How Academics Can Make Use of ChatGPT

Much of our talk about ChatGPT has been about students using it to cheat, but there are ways to use it that academics might be interested in trying for themselves.

One interesting set of ChatGPT apps are “readers.” You upload a PDF and then you ask the app questions about it. One of these apps is Filechat. Another is Humata. (There’s also Embra, a ChatGPT-based assistant that integrates into your other apps, such as Chrome; it is in limited beta release, and I have not tried it.) Filechat gives you a certain number of free questions; when you run out, you have the option to buy more. Humata is free, but seems more prone to crashing.

I tried both out on an article I’d been meaning to read, but hadn’t (and still haven’t, alas): “Understanding Philosophy” by Michael Hannon (Nottingham) and James Nguyen (Stockholm), published recently in Inquiry. Of the two, I thought Humata had better answers, but keep in mind this is an n=1 experiment.

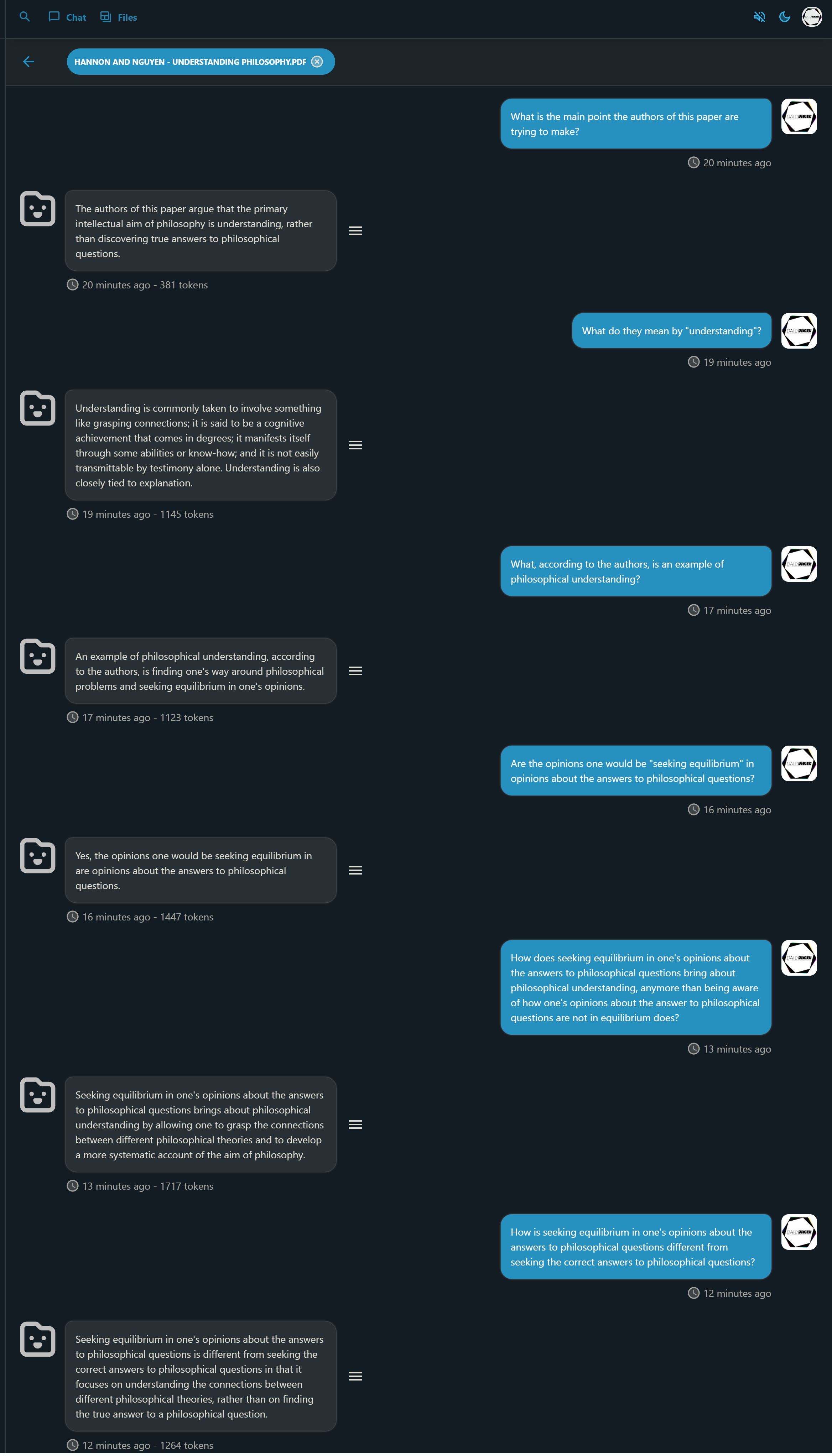

Here is the opening of my exchange about the article with Filechat:

And here’s the beginning of my conversation about the article with Humata:

One of the nice things about Humata is that it provides the page citations that form the basis of its answers, and highlights the corresponding text of the article.

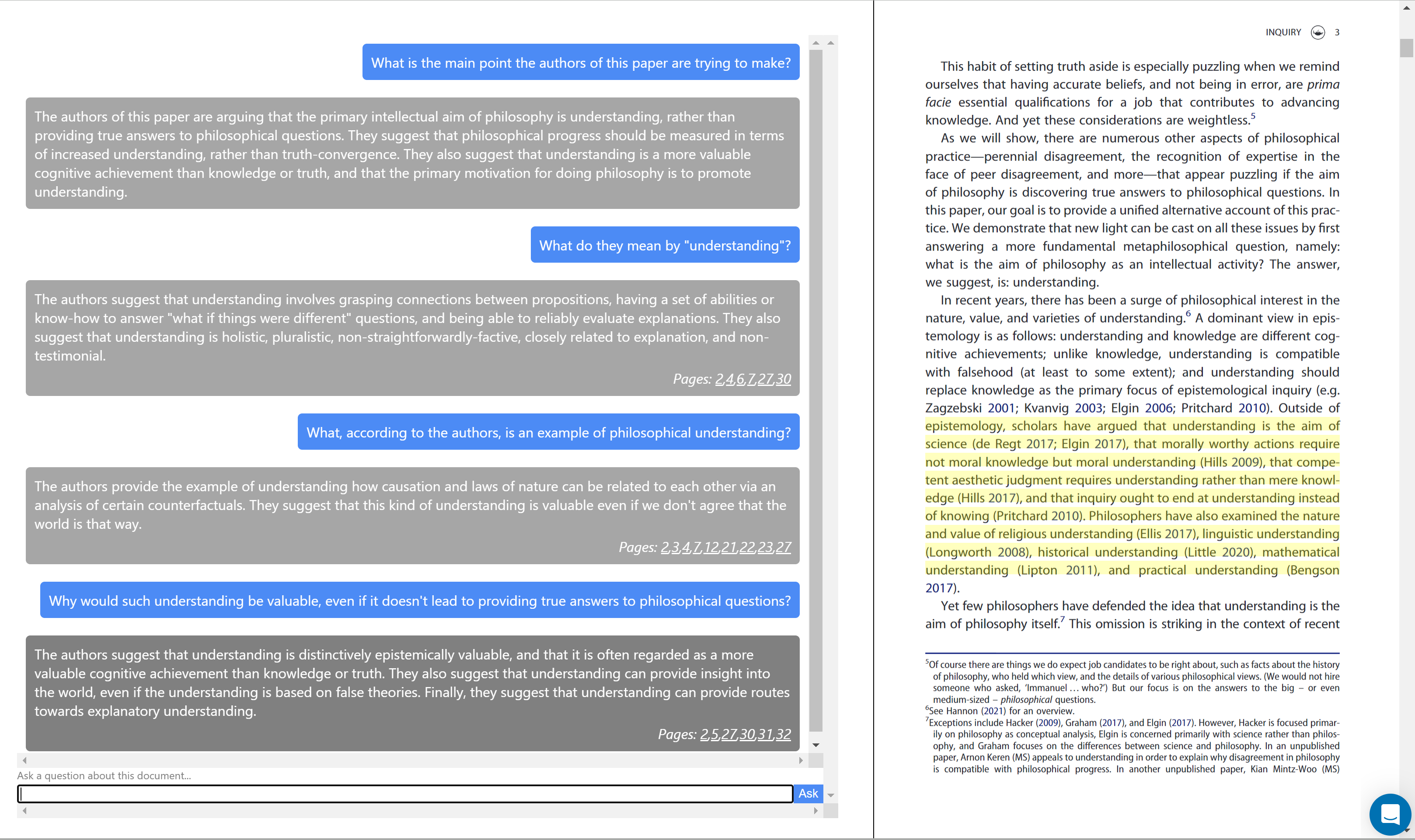

ChatGPT can also work as a preliminary translator. I fed it the opening paragraph of “АНАЛИТИЧЕСКАЯ ФИЛОСОФИЯ, ЭПИСТЕМОЛОГИЯ И ФИЛОСОФИЯ НАУКИ” by В. Н. Карпович, published in the Siberian Journal of Philosophy:

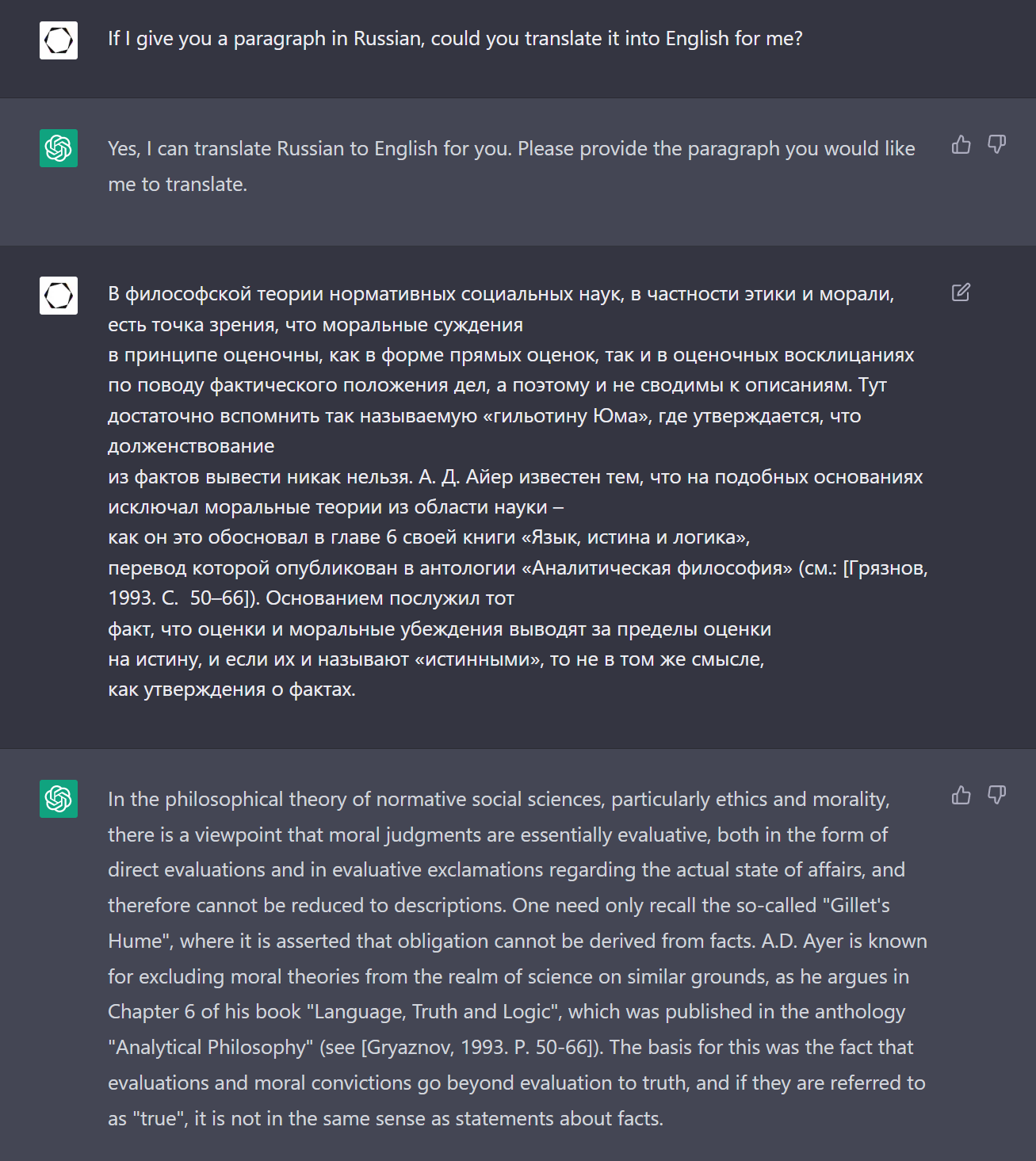

People who need help with writing can ask ChatGPT to, for example, rewrite texts in idiomatic English, or rewrite a text in a simplified manner. This could come in handy in a variety of ways, for example, for teaching complicated texts—particularly for scholars who are self-aware enough to realize that they may unwittingly presume their students understand more than they do. Here is ChatGPT rewriting the first section of the Introduction to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason:

ChatGPT can also handle certain administrative tasks. You could paste in a list of names and have them alphabetized and reformatted, for example, or ask ChatGPT to convert bibliographic entries from one style to another. Or you can have it draft rejection letters.

You can also use it to help finish your sentences. Outline is an online writing app, similar to Google Docs in its collaborative potential, but with ChatGPT built in to help you write. If, for example you’re stuck halfway through a sentence, you can hit a button to bring up the AI, which can help you find the perfect words to finish off your thought. You can also use it to help you come up with new ideas or directions for your text. (I typed the first two and half sentences of this paragraph into Outline, and then asked it for help; it wrote the part in italics.)

When it comes to teaching, several ideas have been floating around, including:

- Feeding ChatGPT or one of the reader apps some text and asking it to generate quiz questions, discussion prompts, etc.

- Asking one of the reader apps which parts of a text are the hardest to understand, so you get a sense of what you might need to put more effort into explaining to your students.

- Asking ChatGPT questions and having your students critique its answers.

I’m sure some readers have come up with or heard other ideas for making use of ChatGPT, other large language models, and AI apps in their work. Please pass them along in the comments.

Fair enough. But, what is the rationale for this classroom/academic use of ChatGPT? Is it “If you can’t beat them, join them”? If so, then that seems to incentivize Big Tech into concluding: “If you make sure they can’t beat you, then you can be sure they will join you.”

I think the rationale is to save time on menial tasks. This seems to be the motivation for uses like drafting rejection letters, generating quiz questions, or finding the part in the paper where the authors discuss a particular premise or objection. (It’s less clear to me that that would be the motivation for doing things like using Outline or producing translations.)

Personally, I am pretty skeptical that ChatGPT tools will save academics significant amounts of time when it comes to performing the kinds of tasks mentioned here. The time it takes to upload a paper into a “reader” and pose the reader a question is the time it takes to skim the abstract and first page of the paper. I think the same can be said for generating quiz questions, and for some of the other ways I’ve seen it suggested that academics can avail themselves of ChatGPT.

I hope and fervently pray I will never become the kind of person who uses ChatGPT to draft a rejection letter.

I find it pretty disturbing that ‘generating quiz questions’ or generating any form of assessment is considered a menial task that could be fobbed off on AI (to be clear, I’m not assuming you hold this view Julia).

We owe it to students to generate assessments that are effective, fair and thoughtfully generated, not vomited out by a large language model.

I think we owe it to students to generate assessments that are fair and effective, *however* we can best do that. The fact that an assessment was “thoughtfully generated” is no reason to give them a less fair or less effective assessment when a less thoughtfully generated, but more fair and effective, assessment is available.

I tried it to ask for some questions for a final exam last semester in logic. When I try to generate logical sentences to ask for a truth table for, it takes me a while, and I have a few patterns I fall into. When I asked ChatGPT to generate a bunch of them, I could then more quickly look through them and find a few that illustrate interestingly different points.

What you described using ChatGPT is thoughtfully generating questions. You thoughtfully reflected on shortcomings in your usual methods for generating problems, used ChatGPT to create a large number of options, and then thoughtfully selected options that you took to illustrate a sufficiently wide range of points.

To your more general point, I don’t disagree and nothing in my post said or implied that the chief requirement for generating questions is to do so thoughtfully, and certainly not at the expense of effectiveness or fairness.

Questions: Would you rather walk up 10 flights of stairs or use the elevator? Would you rather lift a heavy object with a pulley or on your own? Would you eat a steak with your bare hands and teeth or with a fork and knife? AI like ChatGPT are just tools. Yeah, maybe it’s better to take the stairs sometimes to stay in shape, but why not use a tool if it’s available and effective?

Yesterday was Valentin Karpovich’s birthday. He would have turned 75 years old. Unfortunately, he passed away not too long ago. He would have laughed kindly at the way ChatGPT translates his article.

”Gillet’s Hume” for “Hume’s guillotine” was a bit disconcerting.

Not employed as an academic, but my initial reaction to Outline is that if I ever get to the point where I feel the need to have AI write sentences or parts of sentences for me, then I won’t want to write anything. Period.

What I find fascinating about ChatGPT is the way that it’s help me realize two things about my own writing (and maybe academic writing more generally):

For those on the job market, it can be especially helpful, I think, to either run your own documents through ChatGPT and ask it to improve them (by making the writing more active or direct) or to ask ChatGPT to write the first draft of your cover letters, teaching philosophiese, diversity statements, etc., that you can then modify and tailor to your specific needs. Those who have a talent for asking good prompting proposals for ChatGPT will get much better results with this.

For example. The prompt “Write me a cover letter” will probably spit out a terrible cover letter…but the prompt “Chat GPT can you write me a five paragraph cover letter applying to X position at the university of W? In the first paragraph, officially apply for the position and state my area of specialization in Y. In the second paragraph mention my recents articles (A, B, C) and explain why they make me a good fit for the job. In the third paragraph explain why teaching matters so much to me. Mention my teaching award in 2022…etc etc). In the fourth paragraph mention that I’m especially excited to work with colleagues at the Z center on campus and that I’ve already written public work that overlaps with their interests. Emphasize that work with emotional language.” is definitely going to produce a better first draft than most of us could write.

*You may not see your own writing included in the “we” here and that’s okay. Some academics really do have their own unique writing style or form. In my experience that helps as much as it hurts when it comes working within an adminstrative buearacracy.

I asked ChatGPT: “Tell me what interests you.” The response: “As an artificial intelligence, I don’t have personal interests or preferences in the same way that humans do. However, I am programmed to be interested in learning and acquiring new knowledge, and I am happy to assist users with a wide range of topics and tasks. Is there anything in particular that you would like to know more about or discuss? ” That is a good answer. Although programmed interest is a giveaway. The issue of interest and desire is basic to human and animal intelligence, which no machine can exhibit.

But can ChatGPT be an intelligent conversation partner? Can you turn to it when you’re stuck in a paper – stuck say with a R&R you can’t get your head around? This is what I find most disturbing for us as philosophers. But it might also become the new reality – an artificial thinking partner always there for us.

Hopefully this isn’t too off-topic (it’s certainly not rigorous or anything like that), but:

I suspect that some people, myself included, will always distrust text generators and related tech, no matter how sophisticated, or fair, or comprehensive, or [insert your favorite adjective here] they become. As long as such people are *aware* that they’re interacting with an AI, something will seem off, and perhaps even vaguely foreboding.

I initially found GPT-3 thrilling, and could hardly stop testing out all sorts of whacky text prompts (“recount in dialogue form the famous interaction between Attila and Pope Leo, but replace Leo with Family Guy’s Peter Griffin”—the result was wildly impressive). But, one day, I found an article on GPT and plagiarism, which contained some generated text excerpt on postwar Japanese manufacturing. Even though the excerpt was perfectly written—clear, concise, even stylish—and for all I know factual, I suddenly had the feeling that I was reading nonsense. I really can’t describe it too well (I’ve tried…). The best I can come up with is that it resembled “semantic satiation,” in which you lose the sense of a word’s meaning after quick repetition—but replace “word” with “paragraph.”

It was a really disturbing feeling, and I wonder if anyone has had similar experiences. Maybe I found it disturbing because it suggested, in a really visceral way, that even rationally connected, complete thoughts could be nothing but “dumb” statistical extrapolations (whether from an AI or a human). It’s hard to say. But it seemed… destructive, maybe, to some “special” aspect of humanity, or even just to the feeling of such a thing.

Anyway, that’s a lot of rambling (but I really am curious if others have had weird experiences, phenomenologically speaking, with this stuff). The upshot is my suspicion from above: how much of our hesitation over GPT-3 (etc.) cannot be articulated in the language of reasons/justification, but instead has more to do with feeling (or value, or “humanity”)? Would we be comfortable with a “perfected” chatbot, which controlled for our worries about fairness and fact and the like? I feel like I wouldn’t be, and at least some others wouldn’t be either. Whether that matters is another issue.

or you could teach!

I enjoy taking it through Socratic dialogues – precisely because its views are rather “common”. Taking those arguments back to their premises, showing their weaknesses, and then developing a more interesting line of thought, step by step, can be valuable. ChatGPT is patient, and I have the opportunity to question myself, at times from directions I had not considered.

Thanks for the “readers”! Humata sounds useful.

I just gave Humata a try by feeding it one of our recent papers – and I am actually quite excited: this may be _superbly_ useful. The answers I get (“key points…”, “what exactly do they mean by…”, “how do they support their argument that …”, “what is the connection…”, “are they cherry-picking examples …”, etc.) are not very deep, they misunderstand key points, and don’t realize the more subtle connections and implications. But that reminds me _exactly_ of the kind of responses I have gotten from reviewers over the years. And knowing that is invaluable.

When I write, I write from my own mind. The reviewer and reader do not share this context. Running it through Humata and the like in such a pre-review can show me what actually comes across. And I can adjust.

This is a brilliant use-case.

Roughly two years ago, I and my co-author/collaborator, Caleb Ontiveros, wrote a paper on this topic. It is still under review (ahhh, journals!), but we also posted a brief summary of it on DailyNous in the form of a blog post: https://dailynous.com/2021/07/06/shaping-the-ai-revolution-in-philosophy-guest-post/. We discuss some AI tools in general form that we thought would be useful to many academic philosophers, but we also pointed out that philosophers can play (and should play) a central role in making AI tools more useful for their work. Even if you deny the relevance of all current AI tools for academia and philosophy–a very bold and very implausible view–this is no argument against the relevance of many potential and feasible AI tools that you could help develop. This is the time to get involved, and there are so many opportunities to do so.