Intergroup Dialogue in the Philosophy Classroom (guest post)

“Over 70% of our students… reported being more likely than before to listen to someone who held an opposing viewpoint…”

The following is a guest post* by Wes Siscoe (University of Cologne, University of Graz) and Zachary T. Odermatt (Florida State University. It is part of the series of weekly guest posts by different authors at Daily Nous this summer.

Intergroup Dialogue in the Philosophy Classroom: Helping Students to Have Productive Conversations about Race and Gender

by Wes Siscoe and Zachary T. Odermatt

If you’re reading this blog, we don’t need to tell you that there are a number of challenges to allowing undergraduates to have a class-wide, free-for-all conversation about the philosophy of race or the philosophy of gender. Nevertheless, ongoing dialogue is an important part of doing philosophy, making it a priority to teach students how to discuss even the most challenging of topics. In order to help students build the necessary skills to have constructive conversations about race and gender, we used an Innovation in Teaching Grant from the AAPT to create a course centered around weekly dialogue groups. In this post, we will describe the structure and format of our dialogue groups, explain how they were able to overcome some obvious challenges, and provide you with the resources to create dialogue groups in your classes.

Students have a number of fears when discussing controversial issues like race and gender. Many of our students were concerned that they would accidentally say something racist or sexist, while others worried that they would be the targets of racism or sexism. One promising method for confronting these fears is intergroup dialogue—sustained, small group discussions with participants from a variety of social identities. In 2008, a group of nine universities set out to explore whether intergroup dialogue could help students have conversations about race and gender, a project known as the Multi-University Intergroup Dialogue Research Project. What they found was that intergroup dialogues helped students improve their communication skills and grow in empathy and understanding, helping them to overcome their fears of being seen as racist or sexist or being the targets of racism or sexism.

In order to incorporate the lessons learned from the Intergroup Dialogue Project, we designed dialogue groups that emphasized student leadership and a strong sense of community. To begin with, we gave students ownership over their dialogue groups. The groups, each of which had 20 students, met once a week for the duration of the semester and were supervised by TAs. The first day of dialogue was dedicated to students creating their own group norms, the ground rules that would guide their discussions throughout the semester. Potential norms included the following:

- Charitable Listening – Always assume that group members mean well when they share, and allow them to clarify if they feel that have been misunderstood

- No Generalizing – No reasoning about others using generalizations, either positive or negative

- Names Stay, Ideas Leave – Continue discussing interesting ideas outside of the classroom, but do so without attaching participants’ names to stories or beliefs

After the first day of dialogue groups, during which students chose their group norms, the dialogue sessions were facilitated—not by faculty or TAs—but by the students themselves. Students were assigned a partner along with a day that they would lead the discussion, creating a decentralized power structure that gave the students the primary role in creating a productive conversation.

In order to further build a sense of community, each session began with an ice-breaker activity to help students get to know one another on a more personal level. These activities were designed both to encourage familiarity and camaraderie as well as prompt thoughts and ideas that would be relevant to the subsequent discussion. To allow the sense of community time to develop, discussion topics at the beginning of the semester should be kept fairly non-confrontational. For instance, a helpful early semester discussion-starter might be, “What is a positive aspect of what you see as masculinity?” as opposed to, “What makes someone a man or a woman?” Discussion topics like these allow students to practice following the group norms without diving into the most difficult issues right at the outset.

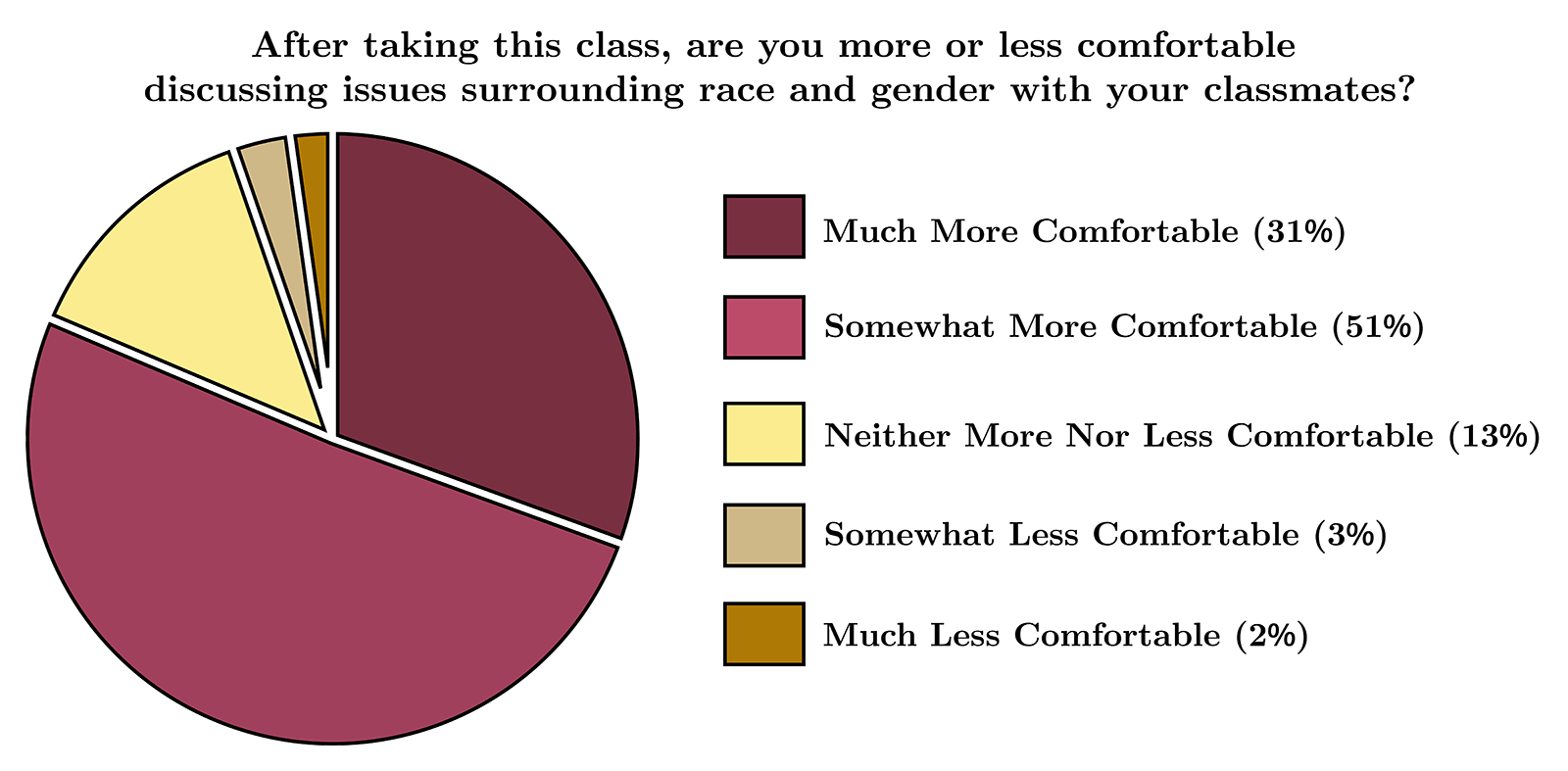

Here are some of the most promising results from our course. In the post-course survey, over 80% of students agreed that they were more comfortable discussing issues surrounding race and gender than they were before, with only 5% saying they were less comfortable, while over 70% said that they are now more likely to initiate similar conversations outside of class. Over 70% of our students also reported being more likely than before to listen to someone who held an opposing viewpoint regarding issues of race or gender, while only 4% said that they were less likely to do so. Here is the full breakdown of how the groups affected the comfort levels of dialogue participants:

If you’re interested in adding dialogue groups to a class covering the philosophy of race or the philosophy of gender, then here is everything you need to get started. Feel free to download all of the rubrics and documentation, modifying them as necessary!

- Scheduling your Dialogue Groups – How you schedule your dialogue groups will depend on how many students you have. If your class has less than 25 students, then you can simply make one class session a week into a dialogue session that includes all of the students. If you have more than 25 students, then you should consider creating multiple dialogue groups. In our case, we had 120 students, so we created 6 dialogue groups that met once a week, with each TA leading 1-2 dialogue groups. If you do not have TAs, you can still create multiple groups by staggering when and how often they meet. If you have 40 students, for example, you can have a 20-student group meet each week, rotating which group meets, or you can schedule both groups each week, having them meet back-to-back.

- Creating Group Norms – The initial dialogue session was led by the course instructor or TA, explaining the structure and goals of the dialogue group. As a part of this session, the instructor or TA also led the students through the process of choosing their own discussion norms. Students might not be immediately familiar with what qualifies as a helpful group norm, so sharing a number of examples is often a good way to get started. See this link for more guidance on creating group norms, along with a full list of example norms.

- Assigning the Lesson Plan – At the initial dialogue session, students were randomly assigned a partner and a day that they would lead the discussion. Several days before their assigned discussion group, they turned in a lesson plan that included dialogue activities and discussion questions (here is an example of the lesson plan that one pair of students created). In order to help them create effective lesson plans, students were provided with this rubric, this list of possible dialogue activities, and feedback on their lesson plans, making revisions to their initial lesson plan before they ultimately led the group discussion.

- Grading the “Presentation” – Students also received a grade for how well they led their dialogue group. Along with earning points for revising and executing their lesson plan, they earned points by creating a sense of community on their discussion day—arriving early to greet everyone, encouraging everyone to participate in the conversation, and asking effective follow-up questions. The rubric that we used to grade dialogue leaders is here.

Maybe you’re not convinced yet that dialogue groups are the way to go, so before we close, we’d like to address a couple of concerns. First of all, having weekly dialogue groups takes away from instructional time, raising the possibility that such groups will prevent students from mastering the course content. Not a lot of research has been dedicated to this issue, but what has been done suggests that dialogue groups might add to, not detract from, student learning outcomes. When compared to large lecture courses, for example, intergroup dialogues did not detract from student mastery in a course on the sociology of race and ethnicity. This could be because dialogue groups are a form of active learning, giving students a chance to use concepts that they have been learning in the classroom.

Secondly, by adopting the dialogue format, the instructor relinquishes a fair amount of control over what students say, raising the concern that dialogue groups open the door to hurtful and demeaning comments. This is an important concern, and demonstrates why it is essential to have an instructor or TAs oversee the discussions. While they are not there to lead the group, the TA or the instructor has the final say on what does and does not qualify as constructive conversation, playing an important role in helping students feel comfortable enough to share their own thoughts and experiences. For a full description of our dialogue groups, along with the pedagogical considerations that went into designing them, see our forthcoming paper in Teaching Philosophy, or feel free to ask away in the comments!

[top image: detail of string art by Ani Abakumova]

The restriction on generalizations seems problematical to me. If generalizations or stereotypes are a problem, don’t they need to be surfaced and dealt with?

Ron –

That’s a great point! Unhealthy stereotypes and generalizations do need to be dealt with, but there is also a difficult question about the best way to do that. For the majority of our students, the experience of having others talk about them during class using generalizations did not help them feel comfortable participating in the dialogue, so they chose to have a norm against those sorts of comments. Students were still allowed to raise what they saw as unhealthy stereotypes, so those were still able to be addressed, but the norm was against using these stereotypes to then reason about others in the group. Hope this helps!

This program sounds awesome! I’m very impressed.

There does seem to be a problem regarding banning generalizations or having an official position that they are a problem. Many students political views seem to be based on generalizations, but this takes those views off the table. Maybe it’s ok to ban views that can be shown to be empirically false. I’m not sure.

Also, what about generalization like “all people of group X are privileged/disadvantaged by being members of group X”? What about a generalization like “a straight person can’t truly understand what it’s like to be gay” or “all white people are racist”? Can these not even be discussed?

Beyond that, how about generalizations like “Students who do their readings carefully will be better prepared for class discussions?”

“People of color/women are oppressed” is a generalization, isn’t it? It would be hard to have a good Feminist Philosophy or Philosophy of Race course without discussing those. I suppose the role of the instructor would be to point this out and help guide productive discussion about what that implies about discussion guidelines. This could led to a better targeted guideline.

Thanks for all of the great questions!

For students that wanted a norm like “No Generalizing”, their stated goal was often that they wanted to be treated as individuals, not as the group’s “representative” of their particular social identity. And they also didn’t want members of the group to speak of them that way, which we thought was a helpful suggestion.

As many have pointed out, there might also be downsides to not being able to talk about dialogue group members using generalizations, and if that’s something that you would like to include in your dialogue groups, there might be other, nearby norms that can help students accomplish similar goals but avoid the mentioned drawbacks. So what I would recommend is, if students want a norm like “No Generalizations”, to help them think through possible downsides before they ultimately settle on their final list of norms. Thanks for all the great feedback!

Just to be clear, Wes: I think this is a great project, and I think the other two norms you presented are excellent and ought to be followed more widely.

I’m still finding the ‘No generalizing’ one tricky, though. As you put it, it says “No reasoning about others using generalizations, either positive or negative.”

I think the problem is the other way around: what causes problems is not reasoning about others using generalizations, but rather applying generalizations in an unreasoning manner, or applying generalizations that have not been reasoned about fairly or are not allowed to be reasoned about fairly.

Jason suggests that the generalization “People of color/women are oppressed” must be discussed in any decent Feminist Philosophy or Philosophy of Race course. That may be true, but the key word here is ‘discussed’. If the professor, the students, or the authors of the readings were permitted to assert that such generalizations are true or false without having those claims subjected to sustained and well-informed criticism, then the course would seem to engage in indoctrination rather than the teaching of philosophy.

Maybe a good norm would be to encourage people to present counterexamples to any such claims, and also to encourage people making general claims to specify how broadly it is meant to apply. There’s a difference between saying ‘All As are Bs’ and ‘As tend to be Bs’, but careless thinkers often say ‘As are Bs’, which generally implies the former.

This main issue seems to come up quite often in statements like ‘As need to listen to Bs about C’ (which implies the generalization that As cannot learn the truth about C without the help of Bs, that Bs agree about C, and that what the Bs think about C is clearly correct), or statements like ‘As an A, you mistakenly think that P; but as a B, I understand that Q’ (which assumes the generalization that one can read P-belief from the fact that the other person is an A, and so on). Once these sorts of statements become permitted without challenge, discussions go off the rails of philosophy and into something else. But I think the main problem here is not that people make the claims, but that the claims go unchallenged by any reasoning or counterexamples. So perhaps just a general norm in favor of critically examining generalizations and stereotypes is the best thing for addressing bad modes of reasoning that are, unfortunately, encouraged in other courses our students take.