’s why it makes sense for the Food and Drug Administration to inspect processing plants, to set standards, and to ban dangerous foods. The upside is that, for example, any frozen asparagus you buy can only have “10% by count of spears or pieces infested with 6 or more attached asparagus beetle eggs and/or sacs.” The downside is that you don’t get to eat the supposedly delicious casu marzu, a Sardinian cheese with live maggots inside it.

It would be a big mistake for the FDA to instead focus on making the safest foods safer, or to throw the gates wide open so that we have a marketplace filled with a mix of extremely dangerous and extremely safe foods. In a weak-link problem like this, the right move is to minimize the number of asparagus beetle egg sacs.

One of his examples of a strong-link problem is music:

You listen to the stuff you like the most and ignore the rest. When your favorite band releases a new album, you go “yippee!” When a band you’ve never heard of and wouldn’t like anyway releases a new album, you go…nothing at all, you don’t even know it’s happened…

Because music is a strong-link problem, it would be a big mistake to have an FDA for music.

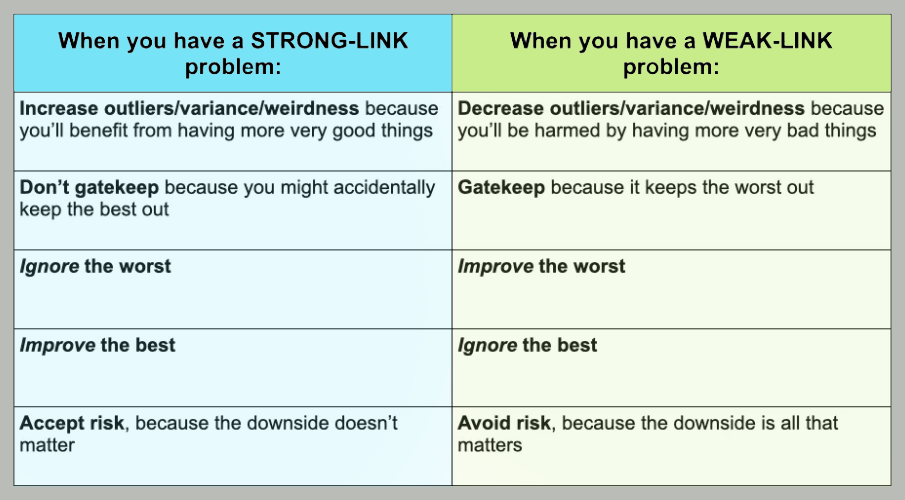

Mastroianni thinks it’s important to know what type of problem one’s facing, because they’re solved differently:

from “Science is a Strong-Link Problem” by Adam Mastroianni

Science, he says is a strong-link problem:

In the long run, the best stuff is basically all that matters, and the bad stuff doesn’t matter at all. The history of science is littered with the skulls of dead theories. No more phlogiston nor phlegm, no more luminiferous ether, no more geocentrism, no more measuring someone’s character by the bumps on their head, no more barnacles magically turning into geese, no more invisible rays shooting out of people’s eyes…

Our current scientific beliefs are not a random mix of the dumbest and smartest ideas from all of human history, and that’s because the smarter ideas stuck around while the dumber ones kind of went nowhere, on average—the hallmark of a strong-link problem.

Yet we tend to treat it like a weak-link problem:

Peer reviewing publications and grant proposals, for example, is a massive weak-link intervention. We spend ~15,000 collective years of effort every year trying to prevent bad research from being published. We force scientists to spend huge chunks of time filling out grant applications—most of which will be unsuccessful—because we want to make sure we aren’t wasting our money.

These policies, like all forms of gatekeeping, are potentially terrific solutions for weak-link problems because they can stamp out the worst research. But they’re terrible solutions for strong-link problems because they can stamp out the best research, too. Reviewers are less likely to greenlight papers and grants if they’re novel, risky, or interdisciplinary. When you’re trying to solve a strong-link problem, this is like swallowing a big lump of kryptonite.

In short, our options for approaching problems often confront us with what we can call the tradeoff between preventing the worst and allowing the best.

Mastroianni doesn’t bring up philosophy in his piece, but we can ask about how this distinction applies to it. We can ask, for instance:

(1) Is philosophy is a weak- or strong-link problem? (Related: maybe philosophy has various tasks, some of which pose weak-link problems and some of which pose strong-link ones?)

There’s some reason to think we treat philosophy as a weak-link problem. After all, philosophy uses peer-review and other forms of gatekeeping. So we should ask:

(2) If we treat philosophy as a weak-link problem, why? What’s so bad about bad philosophy?

(Note: this question is not asking what makes a bad piece of philosophy a bad piece of philosophy; rather, it’s asking: what is or would be bad about having an abundance of bad philosophy around?)

We should also ask about the extent to which philosophical practices actually manifest the tradeoff. After all, the tradeoff is an empirical possibility, not a conceptual necessity. So we can also ask:

(3) To what extent do institutions and practices meant to filter out bad philosophy tend to also filter out or discourage good philosophy?

(4) To what extent do institutions and practices meant to filter out bad philosophy tend to promote or draw attention to good philosophy?

and

(5) Are there alternative institutions and practices for philosophy that could minimize the tradeoff?

Consider, for example, the “collaborative community review” (CCR) (previously “formative peer review“) process employed by the Public Philosophy Journal:

Traditional peer review at academic journals serves a gatekeeping role, determining whether a piece is publishable or not; this decision comes after the piece is nearly complete. This type of peer review practice often proves hostile to new ideas, unproven authors, and unfamiliar audiences…

CCR nurtures new ideas by supporting pieces through their development, creating supportive experiences for authors and audiences. The goal of this review process is to both prepare pieces for publication and improve them in those preparations. CCR is structured to encourage peer engagement rooted in trust and a shared commitment to improving the work through candid and collegial feedback.

You can learn more about the CCR process here. It is just one of many kinds of possible approaches to minimizing the tradeoff, and it would be good to hear about others.

It would be good because there’s some value, at least in principle, to sorting.

Consider an art museum that will accept any artwork, displaying them in a layout that reflects the order in which they were received, and that keeps expanding, building new galleries as its existing ones fill up. There might be a lot of good art here at MegaMuseum, including some good art that might not have ever found a way to be in the public’s eye but for this museum. Still, MegaMuseum is not my model of an ideal museum. After all, life is short, and so is patience. How much time and effort do I want to put into sorting through the works there to find good pieces? I’d rather go to MiniMuseum, which is a much smaller, more carefully-curated museum. It’s more valuable, even if it doesn’t have as much good stuff, and even if not all of the stuff it does have is to my liking.

Of course, if we had to choose between MegaMuseum and MiniMuseum, then it seems that MegaMuseum is the better option, despite the downsides. We might see art, as Mastroianni does, as a “strong-link” problem.

But even better than MegaMuseum would be an enormous array of MiniMuseums, each different in some of the myriad ways museums might differ (eras, media, themes, purposes, standards, intended audiences, etc.). We’d have a better sense of where we ought to go, given our aims, and how to make sense of what we’re presented with—basically how to get more value from our museum-going experiences.

We might think the qualitative and thematic sorting work journals do is valuable in a way that’s analogous to having many and varied art museums. We might also think that such a system has downsides. For example, attention is limited, and so sorting risks directing attention in unequal or elitist ways. Resources, including human labor (referees) are limited, and sorting risks directing them in unequal or elitist ways, too. And so on. Is there a way to capture the good here, and minimize the bad?

Discussion welcome.

(via Marginal Revolution)

Bad philosophy might function like epistemic pollution and make it harder to recognize good philosophy as good even if it’s around. If so, then perhaps philosophy is more of a weak-link case than seems at first. For the same reason, I also wonder if science is more of a weak link case than Mastroianni recognizes.

Epistemic pollution also makes it harder for philosophers to prove to their peers and employers that they’re doing good work. Maybe history will eventually sort the wheat from the chaff, but assistant profs don’t have the luxury of waiting!

I think the best way to think of it is what will likely happen if we let bad X fly. Science cannot be generally said to be only a strong-link problem. Medical science can admit all matter of very harmful quackery, true of many kinds of nutrition science and even some engineering stuff, the tendency of many people to engage in self-researched cures makes these sciences closer to the FDA case than music. However, bad physics, bad chemistry, let it fly, and people will not be calculating trajectories or engineering fertilizers by way of crystals.

I’ll hazard to hypothesize that philosophy is far more a sole strong-link problem if we let it fly. Do any of you worry at all that the quacks who write us their tomes will corrupt the youth? Even now, as a strong-link field, the most harmful thing I’ve seen argued coming out of philosophy is effective altruism, Kershnar on why prefering asians in dating is okay, nonclassical logics, and nominalism about abstracta, and the critics don’t even say these things are unpublishable quackery. Methinks though that these are all rhetorical flourishes. And anyways, the sheer number of auxiliary premises a person has to accept for any piece of philosophy to become harmful is far more substantive than, say, bad nutrition science.

I agree that letting bad philosophy fly may not do a huge amount of harm to the world outside of academia, at least compared to letting bad medical science fly. But I think that letting bad philosophy fly does a lot of harm to the profession of philosophy itself.

In philosophy, often people assess whether an article should be published by whether it substantively engages with work on the same issue that has been published previously. If it disagrees with that work, it is required to meticulously defend that disagreement. This means that making a new contribution to a certain discussion requires working through all the bad work that has been published before. So bad work can exert a really heavy influence on the discussion going forward. It’s not exactly that people have to accept the bad work as true, but the need to carefully engage with it means that often literatures end up spending a lot of attention on careful refutations of bad views, rather than on discussions of the relative merits of better views. (I’m not trying to talk about any specific area of the literature, but I’m sure that most of you can think of something you believe fits this description.) It seems to me pretty hard to “ignore the worst” in philosophy than in other fields.

I guess I think that we should think of philosophy as a relatively weak-link field, in the sense that even a few bad articles being published can have a significantly negative influence insofar as they are difficult to ignore. But I think that in this case, part of the thing that makes it a weak-link field is that we have certain kinds of stringent “gatekeeping” practices. I am not really sure what the solution is, because it’s not clear that relaxing our current gatekeeping practices for the sake of making it easier to ignore the worst is the right tradeoff. But I think maybe some of the way that the problem is framed in Mastroianni’s original post is not quite adequate for philosophy (whatever its merits for thinking about science are). The responses he suggests are appropriate for “strong-link” or “weak-link” fields, respectively, have an big effect on whether philosophy should be considered a strong or weak-link field in the first place. Our decisions about how we should respond to the work being produced affects how negative the influence an individual piece of bad work is.

One large problem with revising the way that we publish is that the way that we publish is tied so closely to how we measure productivity. There are few jobs in philosophy and we compete for those jobs mainly by publishing in venues with high standards.

“There are few jobs in philosophy and we compete for those jobs mainly by publishing in venues with high standards.” The second part of this is false on so many levels it’s hard to know where to begin. First, most community colleges don’t care much about your publication record, or rather they definitely care more about your teaching and publishing falls at or below things like willingness to do committee work. Second, while teaching focused four years care that you publish– they want the people they hire to get tenure– where you publish doesn’t matter much to most of them. Finally, let’s just be honest that the Leiter rank of one’s PhD program matters much more than publishing when it comes to research oriented schools.

The first two points seem plausible (I took Hey Nonny Mouse to have research oriented schools in mind.) I’m skeptical of the third, which doesn’t match my own experience on hiring panels – at the very least I can’t see what would justify the implication in your statement that it would be dishonest to deny it.

Isn’t the point just that, obviously and historically, there is a much stronger correlation between being hired for a good full-time research position and having your Ph.D. from a Lieterrific program than there is between the former and having many good publications, so that a highly plausible explanation of the data is that program matters much more than publishing? Do you find that, when put this way, the point remains doubtful?

If David replied that, obviously and historically, there is a correlation between candidates having other valued application materials (e.g., strong writing sample etc) and having your Ph.D. from a Leiterrific program, would you find that his point remains doubtful?

I doubt that’s the point David had in mind. I’ll leave it to him to say whether it is. But it doesn’t make doubtful Sam Duncan’s third point as I understood and represented it.

Further, I don’t doubt the point you raised. But I don’t believe that’s at odds with Sam Duncan’s point, not even if understood less charitably as the claim that committee members at good programs are biased against applicants from non-Leiterrific programs, because those committee members are less likely to look carefully at application materials for applicants from non-Leiterrific programs.

Off the top of my head I can think of at least two cases where a research focused university hired people with Leiterrific pedigrees who had failed to get tenure at their old jobs because they couldn’t publish *at all* while not even interviewing people I knew who applied and had multiple publications in top 20 journals. Granted those are only two cases but I think they should carry just as much David Wallace’s vague assurance here that hiring committees don’t do this kind of thing.

I didn’t make any such assurance. I stated that I haven’t seen it happen on hiring committees I’ve been on. That’s only an anecdote, of course, just as your “off the top of my head I can think of at least two” is an anecdote.

I don’t particularly object to the idea that your anecdote should carry “at least as much weight” as mine. And if your original comment had been along the lines of “I’m skeptical that publication success rather than PGR rank is the main driver of hiring for research universities: I know of at least two cases where the reverse seems to have been true”, I wouldn’t have objected. But the epistemic confidence of your original comment was much higher than that, to the point of saying that no-one could honestly disagree.

I have not seen that demonstrated from the data; at the least, it isn’t “obviously” implied by it. The problem is that (i) PGR rank correlates quite well with success in publishing in highly ranked journals, and (ii) PhD admission is primarily based on faculty-assessed writing sample quality, which can be expected to correlate quite well with faculty assessment of later writing samples. The strong correlations make it difficult to tease out causation.

If I’ve understood, you’re suggesting that what may be driving the strong correlation between being hired for a good reasearch position and having a Ph.D. from a Leiterrific program is publishing promise. And this possibility makes you doubt Sam Duncan’s point that for getting hired, Ph.D. program matters much more than publishing, because it might instead be that publishing promise–rather than Ph.D. program–matters much more than publishing. This makes sense.

However, it should be noted that an applicant’s program sometimes (often?) influences committee members’ evaluations of writing samples and often influences the quality of the writing samples. These things bolster the idea that program–rather than publishing promise–is the main factor driving the correlations. In the end, I find it difficult to doubt that program matters more than publishing.

All perfectly possible.

Outside the situations I’ve seen personally, it seems to me just very difficult to know – which is why I’m so surprised at how confidently people pronounce on it.

I totally understand. Thanks for the conversation.

For someone’s first hire right out of grad school, yes, there may be a stronger correlation with their PhD program than with their publications so far. But for someone’s first hire out of grad school, everyone accepts that publications so far is just a small sample of what the person will produce during their career. (It would be interesting for someone to measure whether publications in the future few years actually ends up better with hiring than PhD program or with publications in the past few years. Hiring committees are trying to predict the future, and it would be good to know whether they are successfully doing so, or deluding themselves.)

When people are being hired after a few years of postdoc, or being tenured, or being hired as a lateral hire as an established Assistant or Associate or Full professor though, the person’s publication record matters *much* more than where they did their PhD (if anyone even notices that) and probably more than where they are currently employed.

(I have heard of hiring discussions for full professors where the department thought there’s no way we can convince the upper administration to hire this amazing person from X State, despite their field-defining publications, while we can convince the upper administration to hire someone from Harvard/Yale/Princeton/Oxford. But there the problem is in the upper administration, not the department – and it can be easier to convince the upper administration to hire someone from Duke than from Pitt, because of the non-philosophy reputation of those universities.)

This is a pretty US-centric view. There are many countries that have no colleges, only research universities. And people do not care where you got your PhD. People working in those countries must publish a lot and in respected venues to get a job.

If philosophical writing is meant to express and inform beliefs, then this is just the ethics of belief debate misleadingly reintroduced under a new name. I’m curious about the possibility that it isn’t. Does the author think the question of what to write and publish has a different answer than the question of what to affirm/deny/continue inquiring into? This seemed to be controversial in recent history (Tim Williamson comes to mind as someone who would likely think we ought to be convinced of our philosophical theses). Maybe thought on this is shifting.

There’s a whole literature in philosophy of science about whether scientists should believe their claims. I believe that Larry Laudan argued that the epistemic attitude of “pursuing a theory” should be thought of as much weaker than belief, and Bas Van Fraassen argued that the attitude of “acceptance” that is appropriate is very different from belief. There’s a whole literature on the “pessimistic meta-induction” that suggests that *no one* should believe *any* strong scientific claims. I’m pretty convinced by this and think that, while scientists need some sort of good support to publish something, belief itself is probably the wrong attitude (people who have my view here and accept a uniqueness thesis in epistemology would think that *no* scientist should believe almost *anything* they publish, but I’m more permissive).

I think that whatever epistemic status scientific theories have, plenty of philosophical theories are going to have worse epistemic status. Maybe people should believe things that they publish, but if so, it’s because of some sort of expressive role that belief plays, that comes after the fact, and not because I think anyone gives anything like good enough arguments to make belief the unique rational attitude to hold towards a philosophical claim.

I suppose this doesn’t address the fundamental question though of whether it’s bad if there’s bad philosophy being published – it just says that not being good enough to be believed isn’t the relevant question.

I am skeptical of the connection between strong-link/weak-link and gatekeeping.

For instance, even if one grants that music is strong-link, there’s lots of gatekeeping in music as well. Being successful in classical music obviously requires passing through years and years of formal training and through many formal selection processes before one is given opportunities and resources.

Popular music might seem less gatekeep-y, but even there I’m not sure. To be successful in popular music, you need to convince record producers and studios and concert venues and promoters and music critics and TV shows to work with you and to feature your music. Obviously, the way to do this is to make good music and perform that music well so that people will respond well to you, but that’s still gatekeeping.

Now some of this has been upended by the Internet, but that much applies just as well to philosophy. One can just start a blog or a podcast and develop one’s ideas without going through academic venues. And indeed some (e.g., Sam Harris) have chosen to do precisely that.

All these gatekeeping practices emerge because at any given point in time there are limited resources (limited studio time, limited faculty positions, limited grant money), and we need procedures to allocate those resources in a way that maximizes whatever values the participants in these communities care about. And those resource-constraints seem to me independent of whether or not the community is focused on a strong-link goal or a weak-link goal.

Now all this isn’t to say that I think current processes in science and philosophy are anywhere near optimal. For instance, it’s painfully clear that in science, grant-writing processes are huge time-sucks and no one in those communities finds that a valuable use of their time. But the reason to reform grant allocation is because the quality of grant applications are not very well correlated to the quality of the work done and that the amount of time spent writing grants is a serious misallocation of experts’ time and energy. I don’t think it follows simply from the strong-link aspect of scientific theories.

i don’t get it. why the straight-faced assumption that this is a legitimate way to sort the behaviour of a whole field? what gives the guy grounds to extrapolate these sweeping arguments about institutions from a criteria for types that’d fit on a fortune cookie? it’s just something the guy has made up. institutions have reasons for operating as they do; particular circulations, policies, MO’s. their reasons might be bad, self-involved reasons, but you cannot diagnose one by cross-referencing your surface understanding of it with a chart. even if the chart has two whole columns.

Couldn’t there also be “median-link problems,” where overall quality depends on how good the average stuff is? For example, given the press to publish, and to publish more, it is conceivable that bad stuff would crowd out good stuff if there is no gatekeeping at all, whereas excessive gatekeeping also is problematic in its own right; so perhaps academic publishing (science, philosophy, etc.) should be deemed somewhere in the middle, neither strong-link nor weak-link?

I’ll address Justin’s points 2, 3, & 4.

2) I think it’s important to differentiate between philosophy that is A) bad in terms of its quality of thought/argument or familiarity with its field, or prose, and B) philosophy that an anonymous reviewer considers “bad” because it addresses a given problem differently than the way the reviewer thinks it should be addressed, or argues in the face of the reviewer’s view, or is in a different style than the reviewer likes or is used to.

In the case of A, the answer to the question “what’s so bad about bad philosophy?” would be that strong argument and/or rigor and/or due diligence and/or comprehensibility would no longer be the aspiration for philosophers and that can’t be good.

In the case of B, though, in which a reviewer is challenged intellectually or disciplinarily or by the author’s choice of sources (say contintental work rather than analytic work), in which either the reviewer doesn’t make the effort to understand or simply doesn’t like the way the author’s approach or view, there is clearly a problem.

It seems to me that in the humanities writ large, case B is a notable problem. Most of the work humanities do is not objective. This means that reviewers are often at least in part called to be “convinced” or perhaps to think a bit differently than they usually do. Some, not all, academics don’t like to do this. Some, not all, academics hate peer reviewing and intentionally or otherwise use it as a way to vent their ressentiment in being asked to do it (see the comments on Leiter’s April 5th “What if authors could respond to referee reports before the editors make a decision?” post) or as a way to wield disciplinary power. This is of course how we end up with echo chambers and the disincentivizing of “novel, risky, and interdisciplinary” work.

The question to me then is not whether the possible outcome of A is worth putting up with in order to encourage that which is good but also “novel, risky, and/or interdisciplinary,” but instead whether reviewers are–within reason and disciplinary norms–on balance reading papers in good faith or not. If they are and prioritizing innovative work in the same way that many universities are prioritizing “DEI,” then the problem is not really a problem. If they are not, if they believe that their view or approach or tradition is simply the only acceptable one, then we do have a problem.

In reality, it’s a mix of course. I think the humanities in general would do well to follow fewer trends, to prioritize the sense of quality I mentioned in A over what I criticize in B, and frankly to take chances on papers that are interesting, novel, even humanely provocative over the nth iteration or tweaking of the same old stuff. But that’s just me.

This is sort of related to your question of how we should treat philosophy, but I wonder how this might apply to the way we report the news, or even just the way we speak about the truth in general. Lying and ‘fake news’ have significant consequences, so is gatekeeping and treating it as a weak-link problem the best approach? It seems that fact-checking websites, for example, function as way to gatekeep the untruths. But might this have the effect of limiting the information that we report on or have access to?

I don’t think peer review is anything like *gatekeeping*. There are places to circulate philosophy papers that don’t have any gates at all, like PhilArchive. There is no norm against discussing unpublished work in writing, even in publications, especially if that work is available on a ready archive. So I don’t think the *gate* analogy works; there isn’t any sense that things need to be kept ‘outside’ until and unless they get approved.

And it clearly isn’t the point of peer review in top philosophy journals. The vast bulk of papers sent to Phil Review are good enough to publish. The problem is that they are not good enough to publish in Phil Review. (In that respect they resemble most of my work, which has been good enough to publish and not good enough to publish in Phil Review.) Saying a paper isn’t up to Review standards isn’t gatekeeping; it’s saying that they have a page budget that’s about 2% of their submission quantity, and this isn’t in the 2%.

From that perspective, it seems like the existence of things like Phil Review means we’re treating philosophy as a strong link problem. If we’re going to “Improve the Best”, that means we have to identity the best, and that’s hard when there are more papers written each month than any person could read in a lifetime. But a well functioning journal system could be part of the solution. Now whether it is part of the solution is a much harder question, but at least that’s the kind of problem that the journal system we currently have seems designed to solve, unlike the thought that it serves a gatekeeping function.

Bad philosophy, much like good philosophy, is of no concern at all, as it will not be read or influence anyone besides a pool of maybe 5 thousand people world wide.