New Data on Women in Philosophy Journals

How much writing by women do philosophy journals publish? How does this vary by quality and type of journal? How does it vary by the type of reviewing manuscripts undergo? How have women’s rates of publication changed over time?

These are among the questions answered by a new study of women’s publication in philosophy journals, just published in Ethics. The study, by Nicole Hassoun (Binghamton), Sherri Conklin (AviAI Inc.), Michael Nekrasov (Santa Barbara), and Jevin West (Washington).

In conducting their study, the researchers divided up philosophy journals into three categories: “top” (based on an informal survey at Leiter Reports), “non-top”, and “interdisciplinary” philosophy journals. They find:

- “an overall increase in the proportions of women authorships in philosophy journals between 1900 and 2009”

- “stagnant growth in the proportions of women authorships for recent decades, especially in Nontop Philosophy journals”

- “the proportion of women authorships has been lowest in Top Philosophy journals over time but that these journals show the greatest increase in the proportion of women authorships between the 1990s and the 2000s”

- “women authors are underrepresented in Top Philosophy journals even compared to the low proportion of women philosophy faculty in the United States overall”

- “the proportions of women authorships in lower-ranked philosophy journals and women philosophy faculty in the United States do not differ”

- “previously reported disparities in Value Theory [between the comparatively low proportion of women authorships and compartatively high proportion of women faculty] are sustained across all philosophy journal categories, including lower-ranked journals where women authors publish in greater proportions”

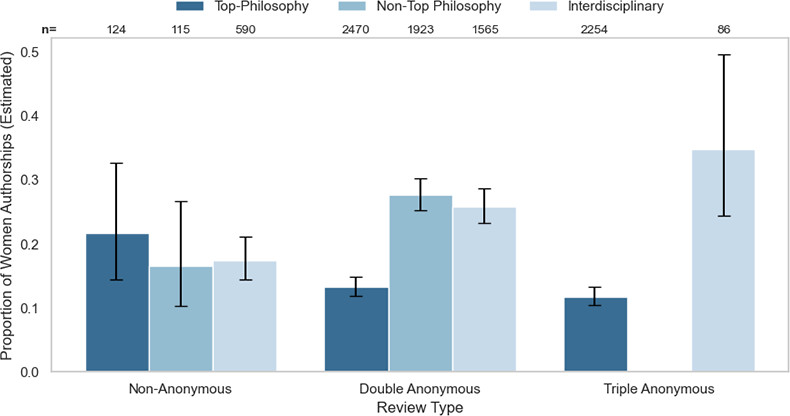

- “Top Philosophy journals practicing Nonanonymous review publish higher proportions of women authors… than Top Philosophy journals practicing Double or Triple Anonymous review… Nontop philosophy journals publish the greatest proportion of women authorships when practicing Double Anonymous review, the most stringent anonymization level within this journal tier… while Interdisciplinary journals publish the greatest proportion of women authorships when practicing Triple Anonymous review”

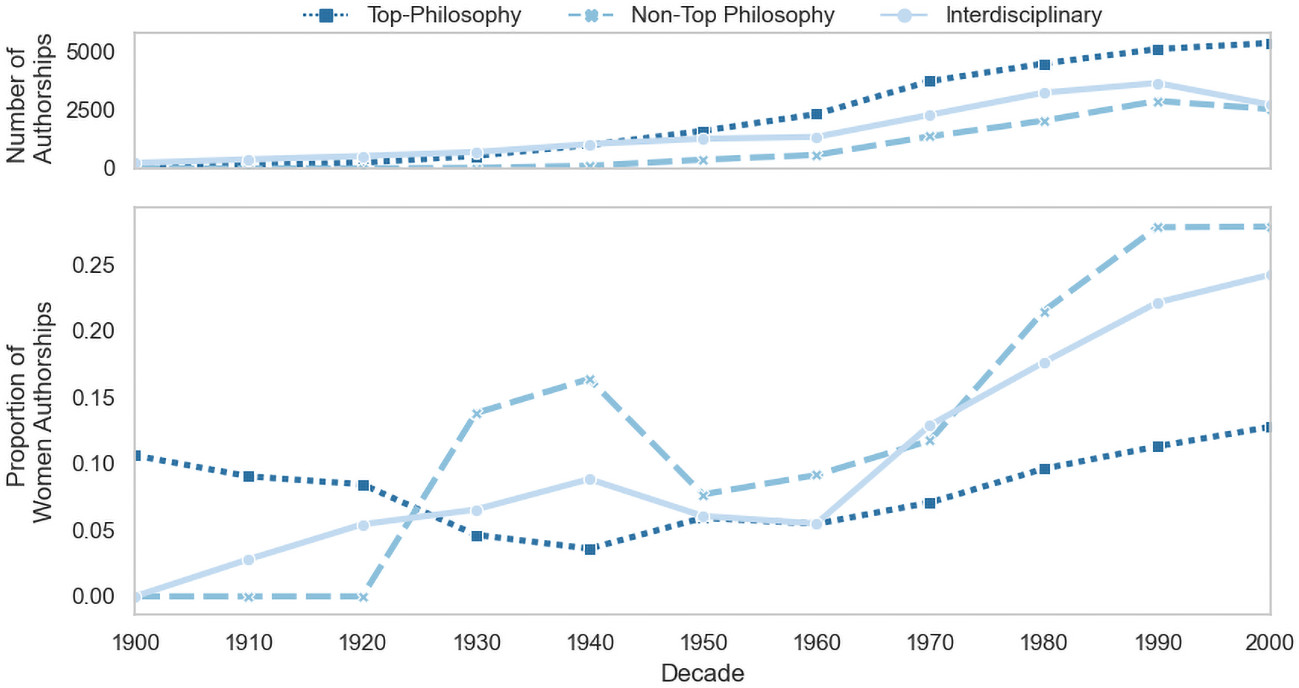

Below you can see the change in number and proportion of women authors in each type of journal from the 1900s to the 2000s:

(Fig. 4 from Hassoun et al.) Total proportion of women authorships by decade and journal category (1900s–2000s). The top graph shows the total number of authorships by decade and journal category; the bottom graph shows the proportion of women authorships by decade and journal category.

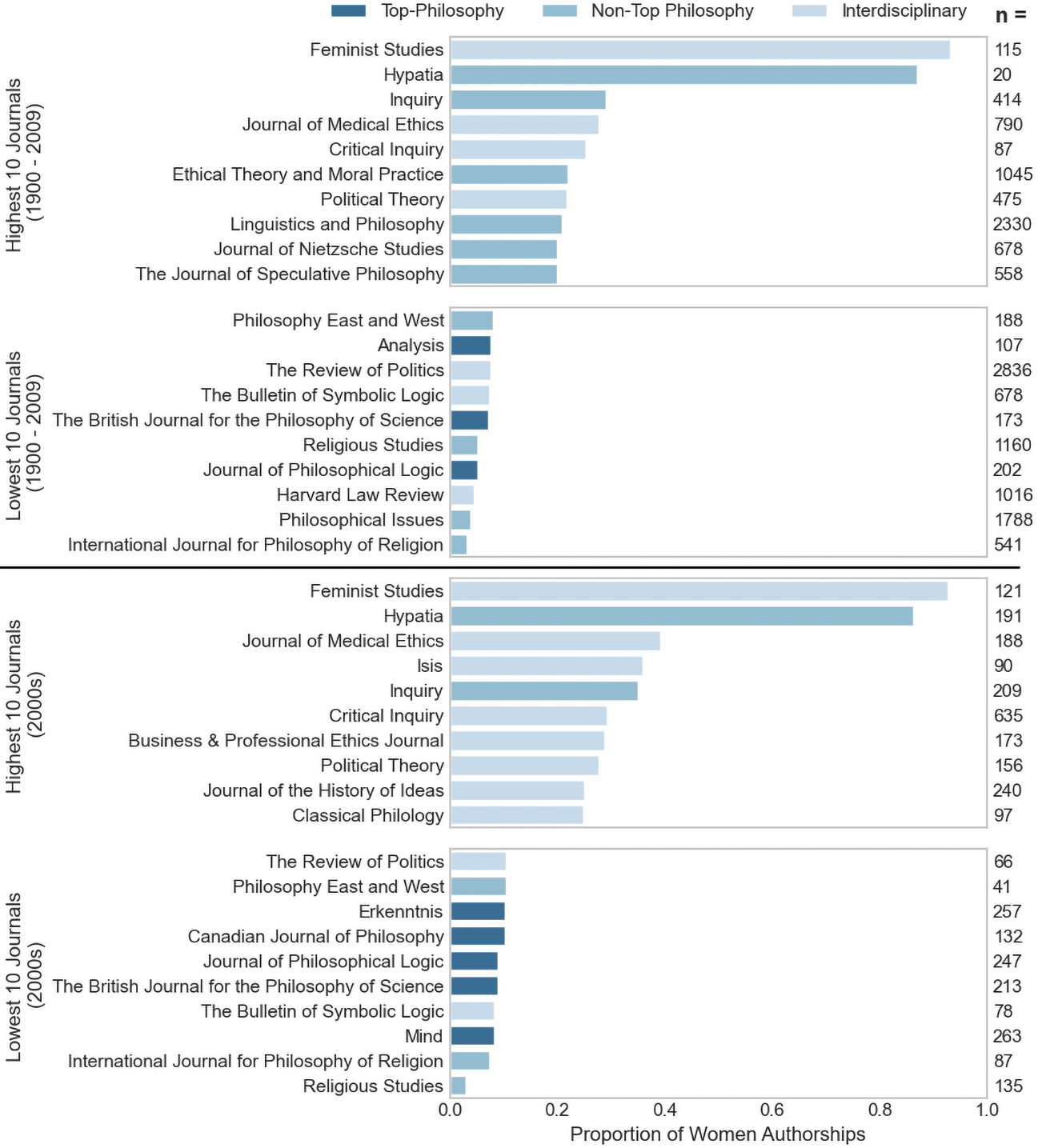

In the following figure, you can see which 10 journals have the highest proportion of articles by women and which have the least, for the periods of 1900-2009 and 2000-2009, color-coded by category:

(Fig. 2 from Hassoun et al.) Journals with the ten lowest and those with the ten highest proportion of women authorships for all three journal categories ranked by proportion of women authorships. The top two graphs represent the total proportion of women authorships across all years (1900–2009), and the bottom two graphs represent the proportion of authorships from 2000 to 2009. The total number of authorships per journal “n =” is shown on the right of the graph.

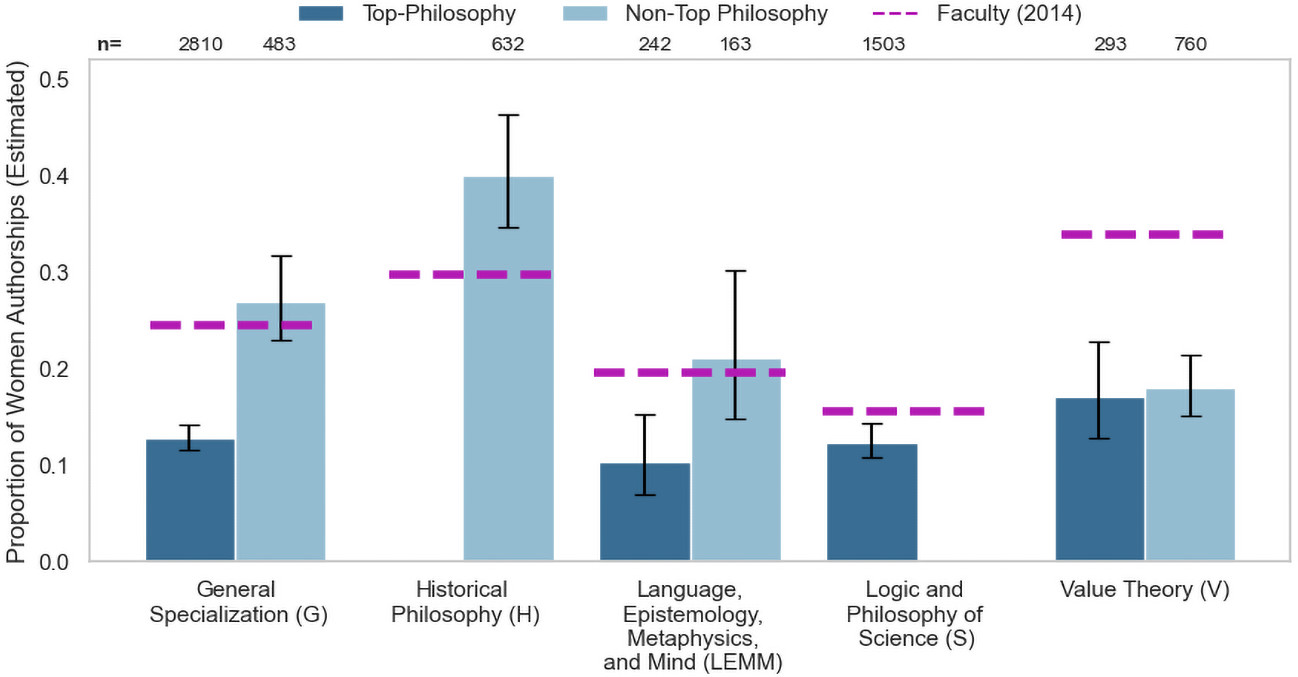

The authors also used a generalized linear model (GLM) to provide estimates of how women’s authorship in philosophy journals varies by area of specialization, and how this compares to the proportion of women working in these areas:

(Fig. 9 from Hassoun et al). Generalized linear model (GLM) estimates of the proportion of women authorships (2000–2009) by journal AOS compared to faculty AOS (2014). The mean estimated proportion of women authorships across all journals separated by journal category and AOS for the years 2000–2009. Error bars represent the CI based on the output of the GLM. The number of observations (articles for each journal AOS and category in the 2000s) is displayed at the top of the graph with the “n =” label. Note that this figure displays the mean proportion estimated by the model on all articles in a journal category.

They also used the GLM to provide estimates of how the proportion of women authorships varies by type of manuscript review (non-anonymous, double-anonymous, triple-anonymous):

(Fig. 11 from Hassoun et al) GLM estimates of the total proportion of women authorships across all journals separated by journal category and review process for the years 2000–2009. Error bars represent the CI based on the output of the GLM (the CIs are very wide owing to the limited data for Nonanonymous review). The number of observations (articles for each journal category and review type in the 2000s) is displayed at the top of the graph with the “n =” label. Again, note that this is the mean proportion estimated by the model on all articles in a journal category.

The authors discuss their findings and possible explanations for them. For example, regarding the finding that “top” philosophy journals that use triple anonymous review publish a lower proportion of women authors than journals that employ other review types, they say:

our new analysis revealed the surprising result that Interdisciplinary journals utilizing Triple Anonymous review and Nontop Philosophy journals utilizing Double Anonymous review publish the greatest proportion of women authors overall. The low proportion of women authorships in journals using Triple Anonymous review in philosophy may have something to do with their being Top Philosophy journals rather than their review process.

What, then, explains the low proportion of women authors in top journals? Among the possible explanations offered as hypotheses for further investigation, the authors mention:

- “women are particularly hesitant to submit to those journals”

- “even with full anonymity, markers of gender, including the chosen topic of research, might still be available to referees and editors,” leaving opportunities for gender bias to operate

- “some suggest that men and women may have different views about what counts as valuable contributions to philosophy. So, if the editors and editorial boards for most philosophy journals are primarily men (at around 73 percent in 2010 according to historical data collected from the websites of journals included in this study), they may be more likely to reject work by women philosophers based on the topic, style of the writing, or citation practices”

- “there exists some evidence that academic writing produced by women academics is held to higher standards than that produced by men during the peer review process, even, it seems, when reviewed anonymously”

- “women are… less likely to coauthor than men, and perhaps coauthored articles are more likely to be accepted than single-authored articles”

The study is entitled “The Past 110 Years: Historical Data on the Underrepresentation of Women in Philosophy Journals” (it may be behind a paywall). Readers may also be interested in exploring interactive versions of some of the above data at the Data on Women in Philosophy website.

“In conducting their study, the researchers divided up philosophy journals into three categories: “top” (based on an informal survey at Leiter Reports),…”

I have a methodological objection.

There are some good objections to be had. But there’s no getting around prestige biases in the discipline. And we do glean some useful information when we divide things up this way. You’ll also see some clear trends regardless of how things are divided up. What’s the specific concern?

I can’t get past the paywall at the moment to check, but is one of the “possible explanations offered as hypotheses for further investigation” something like: “there are aggregate differences in quality between the submitted papers of men to top journals and submitted papers of women to top journals”? If not, it just seems a bit odd to not even flag this as at least a possibility worth considering.

Yeah, so, unfortunately, we’re not able to get enough submission data to do a comparison using the sort of analysis we conducted in the paper. This isn’t one of the hypotheses we consider, in part because there’s existing research in other fields showing a pretty big difference between the quality of work submitted by men and the quality of work submitted by women. Work by women is qualitatively better (at least on a somewhat standardized readability score and maybe some other measures – I don’t recall off of the top of my head). Women are also held to higher standards during the review process, go through more rounds of review, and ultimately take longer to publish, so the actual work that’s published tends to be qualitatively better (again, on an empirical measure that I don’t recall the full details of). We don’t know the extent to which this happens in philosophy journals, but it definitely happens in economic journals. Anecdotally, we’ve had editors tell us that men submit much less well-developed work than women (and probably submit more frequently as a result), but I don’t know whether this has anything to do with particular journals. If anything though, I would hypothesize (not speaking on behalf of my co-authors) that a partial explanation for the low proportions of women authors in the most prestigious philosophy journals is that women submit less frequently, in part because they tend to submit higher quality work and that just takes longer. This hypothesis is the most consistent with existing studies from other, nearby disciplines (as far as I’m aware).

That’s very interesting! The “readability” metric as a proxy for “quality” seems really weird to me, though. A lot of “quality” philosophy I can think of is (in)famously not super-readable. I get that it can be hard to develop empirical measures that distinguish “quality” between, say, a Kant and a someone-else, but, at least on my superficial understanding of these metrics, I wouldn’t think “readability” really tracks what I understand to be quality philosophy, and I guess I wonder what motivates conflating the two aside from just trying to operationalize things so they can be quantified.

Ah, I see. Yes, the sense of “quality” in play is certainly open to interpretation. Regarding readability, its fine if you’re opposed to this particular metric. On a personal note, I almost exclusively read philosophical research by women. Why? There’s a lot of content relevant to my work that I am slowly working my way through. If I have to choose between work that I can easily follow and work that I can’t, I will always choose the work that I can easily follow. I can read more of it, and I frankly just enjoy it more (remember when we read philosophy because its fun?). It turns out that work by women satisfies these conditions for me more frequently than work by men. I am also more likely to assign this sort of reading to my students. I’d rather they enjoy the content and understand it, than painfully slog through work they don’t enjoy, don’t understand, and won’t remember in 10 weeks anyway. Understanding “quality” in terms of content is problematic for several reasons that other researchers have already written about, so I’ll keep it short. Consider that men have set the agenda for what counts as “quality philosophy” for pretty much all of the history of philosophy. Its very difficult to imagine how we could use this as a metric without introducing some serious male-favoring bias. Same goes for whiteness and the Western tradition when we talk about “quality philosophy”. If the measure we’re using is “impact on the field”…well, obviously men will dominate on that front as well. Our paper shows that women were not commonly published before the 1950’s, and women didn’t really start earning PhDs in philosophy until shortly before then (if I recall correctly). So, what other measure should we be using? (I ask seriously.)

>So, what other measure should we be using? (I ask seriously.)

Definitely an interesting question! I don’t know how easily we can come up with some non-problematic empirical measure of quality in philosophical work– seems like there will certainly be costs with whatever is chosen. I guess I’d prefer something that took content more seriously though. Some of the best and most brilliant philosophy I’ve read (and even enjoyed!) was a real struggle to read through and understand– indeed, liming the contours of a conceptual space while trying to alter the scaffolding one is standing on might lend itself to some real difficulties in writing plainly.

If it’s hard because the ideas are hard, that’s one thing. If it’s hard because the writing makes it harder than it needs to be, that’s another thing entirely.

To my mind, a hallmark of “brilliance” is the ability to effectively communicate very difficult ideas. Form and content go together, and either without the other is worse off.

Definitely, and that’s usually my experience as well. I suppose, though, when I think of quality philosophy I think of things like creativity, novelty, rigor, importance, thoroughness, depth and other sorts of difficult-to-quantify properties. “Readability” is somewhere in there I suppose, but, I mean, in a certain sense, it wouldn’t surprise me if the average WaPo article scores higher in readability than the average PPR article, but one is philosophy and one is not.

In what sense is it “problematic” to consider quality as defined by the (male-dominated) field as a metric? The fact is that the field does have certain quality standards – whether or not they are the right standards – and it would be interesting to know to what extent women’s submissions satisfy these standards. If it turns out they satisfy the standards to a smaller extent than men’s submissions, that might be an additional reason to scrutinize these standards. But this may not be what we find.

As to what measure we can use: I think acceptance by journals is probably the best indicator we have of what the field considers high quality. So a measure could be the acceptance rates for top journals for women versus men (i.e., the percentage of submissions that is accepted). Such a measure could be biased, even with triple anonymity, if the text contains markers of gender – but no measure is perfect. If women’s acceptance rates are higher, that seems to be evidence for the hypothesis that women are more hesitant to submit. If they are lower, that could be evidence that they produce less work that the field considers to be “high quality”.

We’ve already had a bit of a discussion about submission rates and gender markers in the comments below, so I’ll leave it to you to take a look at that and decide whether its to your taste. Acceptance by a journal journal says that one’s paper was probably pretty good, but I rejection doesn’t mean that the paper was necessarily bad. (I have also seen some pretty cringe-worthy papers get through…) There are a lot of reasons papers are rejected by editors and reviewers that have relatively little to do with the paper’s overall quality. One of my papers was rejected on the grounds of that the word count was too high. I was subsequently told that the reviewer never looked at it and the paper was given a second chance. It wasn’t accepted, but its a clear case of the rejection having nothing to do with the paper’s quality. We see the same thing on the academic job market. There are many high quality candidates who do not get jobs. There are simply not enough jobs to go around. And with journals – there aren’t enough reviewers with enough energy to keep up with the sheer number of submissions. A lot of really good work will almost certainly get passed over. Regarding quality a la male agenda setting – other folks have written about this, and its not my area of expertise, so I’m not going to give a comprehensive answer here. I’ll say that the problem is a moral one. If men employ standards that somehow prioritise the work of men, then the standard is unfair. Where the standard impacts on a person’s livelihood, we’ve entered the domain of wrongdoing. The mere fact that the standard is one coming from a male-dominated field isn’t the problem, its that there’s a likely unfairness built into the standard. Some of this is empirically testable, and we will get there. There are relatively few people conducting empirical research on these (philosophy-focused) issues, so it takes time. No paper will be as comprehensive as we all want. But each new paper does help us figure out where to look.

>rejection doesn’t mean that the paper was necessarily bad.

This should be drilled into every graduate student from day 1.

Also: Don’t wait for people to tell you to do things (take initiative). Your department is not the whole universe (spend time working with scholars from other disciplines). And, you get plenty that you don’t ask for but rarely anything you want, so – ask, apply, submit, and advocate (and the like).

I agree that a rejection does not necessarily mean that the paper is bad, but why would that make acceptance rates (of men versus women) a bad measure of the average quality of papers submitted by these groups? Yes, if woman-authored papers are rejected more often for bad reasons than man-authored papers, that would make such a measure biased as a measure of quality. But is there any indication that this is the case? Whichever hypothesis explaining the top journal differential you are going to test, you will have to use measures that are possibly biased. So the mere fact that a measure is possibly biased doesn’t seem to be a very good argument against its use. Besides, even if the acceptance rate measure is biased against women, you might find that women’s submissions are accepted more often, in which case we have good evidence that women submit higher quality papers.

I can see that the quality standards might be unfair, I was just questioning why it would be problematic to measure the extent to which men’s and women’s papers satisfy these standards. But it looks like you agree that we should try to measure that.

I would think that readability is very likely positively correlated with being written by a native speaker. Hence, it seems to me that a readability criterion would be biased against non-native speakers, which might then have some unfortunate effects if applied as quality criterion.

This is a very good point. Thanks for mentioning it. Employing an objective measure of “quality”, that isn’t inherently unfair will be very hard (probably why we tend to assess papers across several measures – clarity, creativity, coherence, brevity, etc.). This is also a good reason for researchers submitting their articles to always feel a bit mistrustful of the review process, and for editors and reviewers to engage in personal reflexivity when assessing research.

This is a really interesting and important empirical study! Not to distract from the content of the post too much, but does this mean the ban on empirical studies has been lifted at Ethics?

For more on Ethics and their ban on empirical studies, see this.

We started the review process on this paper so long ago (maybe 4-5 yrs?) that I honestly don’t remember how we ended up getting this paper under review initially. I know, at the time, a lot of journals were commissioning empirical pieces (obviously to go through the fully anonymized peer-review process). In our case, I think we hard-pitched the sheer size of the dataset and the fact that we were working with two seriously experienced data scientists (we actually came up with a novel method for conducting two of the analyses – no small feat). But we also submitted to several other journals and were rejected, so I could be misremembering. You can always reach out to a journal editor to find out what they think, but I suspect it might have just been a fortuitous time to propose the paper (or something akin to that).

Thanks, Sherri! I guess we’ll just have to ask the editors to weigh in here. Editors: does the publication of this empirical study in Ethics mean the ban on empirical studies has now been lifted?

What sort of empirical work are you doing?

Some of my work in political philosophy involves analyzing polling data. Other empirical studies are a bit closer to what you’d expect from x-phi (surveys). Would be fantastic if Ethics is willing to consider the kind of empirical work you, I and many others in the philosophical community do!

It’s adorable that the article about what they are and are not looking for is behind a paywall. Moreover, they don’t provide a DOI. Ethics indeed….

What they DON’T want (from the article I linked to above): “5. We don’t publish empirical studies. Finally, I come to a more categorical point, of no use in revising any prospective contribution. We do not publish original empirical studies. A sufficient reason for this is that we lack in-house competence to review empirical studies. Of course, we are happy to publish articles discussing ethically relevant empirical studies, as we did, for example, in our 2014 symposium, “Experiment and Intuition in Ethics”; it’s only the initial publication of data that we don’t do.”

Looks like it is also stated on their information for authors page… which is something, I guess:

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/journals/et/instruct

It is viewable, but the process is unintuitive. Click the Gray PDF button on the right side of the screen (at least, that’s what it looks like on my computer). It absolutely does look like its behind the pay wall.

I should also say that the paper started out much less empirical but after 4 rounds of revision and 4-5 years(?) well, it evolved.

Completely understandable! That happened to me once as well. 🙂

Can’t help but wonder whether I should now submit my empirical work to Ethics. Seems like the editors are willing to consider empirical studies and, if anything, nudge authors to make their paper all the more data-driven in the review process! Could perhaps one of the associate editors confirm this? Getting mixed signals from the journal and not sure what to think anymore.

The bullet points at the end of this account illustrate succinctly the problem, seems to me. Terms like gender markers and gender bias continue the tradition of a male-dominated discipline. The fact of reluctance, on the part of female philosophers and public intellectuals., further exacerbates a difficult playing field. Charts and graphs are useful, I suppose, but to whom? I sometimes self-deprecate when writing to media, signing off as: A Midwestern Public Intellectual. There aren’t many here. But that’s another story…

I apologise – I’m not quite following the point. Is the idea that talking about gender contributes to a male-dominated discipline? Can you say more about that? I’m not sure I understand but I like to keep concerns of this sort in mind when writing. And reluctance about what? Re. charts and graphs – they’re actually more useful than the written text if you know how to read a graph, so, if nothing else, they help convey the information more quickly. If the point is really about the empirical analysis, it can help us figure out what’s going on so that we can intervene as a discipline where interventions are needed.

We didn’t want to be too uncontroversial 😉

Linguistics & Philosophy is definitely interdisciplinary, as the name already suggests…

The editors specified primarily philosophical topics when asked. The “Non-Top” philosophy category was for journals that significantly engage with philosophical work. Interdisciplinary journals were mostly journals that philosophers might publish in but mostly included journals that did not self-identify as primarily philosophy journals. In other words, the editors mentioned that they do publish some philosophical content but that that wasn’t the primary function of the journal. I understand why its confusing, but we just couldn’t come up with a better category name.

Just to make sure that I understand this: we begin decades ago with the observation that women’s publications tend to be underrepresented in the top journals. There are very many hypotheses that might explain that underrepresentation, some very sophisticated. One hypothesis is seized upon, perhaps plausibly: the hypothesis that male editors are bigoted against women’s contributions. More byzantine versions of the hypothesis follow, now including the extra hypothesis of unconscious sexism and even the hypothesis that female editors and reviewers have taken on the anti-female sexism imputed to the male editors and reviewers.

How can such a complex version of the bigotry hypothesis be tested? Fortunately, whether such bias is conscious or unconscious, it would apparently be ruled out by anonymous review. And this has now been tried. The results seem to be clear: at the top journals that mean the most to careers in the profession, the evidence points in exactly the opposite direction of what the bigotry hypothesis predicts. Even if that does not in itself refute the bigotry hypothesis, it certainly puts serious pressure on it.

This is so even if it turns out that the anonymizing is not entirely successful. Even if the reviewers and editors under the anonymized condition are somehow able to discern the sex of the writer half the time or even more often, whether consciously or unconsciously, one would still expect to see an increase in the acceptance rate of female-authored papers if the (conscious or unconscious) bigotry hypothesis were true. And yet, again, if I’m reading this correctly, this is exactly the opposite of what has been found.

Now, perhaps there’s some even more complex and byzantine, yet true, explanation for this finding that allows people to preserve the bigotry hypothesis. But isn’t the natural move here to take very seriously the possibility that the bigotry hypothesis is not the best one after all, and to explore other models? And yet, the main explanations that appear to have been considered here take the bigotry hypothesis for granted.

I suppose my question can be put this way: What reasonable falsification conditions are in play here? Or is this not meant to be a testable and falsifiable hypothesis at all?

Assuming this note is referring to content in the Discussion (which I believe is the only place bigotry is overtly addressed), its somewhat of a misrepresentation of the content. We do indeed discuss the bigotry hypothesis for one of our findings. Our concern is that there might be something specific about the topics, structure, tone, or some other features of the writing itself that is activating unconscious bias – of editors or reviewers. (We very much respect the editors of these journals and have been deeply appreciative of their contributions to this and related research). This is a testable hypothesis. Otherwise, the other hypothesis, which we haven’t had enough data to test, is that the low proportions of women are due to lower submission rates, esp. at the most prestigious journals. This comes up in regard to several different findings in the Discussion. And there’s some anecdotal evidence that this might be the case. Our main issue is that we need to compare submission data for each journal for each year while attempting to account for the time difference between submission and acceptance (it would be great if journals could track that info. and share it). If the low proportions of women in the most prestigious journals is primarily due to low submission rates, then there’s a good question as to why. Maybe women and other folks are simply afraid that their work won’t be accepted, which would actually make sense given the historically low numbers of women published in these journals. If that’s it, then this hypothesis is both testable, and, we could potentially run an intervention study to see if it make any difference to the proportions of women accepted and published. And, by the way, we bring up some of these bias related concerns because people ask about them. Notapostgrad had a question that directly ties in to this issue, as considered in the Discussion.

Thank you for your reply. I remember, some years ago, that Dicey-Jennings crunched the numbers for us all and it was seen (if I recall correctly) that women entering tenure-track positions tended to have fewer publications at the time of hiring than their male counterparts did. If that’s true, then might that present an alternative explanation to the fear hypothesis? In a time of a very stressful and worsening job market, one might imagine that any subset of the applicants that might be expected to have more publications would tend to be more zealous in submitting articles.

Also, my use of the term ‘bigotry’ was meant to include unconscious bias, at least in the way I understand you to be using the term in this response. Like some others here, I can’t get past the paywall to read your article; but I’d be interested in what you would consider the falsification conditions of the union of the bigotry and unconscious bias hypotheses.

I propose the fear hypothesis because I have had a number of conversations indicating that there are plenty of people who do not trust the most prestigious journals to publish them. Anecdotal but suggestive.

You might be right re. Jennings’ data. After looking for a bit, I couldn’t find anything related to the number of publications and the gender of hires. She has shared such a wealth of information that I could have missed it. I’ll note that, as Jennings’ was collecting this data, there was also a massive push to include more women in the discipline, so it could be that hiring committees had changed their hiring strategies. I don’t really believe there are any “women’s topics”, but advertising positions with AOS requirements that women were more likely to satisfy would certainly boost the number of women qualified for those positions. It could be that, relative to the qualified applicant pool for more specialized positions, women and men had roughly equal publications. I have no idea, but you probably get the point. I also don’t know if your suggestion (even though its definitely worth considering) explains the historic behavior of journals. We also don’t have enough accessible information to test it (or so it seems). (As an aside, even if women are hired with fewer publications, women do not, historically get tenure at the same rates as men. Which might actually make sense on your hypothesis. But, there’s also a lot of good evidence that women are held to much higher standards than men when up for tenure).

Re. bigotry: Well, the hypothesis we’re considering is that there’s something about work by women – topic, tone, structure, word choice, whatever – that potentially activates unconscious bias. To figure out whether there are any such differences, any that could contribute to this result, we’d probably have to take some sort of machine learning approach – LDA topic modeling, sentiment analysis, etc. I doubt a person could process enough information to reliably test for a difference. I’m working on this right now.

Thank you.

I don’t track this data as well as I should, but I think the person you are replying to is referencing some of the data that Jennings discusses here:

https://philosophysmoker.blogspot.com/2012/04/to-get-job-in-philosophy.html

and then again here:

https://www.newappsblog.com/2014/12/gender-and-publications.html#more

I believe the data initially suggested that women have half as many publications as men for TT job placement (again, I’m not putting in the effort to really carefully put the claim). And then, as you can see from the second link, this sort of take-away was called into question. I’m almost certain there was a discussion about this sort of thing in dailynous, but I can’t find it at the moment.

First a disclamer that I didn’t read all the posts here. Wouldn’t a simple yet plausible explanation be that women produce fewer quality work? Of course, I am not suggesting anything silly like we are less smart on average. But I feel that women face on average more distractions in their life (like kids), and I wouldn’t be surprised if that undermines the quantity of quality work women are able to produce.

There are two ways of interpreting this hypothesis. The ungenerous interpretation is that research by women is of lower quality, so there is less high quality research by women. The generous interpretation is that women produce less research, so there is less high quality research by women. The former is unlikely, and we have already talked a bit about measures of quality above. Feel free to take a look. The latter claim is plausible. And the reason you suggest has previously been hypothesized. That women produce less research because they are overburdened with service work, family commitments, etc. Above, I also noted that it could be that women produce less research overall because women produce higher quality research, which takes longer to submit. And also that women tend to be held to higher standards than men. Either could reduce the quantity of high quality research articles produced by women. (Again, we talked about this above). Looking at submission rates would also help figure out what is happening. (Also discussed above).

A non-philosophical empirical example – a research institute increased the proportion of papers accepted by high Impact Factor journals by a publication bonus tied to IF. The model was that authors were not bothering submitting to prestigious journals as acceptance rates were so low, and possibly perceived turnaround time for rejection and re-submission elsewhere too long. So definitely need submission rate data to correctly interpret.

I would also say that this assumes that journals that report blind review are really blind, which is not the case.

I am surprised by the fact that for top journals, the proposition of articles by women *increases* when submission is non-anonymous. I can’t find anything in the blog post or the discussion commenting on this: what are some of the hypotheses here?

It would seem to me that this puts into doubt the second hypothesis in the blog post, that even with full anonymity there is an unconscious gender bias. If that were true, than I would expect that the bias became more pronounced when submissions were non-anonymous, because there are more gender markers available in that case.

Perhaps when reviewers know the gender of the author they try to conciously correct their implicit biases? If so, perhaps a policy of more non-anonymous submissions would favour women in the profession? I find this very counter-intuitive, so I’d be curious to hear alternative explanations!

For more on the relationship between anonymous vs. non-anonymous submission and the proportion of articles by women, I was very impressed with the statistical analysis that Jonathan Weisberg reports here:

https://jonathanweisberg.org/post/A%20Look%20at%20the%20APA-BPA%20Data/

I expect it is largely due to the fact that some use special issues and invited submissions to increase representation (or at least pay attention to it then). Also in an earlier study it was quite clear that the Proceedings was driving the results (not sure here but perhaps Sherri can review)…

Hi!, I think I’ve read all the comments here, but still have some questions about the “alternative hypotheses” mentioned above (i.e., ones other than systemic bias or bigotry as being able to explain the documented phenomenon).

A couple of those mentioned are in the ballpark of “well, what if women do less good research?” as being able to explain the difference. I’m not remotely sure how to think through that one, but don’t think the “readability” point SLC makes gets us very far. Regardless, set that one aside. What about stuff like:

Thanks for sharing this research!

I have been thinking about some additional hypotheses. I’m not saying any of these are true or plausible, but they might be worth investigating. Before we do that, however, I think it’s important to have some measure of the quality of papers submitted to top journals by women (see discussion above) to get more information. It is perhaps too early to investigate why women produce fewer top-journal-meriting papers when we are not sure whether that is the case. In any case:

Well, it may be that some of the smartest women see how unlikely (statistically) they are to succeed or don’t like how they are treated and go elsewhere too. My guess though is that those who do stick are highly intelligent (smarter men could also do better in many ways to choose a different career and may have more pressure to do so given prevailing social mores in many countries).

“Maybe women don’t care as much about academic research as men?…”

How incredibly patronising. We care just as much as you do, mate!

One might argue that we care *more* than many cynical careerist JAFWMPs (“Just Another…”), because we choose to wade through so much more sh*t in order to make our contribution to this discipline that doesn’t seem to really care about remedying its obviously massive gender imbalance in opportunity and access to resources.

The empirical claim to investigate wouldn’t be whether some women care as much about academic research as some men, but whether, on average, interest in academic research varies across gender. It’s not patronizing to consider an empirical hypothesis (which, of course, could be false): part of the challenge with this discourse is us being able to ask serious questions without being caricatured on blowback.

“The empirical claim to investigate wouldn’t be whether some women care as much about academic research as some men, but whether, on average, interest in academic research varies across gender…”

Why on earth would you think that it might? How self-serving of men, as a class, to imagine that the reason women are not achieving recognition in Philosophy at anywhere near the level of your good selves might be not due to your own treatment of your female colleagues, but because female philosophers are simply a different kind of creature – a creature with other, less intellectually intense, interests. Such as baking perhaps? Child-rearing?

I’m sorry that you feel you’re being caricatured – not a nice experience, is it?

One reason to think there might be general gendered differences in interest in philosophical research is that there is already a robust and widely recognized research program illustrating general gendered differences in interests across professions. It’s summed up in the research slogan “men prefer to work with things, women prefer to work with people”.

This is not news, and research on academic philosophy already suggests that interests are playing some role in what we see. Morgan Thompson and her colleagues, for instance, have produced research showing that the biggest drop-off in the representation of women in philosophy occurs at the end of the first undergraduate course — not at the job market, or in PhD admissions, or in the decision to major, but in the first course. And by comparing psychology with philosophy, Katharina Nieswandt and Ulf Hlobil found that women tend to prefer psychology as more empathic, less combative, and more likely to allow for financial security and the ability to have a family than philosophy, which is viewed as more systematic and combative, with less opportunity for financial security and a family.

So I don’t think we should rule out the possibility that there might be general gender differences in preference concerning philosophical research, just as general differences in preference may explain at least part of the underrepresentation of women in fields like philosophy and engineering, and their corresponding overrepresentation in fields like psychology and the social sciences. That doesn’t mean other explanations shouldn’t also continue to be investigated, of course. And I’m in favor of making the discipline more welcoming to people who might otherwise prefer to do something else with their time. But we should also bear in mind that a widely established hypothesis investigated for decades may be worth considering as well.

Thank you for the considered reply, Preston. Here are a few thoughts in response:

The “widely established hypothesis investigated for decades” that you cite is: “men prefer to work with things, women prefer to work with people”.

To put it mildly, this strikes me as an exceptionally broad hypothesis. I wonder to what extent empirical work might rigorously verify or falsify it. Can you point me towards at least some of the studies you have in mind?

Secondly, even if this were true, why wouldn’t it make philosophical research *more* suited to women and less to men? Philosophy used to take as one of its major concerns how we should live – ‘we’ being people. To the extent that the purview of philosophical research has shifted to become more ‘thing-oriented’, *by your own hypothesis* this could represent men taking over our discipline in a self-serving manner and narrowing it down to their own thought-patterns and interests.

As it happens, I do suspect that something like this has occurred. In which case, that women’s relative disinterest and disadvantage in intellectually navigating this ‘desert of reificiations’ should be taken to show that we are temperamentally ill-suited to, or disinterested in, Philosophy per se is quite the disingenuous sleight of hand.

John Light’s airy hypothesising above seemed to me to help bring about such a sleight of hand (albeit most likely not deliberately). That is why I reacted so negatively in my first response to him.

Hi Professor Apricot. That is definitely an exceptionally broad hypothesis, but I characterized it as a research slogan! And as a good slogan should be, it’s punchy enough to give the gist of it. Also, while I can appreciate a concern that someone might be engaging in the sleight of hand you say motivated your response to John Light, I think he’s pretty obviously correct that responses like this prevent us from talking about hypotheses that are, apparently, still live. And I don’t think we have enough evidence to rule these hypotheses out. If that’s right, then it doesn’t help the situation to respond to them with caricature and condemnation.

But you’re certainly right that as a hypothesis that slogan doesn’t give much to go with. Here’s something more representative, from the abstract to “Men and things, women and people: a meta-analysis of sex differences in interests” by Rong Su, James Rounds, and Patrick Ian Armstrong:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19883140/#:~:text=Results%20showed%20that%20men%20prefer,on%20the%20Things%2DPeople%20dimension.

You should also look up the work from Thompson, and from Nieswandt and Hlobil. Nieswandt and Hlobil’s data is particularly valuable, as they directly compare interests across psychology and philosophy (Nieswandt has a good write-up of the significance at the APA blog). It looks like one explanation for why more women tend to major in psychology over philosophy is that they have a set of preferences and true beliefs about what psychology and philosophy are like. That’s not to say we shouldn’t try to change one or the other discipline to fit with the interests of those who might currently like to do something else. but it does put pressure on the suggestion that systematic injustice is the best explanation for what we see.

And is it really that contentious that women might, in general, tend to prefer some kinds of professions and men tend to prefer others? After all, there’s some evidence of sex-based differences in preference in human infants at 18 months of age, where girls prefer to play with dolls and boys prefer to play with trucks. I’ve had some people tell me this is all the more reason to start social engineering programs in infancy, but that difference in preference has been found in chimpanzees and bonobos as well. Again, this doesn’t say anything about where philosophy does (or should) fall with regard to one side of these divides or another. But it does illustrate the need to be more careful in how we treat (those who raise) these hypotheses.

I’m surprised that this kind of research isn’t more widely known. In my experience, it’s not that people are familiar with it and have a settled view; they tend to have no idea it’s out there. And that’s part of the problem, it seems to me. So I don’t think it’s a good idea to respond to suggestions like Light’s with the presumption that men are “self-serving, as a class”, and to speculate that anyone who brings this up is committing some kind of social or political sin.

Hi Preston, thanks for the links, I’ve just had a quick look at the metaanalysis, but it’s behind a paywall for me. But from the abstract, it seems that the term ‘interests’ leaves open whether what is purportedly shown is that women have greater innate propensities to focus on people rather than things, or whether this is an effect of female socialization (which I can attest can be quite savage). Therefore I suggest that this result is of limited value as an exculpation of an overwhelmingly male discipline for supporting so few female colleagues within its ranks.

And moreover, as I mentioned above, *even if we grant that women do have greater innate propensities to focus on people rather than things*, there remains the issue of whether male philosophers have hijacked the Philosophy discipline towards a gender-contingent thing-obsession, and away from its potential for generating humanistic insights, if its female scholars were listened to more. If so, what a loss that would be, but in picking up many of the most lauded contemporary monographs, one suspects that it might be the case.

My charge of self-servingness may seem confronting, but have you considered how disrespectful it is in a ‘game of giving and asking for reasons’ to tell your interlocutor that you consider their own class to be necessarily a more minor player *in the game itself* than your own?

Hi Professor Apricot. Thanks for the reply, and the ongoing dialogue. I’ll try to scare up a copy of the essay and send it to you. Concerning your hypothetical interpretation, based on the abstract, it’s certainly possible that women’s interests are due to socialization — although keep in mind that we see the largest gender differences in occupational choice in the most egalitarian societies (e.g. Scandinavia), and the smallest difference in the least egalitarian societies (e.g. the USSR). This at least suggests that when you allow people to do what they want, men and women tend to want different things out of their careers. Also, I take it that there’s little go to the thought that female and male chimpanzees and bonobos prefer to play with, respectively, dolls or trucks because of socialization pressures.

At any rate, to focus on this possibility is already to move quite far away from the condemnation that John Light’s suggestion was met with, which was my point. And there’s an established body of research that’s already looking into differences in interests that appear to be present across the sexes. So it seems to me that people ought to be more cognizant of this literature.

And recall the data from Thompson, et al., and from Nieswandt and Hlobil — it looks like women are less interested in philosophy from the very first course, and that they generally have preferences and true beliefs about philosophy and psychology that make it rational for women to tend to prefer to major in the latter over the former.

Having said that, it’s of course possible that self-serving men are systematically excluding women from the profession, and distorting its focus in doing so. Personally, I think it would be great if everyone was interested in philosophy, and one of my projects is to introduce philosophical instruction and study into pre-college courses, with the hope that this might be good for both society, and the profession. But again, at this point we’re quite a ways away from the kind of response that led to my intervention.

Finally, in your last paragraph you write “have you considered how disrespectful it is in a ‘game of giving and asking for reasons’ to tell your interlocutor that you consider their own class to be necessarily a more minor player *in the game itself* than your own?” We’re friends, I hope, and I’m not sure whether this was meant to be directed at me in particular, but I’d like to take issue with a few things here. First, I think it’s important to be careful about how we phrase what we say when we accuse other people of wrongs like disrespect. And when the accusation comes by way of attributing claims to them, we should be sure to use the language they used. I have tried to be very careful about what I’ve said here, knowing the way these conversations sometimes devolve. And I did not say anything about women being “necessarily a more minor player” in the game of giving and asking for reasons. I’m not even sure what it would mean to say any class of people was necessarily a minor player in some human activity (with the exception of cases like weight classes or age-based differences).

What I said, and which I stand behind, is that it may be that men and women tend to have different preferences — about occupations and life goals — that goes some way toward explaining why there are more men than women majoring in engineering, mathematics, physics, and philosophy, and more women than men majoring in psychology, social science, and nursing. There is nothing disrespectful about that. The fact that men and women might tend to have different preferences says nothing about whether any one set of preferences is “better” than the other. And the fact that men and women might tend to have different preferences does not mean that there is anything wrong or defective with the exceptions — we are creatures of Spirit as well as Nature, after all. Perhaps some people would make those inferences, but I should think it’s clear that I haven’t.

Okay, now I want to address your second point. And thank you for the chance to talk a bit about this. It’s helped me clarify some of what I think, and I hope it presents a perspective worth taking seriously.

To be clear, concerning sociological explanations for the current shape of the profession, I leave open that the “self-serving men” hypothesis is still worth investigating. Do you know of any evidence that supports it? From the data I’m familiar with, the preference-and-true-belief explanation has more going for it. So sure, your hypothetical is, so far as I know, still a live option. It’s early days for this research. But I think it was Dewey who said that a doubt has to exert some force on us before it can merit consideration. You know I love ya, but without good reason to think the “self-serving men” hypothesis is liable to be right, I’m worried we’re left with no good reason to continue to act (or speak) as if things can be explained by appeal to self-serving men.

Notice, this has important implications for how to increase the representation of women in philosophy. If it tends to be the case that most women would prefer to do something else, but that some find (or would find) the discipline appealing, then we need to present an accurate picture of the field so that women (and men) can make informed decisions. This is because we want to both avoid running off people who might be interested, but are presented with a caricature of the men in the field as self-serving (or what have you), and to avoid downplaying differences in, e.g., philosophy and psychology concerning the place of empathy, systematicity, financial security, and the ability to have a family.

For what it’s worth, when it comes to sociological explanations of this sort I think people like Greg Frost-Arnold, Kevin J. Harrelson, Joel Katzav and Krist Vaesen, and Adam Tamas Tuboly have done a lot to illuminate how the profession came to take the shape that it did in the Anglophone world over the last century. Katzav and Vaesen, for instance, detail the journal-capture of Phil Review, Mind, and The Journal of Philosophy by analytic philosophers in the middle of the last century, pushing out the pragmatist-inflected pluralism that was then dominant. It’s pretty eye-opening, and it makes you wonder how much of that kind of behind-the-scenes implicit agreement, and practical coordination, still works to systematically exclude certain perspectives from the profession today. It needn’t be intentional, or even all that conscious. But it doesn’t much for a dominant ideology in a field to push out heterodox voices, and if enough of an organization’s institutions are captured by a given ideology that can have a lasting effect across a profession, with very little conscious effort required on the part of individuals.

Hi Preston, thanks for this too. I agree that it feels good to really thrash out the debate between strongly opposing positions in a forum such as this, rather than engaging in the self-censoring which seems increasingly needful in these days of social media cancel culture…

What evidence do I have that men in professional philosophy are self-serving re. acting to redress the really significant gender imbalance that we have? I open my eyes and look around me. In so many places, I see narcissistic mentoring. I see men promoted over women who have objectively better work performance on a host of measures. I have been that woman. I have sat in a meeting and watched a Head of Department swear blind that he would have LOVED to appoint a woman in his latest hire but very unfortunately, “no women applied”. And I thought – that’s funny – I applied for that job. I’ve seen incredibly poor behaviours by men going unremarked because they’re ‘rock stars’ (whatever that means). I’ve seen talented women – who are real survivors and make an enormous intellectual contribution – gossiped about and professionally undermined in countless settings. Not to mention that sexual harrassment in this profession has a body count.

For issues of defining our values and best practice as a profession, I would suggest that phenomenology can trump citations of APA PsychNet. “Here is a hand. And here is another hand…” (Thank you Colin! :-\)

p.s. I appreciate the analyses of Katsav et al, and this is actually the kind of mechanisms I’m talking about too…

You raise some thorny subjects here, Professor Apricot, and I’m not sure how best to try to weed through them. I agree that issues of atmosphere, and respect toward women, are concerns that need to be taken seriously. And I appreciate your first-person reports. Still, I’m reminded of the old saw that “the plural of anecdote is not data”, and I was hoping for quantitative data, as I wish we had more quantitative data on just how prevalent these problems are. Given their nature, that may not be possible. So it may be that anecdotal evidence is all we’ll be able to go on (in which case perhaps I should mention, as one of a number of examples like this, that a non-philosopher at a University I applied to this year told me, about the department I was applying to, that “it is widely acknowledge that the department needs more women and minorities”).

And it’s worth noting that all of the quantitative data I’ve seen — some of it publicly available, and some of it not — suggests that if there’s any bias in hiring, it’s not in favor of men (the APDA has done some work on this). But this data is often difficult to get hold of, and it’s only recently begun to be investigated, so hopefully we’ll have a better view of things in the future. I know that I would have made some substantially different decisions while I was in graduate school if I’d been aware of some of what I learned only after graduating. That’s not to minimize the issues of atmosphere and respect you raise, but only to note that there is some evidence that the profession is actively trying to address the situation, at least on the job market.

So I think it’s important to try to model good interactions with one another, to permit frank and sometimes contentious exchanges about these issues, and to do so publicly. That can be difficult to do, given that we all have so much invested in the profession (“the debates are so fierce because the stakes are so small”, if you’ll allow another old saw). But if we work at this more concertedly, while striving to be guided by the better angels of our nature, then hopefully it will be easier to make progress on these issues going forward. Once again, I appreciate your taking the time to do that here.

Or you could just say “I’m sorry”.

Agreed. There is always the double duty issue and lack of appropriate family leave (at least in the US at many institutions) to account for…

I emailed Frank Perkins, editor of Philosophy East and West, to get his take on that journal’s submission, acceptance, and publication rates by gender. (I’ll add that I would be interested to compare data for the other top journal in my field, the Journal of Indian Philosophy, but it is not included in the Ethics paper.) Frank has given me permission to share the below:

This information doesn’t answer the question of why there are differing submission rates between men and women in the fields covered by PEW. Perhaps knowing the demographics of these fields would help understand whether the submission rates are roughly representative. My impression of Indian philosophy, for example, is that it has been perhaps even more male-dominated than philosophy as a whole, though I believe that is shifting in the past several years. And this is only an impression, not anything more substantial.

Finally, I cannot speak for Frank on any of the data above. I’m a book review editor at PEW, and can only speak to that data (which I haven’t included because I think it’s probably not at the top of anyone’s concerns–though I am happy to share the numbers if anyone wants).

As the paper notes there is a derth of data on this – we asked all the editors to share but got just a few data points. We believe it would be good for journals to collect data, set targets for improvement, and monitor performance if they want to promote equity in the field. Hence the good practices suggestions at the end of the paper.