Five Years on the Philosophy Job Market

“I have wanted to be a philosophy professor since I first took an Intro to Philosophy course my first semester of undergrad. I have worked tirelessly for 15 years toward this goal. There were so many times when I felt completely defeated, hopeless, on the verge of giving up. There were several occasions when it seemed clear to that it just wasn’t going to happen. I am elated that it has worked out.”

Jeremy V. Davis is currently a tenure-track assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Georgia. It took him five years of applying for academic positions to land that job. His aim in sharing his story is to provide a sense of what it’s like to be on the academic job market for up and coming graduate students. He says:

Five years is not an uncommonly long time on the philosophy job market. I’m not sure of the numbers, but I’d guess it’s pretty close to average—maybe a little on the high side, considering that many people leave for other careers after a few years on the market. Moving around for years, living in relative financial precarity, constantly having to do confusing and time-consuming administrative paperwork in new places, finding new doctors, paying first/last month’s rent before receiving the returned deposit from your previous apartment, wondering whether you’ll ever be able to find longer-term stability in a place, losing and making new friends, and generally just uprooting your entire life (and that of your spouse/partner/family): these are, unfortunately, pretty standard occupational hazards in the field.

But it is not my aim in this post to wax poetic about this journey, what I’ve learned about myself and my profession, and so on. My goal here is rather to illuminate some of the more specific elements of my job search that, in my experience, remain relatively opaque to those who haven’t already experienced it—particularly, graduate students who are planning to enter the profession. In my case, while I knew that finding a job in academia would be hard, I didn’t have a clear enough sense of just how hard it would be—and what, specifically, my own trajectory might look like.

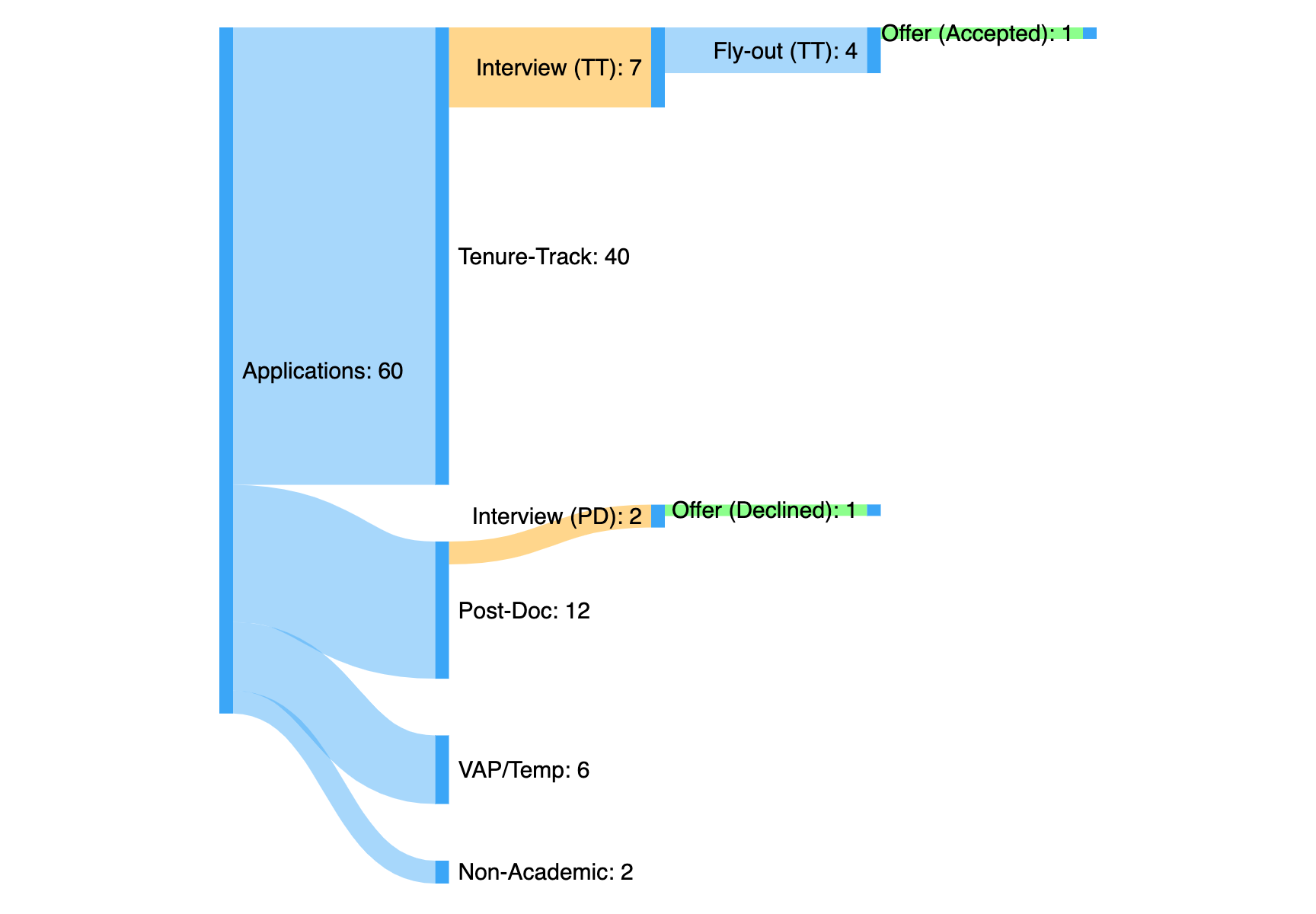

The post shares some details of Professor Davis’s job searches, with numbers and graphs:

Data from Davis’s last year on the job market.

But he cautions:

Please don’t take me as offering advice here. That’s not what I’m doing. I’m just sharing my information in an area that I find otherwise rife with opacity. This is intended only as offering perspective, not any type of roadmap for you…

I don’t think my journey on the market offers too many lessons that we didn’t already know; and when it looks like such a lesson might be available, I suspect it’s not very replicable—it’s too specific to my circumstances, the circumstances of the job itself/the committee/the university/the other candidates. The randomness of this process is just so pervasive.

And in a way, this is sort of the rub: while I know I worked so hard to get here, I don’t think I earned it in any real sense. I, like every other job candidate, made a series of choices, over the course of many years, that happened to align in the right way—in some sense better than a sufficient number of other candidates—with the needs and interests of a certain group of people who just so happened to be hiring that year.

You can read the whole account here.

I’d like to comment on this line from Jeremy’s excellent and informative post:

“There were a few instances where my nationality counted against me: certain jobs in Canada and the UK were out of reach for non-nationals.”

American candidates, alas, have good reason to believe that they won’t be considered seriously for Canadian jobs. Consider, for example, this boilerplate that my institution requires us to include in our job ads:

“Please note that all qualified candidates are encouraged to apply; however, applications from Canadians and permanent residents will be given priority, in accordance with Canadian immigration regulations. Candidates must therefore indicate in their application if they are a permanent resident or citizen of Canada.”

This statement, however, is misleading.

In fact, our search committees can indeed recommend US nationals for positions, and if such recommendations are approved, the institution is *not* required to provide the federal government with a Labour Market Impact Assessment, the purpose of which is to show that no qualified Canadian was available. This means that, in fact, no procedural barrier to hiring an American over a Canadian exists.

I believe that, prior to NAFTA (1994), the requirement to prioritize Canadians over non-Canadians was rather stringent. But NAFTA required that exceptions be possible for citizens of the US, Mexico, and Chile, and this persists in the various successor agreements. For this reason our current ad (AOS Metaphysics) includes the following, in bold:

“(Note: exceptions to this prioritization may apply for citizens of the United States and Mexico under the provisions of the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement, and for citizens of Chile under the provisions of the Canada-Chile Free Trade Agreement. Exceptions to this prioritization may also apply to candidates who are fluent in French.)”

I should add that I am not on my department’s search committee this year, though I have served on and chaired many search committees since joining TMU (previously Ryerson University) in 2006.

And I don’t doubt that some faculty in Canada and some department may have a preference for Canadian applicants. But that preference is not a regulation.

It’s also worth noting that US departments are legally required to preferentially treat Americans in the exact same way, although they needn’t advertise the fact like Canadian departments must. It seems to matter about the same as for Canadian institutions–i.e. it makes a difference at small institutions (especially those poorly equipped to deal with visa issues), and basically none at larger ones.

Thanks for clarifying, David. Two points.

First, there are definitely a number of Canadian postdocs (for example) that can only be held by Canadian citizens (such as SSHRC, Banting, etc.) just as there are equivalents in the US that can only be held by American citizens (NEH, the Society of Fellows at some universities). These kinds of jobs do really exist in both Canada and the US, speaking as a Canadian who has not been eligible for a number of American postdocs and VAPs due to the US citizenship requirement. The eligibility requirements for these jobs are strict and serious. Candidates who do not meet them will in many cases be ineligible to hold the position. What’s misleading is to try and draw a general principle from one practice for one set of jobs at one department at one university. As you point out, other Canadian departments might have different rules and practices. I want to be clear that whether citizenship requirements are legal or whether they should deter Americans from applying to Canadian jobs isn’t totally relevant in the face of what the author is doing in his extremely helpful post, which is speaking to the different potential factors that might have played into how the job market turned out for him. One of the jobs he held did in fact have a citizenship requirement. Reflecting on my own experiences, my Canadian citizenship did in fact play a big role in the kinds of academic employment opportunities I got. Had those requirements not been in place, the applicant pool might have looked different, and things likely would not have played out for me in the same way. Denying that citizenship is a factor on the grounds that there supposedly isn’t a strict legal requirement to hire a Canadian for one type of job in a small handful of larger research departments and that it’s all just an HR formality is an unhelpful generalization. That’s not the point of bringing up the nationality factor in this post.

Second, this conversation about citizenship on the job market is rehashed every job cycle. There is a broader cluster of issues here (again, not directly relevant to the post) pertaining both to the idea of prestige bias (and the tendency of Canadian departments to not hire PhDs from Canadian institutions) and to the fact that there are simply SIGNIFICANTLY fewer jobs in Canadian philosophy departments compared to total jobs in the US—in fact there are far, FAR fewer jobs in Canada than the total number of talented, accomplished Canadian PhDs on the market each year who have very good reasons for preferring jobs in Canada. This tends to be an extremely sore spot for displaced, homesick Canadian PhDs who are just trying to move back home to their families and communities. Without bringing the legality of such a requirement into play, these issues make it difficult to understand the impulse to defend these so-called loopholes so forcefully. I’m not making a normative point about the potential for such a policy, I’m just contextualizing the frustration by appealing to an existing debate. These are just some examples from over the years:

https://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/phd-to-what-end/

https://cha-shc.ca/precarity/is-it-time-to-restore-the-canadians-first-hiring-guidelines-for-canadian-universities

https://biopoliticalphilosophy.com/2022/05/28/prestige-bias-in-canadian-philosophy-hiring-practices-reprised/

https://www.universityaffairs.ca/opinion/in-my-opinion/the-value-of-where-you-earned-your-phd/?utm_source=University+Affairs+e-newsletter&utm_campaign=0f0dc537d1-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2018_11_21&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_314bc2ee29-0f0dc537d1-425250657&fbclid=IwAR1Ua5Ctict1gd9ntTFbj2or-DrQA6-Lt1EB11dNcCKUFotJan0h0LS9LgI

These are fair points, though I’d want to disentangle hiring Canadians vs. hiring people with Canadian PhDs. On the one hand, as someone at an R1 in Canada, we have many international (non-Canadian) students. They will – perhaps – suffer from “prestige bias” when trying to find jobs in that our program is not viewed as strongly as some programs in the US. (While our program has 9 Canadian faculty, only 3 of these received their PhDs from Canadian institutions. This advice won’t shock anyone, but it is probably best to go to the most prestigious program you can (with respect to general job placement) – regardless of whether in the Canada or US – to max your chance of a job.) Of course, the US has approximately 10 times the population and 10 times the number of jobs, (as well as producing 10 x the number of PhDs?), all of which affect the dynamics here.

All well taken, thank you!

I noticed the discussions in the links do in some places conflate Canadian citizens who hold PhDs and people who get their PhDs from Canadian institutions. Though like I said (and as you note), it’s a complicated dynamic and a complicated cluster of issues.

I want to add is that there are good reasons for these policies beyond what has been said. In the past century, university professors in Canada were more involved in public life, and contributed to building our institutions. That is much less true today, partly because of changes in the academy’s culture, but also the proliferation of American faculty.

American faculty are much less likely to get involved in politics or public life here. Some of that is not being familiar with the terrain, feeling like an outsider, or just using a Canadian school as a waystation to get back to the US. There are exceptions, who have my deep respect, but it’s generally the case. This also extends to the content of courses. At my institution there is a intro ethics course the focuses on current events. Since it is taught by an American, it focuses on US political events. If the events most relevant to the students in the class (e.g., Quebec nationalism, Indigenous issues, etc.) are mentioned, it’s in passing to compare them to distant American concerns.

For more, I recommend Stephen Clarkson’s essay: “Personal Success vs. Public Failure” in The Public Intellectual in Cnada. He was around to see this transition happen.

I stopped looking after 5 years. I didn’t even know people would even consider me for a job after the 5-year mark. My department did not say anything about that and neither did my advisors. Wish I had read this years ago in some other possible world, one in which I earned a living wage.

Congratulations on your achievement, Jeremy. You deserve it.

I’m also sorry, though, that you and so many other people have to go through so much just for (and yes, I said ‘just’) a job. I know, it’s your (and others’ dream) job; and for many it is more than a job. But it is, alas, still a job–you perform services; they pay you; etc.–and the Hunger-Games style weeding process to get this job is frankly disgusting.

One day I hope many newly minted PhDs will look at this rigmarole and say ‘No thanks: the university doesn’t deserve my sacrifices.’ And when that day comes I hope there will be a reckoning, so we can return to a much more humane process of finding employment.

It’s just a job, and not even a particularly attractive one if, like me, what you enjoy about philosophy is reading and writing it.

Having to deal with uninterested and mostly incompetent students and mounds of their slapped-together-the-night-before papers for the rest of my working career does not sound like a dream job to me.

Sure, maybe you’ll win the lottery and get that 2-1 teaching load with plenty of sabbaticals and helpful, pleasant colleagues and bright students. Or maybe you won’t.

Many grad students have the idea that philosophy is their one true calling and that they could never be happy doing anything else. But many grad students went straight from undergrad to masters to PhD and have no experience of anything else. I suspect there is a large overlap between these groups.

None of what I said applies to those who enjoy their teaching (weirdos).

I couldn’t agree more. I haven’t graded in years, and participation in some great reading groups has kept my reading active and interesting.

Data point: I was on the market for 10 years before I got a tenure-track position. Fortunately for me, those were all VAP positions, not adjunct, so when I did get a TT position, I was able to go up early for T&P. But the 10 year slog was not pleasant, a real test. Each of those 10 years I applied for about 100 positions. Got some APA interviews (this is back when we still did that), and a few fly-outs. My penultimate position was a 3-year non-renewable, so I told myself “at the end of this, it’ll have been 10 years; if I can’t get a TT position by then I should probably find some other line of work.” What’s this all show? One takeaway is the importance of perseverance and faith in oneself, but the other takeaway is the luck of being in the right place at the right time. There are a lot of jobs, but unfortunately way more people looking for those jobs. It’s rough, and sometimes it works out ok, but other times it doesn’t. I think we all need to realize that. I don’t tell students “don’t go, you’ll never get a job,” because look at my story – but I do tell them it may be a multi-year saga. OTOH, since I’ve been on the other end of the hiring table, we’ve hired several people who were just finishing up. So you never know. It’s not all talent, but it’s not all luck either.

I was also on the market 5 years before I got a TT job. I had good positions, but I was underpaid, and overworked. And I had to move three times, and uproot my partner. I love my current job, and I enjoyed my previous tenured job for many years. When you spend so much time getting a TT job you lose other opportunities. Now when I talk to early career people who are looking for TT jobs I get really unsettled – I relive the past. Perhaps what kept me going in part was the fact that I met accomplished philosophers who had TT jobs, and told me their stories of being on the market 5 to 7 years.