Philosophy, Imagination, Muscle, Bone, and Science

“My conception of my work doesn’t entail that I think philosophy, in the aggregate, is without practical significance. Quite the opposite. Any institution that encourages imagination and dissolves ignorance is of the first practical importance, and academic philosophy can certainly play a role in that, though one of course wishes the enterprise were less cloistered and classist than it is.”

That’s John Doris, professor of philosophy at Cornell University, in a recent interview at What Is It Like To Be A Philosopher? with Clifford Sosis (Coastal Carolina). It’s a part of his response to Sosis’s question, “How does your philosophical work influence the way you live? How do your non-academic experiences inspire your philosophical work?”

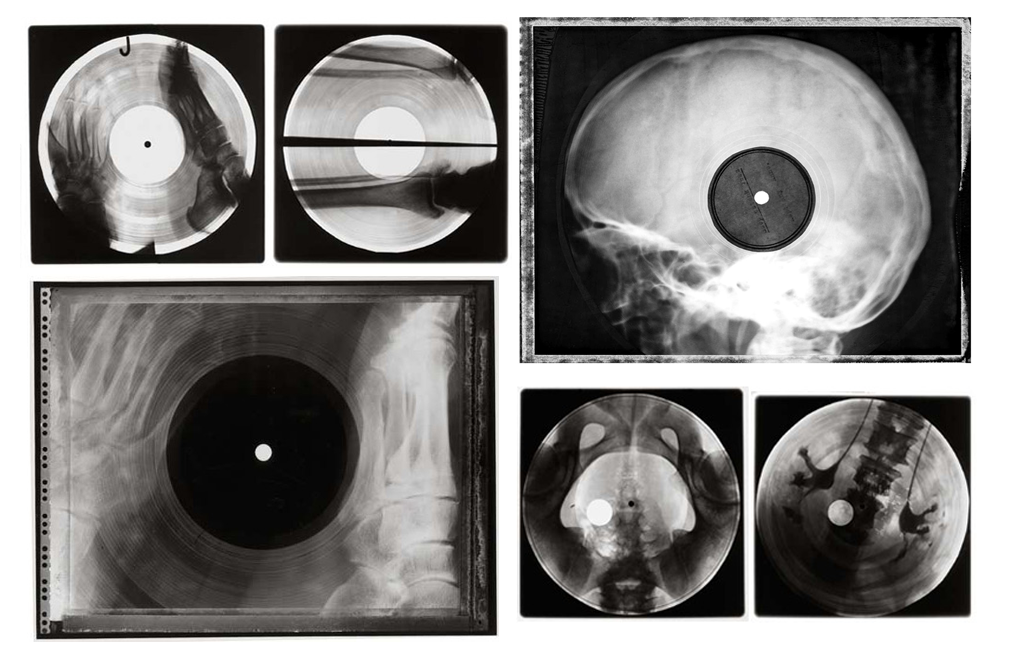

[Recordings of banned music pressed onto discarded x-rays from 1950s USSR (via Colossal)]

Imagination isn’t talked up by many philosophers, or often explicitly taught as a philosophical tool. Why not? I wonder if the tendency of analytic philosophers to see their subject matter as akin to the sciences (and perhaps insecurity about this) leads us to downplay its more creative aspects. (That would be an unfortunate result based on a misleading caricature of science, to which there’d be no shortage of scientists objecting.)

Also in that part of Doris’s answer to that question is a reference to “philosophy with a bit more muscle and bone”:

My experience in the martial arts probably affects how I live more than my academic work in philosophy. The philosophy of the great martial sages tends to be a very practical philosophy. And the practice of martial arts, at least for the dedicated practitioners of traditional disciplines, is a whole life practice in something like MacIntyre’s sense, and I’ve tried hard to practice it…

The distance of much current academic philosophy from thick of life seems to me a very great change from how many canonical figures, notably the Greeks, thought about their enterprise. Of particular interest to me is when and how the body dropped out of philosophy: not as much about gymnastics in Quine as in Plato! There are exceptions, like Barbara Montero, but I’m continually struck by the extent to which contemporary philosophy is disembodied (and maybe has been from modernity forward). I wonder if this is one of the reasons philosophy tends not to speak to the public very well; a good workout may be more transformative than a subtle argument. I’d wish for a philosophy with a bit more muscle and bone, which might (on another unscholarly hunch) make for a philosophy with more compelling contributions to necessities like ameliorating the ever-deepening environmental catastrophe.

I want to know more about what philosophy with more “muscle and bone” is, what forms it might take, and what it might do.

We might ask why contemporary philosophy is relatively “disembodied,” as Doris puts it—or if that characterization is apt, as I can see some philosophers of mind, bioethicists, feminist philosophers, and philosophers of sport, among others, taking issue with it. Perhaps the disembodiment is an effect of philosophy’s concern to distinguish itself from the sciences, and maintain an idea of what is distinctly philosophical (think of when we might hear the question, “How is this philosophy?”).

(Perhaps it’s a mistake to diagnose all of philosophy’s issues in terms of its relationship to the sciences.)

In any event, read the whole interview. It touches on a wide range of things, including how department attitudes towards philosophy vary, advice for graduate students, trends in philosophy, and even philosophy blogs—and you’ll learn about a very nteresting philosopher whose work includes imaginative explorations of our embodied personhood.

Here is another post to tell us that philosophy does not do what it does and should do what it is not supposed to do.

Firstly, imagination has never been as used in philosophy as nowadays. Think about people deploying Walton’s theory of fiction to define scientific models (e.g., Frigg), using imagination as a guide to possibility (e.g.,Chalmers, Kung, Yablo), as a tool to refine our moral sensitivity (e.g.,Nussbaum), a component of empathy (Goldman), a necessary component of perception (e.g.,Nanay), or just people studying imagination in general (there are many books by years, and numerous papers on imagination every year).

Analytic philosophers neglect less imagination than they neglect not to spread banalities like “philosophers should be more interested by the body and being more engaged with the world.”

Secondly, philosophy is not at all disembodied. Think about the neo-Jamesian and attitudinal theory of emotions or enactivism. Of course, some philosophers (maybe too much) tend to neglect the body, but it reflects the diversity in our discipline. Second, if these theories give place to the body, they will not give you Yoga lessons. I am sorry, but if you want to take a Yoga lesson, go to…a Yoga lesson. There is no requirement for philosophy to please people who want to feel relaxed. Looking for it is not a bad thing, not at all, but it is just not what philosophy is supposed to do. Sorry once again, but Universities are not summer camps; neither physics nor English literature aims at relaxing your back or feel good in your shoes. If you think universities are the place to find it, well, it is a category’s mistake.

Third, philosophy should be “more compelling contributions to necessities like ameliorating the ever-deepening environmental catastrophe“. To my knowledge, some philosophers work specifically on that question. Moreover, there is a discipline called “environmental sciences” shaped to help us with that question. There are also politicians and engaged citizens who work at it every day. Once again, that’s all right if philosophers contribute to stopping climate change (as regular citizens or researchers). But, notice how vague Doris’s proposition is – he is not the only person to blame, we can see this kind of trivialities all the time. Okay, we should do more about climate change, but there are several other things to think of, and it is not a shame if it is not directly about saving humankind. Since Plato is used as an authority figure, let me finish my message with a quotation from the Republic: