Strange Philosophical Claims By Scientists

Did you know that the brain cortex has “an amount of free will exceeding 96 terabytes per second”? No? Is it because… umm… you thought it was some other number of terabytes?

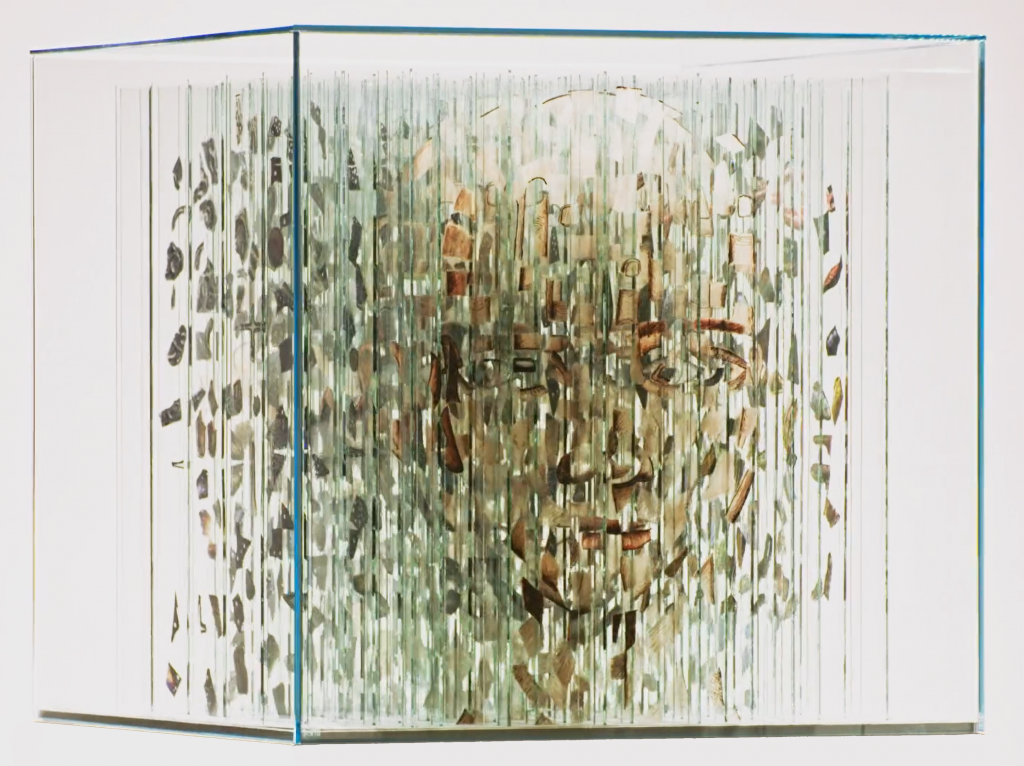

[“Head Instructor” by Thomas Medicus]

Inherent biases in the quantum propensities for alternative physical outcomes provide varying amounts of free will, which can be quantified with the expected information gain from learning the actual course of action chosen by the nervous system. For example, neuronal electric spikes evoke deterministic synaptic vesicle release in the synapses of sensory or somatomotor pathways, with no free will manifested. In cortical synapses, however, vesicle release is triggered indeterministically with probability of 0.35 per spike. This grants the brain cortex, with its over 100 trillion synapses, an amount of free will exceeding 96 terabytes per second.

Now perhaps free will can be measured in terabytes. I’m skeptical, but I don’t intend for this post to be an occasion for picking apart the argument and evidence for that.

Rather, Georgiev’s claim seemed like a good starting example for a collection of philosophical statements made by scientists that strike philosophers as bizarre. Please share other examples in the comments. Such a collection might not only be amusing, but informative, perhaps revealing common misunderstandings. Of course, the possibility for misunderstandings is a two way street, as some things said by scientists that sound strange to philosophers might nonetheless be true, and examples to that effect are welcome, as well.

(Thanks to Matt King for the tip.)

[More about “Head Instructor”]

Some related posts: Which Scientific Disciplines Cite Philosophy of Science?, Needed: A Philosophy Cheat Sheet for Scientists, When Scientists Read Philosophy, Are They Reading The “Wrong Philosophers”?

“Because there is a law such as gravity, the Universe can and will create itself from nothing.”

-Stephen Hawking

The weirdness in the paper looks like it’s more terminological than substantive: from what I can tell by “free will” the author just means the difference between the information we gain about what a system will do by observing what it actually does and the information about what it will do given it’s current state.

In scientific publication these days there’s a great deal of fakery going on. There are computer programs to produce fake papers, and many academicians, esp. in poorly (academically) policed countries generate papers that are not much better. This paper was deposited to a preprint “archive” service that simply uploads ANYTHING sent to it as a paper “in submission,” as the present paper is. To take a preprint seriously you have to check the author’s bona fides and/or follow the paper to publication. Preprint archives are a good idea that’s being abused. It’s not good for scientists to be represented by such papers and it’s annoying for scholars to have to wade through the fakes.

The article is published in academic journal “BioSystems” by Elsevier. Also it is indexed in MEDLINE and available from PubMed. Finally, the arXiv repository is moderated and it provides “free manuscript version” for those who do not have subscription to the paid journal. Not to mention, that the arXiv entry clearly indicates the Journal-Ref information. For other readers of the post, here is the complete bibliographic information with all relevant links:

Danko D. Georgiev. Quantum propensities in the brain cortex and free will. Biosystems 2021; 208: 104474.

http://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystems.2021.104474

http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34242745

http://arxiv.org/abs/2107.06572

I can’t believe the context of this article. Casting doubt seemingly because you don’t understand the content? The daring scientists are onto some real stuff with quantum consciousness. Fractal patterns and sacred geometry could lend someone lots of insight.

“Can we, in the identity 1 + 1 = 2, put for 1 in both places some one and the same object, say the Moon?” – Gottlob Frege

Also Frege: “[B]ut we can never–to take a crude example–decide by means of our definitions whether any concept has the number Julius Caesar belonging to it, or whether that same familiar conqueror of Gaul is a number or is not.”

What’s supposed to be bizarre? The definitions to which he refers don’t determine what counts as a number, and so don’t rule out the referent of ‘the number Julius Ceasar’ or the referent of ‘the conquerer of Gaul’.

Immediately afterward, Frege writes that it seems we cannot make the replacement. Does this statement actually strike philosophers as bizarre? I’m not sure why it would, for it seems obvious that the replacement makes for a transition from a simple mathematical truth (1 + 1 = 2) to nonsense (the Moon + the Moon = 2). What’s bizarre about it?

I think you’ve identified the bizarreness: “it seems obvious”. Why ask the question? Why would a mathematician find this interesting? It takes a special type to get puzzled about whether Julius Caesar is a number – and to want a definition to show that this isn’t so.

Frege is not puzzled about whether Caesar is a number. He wants mathematics to have a satisfactory answer to the question: what is the number 1? He uses the example of Ceasar to illustrate why it won’t suffice to reject the question on the basis of a similarity between variables and ‘1’. This is why he asks the question. And a mathematician would find it interesting to the extent that she is interested in ensuring that arithmetic has a foundation as solid as Euclidean geometry ‘s.

“What is the number 1?” – I think you’re digging Frege’s hole deeper!

Are you still under the impression that these things strike philosophers as bizarre? If you are, I’m beginning to wonder whether you’ve studied philosophy!

Cantor and von Neumann, to name two, offered explicit definitions of the number 1. Hilbert and Brouwer were concerned with closely related questions.

Is it sufficient to understand identity by just defining number 1? The “=“ sign can mean two things: identity or result. While the “+” sign can also, mean two things: summation or combination.

I fail to see how one can answer the original question without defining “+” and “=“ as well.

“What is the number 1 referring to?” would be a more accurate phrasing, given what I know of philosopher-talk. “a + a = 2” is basically the same as “moon + moon = 2,” except how are we sure that it does? Yet, science uses math as a referent for real-world events all the time.

I think the scientist’s attitude is more pragmatic, meaning they leave these questions open so often that it’s become habitual to do so, and they don’t necessarily see why it would be questioned.

I recall Frege’s point being more that his own proposed definition doesn’t solve the JC problem, and is thus deficient. (But it’s a long time since I’ve studied Grundlagen.)

That’s a fair assessment when considering the overall importance of the example for the Fregean project. But my view is that, in the context of the introduction to his Grundlagen (where the quoted passage occurs), it’s best to understand the example as providing support for a distinction between the use of variables (as in ‘a + a – a = a’) and the use of the numeral ‘1’ (as in ‘1 + 1 = 2’). The former “serves to express the generality of propositions.” The same cannot be said for the latter. His thought seems to be this: although it’s true that whatever number a may be, a true proposition results from substituting the appropriate numeral at every occurrence of ‘a’, it is not true that whatever thing 1 may be, a true proposition results from substituting the appropriate symbol for it at every occurrence of ‘1’.

FWIW, I probably studied his Grundlagen more recently than you did. But that, of course, doesn’t mean my interpretation is better than yours!

I’m talking about the Moon example, above. If you’re talking about the Caesar example, I agree with you: it is in response to a definition he proposes, and intended to show the deficiency of the proposal.

Just the preview for Neil deGrasse Tyson’s MasterClass contains multiple strange philosophical claims.

For instance, he says “I have come to realize that there are three categories of truth. Personal truth, political truth, and the objective truths that shape our understanding of the universe.”

He also says that the course will help you turn data into information and information into knowledge and knowledge into wisdom.

I suspect the entire class is chock full of strange philosophical claims.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=io6QdGcoWMU

I once came across an interesting article titled “A Psychiatric Dialogue on the Mind-Body Problem” published in The American Journal of Psychiatry. The teacher in the dialogue explains some of the major views and theories on the problem and at one point drops this gem:

“An alternative approach to this problem is offered by the theory of eliminative materialism or, as it is sometimes called, epiphenomenonalism”.

No, I didn’t spell that wrong either; that is how the author actually wrote it.

https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.989

Sounds to me like the scientist wasn’t thinking about what they’re writing, and instead meant “free will” in the context of “willpower” that is “free” to do things beyond basic bodily functions.

That or we’re giving medical degrees to clickbait journalists. Which is true in this day and age anyway.

Misunderstandings arise because a lot of science articles fail to define their abstract terms. A health science article does not necessarily need to define “cardiovascular system” since it’s understood by both specialists and educated non-specialists.

Even in the realm of theoretical physics, things can get very philosophical. This is because the theories rely a lot on *logical claims* (including mathematical ones) that have yet to be adequately tested or observed empirically.

Much of theory whether in science or philosophy relies on logical claims even if in reality, it has yet to be shown empirically true. People go into theory partly because logic allows them to explore possibilities even if empirically their theories are out of reach at the moment.

There is also the related category of technical statements that seem strange or at least fanciful when the specialist terminology involved is interpreted as ordinary language.

A personal favorite: between every two halos is another halo, which is a coherent (and true!) statement about the hyperreal numbers in nonstandard analysis.

It seems plausible to me that the claim in the original post is a statement of this kind, although I am not familiar enough with the field to say, and I haven’t had a chance to look at the paper.

May I suggest Section 3 of:

http://irafs.org/stoqatpul/lat/materials/basti_paper_cle_new2.pdf

Stephen Hawking was interviewed by Larry King on his primetime CNN show on Sept. 10, 2010. Here is a brief exchange from the interview ( https://transcripts.cnn.com/show/lkl/date/2010-09-10/segment/01)

“KING: You say that science can explain the universe without the need for a creator. But what is that explanation? Why is there something instead of nothing?”

HAWKING: Gravity and quantum theory cause universes to be created spontaneously out of nothing.

KING: You write that because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing. Will you tell me how that law came into existence?

HAWKING: Gravity is a consequence of “M” theory, which is the only possible unified theory. It’s like saying, why is two plus two four?”

I don’t know if Larry King misstated Hawking’s argument (although Hawking did not correct him) in attributing to him the claim that “the universe can and will create itself from nothing.” But it seems in flat contradiction to the principle *ex nihilo nihil fit*. Also, in describing M-theory as the only possible physical theory, is Hawking saying that the physical universe exists and has the properties it does by way of logical necessity? Is Hawking a Spinozist? Is this a widely shared view in physics? If Hawking is correct, does this mean that one is mistaken in thinking the universe could have been any other way than it actually is?

From Wikipedia

The expansion of the universe is the increase in distance between any two given gravitationally unbound parts of the observable universe with time.[1] It is an intrinsic expansion whereby the scale of space itself changes. The universe does not expand “into” anything and does not require space to exist “outside” it. Technically, neither space nor objects in space move. Instead it is the metric governing the size and geometry of spacetime itself that changes in scale. As the spatial part of the universe’s spacetime metric increases in scale, objects move apart from one another at ever-increasing speeds. To any observer in the universe, it appears that all of space is expanding while all but the nearest galaxies recede at speeds that are proportional to their distance from the observer – at great enough distances the speeds exceed even the speed of light.

“Science can determine human values.”

Sam Harris

(He later explained what he meant by this; but his original claim was rather confusing.)