How Philosophers Respond to Objections

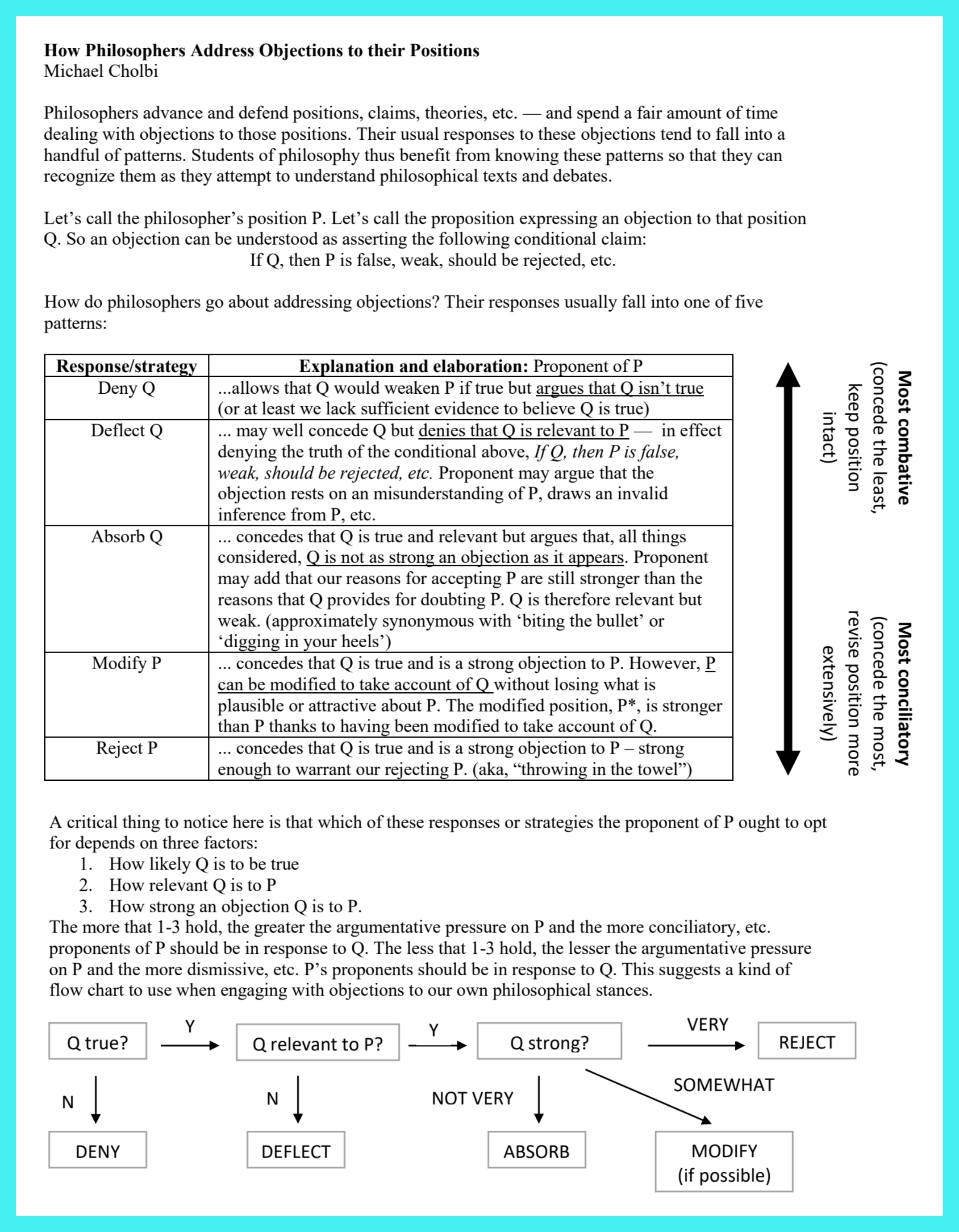

Michael Cholbi, professor of philosophy at the University of Edinburgh, has put together a useful handout for students and others interested in philosophy about the different ways philosophers respond to objections.

It seems like figuring out how to respond to objections is something students tend to need help with, and I think laying out the range of strategies is useful for them and anyone interested in how philosophical argument proceeds.

Professor Cholbi kindly gave me permission to share the handout here. He acknowledges it is not an exhaustive list.

The handout is also available here.

Suggestions for additions to the list of response strategies are welcome.

This looks helpful as a way of mapping out logical space.

I think if I were to adapt this for my own teaching use, I might break things up a bit differently, talking a bit more specifically about what kinds of strategies one might use to deflect or absorb.

For example, here is a kind of move that is common and interesting and good to communicate to students, but that fits slightly awkwardly into this schema:

“The objection you have raised does represent a serious challenge, and I don’t know how to respond to it, but let me explain why it is an equally good objection to every serious alternative to my view, too. So while this is a problem, it’s everybody’s problem.”

I think this fits somewhere in between deflection (it’s not relevant to P *in the particular context of this dialectic*) and absorption (I agree that it’s a problem but let’s not get hung up on it here). But it’s quite unlike “biting the bullet”.

I agree with you. Generally, I like the handout. Particularly, I wish it was more accessible; provides examples of how students can *phrase* such a response to each objection.

Ex: “This objection is legitimate if it could be argued that Y. However, there is reason to doubt Y because of Z.”

This response puts the burden of explanation/argument BACK onto the objector(s). Objectors, are, after all, either real or hypothetical interlocutors with their own arguments too.

This strategy is a third-order thinking approach: objection to objectors’ objection while providing objections/doubt about the success of the objector’s possible explanation in support of their objection to you.

This kind of thinking takes lots of skill though. As Kant would say, such is the restlessness of reason.

Why wouldn’t this just fall under the deflect strategy? If Q really is everybody’s problem (equally), then it’s not relevant to the truth of P, right?

This is great. But it has philosophers always affirming or denying (i.e. denying that Q; affirming that Q is relevant to P; and so on), so it omits responses involving the withholding of judgment. Some sometimes withhold judgment regarding whether Q (e.g. when the objection depends on a possibility they hadn’t yet considered). This is more likely to occur in talks than in print in my experience.

Very useful Michael… I’ve often wondered how best to respond to comments/questions/criticisms on my PowerPoint presentations.

Now I know!

I imagine this handout — or this type of handout — could prove pretty useful in other disciplines as well, say law and rhetoric, and indeed anywhere where people take arguing seriously. And the combative/conciliatory scale helps clarify the reception that various strategies may invite. Cheers, sj

How about ‘flips Q, showing it to be a point in favour of P rather than an objection’? That would appear to be even more aggressive than denial.

This handout is fantastic, and so are the comments! I teach a unit on “dialectic” in my critical thinking class, and handouts like these are invaluable. Thank you.

Maybe I’ve been working for too long outside the orbit of philosophy proper, or perhaps I was too much steeped in Continental traditions in my early years, but this strikes me as an especially desiccated collection of possible responses. All of them assume strictly binary logic and an all-or-nothing, polemical approach to argumentation, in which P must either emerge victorious or go down to bitter defeat.

Here are a few other possibilities:

More fancifully, one could borrow some licks from Billy Collins:

I jest, and yet there can be something philosophically powerful in a playful and imaginative engagement with P and with Q.

In the Modify P section, I find it strange to describe the modified position P* as stronger than P. Certainly we do not want the new position P* to be logically stronger than the original position P, in the sense that P* implies P, since in this case objection Q would apply just as much to P* as to P, if not more so. Perhaps what is meant is that the new position P* is stronger in that one can defend it more easily or more successfully than the original position P, because it is no longer open to objection Q. But this occurs, of course, precisely because P* is in part weaker than P, rather than stronger. Do we want to say that one is placed into a stronger position philosophically by holding weaker claims? I would say instead that one is stating a weaker claim and thereby holding a weaker position.

This handout advances philosophical argument rhetorically by adding an acknowledgement of the element pathos via the combat-concilliate spectrum. It fails to integrate ethos, however, which operates counter to this model. The logos of ethos locates strength in flexibility and integration. So the more P can tolerate Q the less insular and rigid it is. This acknowledgement would go a long way to encourage the capacity of philosophers to engage productively with other humans and restore trust in critical conversations: the possibility that persuasion can be reverse engineered from truth and character, rather than the other way around.

Another response is comparative rationalisation. If Q is true, and the argument is that Q is validated by XYZ(facts that establishes fundamental opposing arguments in relation to P). X might validate Q but perhaps only under YZ conditions and the same for Y and Z respectively. Q as a rational argument is therefor dependant on external factors relevant also to P and only within the framework of comparative analysis. P may then be evaluated against XYZ to establish perspective for argument. If XYZ does not exist Q has no frame of reference in sustaining rational opposition. Identifying XYZ is therefor a means of comparing similarities and differences between P and Q viewed against a common background and based on merit of relevance may validate one, or the other, or both perspectives.