“Departments of Cognitive Poker”? Competitiveness and Philosophy (guest post)

Is philosophy an especially competitive discipline? How? Is its competitiveness a problem? If so, what might we do about it? In the following guest post*, Christina Easton, British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Warwick, takes up these and related questions.

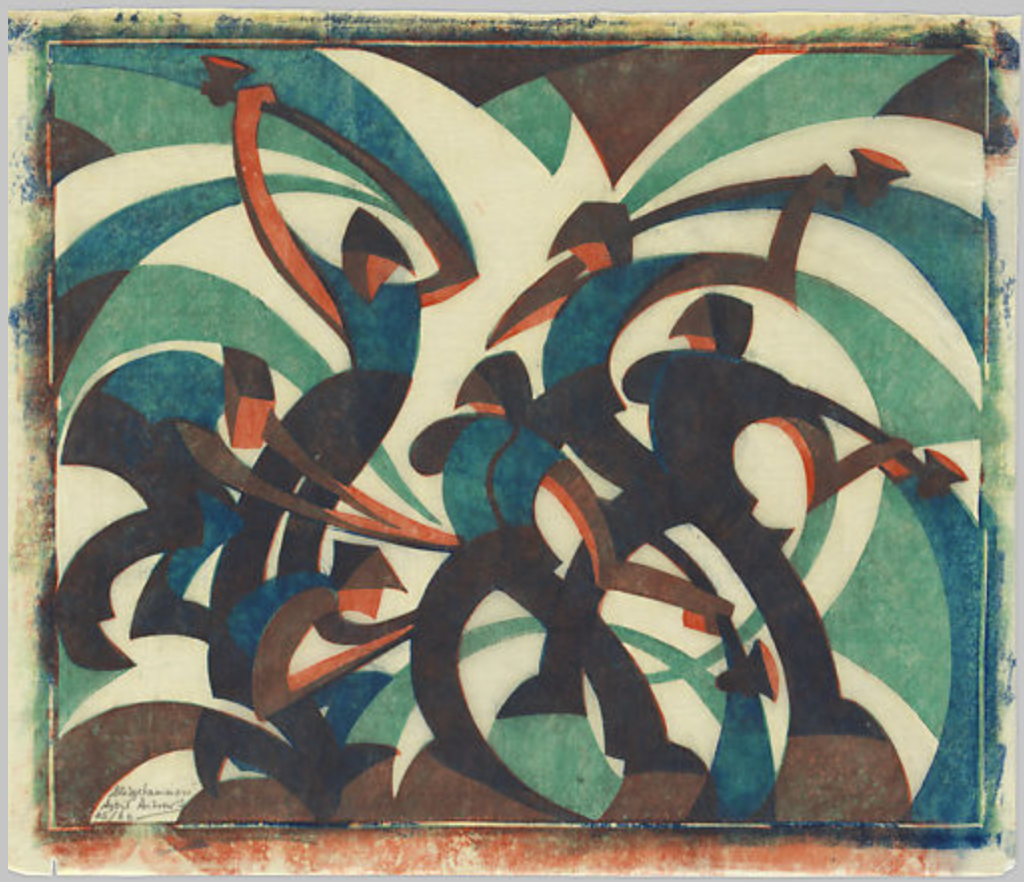

[Sybil Andrews, “Sledgehammers”]

“Departments of Cognitive Poker”? Competitiveness and Philosophy

by Christina Easton

In his memoir The Making of a Philosopher (2003), Colin McGinn describes his experiences of philosophical debate as involving

a clashing of analytically honed intellects, with pulsing egos attached to them … Philosophical discussion can be a kind of intellectual blood-sport, in which egos get bruised and buckled, even impaled… Plain showing-off is also a feature of philosophical life.

Commenting on this in her own memoir The Owl of Minerva (2007), Mary Midgley criticises this “competitive conception of philosophy”, joking that (since, in her view, it might be detrimental to the core enterprise of philosophy) these activities might be practised apart from philosophy, in “Departments of Cognitive Poker, or Institutes of One-Upmanship”.

To what extent is this “competitive conception of philosophy” still dominant today? And what place ought competition to occupy in philosophy? (These questions are tackled in a new, open access Special Issue on the topic in the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.)

There is one obvious sense in which philosophy is highly competitive, and that’s in the sense in which academia, in general, is highly competitive: we compete against each other for scholarships, jobs, funding, etc. It may be that philosophy stands out as more competitive than other disciplines here, due to factors such as lesser availability of funding and more people looking exclusively for academic jobs following a PhD. But what about the practice of doing academic philosophy? Do the norms and practices of philosophy stand out from other disciplines as being especially competitive?

One increasingly well-discussed way in which philosophy might stand out as being competitive is with its focus on combative dialogue. This is highlighted by the language of competition and fighting that we use to describe what goes on at, for example, Q&As following research talks. We “attack, target and demolish an opponent” (Haslanger). Arguments suffer from “fatal flaws” and get “shot down” by counter-arguments (Rooney).

When combative dialogue in philosophy gets highlighted as problematic, note that it’s not usually the adversarial method itself that is ‘under attack’. Given the distinct subject matter of philosophy as addressing particularly intractable questions that are often unresolved by empirical evidence, presenting arguments and having people identify ways that such arguments go wrong is part and parcel of what it is to do philosophy. Rather, the issue is more with the manner in which this feedback on arguments is given. Counter-arguments are often presented in a nit-picking, competitive manner, so as to give the impression that the speaker is stupid and the interlocuter superior. Post-presentation Q&A can involve relentless attacks on the case just presented by the speaker, with the primary goal of audience members being to find flaws—any flaws, however minor—in what was just said, in order to prove that the speaker is wrong. These “competitive attacks are unending” (Friedman); the back and forth of argument is expected to continue until one member ‘surrenders’, at which point, someone has ‘won’ and someone has ‘lost’.

If there is a competitive atmosphere in philosophy, why might it be problematic?

First, there is Midgley’s worry that competitive behaviours might get in the way of what philosophy is really about. If we think that philosophy is a search for wisdom or the pursuit of truth, then we might worry that research seminars dominated by verbal smackdowns between competing individuals gets in the way of this. Competition encourages epistemically vicious modes of conduct; for example, grandstanding and one-upmanship can draw focus away from the search for truth and onto the individuals making arguments.

Second, and as I argue in a recently published open access article, competitive norms might be bad for philosophy by contributing to a lack of gender diversity within the discipline. One major reason is because competitive norms may lead to women performing less well in philosophy than they might otherwise do. Research indicates that performing a task as part of a competition tends to make men perform better than they would have done had the task been non-competitive, whereas it tends to make women perform worse. Women also tend to have more negative attitudes towards competition—partly mediated by their tendency towards lower confidence (something which I think is, independently, an explanatory factor in the gender gap in philosophy). If women tend to enjoy competition less, then this might (for some women) lead to them viewing research talk Q&As as ordeals to be endured rather than as an enjoyable game or contest.

Yet even if the research is wrong and in fact these gender differences do not exist, stereotypes that say that women are non-competitive can have pernicious effects. First, they may lead to ‘backlash effects’ against women who exhibit counter-stereotypical traits. Women who enjoy and show skill at “intellectual blood-sport”—and maybe even engage in some “showing-off”—may be the subject of hostility, resulting in fewer opportunities and less enjoyment of participation in philosophy. Second, competitive norms in philosophy combined with gender stereotypes relating to competitiveness may result in people developing conflicting schemas (sets of implicit and often unarticulated expectations) for ‘philosopher’ and ‘women’. This may contribute to women feeling that they do not belong in the discipline and consequently choosing not to continue (or begin) philosophy.

If this is right and there are major downsides to a competitive atmosphere in philosophy, what might we do to make competition a less dominant feature of the practice of academic philosophy?

One thing we might do is to improve the manner in which we engage in dialogue with each other, for example by working to eliminate norms where it’s acceptable to relentlessly attack a presenter or to nit-pick for the sake of proving someone wrong. (This might be especially helpful for the gender diversity issue just discussed, since research indicates that the gender gap is largest in competitions that reward stereotypically male traits such as aggression.) In this area, philosophy has already improved: people are less rude, and dominating a discussion tends to be frowned upon. As Helen Beebee writes in her recent assessment of what’s changed in philosophy in the last decade, “People are just nicer to each other”.

But note that being nicer to each other doesn’t fully resolve the problems flagged with competition above. Even where comments are delivered in a polite manner, alongside smiles and compliments about the paper, the competitive element remains. To borrow some words from Joseph Trullinger, it just makes it more of a gentlemanly duel as opposed to an unsportsmanlike war. The notion that one stands up in front of an audience and defends one’s view in an attempt for it to ‘win out’ amid the criticisms of the crowd is still very much alive.

Is that competitive, ‘duelling’ element just inherent to philosophy? After all, examining arguments is key to philosophy (at least, in its dominant practice in today’s academy), and arguments can be won or lost. Perhaps then it is the “pulsing egos” attached to the arguments that are the problem. It’s our tendency to own an opinion or argument, to see them as things to be defended at all costs on pain of one’s honour, that is problematic. If instead, we re-focused on our shared mission of uncovering truth or wisdom, then that competitive element might lessen—we’d delight in being proved wrong.

One practical means towards this change might be to use more group-orientated language when engaging in dialogue. For example: “Perhaps it might help us work this out if we attended to…” Or: “In light of X, we might need to revise our thinking on Y…”

We might also endeavour to place less emphasis on the need to ‘pick a side’. When we ask undergraduates to state their thesis as they introduce their paper, we could emphasise that this thesis need not be that a particular side of the debate has won out. Instead, it could identify which argument is the biggest threat to a theory, for example. When we review for journals, we could be more open to papers that don’t defend a particular point of view, but instead shed new light on an issue and acknowledge its complexity, before raising some questions that arise from the reflections.

On this last point we can take a lesson from Elizabeth Anscombe, about whom Bernard Williams recalled:

she impressed upon one that being clever wasn’t enough. Oxford philosophy, and this is still true to a certain extent, had a great tendency to be clever. …there was a lot of competitive dialectical exchange, and showing that other people were wrong. I was quite good at all that. But Elisabeth conveyed a strong sense of the seriousness of the subject, and how the subject was difficult in ways that simply being clever wasn’t going to get round.

Perhaps if, like Anscombe, we were to take philosophy a bit more seriously, as a genuine attempt to try and better our understanding, then we wouldn’t be so inclined to slip into “rough play”, for philosophy wouldn’t be a game at all. If it’s about trying to dig deeper into important but difficult questions, then there’s no need to ‘own’ an opinion and stick by it. Instead, we should happily relinquish a view when we find that the weight of argument takes us elsewhere, and we should not feel ashamed at that. If more of us could have that attitude—something that unfortunately modern academic practices pushes against—that would reduce the emphasis on individual competition and individual accomplishment.

I would be very interested to hear in the comments what people think. Does philosophy stand out in academia as having a competitive atmosphere? If yes, is this a problem? I’ve focused here on competition’s downsides, but are there upsides to competition and competitive atmospheres that might mean that overall, it’s a good thing? If it is problematic, what might we do to improve things?

When a piece of philosophical writing is ambiguous, open-ended, or allusive, it’s fun to find new interpretations, and that can make you feel smart. But when philosophical writing is very clear, unambiguous, and explicit, it tries to do all your thinking for you, treating you as passive. “Just give your assent,” it seems to say. And then there’s an easy way to feel smart: go on the attack, try to pick apart the argument. That’s one reason, I think, why analytic philosophy is combative. It has to do with the kind of communication we like.

I generally prefer to read academic material where the author’s goal is to explain something to me as clearly as possible, rather than to make me feel smart.

There is considerable scholarship on this within Argumentation Theory. For one of the latest special issues on the problem of adversariality in argumentation, see here: https://link.springer.com/journal/11245/volumes-and-issues/40-5

This is hella cool! Thanks much for the link.

When the goal is wisdom and truth and the quality of that information in any conversation being of first importance, then one does feel happy to be wrong cuz they gained more in the exchange.then if we desire to put that to good use to help others from the good of love then wisdom has served its purpose. This is very well put.

It often feels to me like we’re overly-trained in how to come up with counterexamples to propositions. Which kinda makes sense: if someone asserts P, then we’re off to the races wondering whether ~P and, if so, why (or how to instantiate). I guess in some generic sense, this is what all disciplines do, e.g., scientists checking replicability of some experiment. But somehow in philosophy, it feels more “personal” because we aren’t just talking about what the quarks or spike proteins are doing, we’re talking about some generally non-empirical hypothesis that’s mostly (or only) supported by intuitions in which we’re personally invested.

This isn’t terribly constructive, and there are ways in which it bleeds out of the profession into other stuff we do. E.g., wife asks whether we should have spaghetti for dinner, and you’re quickly surveying all of the available epistemic spaces to see whether that’s *really* what we should be having. Is there something else in the refrigerator that’s more time-sensitive? What’d we have yesterday? It’s another instance where something sort of like “falsification” is really at play.

It’s really tedious. It feels like philosophy could, in some sense, be more “constructive”, or at least “collaborative”. We’re too interested in logging “objections” to stuff, rather than building edifices that more or less tell us something informative. Philosophy talks are often awful for just this reason: everyone just wants to show off how smart they are by finding something to object to, rather than building a conversation. (At least at most of the places I’ve been to talks at.)

Thank you for the post!

Yeah, it’s one thing to be skeptical (which I take to be a large part of this job), but it’s another to be an argumentative bastard. Not always easy to tell which one you are, though…

On collaborative work, I really like Oliva Bailey’s “But How Do I Participate?” classroom handout:

https://obailey.weebly.com/uploads/1/0/5/6/105611057/bailey-but-how-do-i-participate-2021-edition.pdf

Thanks for the shout-out! I’m always looking to improve and expand the doc, so if anyone has elements to add to it, they should feel free to email me.

A minor suggestion: if you have an objection to something in a talk, you’ve made it, the speaker has responded, and perhaps you’ve followed up, and they’ve responded to the follow-up, let it go, even if they’re clearly wrong. It’s disrespectful of others’ time not to do so, but more importantly, almost no-one changes their mind in real time about some substantial thesis they hold. Your goal in stating the objection (once you’ve given the speaker an initial chance to explain why it is misconceived) isn’t to browbeat the speaker into recanting on the spot; it’s to communicate to the audience that there is a serious issue here, and maybe to give the speaker something to reflect on later.

Yes, yes, a thousand times yes. Speakers can also exercise some influence over this. “That’s a strong/interesting/complicated point. I am not sure how to respond. I’d like to think about this some more and follow up with you later.” Oh how I appreciate both speakers and objectors exercising self-restraint by refusing to initiate or get dragged into slapfights.

Shouldn’t this be the chair’s responsibility, e.g. limit all questioners to a maximum of one follow-up?

You could run a discussion that way, and often it’s a good idea to. But I’ve often been in talks where the discussion culture allows more extended exchanges. Done right it can be quite helpful, but it’s open to abuse.

When I stepped out of my little bubble at Irvine and got acquainted with the real world, I was really disoriented to find seminar meetings and colloquium talks conducted on a model other than “a group of people trying to help one another understand something” and it amazes me still that these other models have any attraction to anyone.

Agree – anything else, even if it advances knowledge, does not advance wisdom.

Another suggestion: forgo burden-shifting maneuvers. In philosophical discussion, they are (I think) rarely called for, since it is rarely the case that one position clearly merits the status of “default”.

Would you mind elaborating? I didn’t quite understand this!

Sure, I can try to. Suppose we’re arguing, and I claim that the “burden of proof” is on you to show that such-and-such. What are the truth-conditions for my claim? I’m not completely sure, but here’s a proposal to start with: My claim is true just in case there are some positions on the topic we are discussing such that any reasonable standard for assessing credibility yields a strong presumption in favor of thinking that at least one of those positions is true, *and* something you have asserted contradicts all of them, *and* the resulting strong presumption in favor of thinking that what you’ve said is false won’t be defeated unless you show such-and-such. I strongly suspect this proposal can be improved upon! But I hope it’s on the right track. Assuming so, the reason that I think that burden-shifting maneuvers are rarely called for in philosophical discussion is that it is typically the case that the “strong presumption” condition isn’t met. It has *also* seemed to me (though this is based just on amateur sociological observation) that when philosophers use burden-shifting maneuvers in arguments with each other, they typically don’t *think* that the strong presumption condition is met, but instead are just trying to make an argumentative move that will put their opponent on the defensive, thereby increasing their chances of “winning” the argument. At least, I’m quite sure that that is exactly why *I* have used them! (Not proud of that face, needless to say.)

*fact

One might say the burden of proof is on anyone who makes a burden of proof argument

I think it is PvI who likes to say, “The burden of proof is on the person trying to prove something.”

Dallas Willard (USC) used to say, “I am always willing to accept the burden of proof because I’m the one who wants to know.” It stuck with me.

Bryan Frances puts it memorably: “Burden of proof arguments are for losers.”

(Quoting from memory from over 10 years ago, so I hope I got it right. But I remember it made me laugh out loud—a rare thing when reading philosophy.)

Great article and supportive research! You seem to be settling into this topic nicely. It’s great to see so many dimensions of competitiveness addressed so well.

Two researchers you quoted said the problem with competitiveness was related to “overconfidence” after stating that men tended to be more confident than women. To aim at more precision a bit: there is an ontological distinction to be made between Anscombe’s confidence and the overconfidence of a clever grad student- the similarity of the appellation is deceptive. One is productive and imo by definition careful, the other prone to be driven by unhealthy subconscious impetus, and by definition careless. Confidence easily allows restraint and an easy partial support during disagreement, the other doesn’t.

Which leads to my main, quite fuzzy point. A culture based, however politely, on argumentation, and that’s infected with overconfidence, will ask and answer fundamentally different, lesser questions than one based on inquiry and possibility. Obsessiveness about truth, which is typically obsessiveness about belief, and which lends itself ideally to the psychological excesses of argumentation, supplants more useful aetiology and teleology, discourages the natural search for practicality and contingency in a non-Boolean, non-essentialist existence, and attenuates way too early what gets on the spreadsheet as the good aspects of a given thought.

I have often said that, on average, women do better philosophy, about more interesting subjects, than men. I think it’s because of both the confidence and asking-different-questions points above. I would encourage anyone to read how Ruth Millikan, or listen to how Miranda Fricker, for instance, make and address points publicly; one can acquire a better sense in just a few minutes what it means to inquire, how much would be lost through a misplaced competitiveness.