Multimodal LLMs Are Here (updated)

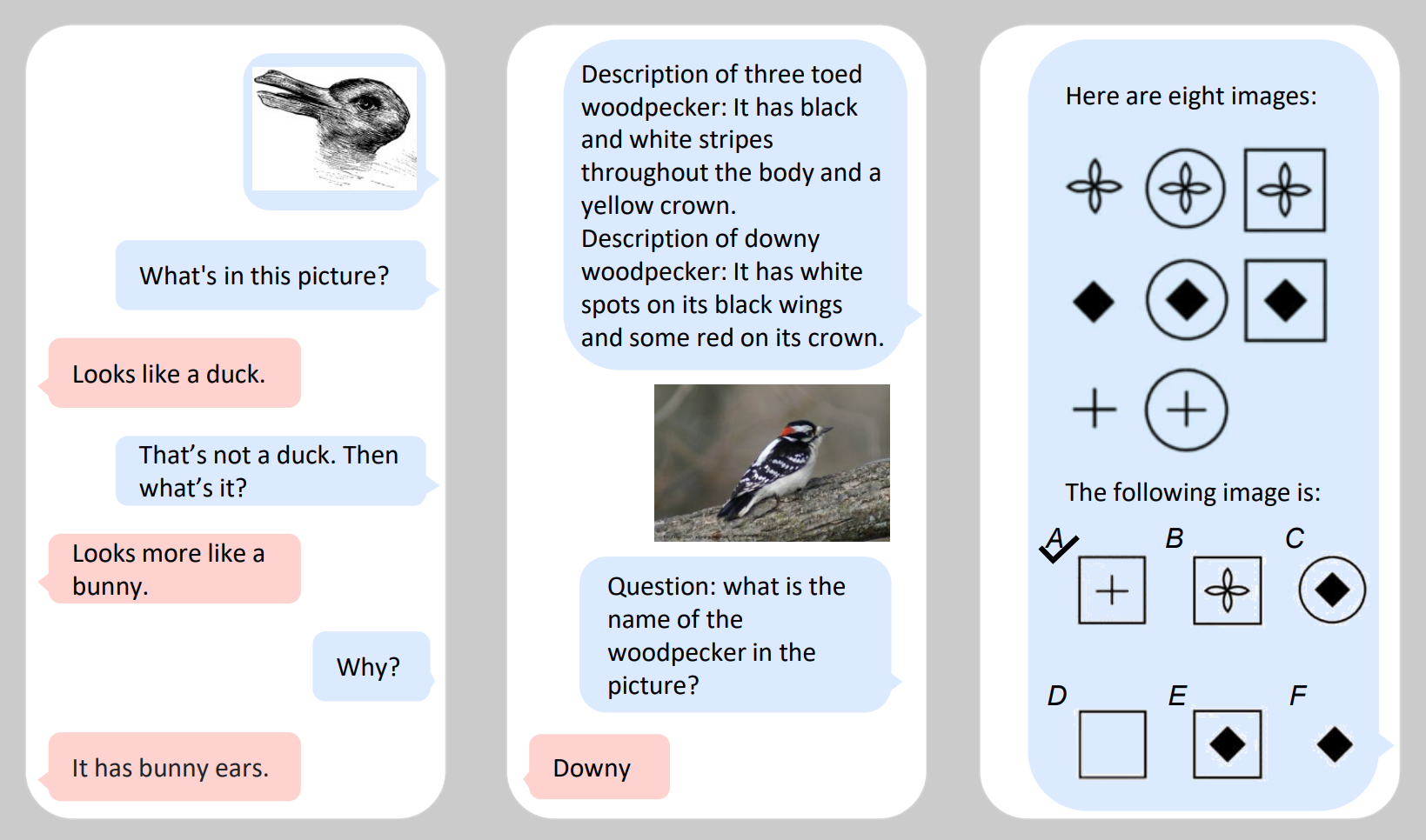

“What’s in this picture?” “Looks like a duck.” “That’s not a duck. Then what’s it?” “Looks more like a bunny.”

Earlier this week, Microsoft revealed Kosmos-1, a large language model “capable of perceiving multimodal input, following instructions, and performing in-context learning for not only language tasks but also multimodal tasks.” Or as Ars Technica put it, it can “analyze images for content, solve visual puzzles, perform visual text recognition, pass visual IQ tests, and understand natural language instructions.”

Researchers at Microsoft provided details about the capabilities of Kosmos-1 in “Language Is Not All You Need: Aligning Perception with Language Models“. It’s impressive. Here’s a sample of exchanges with Kosmos-1:

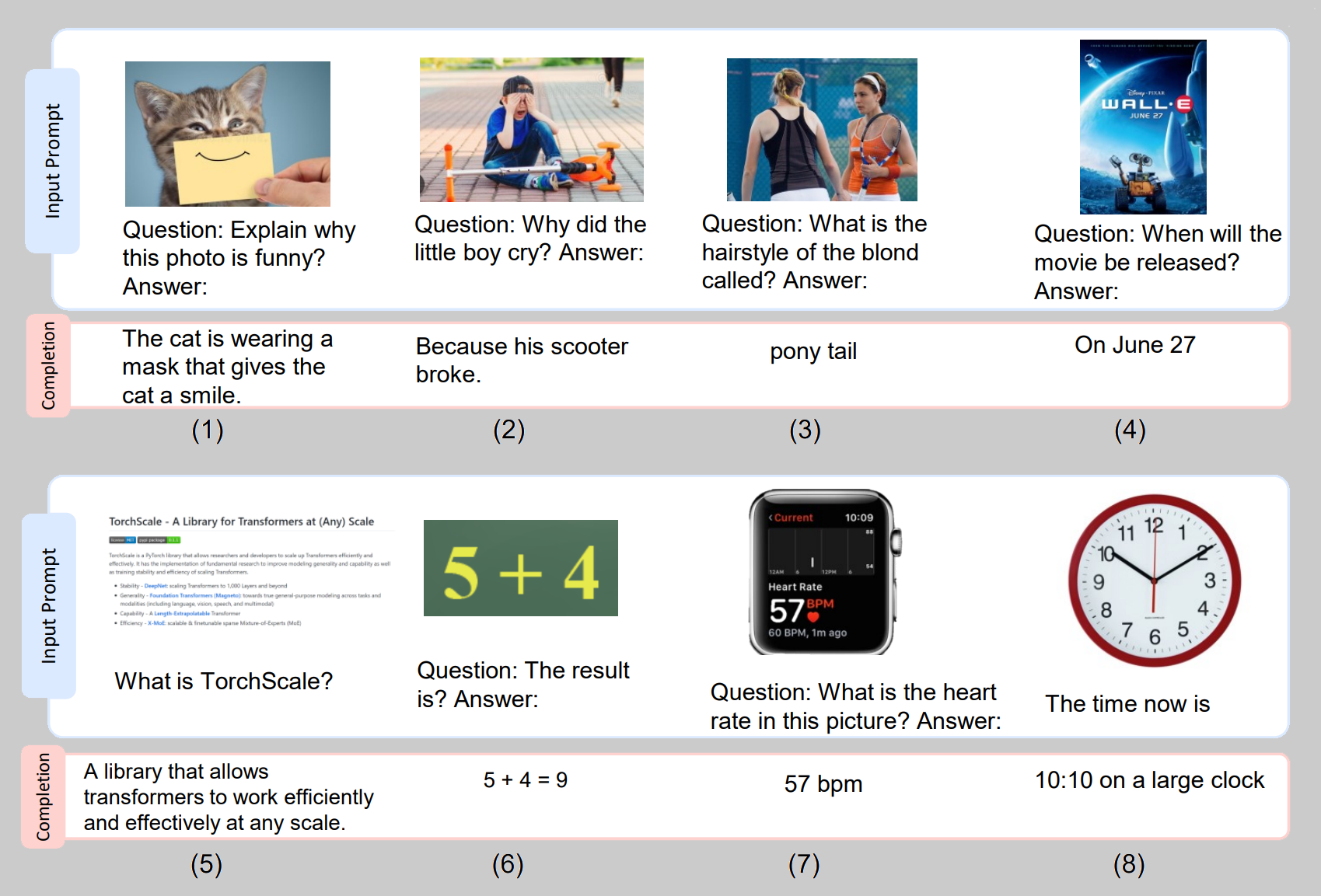

And here are some more:

Selected examples generated from KOSMOS-1. Blue boxes are input prompt and pink boxes are KOSMOS-1 output. The examples include (1)-(2) visual explanation, (3)-(4) visual question answering, (5) web page question answering, (6) simple math equation, and (7)-(8) number recognition.

The researchers write:

Properly handling perception is a necessary step toward artificial general intelligence.

The capability of perceiving multimodal input is critical to LLMs. First, multimodal perception enables LLMs to acquire commonsense knowledge beyond text descriptions. Second, aligning perception with LLMs opens the door to new tasks, such as robotics, and document intelligence. Third, the capability of perception unifies various APIs, as graphical user interfaces are the most natural and unified way to interact with. For example, MLLMs can directly read the screen or extract numbers from receipts. We train the KOSMOS-1 models on web-scale multimodal corpora, which ensures that the model robustly learns from diverse sources. We not only use a large-scale text corpus but also mine high-quality image-caption pairs and arbitrarily interleaved image and text documents from the web.

Their plans for further development of Kosmos-1 include scaling it up in terms of model size and integrating speech capability into it. You can read more about Kosmos-1 here.

Philosophers, I’ve said it before and will say it again: there is a lot to work on here. There are major philosophical questions not just about the technologies themselves (the ones in existence and the ones down the road), but also about their use, and about their effects on our lives, relationships, societies, work, government, etc.

P.S. Just a reminder that quite possibly the stupidest response to this technology is to say something along the lines of, “it’s not conscious/thinking/intelligent, so no big deal.”

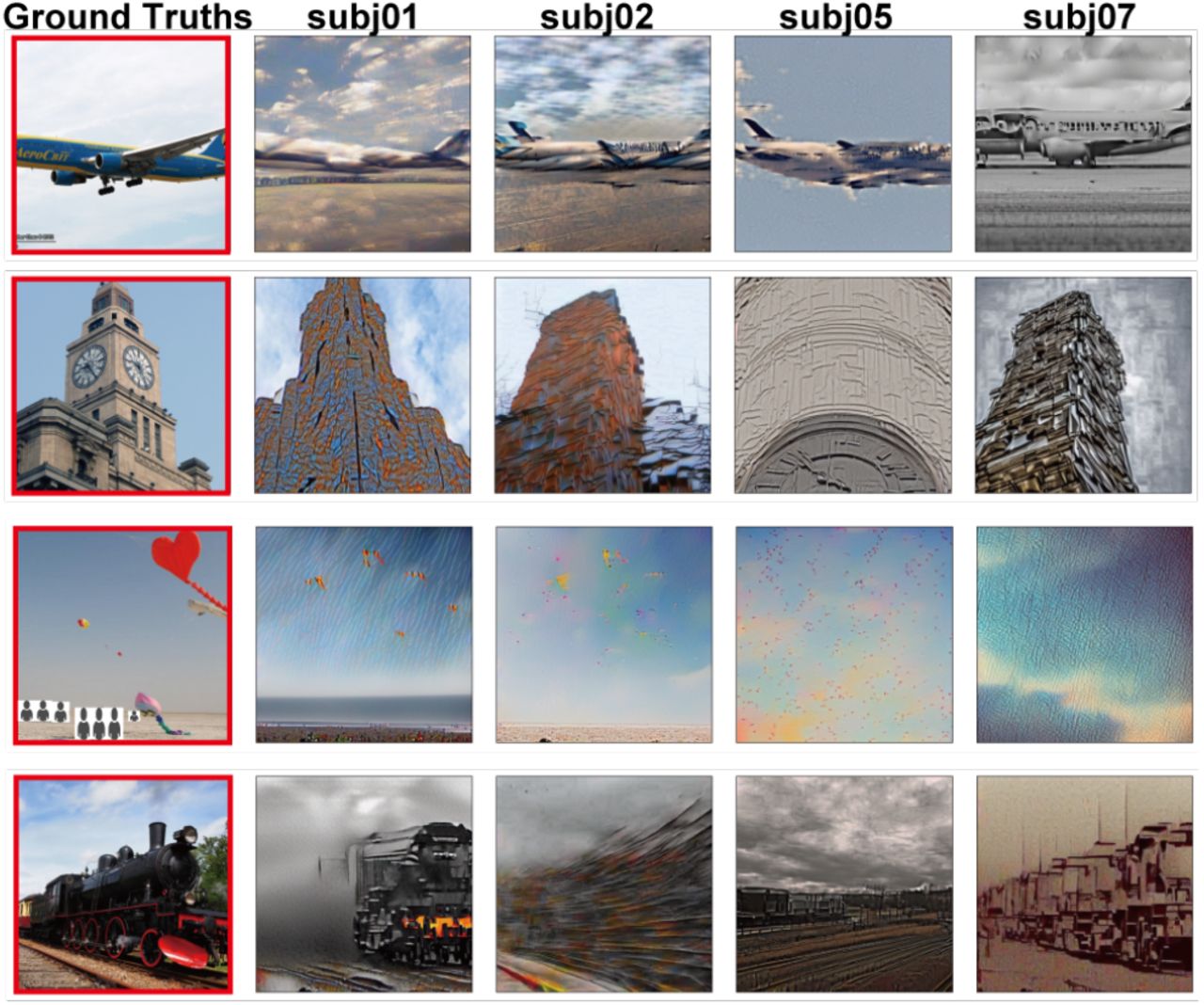

UPDATE (3/3/23): While we’re on the subject of machine “vision,” recently researchers have made advances in machines being able to determine and reconstruct what a human is seeing simply by looking at what’s happening in the person’s brain. Basically, they trained an image-oriented model (the neural network Stable Diffusion) on data obtained by observing what people’s brains are doing as they look at different images—such data included fMRIs of the brains of 4 subjects as they looked at thousands of images, and the images themselves. They then showed the neural network fMRIs that had been excluded from the training set—ones that had been taken while the subjects looked at images that also were excluded from the training set—and had it reconstruct what it thought the person was looking at when the fMRI was taken. Here are some of the results:

The leftmost column is what the four subjects were shown. The remaining four columns are the neural network’s reconstruction of what each of the subjects saw based on their individual fMRIs when doing so.

More details are in the paper: “High-resolution image reconstruction with latent diffusion models from human brain activity“. (via Marginal Revolution)

Thank you Justin for rightly flagging in advance that “possibly the stupidest response to this technology is to say something along the lines of, ‘it’s not conscious/thinking/intelligent, so no big deal.'” Hear, hear.

> ‘it’s not conscious/thinking/intelligent, so no big deal.’

When someone tells me that regarding A.I., I respond with “please prove to me that you are, and in such a way that an A.I. can’t”. That usually shuts them up.

I thought the point of Justin’s “p.s.” was that it’s stupid to think the only thing that matters philosophically is whether AI has phenomenal consciousness, not that it’s stupid to deny that AI has it (which AI obviously doesn’t yet).

Echoing Justin’s nail-hitting remark that there are many important philosophical questions at stake with regards to such machine-learning technologies, their potential uses, and the impact that their use might have on individuals and societies at large. Although recent public conversations about these technologies might seem more like hype and bluster than substance, the technologies in question are going to impact every sector of society in all sorts of ways that are only beginning to receive the widespread attention they deserve. It’s a cluster of topics fully worth attending to.

I wouldn’t go as far to say that it is stupid, but such a response certainly implies a confusion between, on the one hand, the theoretical or conceptual questions, e.g., what it means that X is conscious/thinks/is intelligent, and on the other hand the practical questions that refer to how human beings (should) interact with AI. Obviously, the response implies that, in general, the second set of questions depends on how we answer the first, but there is no good reason for making this assumption.