University to Faculty Concerned about Covid: “Beg”

“We are discouraged from “sharing Covid data that is not related to the course.” Presumably, nattering on about the state’s overburdened hospitals, worn-down physicians, and increasing death counts might constitute “pressure,” and faculty “should not pressure students to get vaccinated or wear a mask.” The most we can do is “encourage.” In practice, these guidelines have left faculty proffering details of their personal lives to crowds of unmasked students. We have become beggars and supplicants, hoping for mercy.”

Those are the words of Amy Olberding, Presidential Professor of Philosophy at University of Oklahoma, writing in The Chronicle of Higher Education about the University of Oklahoma‘s complete and utter failure to take even minimal precautions to protect its faculty, staff, and students from COVID-19.

She says:

This first week of fall semester, my colleagues are out making the rounds, meeting their classes for the first time and, this year, telling stories about their own lives. One professor speaks of her baby, too young to vaccinate. Another mentions an immunocompromised spouse at home. Still another tells of a sibling, lately deceased from Covid. Though each tale has its own rhythm and tone, they tend to end alike: Faculty nervously offer masks to their bare-faced students, who mostly decline to take them. Some look away sheepishly, some placidly stare, some sneer. Then class as we used to know it must begin, with introductory tours through syllabi, requirements, and course aims…

At the University of Oklahoma, located in a “high risk state“:

- Students are not required to wear masks in classrooms or other indoor spaces

- There are no signs encouraging students to wear masks

- Faculty are prohibited from providing incentives to students to wear masks

- Faculty are officially discouraged from structuring in-class group work in a way that attends to who is or is not wearing masks

- Students are not required to get vaccinated

- Students are not required to notify their professors when they contract COVID-19

- Free on-campus COVID-19 testing has been eliminated

- There apparently is no “surveillance testing” of students for COVID-19

- “The university holds public events where unmasked administrators lead hundreds of unmasked freshmen in yelling out the school’s spirit chants”

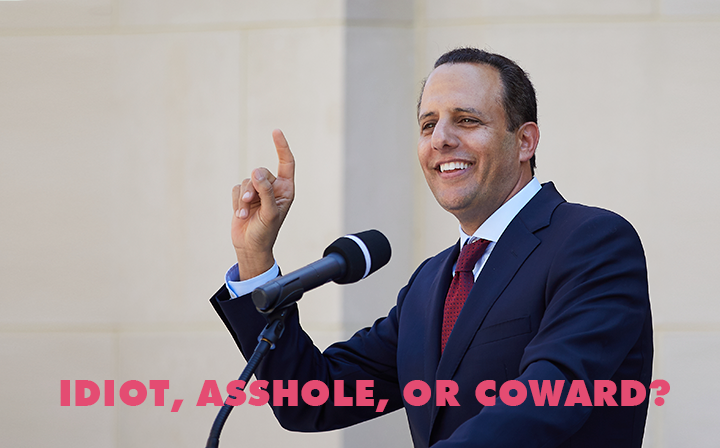

University of Oklahoma President Joseph Harroz, Jr. refuses to do the bare minimum for public health in regard to COVID-19

Professor Olberding writes:

Our stories do not yield fully masked classes. In a small classroom stuffed with 40 or 50 students, just a handful will wear a mask. Classes packing in hundreds may have fewer than half masked. Some faculty post online about their successes in getting students to wear masks. I read these posts closely because I want to know if there is some magic key, a particular appeal or strategy that could reliably work. I am a moral philosopher by trade, so I am also natively interested in how to morally motivate people to do what they’d rather not. So far, I have not uncovered any secrets…

We offer up our vulnerable loved ones, our bereavements, or our own medical histories like sacrifices before fickle gods — gods who, it turns out, are mostly teenagers vested with powers divine by our administration. We beg teenagers to think of our babies, to feel for our dead, and please not to kill us. Some of them oblige. Some do not — an alarming number do not. The university’s response so far amounts to: Beg better.

You can read the whole essay here.

@ UIowa staff have been instructed by admin/HR to remove signs from their work spaces begging students to “please wear masks” and our faculty openly mocked to their faces for pleading for mercy and aid for the care of the lives of their loved ones:

@DrMeerdink

I taught 135 students today. The two rooms were packed with no open seats. Only about 40 students had masks. When I described why I am wearing a mask and having virtual office hours (1 year old at home, his grandpa doing chemo treatment), I got eye rolls and dramatic sighs.

Solidarity. I remain amazed at how often I hear of such reactions on our campus. I never thought myself especially optimistic about the nature of people, but I have been so completely shocked that I’m really losing the thread… no longer sure what people even are. I haven’t had the kinds of reaction you describe myself, but this week does mark the first time a student yelled disrespect at me in class.

thanks Amy so sorry you’re having to endure this, this is what I would expect of many students, and at this point in the history of higher ed no one should be surprised by the moral vacuum of our venal regents and their handpicked president and her crew, but really the more tragic part is the lack of solidarity among faculty who aren’t willing to strike for themselves, staff, or students, don’t ever want to hear from these folks again about how they are imparting/imbuing humanist democratic values to their students…

The private university where I work has both a vaccine mandate and an indoor mask mandate, so I’m not facing this directly in my workplace. But based on fruitless conversations with family members and others, I also find myself feeling “no longer sure what people even are,” or perhaps simply unsure how genuine human discourse is even possible.

“But based on fruitless conversations with family members and others, I also find myself feeling “no longer sure what people even are,” or perhaps simply unsure how genuine human discourse is even possible.”

for folks who make it to the other side of this there are these sorts real open questions about the kinds of reasoning (debating, etc) that the humanities depts have been selling, unfortunately this current crisis has shown that we likely don’t have the personnel in place to entertain them let alone address them with substantial changes in theory, pedagogy, and evaluation (grades, peer-review, advancement, etc).

We might explore our schools’ precise definitions of things like “in-person class” to see what strategies are available to us.

Here’s the class format I switched to, after seeing how many unmasked students were crammed into my poorly ventilated classrooms with me on the first day. As far as I can tell, this is consistent with university rules:

I am very sorry for my US colleagues that they have to teach under such dangerous circumstances. Coming from Europe, I have a question: Why does nobody call for a strike? Dangerous working conditions are a very good and salient reason for a strike, in my opinion. It would also make clear that this is an issue between the faculty and the administration who is responsible for the safety of its employees. But there might be things I do not know about the US context which make a strike (legally?) impossible. That is why I ask…

I second this excellent question.

And if strikes are out of the question for some reason, then full and associate professors in such hazardous environments might seriously consider unilaterally moving their classes online–not as a *strike* but as an *exercise of academic freedom*.

(See, e.g., “Protecting students and faculty during a pandemic,” Indiana Conference of the AAUP, https://www.inaaup.org)

Jonathan Surovell’s proposal, above, also seems worth considering–especially for junior faculty, lecturers, adjuncts, and graduate students. Department heads might explicitly grant these precarious workers permission to do so.

Others might chime in here, but the short answer, I’d guess, is job insecurity even for the tenured. In my state, we’re forbidden by law from unionizing or striking. We have a Faculty Senate, but they so far have been overly cautious and utterly impotent, asking for things like “stronger language” to “encourage” masking. The Senate, in short, seems more a symbolic body than one that can secure good outcomes for faculty or the institution.

My sense is that defiance here entails going it alone and doing so with great uncertainty of what sorts of consequences might follow and whether anyone will have your back if things go bad. E.g., some colleagues contacting me about the Chronicle piece have worried I’ll now be fired. I’d be ok with that, but lots of people wouldn’t.

Thank you for this reply, Amy, and for the excellent article you contributed to CHE.

I share your sense that even senior faculty fear losing their jobs if they speak up or act out. And the personal stakes are especially high in states like yours that forbid strikes. It is plausible that unilaterally moving one’s classes online will also subject one to disciplinary measures, despite what the largely irrelevant AAUP urges. Moreover, I agree that there is great uncertainty about the prospects for success, even if faculty were to defy administrators and/or state law.

However–at what point do we declare this a moral emergency that demands institutional or (in the case of striking in no-strike states) civil disobedience?

To be clear, I think you’re right to attempt to beg with students and to use moral suasion with them as you’ve done. And brainstorming on Daily Nous about the most promising begging-techniques is a very worthwhile undertaking. (I say that sincerely and hope to see creative suggestions below.)

So I hope I don’t derail the valuable conversation you and Justin have initiated here by what I say next. I simply want to register my view–and perhaps you agree?–that, at least by the second or third week of the semester, the time for begging students will have passed and the time for more defiant efforts will begin.

I’m sure you agree–and your article implies as much–that we are not just begging to save our lives. Rather, these administrative policies imperil the public health. Therefore, the administrative response to “beg better” is simply appalling!

As the semester ramps up, senior faculty, in my view, need to seriously consider following the lead of the 2018-2019 k-12 striking teachers who, in many cases, also defied no-strike laws. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2018–2019_education_workers%27_strikes_in_the_United_States) Surely senior faculty tend to have more financial and social privilege than, e.g., West Virginia k-12 teachers.

What *general* excuse, then, could such privileged senior faculty possibly have to convene potential super-spreader events in at-risk communities?

So, as we beg students to help minimize the disaster that university administrations (no doubt driven by state governments) set in motion, let us also organize senior faculty behind the scenes. A petition might be a useful low-stakes way to test the waters for support.

Public health conditions are spiraling out of control in the U.S. South. I fear that a moment of truth, demanding institutional and/or civil disobedience, will soon be upon us.

“I fear that a moment of truth, demanding unilateral disobedience, will soon arrive”

I’m afraid that moment/call has come and gone and the overwhelming answer from faculty is count us out…

Lecturer with no job security here. There are things I like about my job. But I have too much pride and/or self-respect to be forced to put my family and friends at risk so that my President can earn a salary in the mid six figures and brag about enrollment at fancy parties. I doubt the perks of the job are worth such a loss of autonomy and subjection to such blatant and humiliating exploitation. Maybe I’m being proud in a way that will come back to haunt me. If so, I’m not sure I can be otherwise.

Above, dmf makes a point about faculty’s unwillingness to strike. What I’m seeing is that the vast, vast majority of senior faculty aren’t even willing to sign a petition. Maybe this is because they’re exposed to much less risk than we grunts: they teach fewer classes and many of those are advanced seminars with fewer and more mature students who are more likely to wear masks. I’ve never begrudged them this but I would have thought it wouldn’t be too much to expect them to put their names on a petition on behalf of their more at-risk colleagues.

I want to echo and elaborate upon AnonymousLecturer’s comment.

As regular readers of Daily Nous won’t be surprised to learn, over the summer I mass-emailed 2,000 or so employees at my former workplace (the University of Alabama in Huntsville) about these matters, in an effort to attract signatories to a related petition. 135 eventually signed on, but more than a dozen additional junior colleagues reached out to support the effort (and, reasonably enough, to beg-off from publicly signing in order to avoid possible retaliation). Several of them conveyed to me not only their private health anxieties and their frustrations with callous upper-administration–but also their resentments towards apparently idle or uninterested senior faculty.

(For what it’s worth, many senior faculty at my former school, including especially my former department chair, Nicholaos Jones, did and are doing exemplary work to protect junior colleagues.)

So I again urge senior faculty to redouble their efforts and to take vigorous steps to protect not only the public health, but their junior colleagues as well. Passions are obviously running high, and many junior colleagues are attentively watching their mentors for signals about what they may or should do in these confusing times!

In Florida where I am, it is illegal for state employees to strike. So, faculty would almost certainly lose their jobs. This is what is called a “right to work” state, which is Orwellian language that restricts workers’ rights.

As Jonathan Surovell does (thanks!), I’d love the hear what people working in similar conditions are doing, especially anything that seems to have worked to get more masks.

I realize some might say we should just defy our administration, but I’m asking in part as a faculty member acutely aware that we have untenured and, especially, graduate students not in a good position for that – people who need/want to stay within the bounds of the restrictions because the menace to their employment of getting in trouble with administration is far greater.

For what it’s worth, here are strategies that seemed to make slight good differences:

And, yes, I realize how pathetic all of the above sounds. This is our worklife now. Any suggestions at all about how people with little power and great job vulnerability could tweak things to get more students masking would be very much appreciated.

Fwiw I’m trying three tactics in my 280 person lecture class — it’s different though bc at Kansas we do have a mask policy that is being imperfectly followed (but it’s still kinda nuts with no distancing, vaccine requirement, class size limits, on-line teaching, etc):

1. If you had a student or a few last year who were in the hospital, or some such, mention that and say you really “hate the idea of getting that email from a current student in this class”. I think that might motivate a few by personalizing the threat and making your altruistic concern concrete and believable.

2. Announce cases in class by email or at lecture (anonymous numbers) if you are allowed. This will make rising numbers more concrete for them.

3. A university health guy here helpfully suggested using funny memes if you can to nudge without coming off as a scold.

Best of luck!

Has anyone tried an in-class mask debate? I could imagine asking students to work in small groups to advance arguments for or against masks, parliamentary style, with the first two groups arguing first, the second two groups conferring then responding, etc. Seems like a natural way to discuss ethical issues that is topical. Could let them know which theories are being assumed that will be covered later, when they come up. Just getting people to think for themselves about it would help, I would think. (Admittedly speaking as someone working at a university with a vaccine and mask mandate.)

1) do you really want to both-sides public health findings around protection from masks and vaccines cuz those are the issues in play?

2) is there any evidence in these cases that debate will be helpful in bringing people closer to understanding and adopting the relevant measures to adapt to the realties of our dire situation?

3) do you really want to leave the good of the commons up to individuals who are enrolled in learning how to think for themselves? Not to mention that the argument that my and others’ health should depend on individuals choosing/thinking for themselves is the reasoning offered by the BigLying politicians and their faithful administrators who are denying us basic public health measures of protection.

You raise good concerns, but I do think there are some reasons for both sides, that some of those reasons are bad ones, and that people are more likely to see that if they go through the process themselves. This is a highly politicized issue in which professors are assumed to be on the other side, which makes it different from many other issues. I think it would be better if this wasn’t left up to classroom debate, but I am assuming a case where we are looking for a rhetorical strategy because nothing else is left. I have found that discussing classroom policies in a way that gets students to think for themselves has been helpful in the past (e.g. on phone use in class).

I coach the university debate team and did just that to open the semester. Unfortunately, the participating students, despite usually being excellent, became bogged down in a definitional squabble and delivered a poor debate. It was a missed opportunity tbh.

On Twitter, there are a number of professors who report that students are shocked when the professors show current infection data. It seems like students think there is not that much covid around; maybe because universities are trying to minimize everything. So showing maps of your county covid infections from June juxtaposed with maps from August might help?

didn’t help Justice Breyer make his case against evictions:

https://twitter.com/SCOTUSblog/status/1431070502047584260

I’m replying pseudonymously here, since I don’t think I’m allowed to do these things at my university, but:

1) I told students that some of their peers had already emailed the first week saying that they can’t attend class because they have COVID, are quarantining because they had close exposure to someone with COVID, or are going home to attend the funeral of a relative who died of COVID. And I did actually get all those emails this week.

2) I made a pitch for mask wearing playing more to their self-interest than to any sympathy they might feel for my situation (unvaccinated infant at home). I said that if they wanted something resembling a normal semester with mostly in-person classes and social events, they really needed to be COVID conscious RIGHT NOW and get the university through this Delta variant spike.

3) For some reason we’re not supposed to make use of all those OWL cameras the school installed at great expense just last year, but I’m basically doing hybrid teaching without it being called hybrid. I told my students that all classes will be live-streamed on Zoom, and I don’t care if they attend in-person or via Zoom. I had about 25% of those enrolled in my classes on Zoom the first week, which makes for a pretty full classroom still, but at least they’re not packed in like sardines. I’m optimistic that natural student apathy will kick in and that Zoom percentage will go up as the semester progresses.

I teach at a state university in a state run by insane Republicans. The university is forbidden by law to mandate Covid vaccines for employees or students. However, there is an indoor mask mandate at my university. My classes, despite being too crowded for my liking, have 100 percent mask compliance. Only one student forgot their mask, and promptly took the one I offered to her. This is true, despite the fact that I have already received several raving conspiracy-laden homework assignments, suggesting that some students would definitely *not* wear a mask, if given the option.

University-imposed requirements backed up by the possibility of expulsion from class and disciplinary hearings work. Those of you who don’t have this kind of support from your administration, I am so sorry.

I’m wondering what are people’s experiences at colleges with mask mandates and such? What’s it like enforcing them in class? How much if any pushback do you get? My dean and department head scheduled me for all online and Zoom classes this semester since my wife and I have a couple of newborns at home (never say all admin is bad!) and I’m infinitely grateful. But even if I didn’t have newborns to worry about I wouldn’t want to teach in person as I’d absolutely dread going in to in person classes and having to enforce my CC’s mask mandate. I’ve had the shot so I’m not really worried about COVID harming me personally, but we have a lot of older students who might be vulnerable even with a shot and lots of my students always have kids under 12 so masks would be imperative. I’d have zero moral problem throwing students who didn’t comply out of the class or dropping them entirely if they were repeat offenders but I find those sorts of confrontations incredibly draining and they’re massively disruptive. So is it is bad as I think it would be even at schools in blue states? If you have mask mandates and similar measures how much does your school back you up on this? How much of enforcing it is left to you? I’m going to guess that it’s still bad, though not as bad as in deep red states, but here’s hoping I’m wrong.

Teaching at a private Catholic college in the Northeast, I didn’t find any difficulty enforcing the mask rules during the in-person portion of my hybrid classes last year. Students all had masks, and I only had to remind a couple of folks to pull the mask up over their nose. Overall our students are pretty deferential to authority (at least in the classroom), but I guess I’ll find out next week if attitudes toward masking have changed.

I’m at a state school in a red state. We have an indoor mask mandate and the university has said faculty can institute their own mask mandates, in case the university policy changes. Since we’re not collecting data on vaccination rates, I expect to be in masks for the semester – and I have told my students so.

Compliance has been imperfect, but solid. Like Derek Bowman, I sometimes I have to remind them to pull the mask over the nose or not to take it off during group work. They sometimes forget to put them on as the come in the building. I do plan to start bringing some to class because colleagues have seen students’ masks break in class, which seems like a potential issue. But no one’s come to class without a mask or acting like the don’t have to mask since the first day.

I think some of this is probably down to the optimism of the fall semester.

I really thought universities in US would adopt appropriate measures much more than they did so far. Still, with delta the landscape changed. Unless it’s tight fitting N95/KN95 you might just as well have nothing (badly fitting cloth or surgical masks won’t do much anything). Heavy Hepa filtration or even better open windows. All that is however simply to slow the spread to relieve the hospitals – children/teenagers/young people will get it in schools this fall – it’s fantasy to think otherwise (delta can’t be stopped in the way the older strains could). I think universities should require older and immunocompromised people to do online, independently of vax status, until Covid becomes endemic similarly to the flu and vaccines improve. They should be criminally accountable otherwise.

“Unless it’s tight fitting N95/KN95 you might just as well have nothing.”

What’s your evidence for this claim? I did a bit of Googling and I can’t find any research or expert opinions to this effect. The research I’m seeing indicates that cloth and surgical masks can make a big difference:

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.20.21262389v1

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.04.21261576v1

https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.09.21260257v1

I’m also seeing a lot of interviews with experts who assert unequivocally that, in the current context, masking is a must. A representative example is Stuart Cohen, Chief of the UC Davis Health Division of Infectious Diseases, who says, in response to the question, “Given the severity of the Delta variant, what sort of masks should we be wearing?”:

“Unless you are going to be in very intense circumstances, wearing a surgical mask should be more than adequate, or wearing a good cloth mask that fits well, particularly cloth masks that actually have filters on the inside of them.”

https://health.ucdavis.edu/health-news/newsroom/when-should-you-wear-a-mask-to-protect-against-the-delta-variant-video/2021/07

That being said, N95s and KN95s are obviously more effective than cloth or surgical masks. For those who want to use an N95 or KN95, but are concerned about the environmental impact of regularly using disposables, there’s a reusable one that looks promising:

https://castlegrade.com/products/g-series-mask

One course, the key with N95s is to completely seal off your face. Some N95s might work better for some faces than others, so one might need to experiment with different masks and practice sealing them.

For example, see https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.30.2100636

Most studies about masks effectiveness are preDelta. With delta you need tight fit not just filter. To expect children to have tightly fitted masks on the whole day is unrealistic. They take it off for lunch and that’s it, if it didnt fall off 10 times before. Delta spreads within seconds. To expect 300 students on your lecture hall to do so.. I have seen way to many cases of “taking it off to speak” to have any trust in this. It’s just not a realistic expectation.

The studies I cited aren’t pre-Delta–they’re specifically about the Delta variant.

I saw the Finnish study you link to. What it shows is that there was an outbreak in a context with widespread mask use. A case study like that doesn’t get us very close to the general claim that cloth and surgical masks don’t reduce the spread of the Delta variant.

Studies that would show that general claim would do little to show that the use of cloth masks in real life schools with children ages 6-12, with 24 children packed in one room with a teacher would do much. 3000 infections, confirmed, in schools in the first week in LA county, with full measures on. No ody says it won’t slow the spread a bit. But to think it will prevent older people or people at risk from getting infected in classrooms is to me still a pure academic abstraction.

The topic of conversation, though, is college. And by all accounts compliance with college mask mandates is high. The reduction in the spread of covid that this would produce would likely save lives, as it buys people more time to get vaccinated at a time when daily vaccinations are increasing again. For the same reason, it would save people from long-haul covid and long-term organ damage. It would also, as you acknowledge, reduce strain on hospitals.

I don’t disagree, I think. But it’s important to see what reduction means. If you are in a classroom where there is spread of aerosol infection, the classroom will be hit unevenly. So you are at different risk depending on where you sit, next to whom, how the air circulated and accumulated and so on (also it lingers a long time). Part of the classroom might have nothing, another a lot. With cloth mask you may achieve say 30 percent reduction. Great. But that is not prevention – instead of 10, only 7 will get it, for example. You won’t stop the spread, just slow it down. If you are older or immunocompromised person, you just shouldn’t really be there at this very high transmission stage of delta.

https://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/5.0061219

Yup, I agree with your qualitative conclusions.

Fascinating. What a bizarre situation.

If I were teaching at one of these schools, and prohibited from even offering incentives to students wearing masks, I’d be inclined to try something like this. I’d be keen to hear from others how it might be improved.

First, I’d send a message to all the students welcoming them to the course and indicating that, since some students are particularly vulnerable to the virus and that I, too, have vulnerable people at home, or whatever, I can only reasonably guarantee the safety of myself and the other students in the course if everyone wears a mask. I’d say that, if everyone is wearing a proper mask when I show up, class will go ahead as normal. But if some people choose not to wear a mask, I’d explain, I’ll have to arrange things differently for my own protection and the protection of others.

Then, I’d go to the classroom and see whether everyone is properly masked. If not, I’d say, “As I explained, because of serious safety concerns, I can’t teach the course *in this classroom* if not everyone is wearing a mask. Since some people aren’t, we’ll have to hold class outside today.” Then I’d walk everyone out to a space I had previously scouted out. This outdoor place would probably be far inferior, with noisy distractions at times and of course nowhere to write or project anything (I’d tell them not to worry — I’ll put everything they need up on the course site, including a video of the lectures).

If any students tried to move in too close to listen to me over the roar of whatever, I’d tell them that I’m sorry, but my own health doesn’t allow me to get that close.

After class, I’d send out another message, saying that I’m willing to try having the next class back in the scheduled classroom, but that straightforward concerns over my own health and that of others mean that that’s only possible if people happen to choose to wear their masks this time — and I’d stress that it’s technically their right to do so. If anyone fails to wear a mask, I’d do the same thing over again.

If anyone complains about these other students, I’d explain that university regulations forbid me from urging those students to wear masks or get vaccinated, or even from giving them an incentive for doing so. But I’d point out (if it’s true) that those rules don’t prevent the students from talking to the maskless students about it.

If anyone says that this whole thing is ridiculous and that they can’t hear what’s going on over the roar of traffic, and that they paid for a course to be taught in room such-and-such, I’d say that I empathize with their frustration, but that the rules are beyond my control and that teaching outdoors is the only way I can do my job without putting myself and others at lethal risk. I’d stress that only the higher administration at the university, and the governor’s office, can do anything about it, and invite the students to take the issue up with them if they’re not happy with it. I’d apologize that all this is necessary.

If the weather gets worse and worse and I eventually had to teach outside in a blizzard or tropical storm, it would probably help things along. The local news crew might receive an anonymous tip in advance, since that would be a great ‘visual’ for a story. But I suspect that, by that point, the students would either bring the maskless people in line or else just give up on trying to make class meetings work and watch the lectures on our course site. Then the entire course would move online due to the students’ decisions, not my own (my only action would be to take simple steps to safeguard my own health.

Through all this, I’d merely be looking after my own right to life (by moving things to a safe location), and not preventing any others from exercising their own state-given rights. The maskless students may stay in the classroom for as long as they wish, masked or unmasked. The students who sign up for courses get to take those courses, though the combination of bad governors, administrators and classmates might make the means of their doing so less favorable. I would not urge anyone who doesn’t want to wear a mask to wear one (though perhaps the other students would step up and do so). And I would not have to beg for mercy from these monstrous students: I would just let them choose between a reasonable outcome and an idiotic one.

To explain, in case it wasn’t clear:

– The approach would allow faculty to teach their courses without subjecting themselves to risk of infection;

– It would not involve begging;

– It would not involve requiring or even urging any students to wear masks; and

– It would not seem to violate these rules (especially since there seems to be a general understanding that instructors can teach courses outdoors at times at their discretion).

One can imagine that a state governor might try to push through a new law saying that university instructors may not teach outdoors. But really, I’d like to see them try that. Their whole case for not requiring people to wear masks or get vaccinated depends on our right to autonomy over our own bodies and health choices. All right — now some faculty members want to teach their courses outside because of concern for their own health. Those faculty members aren’t interfering with anyone else’s right to his or her own health decisions. Moreover, I think it would be hard to dispute that being in a room in which people might be maskless and unvaccinated is a health risk: that would amount to denying that the virus is airborne and infectious. But even if some governor tried to pull that off, it would come down to one person’s claim to bodily autonomy over another’s. If the government can require you to put your health at risk (according to your considered medical beliefs) in order to go to work, then by that same logic the government could compel people to get vaccinated in order to go to work. I can’t imagine that any of the anti-vaccination, anti-mask people would want that.

I agree with Justin that this plan is worth seriously considering. It could also be combined with Jonathan Surovell’s proposal, above.

You might also consider an outdoor teaching plan if, like me, you think indoor teaching may be hazardous even with full mask compliance. (Say, if the masks are low-quality and ill-fitting, if most students and community members are unvaccinated, if community covid rates are extremely high, if regional ICUs are at capacity, etc.)

And for precedent, philosophers can point to the Peripatetics and the Stoics!

Good to e-meet you again, Jeremy, and good on you for taking a bold stand on this. Someone with guts had to get it started.

And yes, referring to the Peripatetics and Stoics is a great idea for keeping the thing light. If these people carelessly promote tragedy, it can surprise them if one makes it a clever occasion for satire. It also helps keep one’s chin up, which is so important under fire. And since none of it seems to openly defy the rules, it might appeal to the many people who share your concerns but lack your courage.

I wonder whether teaching outside, in a blizzard, would galvanize public support in quite the way you seem to assume. Assuming that this is happening in a place without mask mandates, which interpretation is likelier to circulate along with your “great visual”: an interpretation according to which classes have to be held outside, even during a blizzard, because shortsighted officials refuse to implement a mask mandate, OR an interpretation according to which a self-righteous professor forces his students to have class outside, during a blizzard, because a single student refused to wear their mask? Perhaps stereotypes about professors work differently where you are. But around here, I wouldn’t bet that the popular interpretation would support your position!

Perhaps you’re right, but I think a great deal of it comes in the way it’s presented.

If the professor says, “Teaching in a blizzard is my way of protesting against the backward legislators and university administrators who have put in place these heartless policies,” I agree that some people would characterize it as self-righteous.

But if the professor says “I would love to go back to teaching in the classroom, but doing so would put my health at serious risk. Believe me, I would love to go back inside as much as anyone else. I’m freezing out here. But until my employer can provide me with a work environment that doesn’t expose me to a serious and possibly fatal illness, I’m not taking that risk, and it would be unreasonable for anyone to expect me to do so”, then I think it would be harder to make a ‘self-righteous’ label stick.

In such circumstances, one might also consider simply cancelling classes for the day. Again, as before: blame the policies and appeal to private and public health considerations.

Just because it’s perilous indoors doesn’t mean it’s any better outside!

Many people have noted that they are frightened of COVID despite being vaccinated because they have infants at home who cannot be vaccinated. It is worth noting that COVID is far less dangerous for infants than RSV: https://twitter.com/apsmunro/status/1430556935313666059

I have never heard any colleaugues with infants express similar fear about the risk of transmitting RSV to their infants. This suggests that either in the past people were far less frightened than they should have been about RSV’s danger to their infants or right now people are far more frightened than they should be about COVID’s danger to their infants.

I’m pretty sure that the guy whose Twitter you are linking is claiming that the rates or affect of RSV are unusually high and that this is somehow linked to COVID. His point seems to be that we might expect many diseases to be potentially more problematic in the current environment. Supposing he’s right (I have no clue), then people’s slight fear of RSV in the past could be an entirely correct response to the correspondingly lower risk in the past. And their current fear may reflect not only a concern for COVID but conditions that may be, for various reasons, harder to manage in the current environment. Is your point just that people should expand their sphere of concern? Because I think a lot have.

That is not correct. As he says in the following tweet, these RSV numbers are normal for the winter. What is unusual is the timing, which he attributes apparently to the lockdown and other social-distancing measures.

Yes, I saw that tweet too, but my understanding was that winter numbers are higher than the fall and hence the RSV numbers right now are anomalously high. Nicolas, who thinks your absolutely right, says below that Munro is worried about a “current surge of RSV” driven by COVID related factors.

So I guess I’m still just confused (though *actually* interested, for whatever that’s supposed to be worth). I get the point that RSV is supposed to be more dangerous than COVID for kids. I don’t seem to understand whether RSV is in a surge (that should be further covered in the media) or whether it’s just a matter of unusual timing.

Yes, the surge is a matter of timing, as I understand it. It’s catching up, if you will. But the fact that there’s a surge now is straining pediatric units. That’s the concern and not one we hear a lot about in the media. There’s also some (not fully clear but suggestive) evidence that RSV cases are actually driving part of rise in COVID pediatric hospitalizations — basically, many kids get admitted for (actually) RSV but test positive for COVID so it counts as a “for COVID” hospitalization. Don’t throw stones at me, I don’t know where and to what extent that’s true but that is certainly a possible confound.

That is indeed incorrect. I’ve been following Munro for a while and the consistent message I’m getting from the data he and others share is that RSV and other respiratory viruses, including influenza, have been more dangerous for kids since before the pandemic and are likely to remain so. The current surge of RSV is also very concerning, despite the near total absence of coverage in the press, and from what people in the know suggest it’s more due to the pandemic *response* (including untrained immune systems as a result of isolation) than to SARS-CoV-2.

*Maybe* people should “expand their sphere of concern” and start worrying about the general fact that kids get sick at daycare and school, which is how they build up their immune system. Maybe colds and flu are worse than we previously assumed. Maybe we should teach masked forever because of RSV. But if that’s the view, it should be debated as such, not as the fanciful, unfounded assumption that COVID-19 is an unprecedented threat to pediatric health. Chris is absolutely right, and Munro is worth following. He’s one of the saner voices, and a measured, reassuring, and extremely well informed voice in the current environment.

Here’s the best evidence summary we have, if you’re actually interested:

https://dontforgetthebubbles.com/evidence-summary-paediatric-covid-19-literature/

(I wouldn’t think keeping kids in masks forever has any chance of happening, though, personally, I think schools would be wise to implement mask policies during periods when infections are especially high and hospitals are overwhelmed in the community.)

Also, why do you say that going to indoors classrooms, in the style of 20th century public education, is how children build up their immune systems? Wouldn’t playing outdoors, in mud and dirt, with animals and other kids, etc., help a child develop their immune system? (I certainly agree that excessive isolation or staying inside one’s home too much have all kinds of negative health effects.)

I was more interested in RSV than flu, but since you’re asking, it depends on what we mean by risk and which age groups we’re talking about. One thing that’s unsure though, is whether it makes sense to compare outcomes for COVID and flu in a given season. When we thought COVID was going away, it was clear that the flu was worse since it is endemic and it changes every year. But now that COVID is on track to become endemic, it’s unclear how the risk profile is going to change. To be frank, I have no idea and I’m (un)happy to concede that COVID might become as bad as the flu. But again, we don’t shut down schools for months during the flu season. Maybe we should, is what some people seem to be implying. Even then, if we look at deaths, the range is much wider for COVID, and the lower bound much lower, than for the flu. See e.g. this chart. Now, if you look at RSV you’ll see the difference quite clearly, both for hospitalizations and deaths.

Re numbers, I frankly wouldn’t go too fast claiming that over any given full year COVID will indefinitely continue infecting more kids than the flu. It may, it may not, I’d bet it won’t but I could be wrong. Remember we’ve had surprisingly low flu case numbers last year (maybe in large part because of “viral interference”; no, it’s not masks and social distancing), so comparing numbers over the last twelve months doesn’t tell us much. It’s also likely (but again, I don’t know) that COVID will not simply add its own caseload to the regular caseload of influenza, for a bunch of apparently complex reasons. It may, it may not, we don’t know.

Long COVID: this is a fraught topic that I’d rather not get into here but there you go. Studies so far either lacked a control group or didn’t find a significant difference in long-term symptoms between in children who tested positive for antibodies and those in the control group. I don’t have the sources with me right now but it’s not hard to find solid debunking discussions of the scary articles you can read in the NYT, WaPo and Atlantic. Long term effects of respiratory viruses are a well-known issue and we don’t have substantial evidence that COVID is worse than other viruses for children. It may be, I just haven’t seen any compelling evidence yet. This is not to say that long term effects are not to be taken seriously, but we are getting back to the original question: are we no longer willing to accept a baseline level of risk that we were previously willing to accept? If not, why and at what cost?

Finally, sure there are many concurrent ways kids build up their immune system but I’m not sure you really want to deny that contracting coronaviruses when young isn’t one of them. I did not claim that “20th century public education” was absolutely necessary for immunity but I thought it was also good for other reasons. 2021, the year we started having to argue that school was good for kids.

Here’s a good summary of a recent study on long term symptoms:

https://theconversation.com/covid-long-lasting-symptoms-rarer-in-children-than-in-adults-new-research-165701

Well, of course I didn’t deny that school or daycare is, by and large, “good for kids” (that’s an oversimplification, but too far afield to go into). I was asking about your claim, as I understood it, that school is important for immune development.

On long-term effects, I’m not surprised to learn that children are less susceptible than adults. But the data it provides is in line with what I was saying: a non-negligible number of children who get covide–more than with the comparison viruses–develop long-haul covid. And the long term damage this causes isn’t well understood. We don’t yet know how often the virus stays in the body or for how long. I agree, the issue is fraught and there’s a lot we don’t understand.

I agree about not making claims about how covid will indefinitely continue. I’m just talking about the actual situation, where many hospitals’ pediatric wings are getting big influxes of covid patients. I don’t think the flu tends to do this, but correct me if I’m wrong.

Lastly, I don’t think comparisons with the flu are essential to any policy or personal decision. But I think it’s important to be careful with them, as playing up the similiarities can distort risk calculations. That’s why I questioned your claim that “RSV and other respiratory viruses, including influenza, have been more dangerous for kids since before the pandemic and are likely to remain so.”

(The table you shared gives a single estimate for children’s flu death rate. The author says ths is based on CDC estimates of the *symptomatic* flu infections. But apparently about 1/3 of flu symptoms are asymptomatic. Also, the CDC gives a range of estimates for symptomatic infections. So it’s not clear to me why the author of the table doesn’t give a range of corresponding death rates. If they were to do this, I wonder if the data would come more into line with the study I referenced earlier, which found no significant difference in the rate of hospitalization, ICU, or ventilation admission. Comparison between this author’s two rates is at least problematic. Again, it may be that the flu has a higher IFR for children. But it’s clear that covid’s disease burden is much heavier, at present, given its higher transmissibility.)

Thanks for engaging, Jonathan. I’m not really interested in litigating the flu vs Covid debate. The numbers are low in both cases and there are good reasons to think the flu will remain a bigger concern forever.

Right now, maybe. But flu infection rates are 20-30% every year in children. And that’s with a flu vaccine.

But really not much hangs on this. Again, RSV is the bigger concern here, and again, if it was not a big concern pre Covid it’s not clear why Covid should be a bigger concern.

On long haul I’m not going to convince you. As you say there’s a lot we don’t understand, and this cuts both ways.

It’s really important to emphasize that the numbers we’re talking about are extremely low:

https://twitter.com/jcbarret/status/1432413287304548354?s=20

Are you sure you’re not interested in litigating this? 🙂

Anyway, it seems plausible that once covid vaccines become available to children the virus will soon become less of a threat to them than the flu. I would just emphasize, though, that the original topic was teachers’ concerns about giving their kids (or, more specifically, infants) covid *this semester.*

Estimates of the proportion of children who get long-haul covid vary wildly, from 1/50 to 1/3. That’s high for that kind of thing, high enough for teachers to adjust their classroom formats. Different people have different risk tolerances. I’d do a heck of a lot to avoid, say, a 5% chance my kid gets long-haul covid. But as with many aspects of parenting, what I’ll do and what I’m able to do depend on my circumstances. It’s not a one-size-fits-all thing.

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01935-7

The flu thing, no. I’ve said what I had to say. I think it’s orthogonal to the issue at hand. As for risk tolerance, sure parents’ choices are highly contextual. We don’t have the same estimates, and that’s fine. I have to go give my kids a bath, cook dinner, and get them ready for school tomorrow so I’ll leave it here. But thanks for a good convo.

Thank you. (And just fyi, I meant the offer to further litigate as a light-hearted joke.)

We don’t know the long-term implications of Covid, that’s true, but it’s not true that respiratory viruses (and this is not just respiratory virus anway) can’t have serious-long term effects. And I’m not talking about long Covid. The 1918 influenza epidemic has long been considered a possible culprit in the epidemic of Parkinsonism (encephalitis lethargica) discussed by Oliver Sacks in his wonderful Awakenings. My love of that book has influenced my reaction to Covid–not for myself, as I’m high risk anyway, but for my young adult children–from early on, and now I’m beginning to see discussion of the potential for a post pandemic syndrome, whether encephalitis lethargica or something else, in the medical commumunity. In fact, many cases of Parkinson’s may have a viral origin.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7347

The key thing for me is, this is a novel virus. We don’t know what it will do to the body long term. Not all viruses leave the body, and many viruses do terrible things years later, either because they are still present in the body or because of the damage they left behind. Hepatitis, HPV, Polio, Measles (which causes SSPE), chicken pox, etc. Viruses likely play an even larger role in the development of cancer than we now know. Viruses can have terrible effects on the developing fetus (and there is some sign already that hearing problems may arise in fetuses born to mothers infected with Covid). Why should we assume that such a devastating virus (I’ve read that it would have killed many more than the 1918 epidemic had we only the medical interventions available at that time–no antibiotics, no ventilators, no ECMO) has no long-term effects on the body? Caution requires us to tread carefully when a virus is as unknown, devastating, and unpredictable as this one. Even if only a small number of today’s children were to develop post-infection syndromes like encepalitis lethargica the cost in their lost life-years might dwarf the cost to us older folk, who have less of the good stuff left to lose.

Since I explicitly claimed that long term symptoms have long been a well known consequence of other respiratory viruses I’m not sure sure you’re replying to me. In any case I don’t know what follows from your sincere and understandable concern about viruses. Would you mind explaining what you think we should do to prevent those long term symptoms across all the viruses to which children and others are exposed? I have two young children and family members with cancer so I’m curious to hear what I should do and for how long.

I wish I had answers to that. Apparently with Delta we’ve missed the opportunity to beat it back, and the great majority of us will be infected at some point. Far better that it happen after vaccination, though, and I would hope we’d do what we can to prevent children from being infected en masse on what is essentially a hope and a prayer that everything will be okay. That includes masking, vaccine requirements for providers (obviously!), testing and tracing, and yes, giving work accommodations to parents of young children. It seems that a number of university administrations (not mine, thankfully) have decided to let the virus rip through an unmasked student body, all but guaranteeing breakthrough infections for faculty who have susceptible children. A number of comments in this thread (apologies–I should have directed my reply to the first comment in the thread) suggest parents shouldn’t worry. I think they have good reason to worry and should be supported in any attempts to seek accommodation. It’s fine to reassure people if what you want to do is make them feel better, but it’s another thing altogether to minimize their their rational concerns, and in such a way that (replicated and amplified over social media) it becomes socially and politically more difficult for them to seek redress.

I agree with and respect the general sentiment. I don’t think Chris was minimizing parents’ concerns, and I am not. I have my own concerns about kids, especially from underserved populations (the immense costs to them of the pandemic response), which have been aggressively dismissed by the majority of people I’ve interacted with on the topic, including colleagues and other philosophers who should know better. I think Chris and I were trying to reassure parents, speaking, at least for me, as a parent who’s spent many more hours than I should reading about this from pediatricians and public health experts with a reputable track record over the pandemic.

Given how disproportionately represented the concern about long covid in children has been in our shared environment, relative to the kinds of concerns I have, I’m not really worried that what’s going to be replicated and amplified is any sort of minimization of the sort of concerns you raise. If anything, we have ample evidence that social media spreads fear and panic more than reassurance.

Copied the link wrong!

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7347327/

“But if that’s the view, it should be debated as such, not as the fanciful, unfounded assumption that COVID-19 is an unprecedented threat to pediatric health.”

COVID-19 *is* an unprecedented threat to pediatric health, just as it is an unprecedented threat to everyone’s health. Here I’m using “unprecedented” to mean that this particular type of threat does not have a precedent.

Should I understand your claim differently? Are you saying that it is “fanciful” and “unfounded” to assume, not that the *type* of threat is unprecedented, but that the *magnitude* of the threat is unprecedented?

Yea, Molly, magnitude. You know what I mean. The sentence occurs in the middle of a discussion that makes that very clear. It’s not an analytic philosophy paper so I don’t know why you’re trying to pick words apart.

If one is looking for a strategy that might work and perhaps won’t cause students to spitefully decide to go unmasked because they are (understandably) tired of being lectured at about masks, perhaps this might work. Start by expressing gratitude.

Explain to your students that the pandemic has been something that is unfair. Explain that they reasonably might believe that they have been denied a lifestyle that they should have expected to have. For some of them, their high school graduation may have been canceled. Others have lost their jobs and might be struggling to pay for tuition or essentials (and still others may have been forced to delay enrolling because they could not save enough for college after the pandemic rendered them unemployed). Others may have been considered “essential workers” and been expected to work and put themselves at risk of contracting COVID. Some of them have been looking forward to starting college and enjoying what they were told should be an important time in their lives. Students might reasonably expect that they should be making lifelong friends, finding future wives and husbands, securing internships that will begin their lifelong careers, enjoying the amenities that universities use to differentiate themselves to attract students, and doing all the dumb things people say they did in college. Explain that students are receiving a compromised college experience, with worse teaching and mentorship than they should be receiving. And explain that this is unfair because 95% of COVID fatalities have been in those ages 45 and above. While college-aged students are at lower risk for hospitalization and death than nearly all other age groups, they have been asked to put their lives on pause or to accept an impoverished way of living for the sake of protecting the elderly and other particularly vulnerable groups. Others got the chance to fully begin adulthood, and to protect what those others have secured for themselves, college-aged students are being asked to not fully begin adulthood. And given the effectiveness of vaccines, those who currently suffer from severe illness and death from COVID are largely responsible for their own fates, which makes placing additional burdens on college-aged students additionally unfair.

And yet, college-aged Americans have to this point admirably endured this unfairness. Explain that it is understandable, and perhaps even appropriate, for them to try to return to normal life as the country transitions to treating COVID as endemic. But, as unfair as it is to ask more of a group that has already given much, you will ask more of them. Explain that if a student has a fever or other symptoms, here are the university resources to consult with, email all of one’s instructors, and do not go to class until one has a negative test. Explain that while the risk of severe illness and death is low for students of this age group, they are not zero. Even illness that doesn’t require hospitalization is unpleasant. No one in the class is likely to volunteer for a high fever, body aches, fatigue, nausea, and/or loss of taste and smell because such things are unpleasant. Explain that together, all of you as a class can try to protect one another from such unpleasantness. Explain that you do what you can to ensure that your classroom is a place where everyone has an opportunity to receive the education that he or she is paying for and thereby entitled to. Explain that you ask that students get vaccinated and wear masks to help you and their fellow classmates stay healthy because you cannot deliver the education they are paying for if you become ill and their fellow students cannot receive the educations they are paying for if they become ill.

Perhaps by recognizing the costs students have endured and are asked to continue to endure (instead of trying to minimize or dismiss those costs), one can prevent students from adopting a defensive position that encourages them to double down on not wearing masks or not being vaccinated.