Is Any of Analytic Philosophy’s Dominance Owed to McCarthyism?

“It is clear enough that McCarthyism and its legacy were sufficient to make life hard for a particular strand of opposition to the analytic mainstream, characterized by its general adherence to empiricism and liberalism: those who were broadly Marxists.”

So writes Christoph Schuringa a philosopher at Northeastern University London, in an article in Jacobin. He continues:

But its power in cementing the analytic mainstream went beyond this. The whole tendency of the period was to block out alternatives to a paradigm that stretched across disciplines. This paradigm, which consisted of methodologies developed for the purposes of Cold War research and development such as rational choice theory, operations research, and game theory, functioned to reinforce a vision of society, and of inquiry, reliant on the classical liberal idea of the autonomous rational individual as the fundamental unit of society.

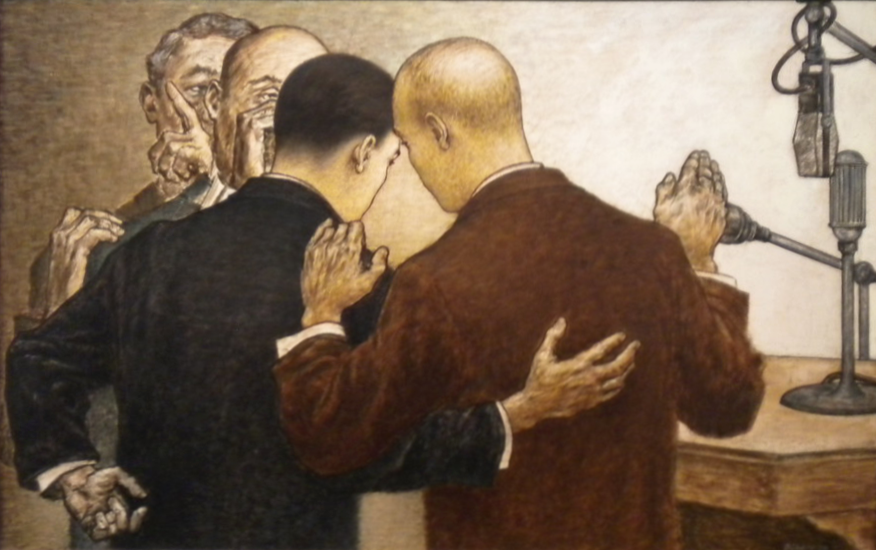

[“Conspiracy” by Edward Biberman]

[Barrows] Dunham made himself into a test case before HUAC by refusing to answer all questions except those concerning his name, age, and address, and then invoking the Fifth Amendment (which protects against self-incrimination). He was duly fired by Temple University. In the wake of this, previous support for Dunham quickly ebbed away. Perhaps the most famous American pragmatist philosopher, John Dewey, had enthusiastically endorsed Dunham’s Marxist work of intellectual history Man Against Myth when it was sent to him at proof stage. Prior to its publication, Dewey became aware that Dunham was in trouble with Red-hunters. All of a sudden Dewey could not remember having ever given his endorsement and withdrew it. Dunham was not restored to his position at Temple until 1981.

Schuringa says that these examples of careers suppressed or derailed by McCarthyism show that “a direct counterforce to analytic philosophy was severely injured in its efficacy.” That “direct counterforce” is Marxism. How different would mainstream philosophy in the United States look had there not been government persecution of people with communist sympathies (and people who had sympathy for people with communist sympathies)? Schuringa appears to think “very different,” but it is of course hard to say. He is currently writing a book, A Social History of Analytic Philosophy, where, perhaps, the case for government’s influence over the character of analytic philosophy, especially its mid-century apoliticism, is made more compellingly. As for this article, I think readers will find Schuringa’s account of the politics of analytic philosophy overly simplistic and monolithic. And he is just wrong in characterizing Rawls’s A Theory of Justice as “an extended apologia for American liberalism.”

Yet the research program of looking at how forces outside of philosophy affect philosophy—its methods, subject matter, ideas, the expectations of its practitioners—is a valuable one, and the questions such influences raise for philosophers’ sense of what they’re up to are worth asking.

You can read the whole article here. Discussion welcome.

John McCumber’s books on this topic (The Philosophy Scare and Time in the Ditch) are great, as well as the portions of Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man dealing with analytic philosophy. I am looking forward to reading Schuringa’s book!

Marcuse’s discussions of analytic philosophy in _One Dimensional Man_ are not good. They are not good in many ways, some of which are nicely captured by Alasdair MacIntyre’s book on Marcuse, but also in other ways. (Importantly, MacIntryre himself wasn’t very sympathetic to the people Marcuse criticizes, but nicely shows how the criticisms are just bad.)

In what ways do you find Marcuse’s discussions of analytic philosophy to be “not good” and “bad?” Your comment doesn’t give us much to go on, and it seems Daily Nous readers are pretty evenly divided on this if the number of likes on your and Sorgenkind’s comments are anything to go on.

It’s clear that Marcus just flatly doesn’t undestand the philosophers he’s talking about, and misunderstands modern logic in pretty basic ways. The claims he makes about these philosophers are clear to anyone who has read them, and he assimilates styles and approaches that are importantly different. I’d recommend looking at MacIntryre’s book, if you’re not familiar with the philosophers in question, but if you are, you can read Marcus himself to see he makes a hash of them.

So far from being ‘great’ McCumber’s book Time in the Ditch is a deeply flawed production that borders on the incompetent.. I re-post herewith an earlier critique (which chimes with some of the comments posted below).

McCumber argues that the triumph of the unduly disengaged school of analytic philosophy in the USA was due to McCarthyism. It is a moot point whether analytic philosophy IS unduly disengaged (Russell, Ayer and Hart, for example, were notable as as public intellectuals and one reason that so many logical empiricists had to flee to America was because of the anti-fascist tendencies of their thought) , but whether it is or not, McCarthyism can’t be the chief explanation of its triumph in America since analytic philosophy *also* triumphed in other Anglophone countries where McCarthyism was either muted or non-existent. The book is typical of one of the two ways in which American scholars tend to go astray. Because America is such a big, powerful and important country, they find it hard to keep the rest of the world in focus. As a result they are prone to two opposing errors: seeking a global explanation for what is mainly an American phenomenon or seeking a specifically American explanation for what is a global phenomenon. McCumber gives an American explanation for the triumph of analytic philosophy which is global or at least a pan-Anglophone phenomenon (though one should not forget the triumph of analytic philosophy in countries such as Sweden and Finland). There is the further problem that analytic philosophy had largely triumphed in America BEFORE the political advent of McCarthy whose glory days were from 1950-1954. Now you can get around this difficulty by defining McCarthyism more broadly to encompass the red-baiting anti-radical and anti-Communist hysteria (often with an anti-New Deal agenda) that began in the nineteen-thirties and found institutional expression in the House Un-American Activities Committee which began its sessions in 1938 as well as the its predecessors such as the McCormack-Dickstein Committee whose co-chair, Dickstein, turns out (hilariously) to have been in the pay of the NKVD. But in that case the theory becomes even more bizarre as the most high-profile victim of this kind of proto-McCarthyism was Bertrand Russell, one of the founding fathers of analytical philosophy, who was blocked from a job at CUNY in 1940 because of his social and sexual radicalism and his anti-religious writings, reducing him temporarily, to near destitution. So McCumber’s thesis metamorphoses into the claim that philosophers sought to avoid the fate of Bertrand Russell by philosophizing in the style pioneered by, well, …. Bertrand Russell. Well, that’s not quite right (someone might reply); the point is that the triumph of analytical philosophy is to be explained by the fact that philosophers sought to avoid the fate of Bertrand Russell a) by philosophizing in the style of Bertrand Russell whilst b) *eschewing the public role that Russell had played for so many years as an activist for left-wing causes*. But then it seems that what McCarthyism (in this extended sense) explains is not the triumph of analytic philosophy (which was well on the way by 1940 and which happened elsewhere without the aid of McCarthyism) but the relative silence of left-leaning philosophers on social issues that was characteristic of American philosophy in the forties and fifties. In other words, what McCarthyism explains is not the triumph of analytic philosophy in America but the retreat of those triumphant analytic philosophers to the ‘icy slopes of logic’. (This is confirmed by the fact that in other countries, where McCarthyite tendencies were relatively weak, you get the triumph of analytic philosophy without the retreat to the icy slopes: Russell, Ayer and Hart were all pretty vocal on social issues in the forties, fifties and sixties.) But this is Reisch’s thesis as developed in ‘How the Cold War Transformed the Philosophy of Science’. I have reservations about Reisch’s book but at least it isn’t as obviously silly as McCumber’s

My previous version of this reply didn’t make it into Daily Nous, so i am trying again.

Charles Pigden says that i claim that the triumph of analytical philosophy was “due to” McCarthyism. I never said that. I said that it may have been aided by McCarthyism, and that of all the possible reasons for the triumph, only McCarthyism remained (as of 2000) undiscussed. Read the last paragraph of the book if you don’t believe me.

This misrepresentation occurs in the first sentence of Pigden’s second paragraph. I didn’t read any further.

So what McCumber is claiming is not the strong thesis that the triumph of Analytic Philosophy in America was (largely) due to McCarthyism but the much weaker claim that it may have been aided by McCarthyism. Well, you could have fooled me. Call me a cynic, but I rather suspect to him of insinuating a strong claim but retreating to a weaker one when under threat. But so long as he is willing admit that he has failed (and failed dismally) to prove the strong claim (perhaps because he wasn’t trying to do so) then we can call it quits. But I strongly advise him to read the rest of my post nonetheless. He might learn some valuable methodological lessons. For example if you have an historical phenomenon that occurs in locations A, B, C and D, then it is probably not chiefly due to causal factor that was only significantly operative in location A. And it is at least problematic to suggest that a large collection of people were frightened into engaging in a social practice X by the fear of persecution when the most prominent practitioner of X was conspicuously the victim of just this kind of persecution.

Though it doesn’t originate with the author and is by no means novel, one important claim appearing in the article is undeniable: there was a time when American philosophy was not captured and dominated by a certain style of philosophizing, and then there came a time when it was so captured and dominated, and to explain this by citing the suitability of the approach for “getting things right” or by citing the “force of the ideas” produced by the approach is naïve, if not laughable.

Indeed. Joel Katzav and Krist Vaesen have documented the journal capture that took place at the Journal of Philosophy, Mind, and The Philosophical Review from the interwar period on, shifting those venues away from the pragmatist-inflected pluralism that was common before the middle of the 20th century, to the analytical philosophy that dominates their pages afterward. It’s really pretty eye-opening to see it laid out. Work on the history of analytic philosophy by Greg Frost-Arnold, Kevin J. Harrelson, and Adam Tamas Tuboly is also worth considering on this front.

Thanks for the references!

George Reisch has written a wonderful book on the influence of the Cold War – including McCarthyism – on the Vienna Circle positivists. A certain segment of the positivists, as many know, were committed leftists. But read George’s wonderful book for the full story. He is a master story-teller:

https://www.cambridge.org/dk/academic/subjects/philosophy/philosophy-science/how-cold-war-transformed-philosophy-science-icy-slopes-logic?format=PB&isbn=9780521546898

And don’t miss Reisch’s review of McCumber’s book, especially since it seems that (based on the above essay) Schuringa is closer to McCumber than Reich:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/philosophy-of-science/article/john-mccumber-time-in-the-ditch-american-philosophy-and-the-mccarthy-era-northwestern-university-press-2001-xxiii-213-pp-2995-cloth/46BCFCB3A10C0660B105986C08EFCC20

Philosophy has a huge problem in that in order to “advance”, as other disciplines do, we have to replace old theories and ideas with better ones. But we can’t, in general, prove which theories and ideas are better.

There will always be competing sociological theories and competing historical interpretations of particular events, but no one, as far as I’m aware, claims that the discipline of history has a huge problem because all historians don’t agree, for example, on the precise weights to assign each of the causes of World War I. I’m not sure why philosophy should be held to a different standard in this respect.

Historians as a group have often changed their mind in the light of new evidence. Think of the contributions of archeology.

I’m sure that has sometimes happened, but perhaps more often w.r.t. periods or problems where the evidence is somewhat fragmentary and where a new piece of evidence can thus make a big difference.

The UK, Australia and Canada had no direct equivalent to McCarthy and the House Unamerican Activities Committee, but Analytic philosophy dominated and still dominates Philosophy departments in those countries. Does this suggest that something other than or in addition to McCarthyism explains the dominance of Analytic philosophy?

This is such an obvious (and correct) point that I’m amazed it wasn’t even hinted at it in the original piece.

I’m actually curious about the phenomenon to be explained. Is analytic philosophy more dominant in the US than in these other countries? Its dominant in most elite universities, the Ivies the top state schools etc. But is there a UK/Australia, Canadian equivalent to the very large number of schools we have like Emory, Penn State, a lot of Jesuit unis, Vanderbilt, Memphis etc. etc, that is hard to describe as analytic? I think its fair if the explanandum is, analytic philosophy is dominant in the selective elite institutions in the US, but the comparison is worth considering; maybe the sociological fact that US everything dominated everything in the 20th century?

This is a good point – the explanadum here is not carefully described. In Canada, at least, you have some francophone universities which are perhaps more like (in some ways) some of the “hard to describe as analytic” universities in the US.

For better or for worse, as I recall, McCumber focuses on struggles at the APA level – so the fact that the analytic types won these struggles (at least, according to McCumber), leaves open whether there is a large dissenting, non-analytic minority (with which he’d agree with you).

But also: to do a more careful history of all this, you’d want to explain how/why/to what extend “analytic” philosophy (which itself would need to be more carefully described) increased or decreased in other areas of the world (e.g., Scandinavia etc. )

I have no data here, just my impression (which at best pertains to the UK), but my sense is that analytic philosophy was very dominant in the UK, perhaps more so than in the US. You might describe a handful of departments (Warwick, Sussex, Essex, Roehampton, Middlesex/Kingston) as historically having a non-analytic orientation and maybe one as Thomist (Heythrop College, in the University of London, was a Jesuit institution). And even of that small number, several of these departments have recently closed or come under pressure. That is out of around 100 UK philosophy departments.

On the other hand, there is more diversity in historcially analytic departments since around 2010, as analytic philosophy merges more with other approches and departments diversify. And even Oxford has always had famous philosophers working on existentialism and other bits of non-analytic philosophy.

I wonder to what extent this is due to English having become philosophy’s lingua franca. Add to this the fact that the majority of top-ranked schools and departments are to be found in the United States or the UK, most of which encourage the analytic style, and the current situation doesn’t surprise me. We (the rest of the world) go where the rankings do.

Of course, whether such rankings (should) make a difference and actually point to quality research is another matter.

I don’t know this history at all, so this is just a question, not an argument. Weren’t a number of Vienna Circle philosophers, including Carnap, surveilled by the FBI because they were suspected of left wing sympathies? Carnap’s career never suffered, I guess, but maybe other smaller figures didn’t get jobs? I guess I am asking whether there’s any evidence that e.g. game theorists with leftist sympathies were less likely to suffer from this kind of persecution.

There was a very interesting discussion of precisely this with Liam Kofi Bright on the podcast What’s Left of Philosophy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b2Qp5N6hEg8&ab_channel=What%27sLeftofPhilosophy

Thanks for the reference. I’ll definitely listen to that. There was also an episode of BBC In Our Time on logical positivism a long time ago with Barry Smith, Nancy Cartwright, and Thomas Uebel. They talked about the socialist ideals of the Vienna Circle, if I remember correctly.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b00lbsj3

I am just wondering how this plays into the allegation that McCarthyism is responsible for the analytic orientation of US philosophy.

If I’m not mistaken, John E Roemer (leftist game theorist/economist/political-philosopher) had his career seriously harmed by McCarthyism? I know John Kelley, a leftist mathematician (some readers may know his topology book), was targeted. According to my Dad, my grandpa, a geneticist who got his phd in the 30s was negatively affected at least slightly degree.

That’s at least very seriously misleading about Roemer, and more plauisbly simply wrong. McCarthy was dead by 1957, and Roemer didn’t even finish his undergrad degree until 1966. He did have significant trouble with the administration at Berkely because of being involved in anti-war protests as a graduate student, and left his program for some time to teach high school math, but came back, finished his PhD in economics in 1975, and then had a very successful career (ending at Yale). In these discussions, it’s important to be careful with the facts. I think that most of those making the general claim are very loose with the facts and causal claims in particular, but in this case it’s just wrong.

Apologies. I stand corrected. My other comments are based on memory from years ago and are not necessarily reliable.

It is interesting to me how people on this thread construe the McCarthy era. For starters, Truman instituted the Executive Order allowing suspected Communists in the government to be suspended pending an innocent finding. And the phenomenon of guilt by association made common during this period outlasted McCarthy himself. N.B. the Free Speech Movement at Cal amongst other things. Not myself a philosopher, I am struck by how political theory in the US suffered during the 50s and was revitalized somewhat as an import (via Rawls) from Cambridge and the Lastlett group (Historians btw). As one acknowledge in McCumber’s book, I am not interested in commenting on the main thread here but I think clarification of the tentacles of the McCarthy era continued well into my own undergraduate days which began in 1968. That other countries, such as France and Britain, did not go through this is an indication of their intellectual freedom and self confidence. In the US, intellectual freedom was severely truncated as to range of topics worth pursuing and those declared dangerous. Was political theory one such topic? Ask Sidney Hook.

I agree that “red scares” extended well beyond McCarthy himself. But, if one wants to have a testable hypothesis, it’s important to have a clearly formulated thesis. That’s often not done in these cases. (I don’t think McCumber does it well at all.) There’s a strong tendency to start by saying “McCarthyism”, and when it’s showed that that doesn’t fit the actual cases at all (as with Roemer), to extend out to more and more scenarios. But then, the thesis rapidly becomes vapid – it’s about a feeling, rather than a specific claim that might be examined and tested.

The mention of the UK here is odd, given that it was at least as “dominated” by analytic philosophy as the US, and sooner. So, if that happened despite its greater “intellectual freedom and self confidence”, why is “McCarthyism”, even in the broad sense, needed to explain its rise in the US? Maybe it is needed – but we’d need a lot more care than we get from those making these claims.

There are a couple of issues to which I would like to respond, That political theory/philosophy regrouped in the UK fits my contention that such pursuits were taboo during this era dominated by red-baiting (McCarthy Era, Truman Era, Truman-McCarthy Era). It was dangerous to pursue such ideas in which economic equality might be a goal. Rather it was replaced by the Dan Bell led notion of rising tides. Another example, which reflects a dim memory, is that translations of Weber had the word “Klassen” as group rather than class when Weber used Klassen when he mean class. Later translations done in the 60s corrected that. As I said, this is a memory and I could be in error. The Cambridge Historians Group, including Laslett, Pocock, Oakeshott, and Skinner pushed politics theory without seeming regard to anti-communism as a “grande peur” (Oakeshott was clearly a conservative). In 1956, Laslett’s introduction to the first edition of Philosophy, Politics, and Society, he blamed Logical Positivism for the death of political philosophy. This series, British in nature, Rawls published a key article, “Distributive Justice in the 1971 volume. It was around this time that Marxism in its multiple forms, including the Frankfort School was being taught in US Universities.

Causality is hard to prove. Context is more accessible. US had the red scare and political philosophy was reduced to Hook et al) and other servants of the paranoia.(well documented when it comes to the history of the Congress of Cultural Freedom, US Branch). IN the UK, logical positivism knocked political theory off the rails. Cambridge historians reinvented the history of political theory, brought philosophers like Rawls in and the US conversation was renewed. Rawls was not a marxist but a progressive liberal, not an 18th c. version of liberalism. I would aver that this is the space, which Rawls et al (including Habermas, Marcuse, Adorno, Horkheimer, James, and others filled. And the next generation generated the analytic marxist which was also transatlantic. The rebirth of political theory needed the waning of the red scare to flourish.

It may be that “the rebirth of political theory needed the waning of the red scare to flourish,” but I think it’s hard to disentangle the possible factors. The political upheavals of the ’60s in general probably helped fuel “the rebirth of political theory” (which had never completely disappeared anyway).

Not to weigh in directly on the argument about McCarthyism and its effects, but to make a couple of points about Rawls.

He spent a year at Oxford, where he was influenced by some who were close to the “revisionist” wing of the :Labour Party. (See e.g. Forrester, In the Shadow of Justice, ch.1)

Second, in the ’50s he started working out the ideas that eventually were incorporated in A Theory of Justice. (The article “Justice as Fairness” appeared in 1958, “Distributive Justice” nine years later in the third series of Philosophy, Politics and Society, 1967.) The ideas went through a number of iterations and significant changes, but ToJ had a long gestation period. It also can be seen as using (whether fully successfully or not) some of the approaches or methods of analytic philosophy to address normative questions. So, as is well known, the book reflects more than one stream of influence, including (obviously) the social contract tradition, Kant, and rational choice theory (“on the contract view the theory of justice is part of the theory of rational choice”, p. 47 1st ed.)

How or whether any of this affects the broader argument about the red scare, I’ll leave to others to discuss.

Roemer is too young to have had his career affected by McCarthyism. He was very successful very young and has remained so. His parents were also successful although their careers probably were affected (they were in the CP). His father merited a NYT obit which makes no mention of his communism. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/14/us/milton-roemer-hmo-advocate-dies-at-84.html

To follow up on Justin’s point about Rawls: Schuringa says that “all subsequent analytic political philosophy was conducted” within the Rawlsian framework. Nowhere does he mention analytic Marxism, which began in the 70s. There were also plenty of folks using game theory to think about anarchy, marxism, etc. So it would seem useful, at least, to distinguish “analytic methods” from “analytic content”, at the very least. This also relates to Mohan’s question. Nowadays, “analytic methods” might dominate many US Universities, but most seem to be pluralists when it comes to the “content”…

I’m extremely confused about the dialectic of the piece. The thesis is that the dominance of the analytic approach is explained by the fact that philosophers who pursued alternative approaches were pushed out by McCarthyism. Yet if you look up the examples he gives they’re largely people who’s work seems to fit comfortable within analytic approaches.

*fit comfortably

I’m not saying this is wrong. I’d bet that analytic philosophy’s dominance is the sort of thing that had multiple causes, and many of them had little do with the quality of the work. But I am very skeptical about this narrative since as other readers have pointed out Britain and other Anglophone countries didn’t have anything like McCarthy. The sort of journal capture Katsav and Vaesen describe seems a much better explanation in that I think it probably had much more to do with this. Here are two others that I’d bet were larger factors: 1. Anything and everything German was tainted by the Nazis in the minds of many people after World War II. If a German philosopher could be read as some sort of proto-fascist or even out and out fascist they would be. (Isaiah Berlin built a whole career on this sorry trick). And in the immediate postwar period what we now call “continental” philosophy was almost synonymous with German philosophy. 2. As Louis Menand shows in his “The Free World” pretty much every academic field in the post-war university faced huge pressures to “professionalize” and show that its members were distinguished from mere dilettantes just writing essays and speculating. Part of this was finding a supposed method that its initiates had mastered. He does an excellent job showing how this explains the popularity of say structuralism in literary studies. It seems plausible that this is at least part of how analytic philosophy beat out pragmatism. Analytic philosophy at least claims to have a method while pragmatism is by its very nature opposed to the idea of one true philosophical method.

Louis Menand may do a very good job on the point you mention; unfortunately his 700+-pp. book lacks a strong overall argument or even strong connecting tissue — his contrary claim in the preface notwithstanding — which may contribute to a reader’s stopping at, say, 400 pages in, before even reaching the chapter on academic literary study and structuralism.

P.s. There is some discussion of structuralism, Levi-Strauss, and Jakobson in an earlier chapter, but I don’t think that’s what you were referring to.

Piggy backing on this discussion, but does anyone know any literature on whether (and if to what extent) Confucianism has benefited from political factors?

Which period are we talking about?

I mean, the canonical narrative accepted by Confucians for millennia was that the fall of the Qin dynasty (and its replacement by the Han dynasty) was the reason why Confucianism came to prosper, asserting its superiority over Legalism (even though, in retrospect, it may not be the most historically accurate account).

I don’t read Jacobin all that often, but I haven’t ever read a piece of cultural analysis/intellectual history in it that was better than C work based on argument alone. I understand that they’re writing to an imagined public, so I don’t fault their writers for lack of citation and so forth but essays like this are just completely vapid in my view.

The essentialist claims that anti-essentialist philosophers perennially make about analytic philosophy never seem on point. I doubt very strongly that it has an essence, and I don’t recognize the essence that this author (and other critics of analytic philosophy) identify.

I don’t think analytic philosophy has some special tools for getting things right. It has just struck me that a number of people stopped thinking that writing in Heideggerese and the like was worth it in most cases (even if it can be worth it in some cases). I’m surprised I didn’t see anyone mention this yet in the comments.