Creativity and Pluralism in Philosophy

“Philosophy at its best is a kind of intellectual exploration, and the more methodological and stylistic constraints are placed on it, the less well it will function as such.”

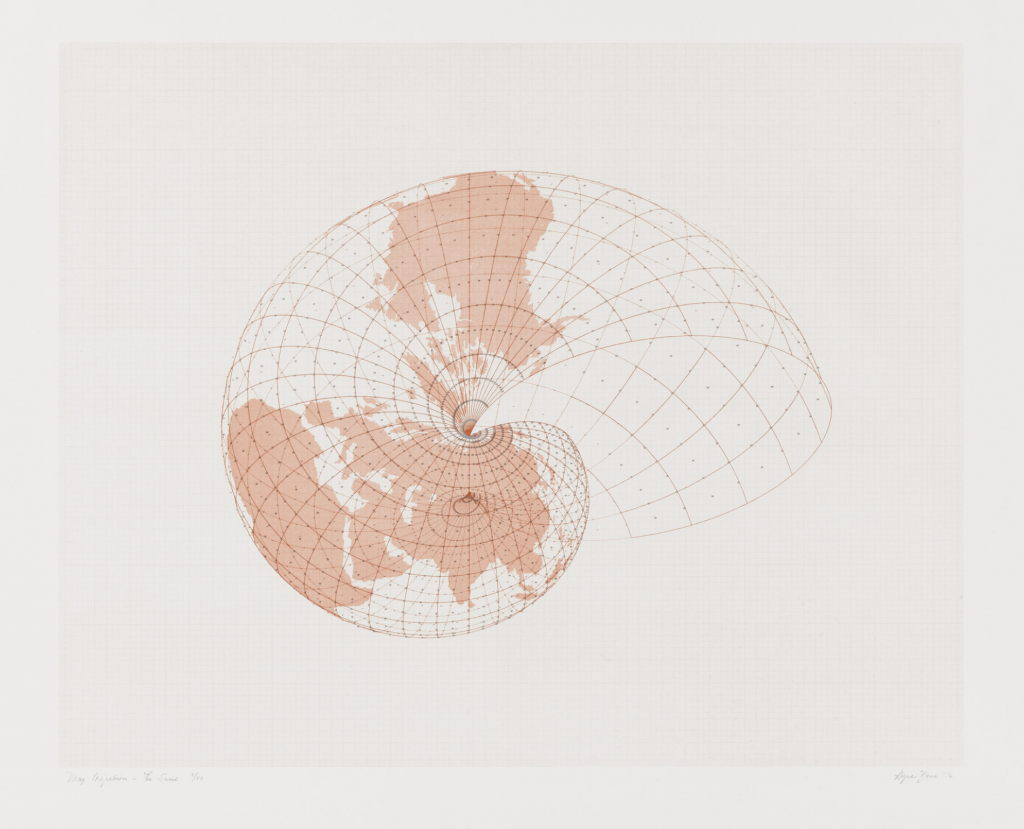

[Agnes Denes – Map Projections – The Snail]

My conception of philosophy is methodologically diverse and multidisciplinary. Philosophy can be and is done in numerous disciplines. I’ve explained before in some of my work that I see philosophy ideally as a kind of “research and design” wing of the academy. Part of what enables us (ideally at least) to generate knowledge is a lack of strict methodological constraints. Philosophy at its best is a kind of intellectual exploration, and the more methodological and stylistic constraints are placed on it, the less well it will function as such.

I think we sometimes try too hard to be like lucrative and currently more socially valued disciplines such as the physical sciences. But the methodologies of the physical sciences, while absolutely necessary for those fields, are not… well-suited to broad intellectual exploration, any more than following a map is well-suited to exploration of new land. In the physical sciences, we are looking to produce knowledge within defined parameters and methods that we’ve accepted as generating certain kinds of knowledge. It goes without saying that such methods are not much use when applied to themselves, when applied to thinking about what kinds of knowledge we should aim to produce or even what knowledge is. It’s like trying to use the rules of chess to think about whether we should play the game of chess, what variants of chess we might play, and the nature of games. To think about those things, we have to be able to set aside or operate outside of the rules of chess, and if we turn around and create new chess-like rules to govern our thinking about variants and why we play, then only certain predetermined kinds of answers will be possible, and we limit ourselves from the beginning.

Philosophy has the power it does (again, ideally) because it is not so methodologically bounded. We would be well served, I think, by emphasizing creativity as one of the defining features of philosophical thought, rather than technical facility or the oft-used yet hardly ever defined ‘rigor’, which seems nothing more than a euphemism for adherence to a particular style of writing and speaking that heavily leans on and tries to copy STEM fields. I’ve always been of the mind that one should never just try to copy someone else’s style or strengths. Discover and then do what makes you unique and valuable in a way no one else can be. We could be encouraging new and different things that offer something that you truly can’t find elsewhere, but we often are not. I started my academic life in physics. Physics is a wonderful and worthy field. But the world already has physics. It doesn’t need us to be physics. It needs us to be something different.

Though I think things are (slowly) improving, and are maybe a bit better today than they were when I started my career, we still quite often bind ourselves like this with strong methodological constraints, and thus weaken and limit what philosophy can do. Sometimes this is a conscious choice aimed at positioning ourselves within the academy—but when it comes down to it, we’re not going to justify our existence by being bargain-basement STEM. Most universities already have real STEM, so why do they need us? Not only is philosophy more valuable in the “big tent” methodological sense, but that’s also ultimately the way I think we have the best chance of survival and retaining an important place in the academy.

An appreciation of the diverse approaches to philosophy is something to keep in mind when discussing philosophical traditions with which one is less familiar. McLeod, an expert in Chinese philosophy, warns:

In general, I think that when we make claims that entire philosophical traditions of enormous parts of the world, like that of China, manifestly represent a single side of a divide that is recognized in the West or elsewhere, we’re basically always wrong. If there are naturalists and non-naturalists in Western philosophical history, why should we not expect to see this elsewhere in the world as well? The presumption should always be that a tradition included a diverse array of views, and the argumentative burden should be on one who wishes to make the claim that a tradition doesn’t include such diversity but represents only one philosophical position. Of course, much more can be said for my case than this, but fortunately one who insists on philosophical diversity within a tradition has a much lighter argumentative burden to bear than one who denies such diversity. All I have to do is show that particular views are *there*, not that everyone holds them, while my opponent has to show that *no one* in the tradition holds certain views—something they certainly cannot do.

The whole interview is here.

My word. Yea, not that this writer “stole” cause original ideas are quite rare these days; still happening everyday (maths yall).

Chomsky was saying these things in the mid 90s, and early thousands.

As well as entirely ignoring post-structuralism, and the majority of recent epistemic work.

Thanks for sharing

I agree that creating ‘new rules for chess’ only creates limits to what is possible, but one cannot be creative without creating these new rules. The problem is not the limits that are engendered, but rather the lack of agnosticism with regards such rules and limits: we need to be infinitely agnostic. If we managed to create a new epistemology, for example, it itself would of course be transcended some day.