OUP’s Prestige Monopoly (guest post)

Oxford University Press (OUP) has an excellent reputation in philosophy and publishes a lot of philosophy books. That seems like a good thing, but are there reasons to be concerned by the publisher’s disciplinary dominance?

Robert Pasnau, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Colorado, Boulder, thinks there might be, as he explains in the following guest post*. (A version of this post first appeared at Professor Pasnau’s blog, In medias PHIL.)

[Suzanne Duchamp, “Solitude-Funnel” (detail)]

OUP’s Prestige Monopoly

by Robert Pasnau

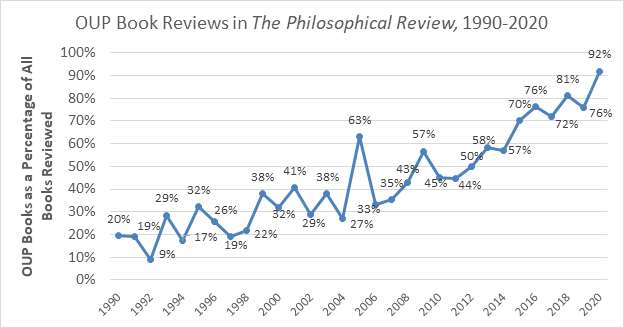

In reading through the 2020 volume of The Philosophical Review, I noticed a funny thing: every book they reviewed was published by Oxford University Press. Well, not every book but, to be exact, 23 out of 25. That’s not how I remember things being back when I was a student, so I went back and looked. In 1990, OUP was also the leading recipient of reviews in The Philosophical Review, but accounted for just 12 of the 61 reviews. Books from 21 other presses were also reviewed, and Blackwell and Cambridge were tied for runner-up, with 7 entries apiece.

I asked my own student, Colton Kunzeman, to go through the intervening years, and he produced this illuminating chart:

A quick look at some other philosophy journals that publish a significant number of book reviews turned up these numbers for 2020:

- Mind: 23 of 36 reviews (64%)

- Australasian Journal of Philosophy: 13 of 15 (87%)

- Analysis: 24 of 26 (92%)

- Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews: 70 of 167 (42%)

The NDPR rate is significantly lower, I think, because they review so many books. They can in effect review all of OUP’s philosophy monographs and still have room for a lot of other presses. As for Mind’s rate of 64%, if that seems comparatively unimpressive, bear in mind that the remaining 36% is split among all other presses. To put that in perspective, Mind in 2020 reviewed roughly 10 times more OUP books than books from any other publisher.

What’s going on here?

What these numbers suggest, and what anyone who’s paying attention will have noticed to some degree already, is the extent to which OUP is increasingly the dominant publisher in philosophy. It’s not the case, to be sure, that OUP dominates all parts of philosophy publishing. With regard to textbooks, guidebooks, and translations, they have lots of competition. But when it comes to scholarly monographs, OUP has secured for itself a near monopoly on the field: not a monopoly in terms of absolute numbers, since plenty of other presses are publishing monographs in philosophy, but a prestige monopoly.

Part of the reason for this, perhaps, is that there’s been a steadily smaller market for monographs in recent years, and as a result academic presses generally devote fewer resources to this than they used to. (On that subject my colleague at Norlin Library, Frederick Carey, recommends this article and this book, esp. ch. 5.) Still, obviously, there are plenty of presses that are publishing monographs in philosophy, and the reality seems to be that OUP is just outcompeting them, at least in this segment of the market. I asked Peter Momtchiloff, the OUP-UK editor for philosophy, if he was willing to comment on this situation, and he responded:

I think we have worked hard on philosophy publishing for a long time, aiming to cover all the areas that are typically covered in research-oriented philosophy departments, and responding to what philosophers think is good rather than trying to impose external ideas of what philosophy research publishing should be like. Apologies if this sounds boastful or ingratiating.

To me that sounds excessively modest. For decades now, Peter has worked like no other editor in the field to cultivate relationships with both young and established scholars. He makes people feel as if OUP really wants their books, and over time these relationships have paid off. (Peter Ohlin, the OUP-US editor, has a similarly longstanding presence in the field and receives rave reviews from those who work with him.)

Yet although this story is in part one of triumph for OUP, it also should leave philosophers feeling a certain amount of concern. Even if OUP’s monopoly is benevolent and well-earned, we should ask ourselves whether it is in the interests of the field. One way in which it would not be is if OUP were doing an inferior job editing and publishing its books. To gauge this situation, I reached out to 10 senior scholars in the field who recently published books with OUP and asked them for their impressions. All were kind enough to reply, and most were wholly enthusiastic. Typical responses were “wonderful experience,” “really excellent,” “always been really happy,” “extraordinary positive,” “uniformly good experiences.” So this perhaps can be added to the story of why OUP has become so dominant: that they do very good work publishing books. And to this it might be added that their books are reasonably priced and generally available in paperback.

To the extent that the scholars surveyed had reservations, those concerned the process of copy editing, proofreading, and typesetting. One scholar spoke of the “train wreck” of the typeset page proofs that had to be straightened out over a “bazillion hours.” I myself have noticed that OUP books are not always edited as carefully as one would like. In one short but prominent recent OUP book, I managed to find—simply by reading through the book in the usual way—51 typos, as well as countless stylistic infelicities of the sort that any decent copy editor ought to have fixed. I asked Peter Momtchiloff whether there might have been some decline in OUP’s production standards, and he passed this query on to the production department and got the response one would hope for, that “our quality standards haven’t changed.”

Be that as it may, the production process has certainly changed. A decade ago, books went through a multi-stage production process: copy editing, which was then reviewed by the author, followed by typesetting, which was then proofread by the author and the press. Of late, however, those stages have been compressed into one. Books are copy edited and typeset and then sent to the author, who is expected at that point to cope with any difficulties that have arisen in either the copy editing or the typesetting stage. The scholar quoted in the previous paragraph blamed the “train wreck” on this compression of stages. As for proof reading, that same scholar was frankly perplexed by the question, having seen no sign of any proofreading. This, too, was how the other author responded when I forwarded my list of 51 typos: not by blaming OUP for the mess, but with self-blame for being terrible at proofreading.

With these thoughts in mind, last month I asked the production manager of the latest volume of Oxford Studies in Medieval Philosophy whether this book would be proofread. Writing from India, he replied: “We do have the service for proofreading and I can check with editorial for the possibility on this if you prefer to hire one…. Kindly note inclusion of this new service could have an impact on the overall schedule and incurs additional cost for proofreading.” When I expressed surprise to him that OUP itself wouldn’t proofread the book, he replied, “We do the in-house proofread by default for all OUP books at our end.” Now, I’ve had generally excellent experiences with the people to whom OUP outsources their production, and with this production manager in particular. Even so, this exchange left me not altogether confident in the ongoing rigor of OUP’s quality standards.

I asked Peter M. a few more questions. He told me that the OUP philosophy editors publish around 200 academic books a year, split fairly evenly between the UK and US offices. He said they do not keep statistics on acceptance rates, but that “most unsolicited proposals are rejected.” (It would be interesting to know more about this, since, notoriously, acceptance rates at the top journals in the field are now under 5%.) To a query about whether it might be desirable to evaluate submissions blind (as do most good journals), he replied that while, like other publishers, they do not judge submissions anonymously, still “decisions about publication are based on expert review of material submitted, not on the author’s standing or track record.” (Perhaps one should add that with a monograph, unlike with a single paper, it’s not likely that an expert in the field would be unable to discern the author’s identity.)

One recent very positive development at OUP is an upgrade at Oxford Scholarship Online. In the past, as I’ve bitterly complained, Oxford books have been available online only in a fairly wretched reformatted version, unpleasant to read and full of errors. Those bad old versions are still there, but new books, at long last, are appearing in OSO as glorious digital images of the typeset book. Here is the first page of Peter Adamson’s new book on al-Rāzī, downloaded from OSO:

Yay! No one I’ve queried knows anything about this change, but it’s something to celebrate. OUP’s previous way of making material available electronically was amateurish in the extreme.

I remarked a while back that philosophers might be concerned by OUP’s dominance in the field, and that led to these reflections on the quality of OUP as a publisher. Despite my criticisms, I think the overall news there is quite good. As a profession, we’ve benefited quite a lot from OUP’s consistently high-quality presence in the field.

Still, one might think that this line of inquiry misses what is most concerning in all of this. One of the scholars I surveyed wrote: “The thing that seems bad about the monopoly to me is that people have only one shot at publishing their books with a prestigious publisher. It would be like if there was only one prestigious journal.” Here’s how I would elaborate on that remark. It may be that OUP’s prestige monopoly has progressed to such a point that to publish a book with any other press is immediately a mark against it. It’s easy to imagine, for instance, that when the editors at The Philosophical Review or Analysis look at an OUP book, they immediately lean toward reviewing it, whereas for any other book they immediately lean away (pending further considerations)? What about hiring and tenure decisions? Will a book published anywhere other than OUP immediately look second-rate on a CV? Well, one might say, that’s just how reputational judgments get made all the time, in all sorts of ways. OK, but if OUP is the only high-prestige publisher, and if so much accordingly rides upon its publication decisions, then this is concerning. Even though they publish a lot every year, and even though the scholars I surveyed are enthusiastic about their editorial procedures, it’s problematic if a career can be made or unmade on the report of just a single reader for a press.

I myself don’t think the situation, as it stands, is quite so dire. In the fields I work in, there’s important work coming out from all sorts of presses, and I don’t feel any sense that one must either publish with OUP or perish. But I do wonder whether, in parts of philosophy closer to what’s perceived as the mainstream, the field could be coming close to this sort of alarming situation. Philosophy would benefit, at any rate, from a frank discussion of this issue.

I wonder how far the issue is more about the “decline”, or at least change, in other publishers. To pick an example, it seems to me that Cornell University Press used to publish a good deal of “mainstream” or “core” philosophy books, many of them really very good, but a quick look at their web page seems to confirm to me that they have become much more of a niche publisher in philosophy. It might be that the books they publish are good. But, most of them seem far from the mainstream or core, and I don’t know many of the authors. Won’t that tend to discourage authors from considering Cornell as a place to publish? Perhaps less dramatically, but still noticeably, I think, Harvard University Press has also become somewhat more idiosyncratic in what it publishes. Obviously enough, there are excellent books published by them, but it the “philosophy” list includes a lot of stuff that is somewhat marginally philosophy, and doesn’t cover a lot of areas at all, and it’s not that big of a list in any case. There also seems to be a strong editorial “style” there that is at least less clear at OUP. Blackwell (or whatever big company that owns what was Blackwell calls itself today) seems to have decided to mostly not publish monographs, with a few exceptions, to be sure. Routledge publishes a lot, but many of the books come out only in very expensive editions for a long time. Princeton University Press seems to be the best “competition” to OUP, and I’d rank it as as good or better for many topics (and, the prices are usually better), but it also publishes fewer texts in fewer areas. Cambridge University Press is clearly excellent for many areas, but just doesn’t do as much in as many areas as OUP. We could say similar things about many other presses, I’m sure. I don’t doubt that this can be a downward spiral in many ways, but it does seem to me that the root cause is the decline of many of the other “traditional” publishers. I don’t take this to be disagreeing deeply with the post – but do think that a lot of the emphasis can be put on the decline of publishing options.

Yes. These other good presses are narrow, and getting narrower. It is a bad thing, but this is kind of a weird post—it reads as somewhat critical of OUP, when they seem to be doing everything right. These other publishers are the source of this problem. They’ve left the field of specialist academic publishing, or publish so little that their impact is negligible. What they do publish is often a little weird. I doubt this is because they aren’t getting solicited with good books. If we’re going to look at the problem, maybe ask not “why is OUP publishing so many good books?” but rather, “why are prestigious presses (apart from OUP) publishing so little?”

Very interesting post, Bob, and definitely worth discussing. I’ll just note that the NY OUP office has two other superb Philosophy editors not mentioned here: Lucy Randall and Hannah Doyle. Both are excellent to work with. (And there may be others I’m missing!)

Bob’s figures tell us about OUP’s share of book reviews (in a selection of places). It would be interesting to see a different set of figures: the percentage of a publisher’s philosophy output that is reviewed (again, in a selection of places). As the number of books different publishers publish varies, sometimes dramatically—Princeton University Press publishes around 20 philosophy books per year, compared with OUP’s 200—we may learn that one’s chance of having one’s book reviewed is not correlated with the total number of reviews of books published by your publisher, which may in turn affect what one thinks about whether a publisher has a “prestige monopoly”.

We can praise OUP Philosophy UK&US for their excellent work (by all indications, it is excellent), but monopolies, even benevolent ones, are unhealthy. I’m puzzled by the prestige issue, though – surely monographs coming out of, e.g., Cambridge, Princeton, or Harvard University Press would be no less “prestigious” than OUP? I may well be out of touch with the pulse of our profession, though. I wish “prestige” was not as professionally important as it is, though I may as well wish for utopia, it seems.

OM, you say:

Actually, no, with the near exception of Cambridge UP. It sounds like you are assuming the prestige of a book publisher associated with an institution lines up with the prestige of that institution academically. But that’s not quite right. While a job offer at OUP/Cambridge/Princeton/Harvard might look equally attractive (perhaps even more so Harvard/Princeton!)… a book at Harvard or Princeton is definitely second tier to OUP. Cambridge UP is the closest second. And yet, Harvard/Princeton might be just as esteemed as Cambridge or Oxford academically.

Jorge, I don’t think anyone in this thread has been associating press prestige with institutional prestige. That’s clearly not the OM’s assumption. They’re talking about the presses, presumably because they are familiar with their output.

Saying that Harvard UP or Princeton UP are “second tier” is exactly the sort of narrative that people are pushing against. This might be true, at least in terms of *prestige*, but precisely because prestige need not correlate with *quality*, others have been rightly emphasizing that other presses publish as stellar work as OUP and CUP. So what do you mean when you say Harvard or Princeton are “definitely second tier to OUP”?

I’m not sure how bad the copyediting/typesetting compression problem is. The anecdote sounds bad, but I have a book and a forthcoming co-edited volume with OUP and in both cases, there has been a completely separate copyediting and proofing stage. The copyeditors were great. I’m sure this varies, but I also imagine the more polished the ms sent to the press, the “better” the copyedit will turn out to be.

I stopped dealing with Oxford Press some years ago, after the second printing of my book (The Possibility of Practical Reason) appeared with the wrong title on the cover (“The Possibility of Probable Reason”). When they had to pulp that printing, they jacked up the price of the book to an embarrassing level (over $50, as I recall), and I demanded that they take it out of print. Michigan Publishing took it over as an open-access publication, which is still available as a print-on-demand paperback at a reasonable price.

I think it’s impossible to take proper care with a book while publishing so many at a time. The compressed process described here is a recipe for shoddy work.

A process in which “most unsolicited manuscripts are rejected” is not selective. The basis for soliciting a manuscript is not the quality of the work but the topic and track record of the author. The important number is not the proportion of reviews that are of Oxford books but rather the proportion of Oxford books that are reviewed — and how many would be reviewed favorably if all of them were reviewed.

An Oxford editor once explained to me that digital printing processes make it possible to break even by selling many fewer copies of a book than before, when books were printed from plates. You might ask Peter M. how many copies they have to sell before they start making a profit. To what extent is the rate of 200 books per year driven by money rather than quality?

I recognize that Oxford’s reputation, deserved or not, is still important for authors facing tenure and promotion reviews. I’ve been there, and I get it. Still, if more authors who no longer need a prestigious press would publish their work in open access/print-on-demand format, the open-access publishers could become as selective — and, potentially, as prestigious — as presses who can borrow prestige from their hosting universities while charging for mass-produced “scholarship”. Higher education — and university libraries, in particular — would benefit.

One final note. Open-access publishers usually offer html versions of their content, which is accessible upon publication to low-vision readers using screen readers. An added benefit

One should, perhaps, keep the selection process and the production process distinct.

The most important service provided by OUP is in reliably selecting and publishing good books. And this is not done well by most other presses. Young scholars need OUP because at most other presses, the selection process is uneven and arbitrary. So while it would be good to consider alternative models for academic publishing, it’s not simply the case that ‘prestige’ is what is operative here, so much as excellence in editorial work at the selection stage. That’s not as easily handed off to other presses through a migration of established scholars to those venues.

I appreciate the sentiment, but have to disagree that most other academic presses do not reliably select and publish good books. To suggest that the acquisitions of most other presses are arbitrary and uneven where OUP’s are thoughtful undervalues the expertise of other publishers and overlooks variables like size, resourcing, and the strategic differences between publishing programs. Editorial excellence need not be a binary–OUP absolutely has excellent editors, but that does not mean that the editorial work at other publishers is second-rate. Publishers have different strengths and specialize in different types of publishing–as the article says, “it’s not the case that OUP dominates all parts of philosophy publishing–with regard to textbooks, guidebooks, and translations, they have lots of competition.”

This doesn’t sound to me like OUP has a monopoly problem but that journals like Phil Review and Analysis have a lazy-editor problem. As a book review editor myself (for Kantian Review), I appreciate the temptation posed by the ease of OUP’s (and CUP’s) review copy request forms and their willingness to supply hard copies which are usually preferred by reviewers (tho this is changing in part because of pandemic working conditions). OUP clearly benefits from scale that it can out-compete in these respects, however, their books already enjoy high visibility so I view it as my responsibility to also track what’s being published by other and especially smaller presses (and in languages other than English) and commission reviews for their publications (and when necessary urge reviewers to accept a digital copy).

I’ve written a grand total of one book review, so this is extremely anecdotal, but it was a Routledge book and getting a review copy was like pulling teeth. I filled out the form on their website for this purpose and nothing happened. I sent a followup email and got bounced around for a little while. All told, it took about a month and a half, I think, plus a few emails. If I were a book review editor and I had to do this for every single book from a publisher, I don’t know if I’d call it “laziness” if I didn’t bother doing it a dozen times a year.

I’m the book reviews editor for a niche journal. Some publishers are better than others, but none that I have worked with make it easy. (I think Chicago has probably been the best, in my limited experience.) And just to add complaints about Routledge: they are currently refusing to send physical copies to reviewers. (Their review request form rejects ISBNs for physical books.) If I can’t offer my potential reviewers a physical copy, FAR fewer people are willing to write reviews. So as long as Routledge (really Taylor and Francis) keeps up this policy, Routledge books will be reviewed very rarely, if ever.

A similar experience from the author’s side. I had one book with OUP and one with Routledge. OUP asked me which journals to send it to for reviews, and sent it out promptly after it was published. Routledge didn’t ask, ignored my emails (to 3 different people) about where they would send it, and, as far as I can tell, didn’t send it anywhere.

I’m a Routledge philosophy editor who only rarely commissions monographs, but focus more on all kinds of textbooks, handbooks, and academic trade books. If you want to review one of these types of Routledge publications, and you are having trouble with our online form, please email me directly: <[email protected]> . I’ll need to know the name of the publication the review will appear in and when roughly you expect it to appear. / In fact, if you want to review a scholarly monograph or an academic edited collection of essays, you can email me as well, and I will make sure my colleague, Andrew Weckenmann, gets the message. Andrew W. and his EA, Allie Simmons, are a great team, and usually handle review copies very well, though sometimes things can slip through the cracks for all of us. Thanks!

I have a book appearing with Routledge by the end of the summer (the good Lord willing and the creek don’t rise), and I checked with my editor about hard copies. He said that they’ve been having issues with the online request system, but that he’s able to process requests individually and is happy to send out physical copies to any outlet that wants to review the book.

For what it’s worth, I’ve had a very good experience with Routledge so far, and I certainly don’t think the product is going to be “second tier” or anything. Reviewers and search committees may see things differently, of course, but you can’t control for everything.

I’m about to review a book by Cambridge UP. They were supposed to send me a hard copy; they didn’t. After multiple emails by me, the author, and the journal editor, they sent “another” one. Still nothing. Finally, they gave me a “voucher” for downloading an encrypted pdf version, which can only be opened by 1 software (Adobe something, not their pdf reader), and cannot be marked up at all — practically unusable for reviewing purposes, at least the way I tend to do it (involving markup). Anyway, CUP was a very frustrating experience, and I have heard from some colleagues similar stories. So, there’s that.

FWIW, when I was BR editor for Ethics (2014 to 18?), OUP was the best press at meshing with the way we worked. This involved having my assistant (in a different city than myself) put candidates for review along with relevant links in a database that I could use to decide what to review. The easiest way to get in the database was to send the book to the editorial offices for my assistant to list for me to consider. Also if we then reviewed the book we had it in hand to mail to the reviewer. Other presses sent books, but not as reliably. And many never did unless specifically asked for a copy of a particular book we had already decided to review. (I occasionally bought a book myself if a press did not send it quickly or at all.) Other presses sent links of the sort Aliz mentions, often with expiration dates that made them unlikely to be valid long enough to be easy to use. Other publishers sent emails physical catalogues. We did our best to pay attention to those, but anyone who gets a lot of email knows how much attention a mass email gets when it comes in along with many others in a single day. Author email worked better, and I tried to keep my eyes out at conferences and by perusing websites. But, and this is the point relevant to the OP, making it easier to review a book as OUP generally did, gives one an advantage in having books reviewed. So while OUP would be most prominent without the advantage they get by doing a good job sending out books, doing a good job of that makes it more lopsided when looking at BR numbers.

For most journals BR editor is not a paid position. There is only so much labor a BR editor is going to be able to do to ensure good coverage. Presses can make that easier or harder for an editor.

OUP publishes more monographs than the rest of the academic presses combined. So it’s less a “prestige monopoly” than it just being the biggest. (What if I said Budweiser has the most TV ads, as an analogy?).

There’s plenty of great stuff published by other academic presses; the test here should be what % of books are reviewed in whatever journals, not what the total # of books is. The first would show prestige monopoly (maybe), whereas the latter just shows size. Prof. Pasnau’s analysis conflates these axes.

The prestige monopoly by OUP (and also, but perhaps to a lesser extent, CUP) is real, in the sense that the “evidence of potential for world-class scholarship” for junior scholars hoping to get a job in academic philosophy (esp. in the UK) is increasingly being judged on the basis of “oh, they have a book out/forthcoming? Ah, but it’s not from OUP/CUP, so it must not be that good. If it were world-class, they could’ve gotten a CUP/OUP contract for it.”

Taking publication venue as proxy for quality of what’s published is a terrible methodology, but it’s really hard to argue against in the context of hiring.

“oh, they have a book out/forthcoming? Ah, but it’s not from [OUP], so it must not be that good. If it were world-class, they could’ve gotten a [OUP] contract for it.”

Echoing that this sentiment was expressed by profs repeatedly when I was a grad student at a tippy-top ranked department, just a few years back.

This prestige issue is very real. As an early career researcher, I have been advised by senior colleagues not to write a book, given that it is highly unlikely for it to be published by OUP, and unless it is an OUP book, it’s not worth publishing it, therefore the whole effort is not worth.

I don’t think this is any individual’s or OUP’s fault; I think as a discipline, we are obsessed with prestige.

Sad, isn’t it, how “the shoemaker goes barefoot”? We claim to teach everyone else critical thinking, but we refuse to mitigate even the most obvious biases in one of our most important disciplinary processes (hiring).

For reference, I believe OUP employs as many people as all the other university presses combined (certainly, that was what we were told when I worked there a decade ago). Its capacity to take on work outstrips other university presses by some margin.

I want to petition that philosophy professors not ask their graduate students to do the grunt work of combing through old journals to get data for a blogpost.

Even if they’re paid?

As Chris notes, Research Assistant positions are a common way to give grad students some extra income from a prof’s grant; we don’t really need grad students working in a literal lab, what’s wrong with literally assisting with research?

Given the importance of book publishing for the profession, it would be good to get a sense on the extent to which philosophers of color are represented in the book catalogs. If selection is not blind and it’s done by a small number of individuals, it raises the possibility of bias even if all parties have the best of intentions.

When I was considering where to send my book, I have to admit I didn’t even consider Oxford. I knew it had a reputation within philosophy for being the most prestigious, but it didn’t have a reputation for accessible pricing or for publicizing a book outside of the narrow bounds of academic philosophy. I wanted my book to be read by people outside of the field, so that was a non-starter for me. I approached a press that I knew had a reputation for putting out books at a reasonable price point and that had a publicity team that would try to get the word out about the book–Princeton. I was overjoyed to get a contract there and they have exceeded my expectations.

I guess I would add to this that I know several scholars (including myself) who have tried to get in contact with Peter Momtchiloff to gauge interest in a potential monograph, only to never hear anything back from him despite repeated entreaties. Maybe the potential volumes in question weren’t worthy of consideration, but surely some acknowledgement of receipt of the inquiry is deserved. Given the prestige OUP has, and because most presses don’t want you submitting proposals elsewhere, a lot of scholars can find themselves spending months trying to get a peep out of Momtchiloff, before eventually conceding they should give up and move on to some other press.

That is news, M! A couple of questions and brief comment:

1) Do presses have a policy of not allowing authors to shop around a proposal or manuscript? More senior scholars have often explained to me that it is perfectly acceptable to send a proposal/manuscript to many different presses. Book publishing is very different from publishing in journals.

2) If I have understood Peter’s response to Robert’s queries correctly, then OUP doesn’t accept unsolicited enquiries. Continuing to pester him probably doesn’t bode well.

From this discussion, I think it is reasonable to say that some scholars need to better understand their place in the profession. If I have a good reputation because I publish in only the most elite journals, if I hold a terminal degree from a top-tier institution (think Leiter top-10), and if I have a job at a research University, then I should be highly sought after and solicited by OUP. That’s what I am properly entitled to! No harm in that because I have sacrificed the most in order to improve the profession.

I did a quick survey to see if this intersects with gender (I would have liked to look at race/ethnicity, but that is harder). Looking at books published in the past three months, excluding multiple authors/editors, OUP looks like it has around 68 titles with 31% women authors (using first names as a guide, assuming binary gender for purpose of exercise); CUP has 50 titles with 18% authors (if we include the Elements series, 14% if we don’t); Princeton has 67 titles with 27% women (I dropped dead authors and authors/editors whose names didn’t appear underneath the title in this case). So OUP may be somewhat more gender diverse as well as being more prestigious than at least these two other presses. Of course, this is a small sample in very recent history, so take it with a grain of salt.

I wonder what is the situation in more interdisciplinary (sub)fields. So I went through the journal Bioethics (Wiley). They have been publishing book reviews since 2018 and their book review editor is Professor David Benatar. To this date, they have reviewed 24 books, 14 from OUP. (MIT 3, Routledge 2, Springer 1, CUP 1, Georgetown 1, and two books from the presses I had never heard of).

When I look at my shelves, the overwhelming majority of my philosophy books published in English are from OUP. Many of the most important recent books in animal ethics are from OUP. Yet some of the best books I’ve enjoyed in the last few months, though not in animal ethics, were from other presses, especially Princeton. Based on my totally anecdotal experience, I would say the average quality of a monograph at Princeton might actually be superior to the average quality of a monograph at OUP. I have also read outstanding monographs from Routledge, which also publishes a lot, though quality varies a lot more there.

More importantly, I came her to say kudos to my former student. Nice work, Colton!

Interesting discussion! I have some similar stats at the link below, with a different spin, plus some evidence that when you try to compensate for length of list (which I did imperfectly), Oxford, MIT, Princeton, and Harvard are about equally visible.

http://schwitzsplinters.blogspot.com/2020/05/the-most-visible-academic-presses-in.html

Let me add that I worry that this post might give junior folks the wrong impression that it’s Oxford or bust if you’re looking for the most prestigious venue. I think that is definitely NOT the case. I think the mainstream sense of prestige among research faculty in the US would include at least Princeton and Harvard alongside Oxford, and probably also Cambridge and MIT. I don’t think well informed people will think, “Oh, Princeton? I guess OUP must have rejected the book.” That’s not the situation at all.

I agree completely with Eric here.

Sure, and junior scholars should also know that the “Routledge? Palgrave? Definitely wouldn’t been published at OUP” sentiment is very real.

I published two books with Palgrave that have done very well. Admittedly, I have the luxury of being a full professor, so status seeking is of little relevance. But if you’re only publishing a book for the sake of prestige, I suggest your values are extremely skewed, and skewed in an entirely negative way. Then again, I think pretty much all of academic philosophy has been corrupted by skewed values in this way. (How stupid of me to think that philosophers are interested in truth. Apparently, we’re really only interested in “prestige”.) Meanwhile, the philosophy departments are closing.

I was reporting the sentiment, not endorsing it.

But to play along a bit, is the sentiment that “skewed”? Some philosophers do better work than others. OUP has a long track record of associating itself only with those better philosophers.

I doubt that there’s any non-circular evidence for your claims. And the objections to prestige economies, and the monopolies they foster, are well-known.

The OUP booklist for critical philosophical work on disability is not as good as the booklists on philosophy of disability that other publishers have developed and are developing. For one thing, the heretofore OUP booklist for this area is dominated by nondisabled white philosophers, with (I’m pretty sure) a few more books by such philosophers in the pipeline. It looks as if the editor for the area needs to get better reviewers and widen the scope of the pool of reviewers, as well as the pool of prospective authors. (I think the same could be said of OUP’s feminist philosophy booklist but I don’t address that in this comment.)

Several months ago, I was contacted by a philosophy editor at Bloomsbury who regularly reads BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY and the Dialogues on Disability series and has also read some of my more formal publications. They asked if I would be willing to engage in a brief discussion with them about publishing philosophy of disability. In particular, they wanted to know if I thought there was room on the philosophy scene for another companion, or handbook, or reader on philosophy of disability.

We began a conversation. I explained to the editor that OUP’s recently-published handbook on philosophy and disability was limited in scope, style, topic, and approach to philosophical inquiry of disability, as well as lacked representation demographically. I pointed out that there are relatively few disabled philosophers included in the book; I can’t identify any Black disabled philosophers or disabled philosophers of colour in the book (I know most but not all of the contributors); and the book is largely focused on the (dated?) mainstream concerns and questions with respect to disability of analytic philosophers.

As I pointed out to the editor, furthermore, during the production process, I had repeatedly told the editors of this handbook that they should make the book more inclusive and diverse, should add chapters on gender, race, sexuality, immigration, incarceration, and so on. I also wrote a number of posts on Facebook and on the Discrimination and Disadvantage blog when I blogged there. None of these recommendations seem to have been taken. The end-product is an 800-page book that, with the exception of my chapter and a couple of others, could be mistaken for a collection on philosophy and disability that was compiled 15 years ago or more.

As a consequence of this conversation, the Bloomsbury editor asked me if I would be willing to put together a collection designed to fill the gaps of the OUP handbook and go beyond it, and whether, in addition, I would be willing to write a monograph on philosophy of disability for them. I didn’t even really write a proposal for the collection because they found my criticisms of the OUP handbook and OUP’s booklist in the area so compelling. I sent the editor a list of prospective contributors’ names and the editorial board at Bloomsbury responsible for philosophy enthusiastically approved it. That was it.

We have decided to produce the book as a “guide” rather than a “handbook” in order to keep the price of the book low by publishing in paperback. Handbooks typically first come out in hardcover and are expensive.

I wrote a post about the Bloomsbury collection and its prospective contributors at BIOPOLITICAL PHILOSOPHY here: https://biopoliticalphilosophy.com/2021/05/05/forthcoming-edited-collection-on-philosophy-of-disability/

(I’m undecided about whether I want to take on a monograph on philosophy of disability for Bloomsbury at this time)

I think that a lot of people can relate to this post!

For some reason the link above doesn’t work (at least for me) but I think it should go here: https://biopoliticalphilosophy.com/2021/05/05/forthcoming-edited-collection-on-philosophy-of-disability/ It looks like an interesting collection. I’ll be interested to see the paper on immigration and disability – it’s a neglected topic in the philosophical literature on immigration, and one with lots of interesting and important practical aspects.

Thanks very much for posting the link, Matt.

Shelley

I’m still stuck on the use of “AD” in reference to the century of al-Razi’s birth, in the very first sentence of the Adamson book, which surely should have warranted a query, at the very least, from OUP’s copy editor.

I’d be pretty sure al-Razi would have been a lot more comfortable with it than with the po-faced ‘CE’

That’s a remarkably odd thing to be pretty sure about.

If OUP deserved their reputation, they would undoubtedly employ a team of necromancers to settle questions like this.

How do you know that they don’t?

As a punter who enjoys I reading philosophy, rather than you pros…

I had noticed the preponderance of OUP philosophy books it hadn’t occurred to me that they were more prestigious (as opposed to merely more numerous).

And, although having read all this I now know this was wrong, I did tacitly assume that there was some connection between the status of the UP and that of the department in the corresponding university. I would guess that many non-academics probably make the same error.

I submitted a philosophy book proposal to OUP (UK) just before Christmas, filled out according to their requirements. I haven’t been able to get even an acknowledgement of receipt, despite several inquiries. The arrogance of a monopoly, surely?

A few years ago a good friend had a book published by OUP. He warned me before I bought a copy that the editing ‘wasn’t quite as good as one might have hoped’, or something along those lines. I bought it, read it, and edited it as I went. I was horrified.

He is an accomplished writer whose copy is normally excellent, and yet there were errors both large and small, including a misnumbered endnote halfway through a chapter, meaning that the rest of the chapter’s notes were one out. I told him and this was corrected on second print run. I also asked for the proofs, which he sent, and which I returned to him covered in notes (I am an editor myself). There was at least one error introduced in the published edition that was not present in the proofs. It is interesting to find that this does not seem to have been an isolated incident. Disappointing to say the least.