The Ends and Means of a Graduate Student Conference

A graduate student in philosophy has the responsibility of organizing a graduate student conference hosted by their department, and has some questions, starting with:

1. “Why put on a graduate student conference? What should the purpose of a graduate conference be?“

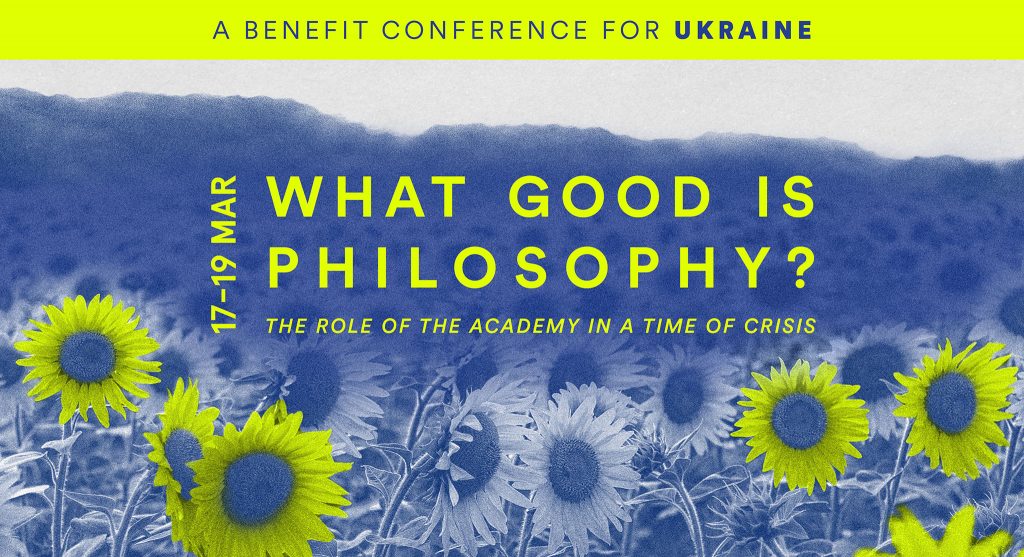

(modification of a photo by Simon C. May)

They write, “One possible answer is that it provides a low stakes opportunity for grad students to practice presenting and commenting. And the student presenters can get valuable feedback on their work.” But the student hase questions about how to address various issues:

2. “I don’t quite know how I should balance the needs and interests of the two main stakeholders: student presenters from other schools and the grad students at our school.”

3. “Which papers should we accept for the conference? The obvious answer is to accept the best papers. But there are competing goals. For example, I want the presenters to benefit from the conference. Our conference will have a (faculty) keynote speaker. So it seems there’s a reason to prioritize papers by graduate students that suggest they’d benefit the most from the keynote speaker’s presence.”

4. “I want to be inclusive of the diverse interests the audience (i.e. grad students at our department) might have. Not everyone is interested in the main theme of the conference, and I’d feel bad having them sit through the whole conference feeling bored. How many of the accepted papers should be ‘off-theme’?”

5. “Should location be taken in the consideration, by preferring students closer to our department since the travel cost would be lower?”

6. “Which parts of the conference do presenters and keynote speaker find the most value in?”

7. “How should I pick the conference theme? How narrow or broad should it be?”

8. “How can I get the grad students in my own department to be more invested in helping with the conference and making it good?”

They add: “In general, I want to hear from people who have attended and/or organized grad conferences. I want to know what they like and dislike about grad conferences, and how such conferences can be made better.”

Readers?

I helped organize my department’s grad conference, and I have traveled to speak at a handful of other grad conferences. Here are some personal opinions on these questions.

I don’t understand why it would be reasonable to take location into consideration. It strikes me as very unfair. Some grad students do happen to have travel funds or can apply for travel funds for things like this. It would be unfair to be rejected because the organizer assumes you won’t be willing to pay to travel so far. I think conferences like that should just say in the CFP that funding is/is not available. But also, I don’t think it’s all that common to decline for that reason, at least not so common (or such a big deal when it does) that organizers should be basing their acceptances on the assumption that this will happen.

Let me suggest that this might not be the best way to think of the problem. It reads as if there is a univocal thing, a “graduate student conference”, and the task is to work out what that thing is for. I think it’s better to start right at the beginning by thinking ‘I’d like to organize a conference to achieve XYZ goals”. So for instance: it might be a good idea to organize a conference on (say) philosophy of mind, aimed at building networking among grad students in that field general, including the subset of your own students who do philosophy of mind – in which case: the theme is obvious; it makes sense to try to find space for those students at your institution who specialize in philosophy of mind to give talks, but most of your talks will be from outsiders; your selection of papers is likely to be curated to get a good overall program. But it might equally be a good idea to have a conference aimed to generally advance the professional skills of grad students in your institution and in your region – in which case, probably there’s no theme, some respectable % of the slots might be reserved for your students, and you’ll probably select papers (within local and regional subgroups) on some generalized measure of merit. And there are other good ideas beyond these. Work out what the point of the conference is, and the rest will then be much easier to work out.

Since the OP asks for input especially from those with experience, I should give mine: I’ve never organized a grad conference nor attended as a student, but I’ve attended as external keynote several times. In each case the conference was themed (philosophy of physics, obviously), was hosted by an institution with a research focus on that theme, but had a substantial fraction of external grad students; my role as I understood it was partly to provide feedback on the participants’ work and partly to facilitate networking between junior approaching-the-job-market people and senior researchers. From that perspective the meetings I attended seemed to work well, and would have worked much less well if there had been no theme: my feedback would have been less informed, and networking with me would have been less useful. But again: that’s just one model, and one set of experiences.

When I was a grad student at Brown, we had an annual conference. I remember that the keynote speaker usually just gave their speech and skipped the rest of the conference. The one exception I recall was that when we had Gilbert Harman as keynote speaker, he attended every single student presentation and asked questions at most. Possibly he was more invested because his daughter was one of the grad student presenters (by coincidence, as I know for certain as I was part of the process of choosing grad student presenters, so I know we were strict about blind evaluation of the submitted papers), but in any event I thought that made the conference unusually good that year. I do not know how to get keynote speakers who are more invested in the conference other than by that kind of luck, but it suggests to me that factors other than the prominence of the speaker should be factors in choosing the keynote speaker.

I think it would a good idea to communicate the expectations you have to the key note upfront as part of the invitation. E.g., “In addition to giving a keynote, we hope [expect] that you will be an active participant in the rest of the conference.”

Alternatively, and maybe less upfront, you can also offer the keynote the opportunity to ask the first question in every talk. That communicates the expectation of participation and will also make it very likely that the key note will ask a question in every talk. Might facilitate the networking after the talk too.

While in various stages of being a grad student I took part in three grad student conferences – one at UT Austin, with a philosophy of biology theme, one at Rutgers/Princeton, w/o a theme, and one at Villanova, focused on philosophy of race. All were good and useful. A few thoughts:

1) In at least the last two cases, grad students from the department(s) were commenters on all of the papers. I thought this worked well. (This might be so for the philosophy of biology conference, but it was so long ago now that I don’t actually remember.)

2) In all of the cases, faculty participation was relatively low (except for some faculty who were directly involved in the planning or the like.) This was mixed – it kept down worries about, say, faculty dominating discussion or “local” grad students trying to show off for their teachers, but it also reduced the value that might have come from meeting more people and getting more input from experienced philosophers. That said, in each case at least one or two senior people at each conference took a real interest and spent time talking with grad students. That was good. My impression is that it will be a better experience if at least a few professors will be willing to take an active part.

3) In each of these cases “local” grad students housed the participants. Sometimes this meant sleeping on someone’s couch or the like. This is of course in some ways less than ideal but helps keep costs down, and I enjoyed getting to know some students in the other departments the times I took advantage of this. (The Villanova conference was one day and just down the road from Penn, so I didn’t bother then.) You might note something like “presenters can be housed with graduate students for the conference if desired” in the info about the conference.

4) If you have no or limited money to offer for travel expenses, make it explicit in the CFP/announcement. I don’t think you should explicitly rule out people who are not local as some may have their own travel funds, but make funding limitations explicit. (Perhaps in borderline cases where funding is limited it might make sense to take someone close by so as to have a bit more money to bring in someone further away, but I’m not sure on this.)

5) Keep in mind that organizing such a thing is likely to be a lot of work, especially if done well, and that the “direct” pay-off (i.e., something that will help you get a job) is likely to be relatively low. That said, the “indirect” pay-off could make it worth it, between getting experience doing such things, meeting people, learning about new work, etc.

Good luck!

Back when I was a grad student, I helped organize a couple of graduate conferences.

Our primary objectives were to network with students from other programs and give our own students professional experience. To this end, all presenters were students from other places, whereas commentators and chairs were current students in my program.

We never had a specific theme – though we’d have a keynote lined up before putting out the CFP, and tended to get proportionately more submissions related to the keynote’s areas of research. To generate interest (i.e. make sure that grad students and faculty would turn up), we tried to put together a balanced program, with papers representing the various areas of strength in our department. We tended not to accept papers that fell outside of those areas – it made more sense to bring in speakers whose work we could really engage with (and who might benefit more from our comments and Q&A).

Submissions were processed through blind review, and we did not consider location when sending out acceptances. Although we could not provide travel funding, we had our graduate students volunteer to host visitors on their couches. We were usually able to get funding to take the speakers and commentators out to one fancy dinner with the keynote. Usually, one of the graduate students would host an off-campus gathering for conference attendees.

I think our conferences were very successful. We received positive feedback from presenters, and we got quite a bit of buy-in from other graduate students in the department. As a graduate student, it was great to gain the experience of reviewing submissions, providing comments, and chairing sessions; best of all, I’m still friends with a few of the graduate students who came to our conferences and are now active members of the profession.

One aspect that hasn’t been mentioned in the comments or by the OP is the length of the slots. I find esp. graduate conferences to be helpful for my own work only if the slots (incl. Q&A) are at the *very* least 45 minutes, 60 minutes is probably a better lower limit, 75-90 is ideal to my mind. Longer slots allow for much better feedback on your work in general, and in the context of a graduate conference it’s great practice for similar talks later on in your career. Shorter presentations can be practiced anytime you present your term paper in a graduate seminar. Also, from what I’ve seen at least, many short presentations is much more exhausting for the audience than 4 or 5 long sessions.

I’ve attended/presented at a few- and helped organize one- grad conference, and I have two main suggestions which apply to conferences in general:

1. Pick a theme that allows for various fields, subfields, and interdisciplinary work to be showcased in a way that won’t gravitate too much around any one style/methodology (eg, “the nature of time”, “religious experience”, would be interesting)- difference/diversity within a big picture topic that *everyone* can care about is good. Insider work is no fun, and an open topic conference makes it questionable whether anyone with actual interest/background in the basic subject of one’s work will be there. (Keeping this point in mind for paper selection is good- avoid papers that rely too heavily on insider knowledge, hyperjargony stuff, etc- ie choose things a general audience can track without much- or any- background in specific literature or terminology, or prepare to let the cricketts lead Q&A if no one specifically was assigned to comment.)

2. Prioritize conference etiquette and designate volunteers to enforce rules and regulate the environment during presentations. I think I speak for everyone when I say I *hate* it when chairs/commenters/MCs are irresponsible or negligent in a way that undermines the goal of the talks, eg by failing to ensure fairness during Q&A (eg by letting a single person dominate and volley their question endlessly while others are waiting), by doing nothing when there is a serious distraction that could be handled (or even creating it themselves- like once when an organizer started noisily taking out garbages in back during the final talk), or basically just failing in general to consider participants’ interests and minimize disturbances and whatnot. I’ve been a victim and witness of such inconsiderateness and it sucks, and can take a lot away from the experience. (Be deliberate about designating a committee chair who is not afraid to take the reins and clearly communicate best practices, expectations, directions, etc., for volunteers, attendees, etc., so things run as smoothly and fairly as possible.)

I want to add a strong ‘no’ to question 5, of whether location should factor into decisions. Unless, that is, the CFP makes it explicit, because otherwise it’s a waste of people’s time working on papers to submit when they’re just going to be rejected for some other reason. (e.g., we invite submissions from grad students in the state of New York — or whatever). But that would be weird and unusual.

If you aren’t covering travel costs, then why does it matter if someone wants to pay for an expensive trip themselves? Plus, the location where someone will be traveling from does not necessarily correspond to the university where they’re a student (maybe they will happen to be visiting a friend who lives nearby). So it seems like the criterion couldn’t be applied equally. If you are covering speakers’ travel, then I recommend, again, not basing acceptances on location, but rather offering a blanket $300 or whatever fits the budget to each speaker to reimburse travel costs – leaving it up to them to decide whether they can afford to pay the difference, if they’re far away.