Two Letters Attributed to Hume Are Fakes

Two letters attributed to Hume are in fact forgeries completed in the late 1960s, according to a study by Felix Waldmann (Cambridge) recently published in the Journal of British Studies.

Dr. Waldmann says that though suspicions about the letters had been raised before, they nonethless have been accepted as authentic by every serious biographical study of Hume since the 1970s, and that their contents and implications have been incorporated into standard narratives of Hume’s philosophical development. In “David Hume in Chicago: A Twentieth-Century Hoax,” he makes the detailed case that they are forgeries, noting that “the hoax is now so thoroughly embedded in the historiography of Hume’s life and writings that scholars no longer realize that they are trafficking in its fabrications.”

Dr. Waldmann describes the letters:

The publication of two previously unknown but substantive letters in 1972–73 was… a moment of tremendous importance for the scholarship of Hume’s life and thought. In the Philological Quarterly and English Studies, the academic Michael Morrisroe recounted his discovery of the letters among the papers of a deceased collector and transcribed each letter with a learned introduction and apparatus. The letters have since entered the standard narrative of Hume’s biography and writings, as monuments of Hume’s correspondence at two crucial moments in his life: visiting Reims as a young man in 1734, and residing in Paris as a diplomat in 1765. Both letters offer a considerable addition to our knowledge of Hume’s intellectual development. The letter of 1734 reveals Hume’s interest in the work of George Berkeley (1685–1753) and his acquaintance with Noël-Antoine Pluche (1688–1761), the author of Le spectacle de la nature (1732–1750). The letter of 1765 shows Hume’s persistent interest in writing an “ecclesiastical history” and his first steps in procuring the scholarly materials necessary for its composition. The first letter, excerpted at length in the second edition of Mossner’s Life of David Hume (1980), is routinely cited by scholars as evidence of Hume’s familiarity with Pluche and his early awareness of Berkeley’s Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge (1710). The second letter, although less frequently cited, features in scholarship on Hume’s historical writing and authorial self-fashioning.

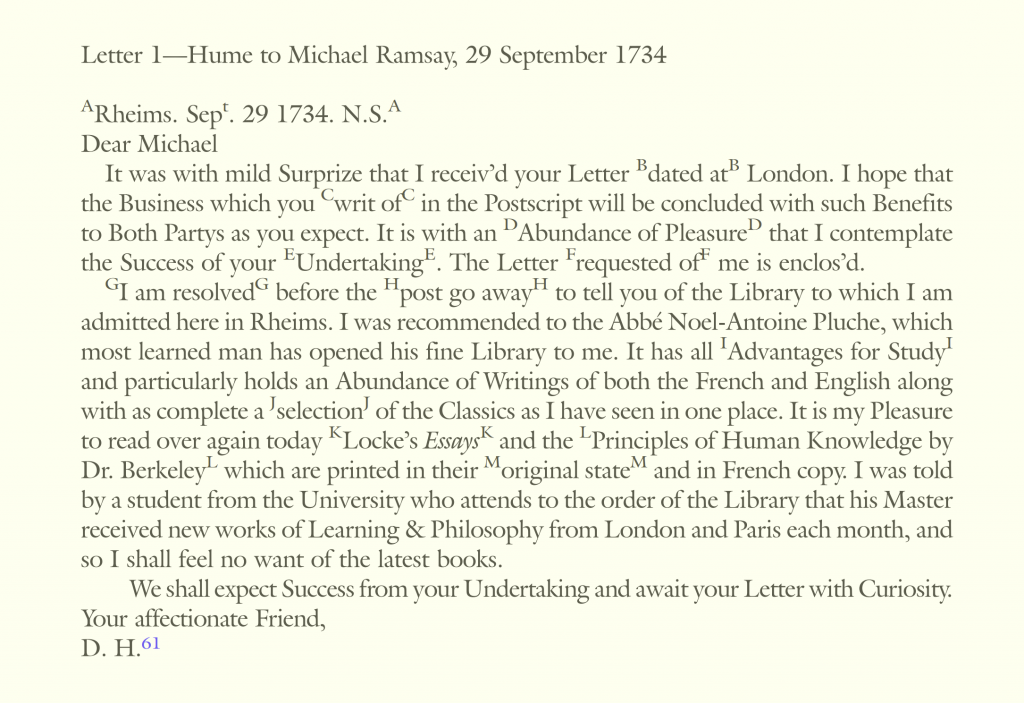

Here’s a screenshot of Dr. Waldmann’s annotated transcription of the first letter:

Dr. Waldmann’s article “reconstructs the history and transmission of Hume’s extant letters and attempts to account for why the forgeries published by Morrisroe were accepted as genuine,” making “a systematic case against the authenticity of the letters.” He also discusses “the implications of the exposé for modern editorial scholarship and intellectual history.” He writes:

The implications of the story told so far may feel familiar. The misplaced good faith of a scholarly community, the authority conveyed by the appurtenances of “good” scholarship, the respectability afforded by the filtrations of peer review: all appear in other recent hoaxes, alongside routine enjoinders for safeguards against further abuse. The exposure of the forgeries published by Morrisroe can only renew these calls for rigor in the assessment of sources, but it can also allow us to revise our suppositions about Hume’s early life and later historical scholarship. We can now revisit the debate over whether Hume ever read the works of George Berkeley. We can reopen the question of Hume’s rémois acquaintance and give new credence to Baldensperger’s conjecture. We can reconsider why Hume might have abandoned his plans to write an ecclesiastical history. And we can continue to rewrite Hume’s biography, in the light of an ever-increasing body of new—authentic—sources.

You can read the whole article here.

When the author says “We can now revisit the debate over whether Hume ever read the works of George Berkeley”, are scholars wondering whether Hume has literally *read* Berkeley as opposed to *merely being familiar* with his work from secondary sources? I was surprised to see that there was a debate given, e.g., the recycling of Berkeley’s arguments and theory of abstract ideas in T 1.1.7 (together with a citation to Berkeley). Either way, really interesting scholarly work!

He basically cites the Principles directly. Obviously he read Berkeley

Waldmann is referencing a famous article by Richard Popkin where Popkin argued that the presence of a citation doesn’t mean that Hume read Berkeley. Many of philosopher’s doctrines Hume mentions could have been acquired second-hand. The appearance of the letter led Popkin to write “So Hume did read Berkeley”. Given that the letter turns out to be forged we can ask Popkin’s questions again seriously. If he was alive he would certainly be delighted by Waldmann’s work..

The letter Popkin cites in his “So, Hume Did Read Berkeley” is not one of the forged letters. The (false) date of the forged letter in which Hume mentions Berkeley is 1734. The date of the letter Popkin cites is 1737. Both are addressed to Michael Ramsey. In the latter letter, Hume suggests that Ramsey read Berkeley’s Principles in order to better understand the “metaphysical parts of [his] reasoning.” The 1737 letter, as Popkin says, is strong evidence that Hume read Berkeley. So there’s still support for the “yes” answer to Popkin’s initial question.

Thanks for the correction Bridger!

This is not really news. At least in the case of the 1734 letter, it was known it was a forgery. James Harris says it in his biography of Hume (p. 490 n3) and he also raises the possibility for the second letter. I also mentioned it in my paper on Hume at La Flèche. The hoax was not publicly denounced as it is now, but no serious recent Hume scholar refers to that letter as a real Hume letter. As for the Berkeley issue, remember that a copy of a 1709 edition of Berkeley’s An Essay Towards a New Theory of Vision with Hume’s bookplate was found in Otago University in 2011.(https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/emxphi/2011/08/a-new-hume-find/)

The article is hopefully clear on your point, Dario. (It should be available OA now.) Harris describes letter 1 as a ‘hoax’, as the article notes. But Harris incorporates one of the letter’s claims – Hume’s meeting with N-A Pluche – into his narrative of Hume’s sojourn in Reims. This is why the letter has to be debunked conspicuously: each of its claims needs to be exposed as false and excised from the historical record. I’m afraid that many serious Hume scholars have accepted both letters’ claims, often unwittingly. The article itemizes each instance. (I also fell victim to the forgeries, although I admit this is hardly evidence that *serious* Hume scholars’ were deceived!)

The Berkeley debate, which is certainly unusual, is whether Hume ‘read’ Berkeley or acquired his knowledge from other sources. Letter 1 has Hume declare that he had ‘read’ Berkeley. The letter of 1737, to which Professor Garrett and Bridger refer, and which was discovered in Poland in c. 1963, intimates that Hume was familiar with Berkeley’s Principles, but in the letter Hume does not expressly state that he read that work or any other work by Berkeley. The copy of Berkeley’s New Theory of Vision with H’s bookplate is not decisive evidence that Hume read that work either. He — or his nephew, the State A/B issue cannot be settled absolutely — owned the copy.

The literature on H as a reader of Berkeley is cited in the article, but copied here for convenience:

Richard H. Popkin, “Book Reviews,” Journal of Philosophy 56, no. 2 (1959): 67–71, at 71; Philip P. Wiener, “Did Hume Ever Read Berkeley?,” Journal of Philosophy 56, no. 12 (1959): 533–35; Richard H. Popkin, “Did Hume Ever Read Berkeley?,” Journal of Philosophy 56, no. 12 (1959): 535–45; Ernest Campbell Mossner, “Did Hume Ever Read Berkeley? A Rejoinder to Professor Popkin,” Journal of Philosophy 56, no. 25 (1959): 992–95; Antony Flew, “Did Hume Ever Read Berkeley?,” Journal of Philosophy 58, no. 2 (1961): 50–51; Philip P. Wiener, “Did Hume Ever Read Berkeley?,” Journal of Philosophy 58, no. 8 (1961): 207–9; Richard H. Popkin, “So, Hume Did Read Berkeley,” Journal of Philosophy 61, no. 24

(1964): 773–78; Roland Hall, “Did Hume Read Some Berkeley Unawares?,” Philosophy 42, no. 161 (1967): 276–77; Roland Hall, “Hume’s Actual Use of Berkeley’s Principles,” Philosophy 43, no. 165 (1968): 278–80; Graham P. Conroy, “Did Hume Really Follow Berkeley?,” Philosophy 44, no. 169 (1969): 238–42; Roland Hall, “Yes, Hume Did Use Berkeley,” Philosophy 45, no. 172 (1970): 152–53.

Felix