A Good Time To Try “Additive Grading” (guest post by Ian Schnee)

In this guest post*, Ian Schnee, Senior Lecturer and Director of Undergraduate Studies at the University of Washington, shares an interestingly flexible approach to grading that might be especially well-suited for a time in which we might expect a higher likelihood of disruption to our students’ lives.

A Good Time To Try Additive Grading

by Ian Schnee

Inspired by Wes Siscoe’s post on pandemic grading, I wanted to share a method I’ve developed that I call additive grading. It is based on ideas in specifications (spec) grading, labor-based grading, and anti-racist writing pedagogies. (For example, see the work of Linda Nilson and Asao Inoue.

Here are the key ideas:

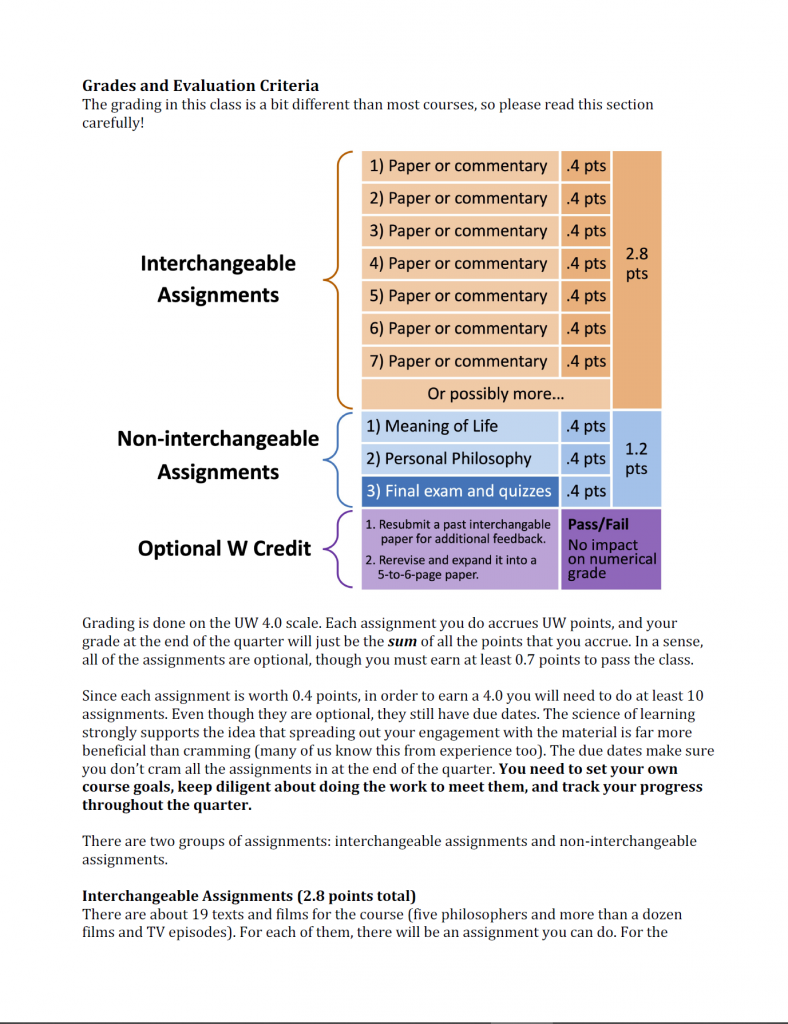

- You grade directly on the 4.0 scale in 0.1 units. All assignments accrue those units, which are simply summed to determine a student’s final grade.

- You offer a large number of possible assignments which allow students to earn units. For example, I offer about 20 assignments worth 0.4 each. In a sense, all assignments are optional. Students set their own goals and have much flexibility in how they meet them. If they want a 4.0, they must do at least 10 assignments in my class, but instructors can modify the specifics in myriad ways.

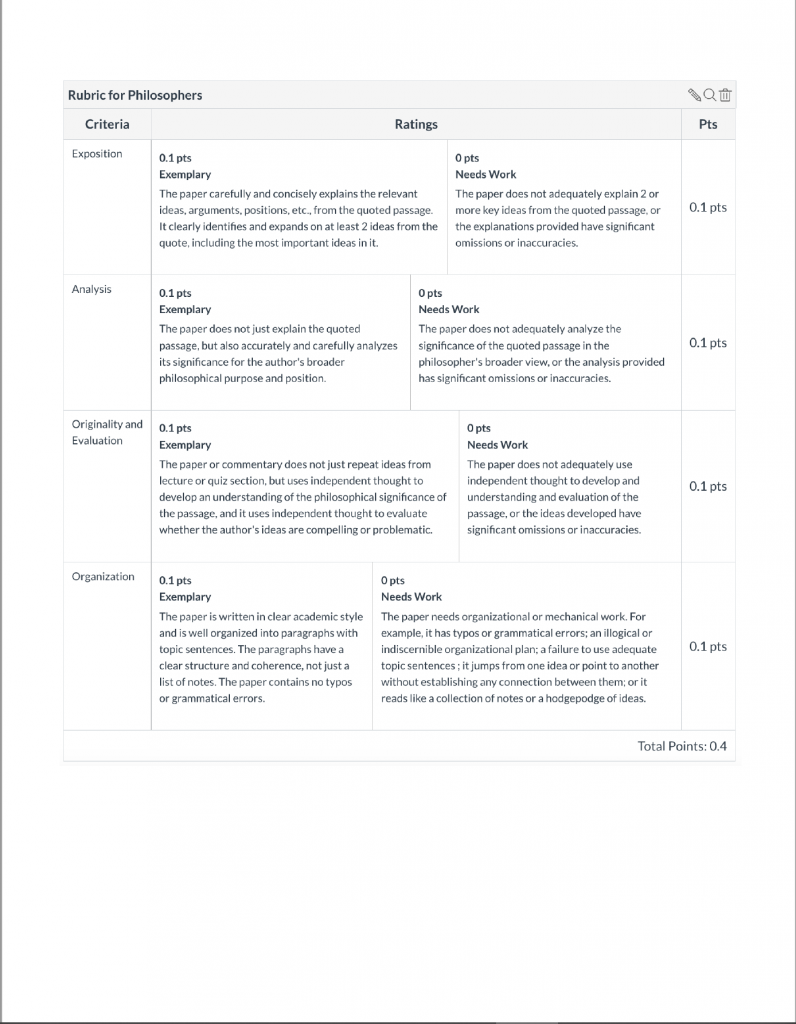

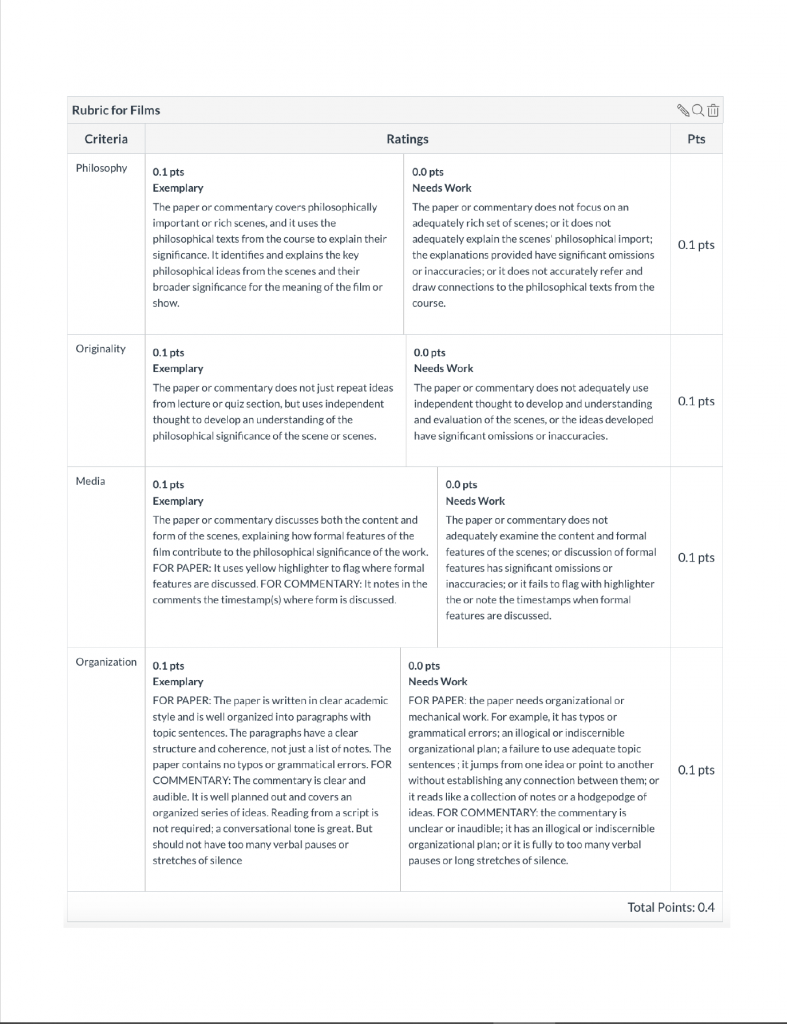

- You use simple, clear rubrics that account for every unit, so grading is very clear and fast, and you can spend your grading time engaging with students’ ideas rather than marking typos or justifying a grade.

- If your school has thresholds, like 4.0, 3.7, 3.3, then a student must meet that threshold in order to achieve that final grade. There is no rounding. At the University of Washington we have a fine-grained system, where a student can earn a 3.8 (e.g.), but there are no grades below 0.7 (other than 0). I know some other schools have a very coarse-grained system, where students can only earn 4.0 or 3.0 or 2.0, etc.

I used this system in a 100-level philosophy course in Spring 2020 (large lecture course with 200 students and TA help), and I’ll be using it again in Fall 2020 (300 students). It received a very positive response from students and TAs. Some advantages for students:

- They have a lot of flexibility in when they do assignments.

- They have a lot of agency and self-direction, choosing assignments they are most interested in.

- No assignment can hurt a student’s grade, so students do not feel stress or jeopardy doing any assignment.

- The system is very transparent, and students can understand how their work directly contributes to their final grade.

A couple of objections and replies:

Objection 1: Students won’t do the reading/work unless there is an assignment directly tied to it.

Reply: This did not turn out to be true in my class. E.g., student rates of viewing online lectures were good, especially given the circumstances this spring.

Objection 2: Students won’t learn writing skills unless they get detailed feedback on their writing.

Reply: I am actually highly skeptical of the value of the traditional approach to grading writing in philosophy, which is lots of comments and exhausting work for instructors. Many students look at the grade and don’t read the comments. Many cannot transfer those lessons to a different paper on a different topic weeks later. Etc.

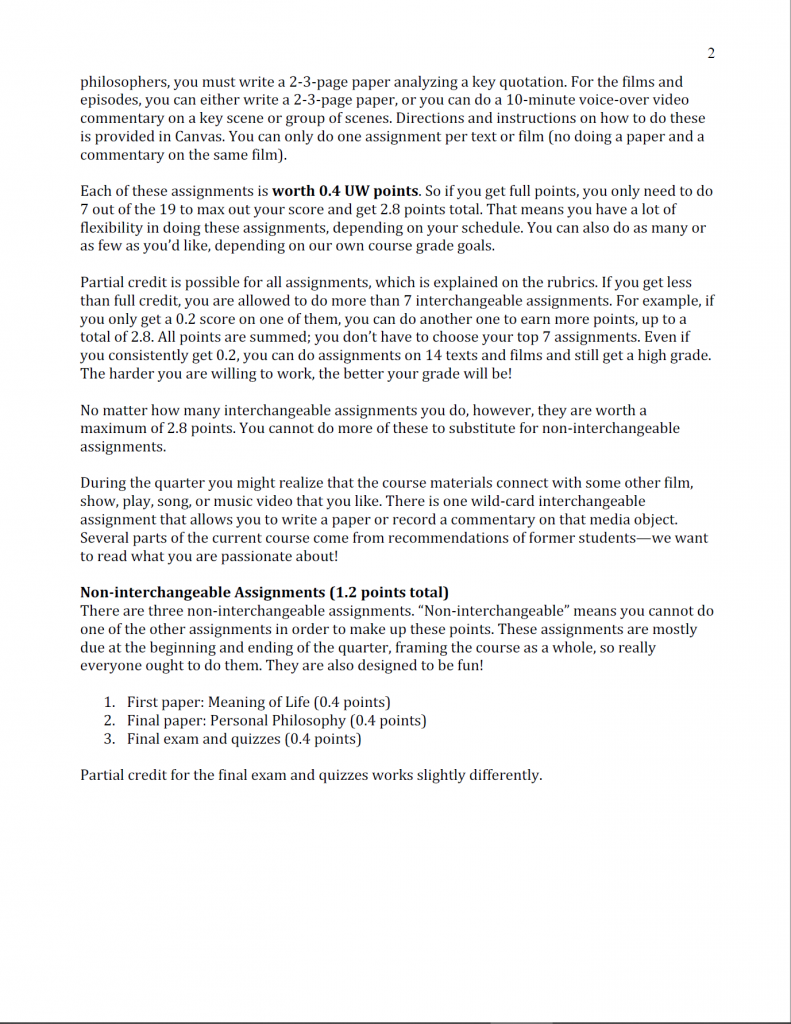

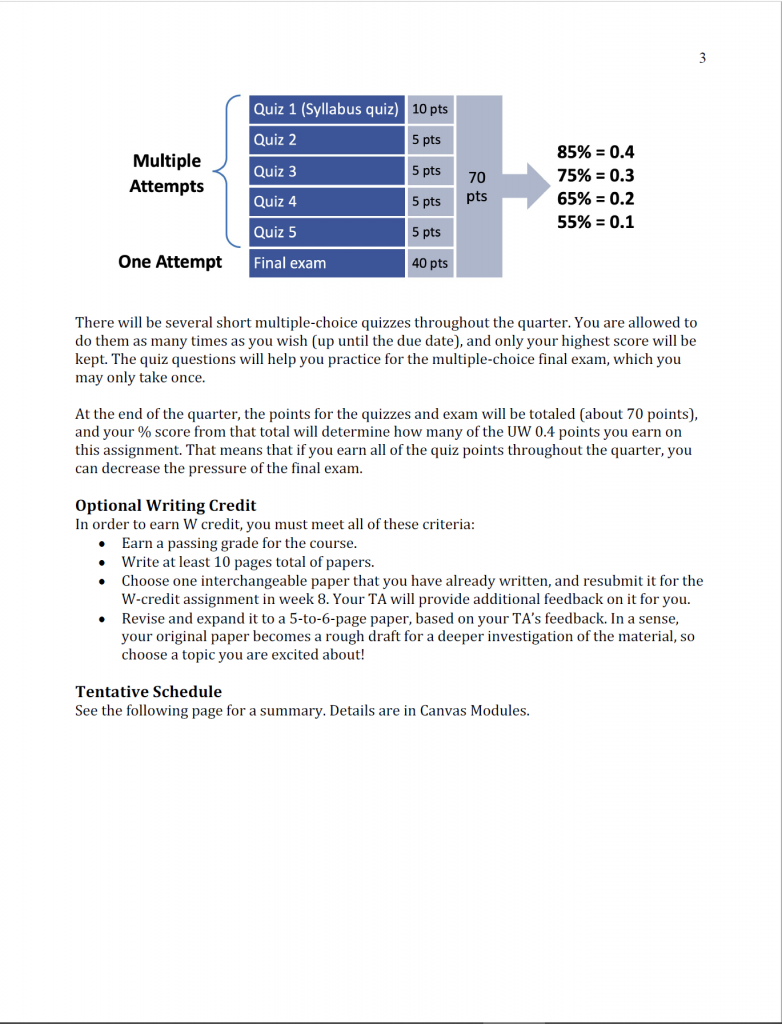

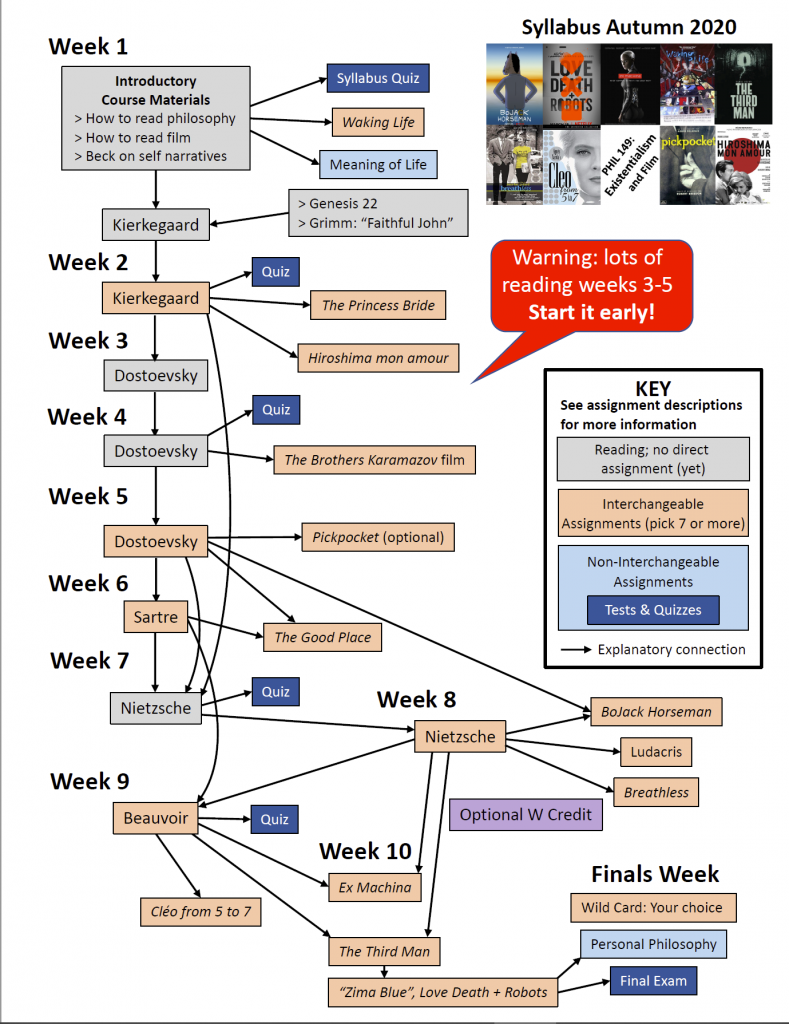

To see what additive grading looks like in a specific application, here (as PDF) and below (as images) is an excerpt from my syllabus for PHIL 149 at UW, which also includes two rubrics. (For teaching, treat this as an OER—open educational resource—and copy, paste and modify without attribution; for SoTL please cite.)

This is excellent. I’m a fan of innovative grading practices. Additive grading, as shown in the post, strikes me as quite similar to William Rappaport’s “triage theory” of grading. Additive grading is structured around a series of plus/minus grades, and it uses a straight sum to map those grades onto traditional letter scores. Triage grading is slightly more complex, but also for that reason a bit more flexible. It is structured around a series of check-plus/check/check-minus grades (for “clearly excellent, neither clearly excellent nor clearly poor, and clearly poor). It uses a straight sum to calculate a point total, and then a formula to map the point total onto traditional letter grades.

I’ve been using triage grading for several years, with good response from students. Like additive grading, it makes transparent what assignments and grades students need to achieve for specific letter grades, and it informs decision-making about which assignments might be left undone. This is a big selling point for students. Another is that students tend to appreciate the way in which it cuts down on subjectivity: I’m a very good judge of the difference between check-plus, check, and check-minus work. (So too with plus vs. minus.) I’m less of a good judge for the difference between an 89 and a 90, or between a B+ and a B- (and even A vs. B).

Triage grading strikes me as having two virtues that aren’t obvious with additive grading. First, the mapping doesn’t so severely constrain the total number of assignments you’re able to give. Because triage grading using a mapping to correlate point totals to letter grades, you’re not constrained in the total number of points available for students to earn. (You also can build in flexibility by not having all graded work count toward the point total–using “best 4 of 5” sort of strategy.) I suspect there’s a way to tweak additive grading to have this virtue, though.

The second (potential) virtue is that the third value permits slightly more refined judgments of quality. One concern is that the plus/minus system encourages students to cut their effort when they’ve met the baseline for not receiving a minus. The difference between check-plus and check, in triage grading, avoids doing this, especially if you specify that “clearly excellent” means something like “clearly excellent in relation to work by your peers” (but not necessarily only in this way). I don’t have any experience with additive grading, so maybe this isn’t a pressing concern. But if it is, I don’t see how to avoid it with a two-mark system without being overly harsh with the standard for receiving a plus.

Hi Nick–thanks for your detailed reply! Yes, triage grading is precisely one of other precedents I could have included along with Nilson. I prefer a points rubric rather than a check/plus/minus system, but I take these to be minor variations still in the same camp, as you note, that differs quite radically from how grades are traditionally handled in departments. The pandemic has made me all the more interested in pursuing these sorts of approaches.

I’m not sure those are the forceful objections. I proposed a similar grading scheme like this on a course proposal and got some pushback from our curriculum committee. The primary objection was that a 4.0/A is the way to signal that a student has understood all of the concepts in the course with a certain proficiency. So, for example, take an introductory course in logic. In theory if it were graded like this, a student could earn a 4.0/A without even bothering with the predicate logic section of the course.

As long as a student knows that skipping certain parts or otherwise failing to master them will cause them problems in future courses that build off of that material, it seems perfectly reasonable to allow a student to focus on what s/he wants in the course and earn the A. I’d rather have students learn 3 concepts really well and earn an A than 5 less well and earn that same A.

I’ve only just heard of this idea and haven’t spent time working with it, but it seems that there are ways to overcome this objection (as I’m sure you’ve already thought of as well). In a logic class, one way to do this would be to create an excess of tests, adding up to 6.0, with only 3.0 worth of points available from propositional logic, and the other 3.0 worth from predicate logic (or the last few weeks of material generally). A student who does badly on the early material would still have a chance to study hard and take extra tests on the later material to try to make up the total score, but a student needs to do at least a third of the tests from each set of material in order to get an A.

There’s probably still problems with this (a student who does great on propositional logic but only barely gets predicate logic, might be able to make up that last 1.0 with a bunch of flailing on the last few tests, if there are enough points available on those last few tests for someone to make up for having done badly early on. But I suspect there are some clever ways around this, perhaps if you have to do well on at least one test in predicate logic to “unlock” some of the additional tests available for additional points later on.

Hi Chris–yes, that ability to grade like this can vary by department. My first reaction to your CC’s stance is that it couldn’t hold across the board. I don’t think any course in my department evaluates to establish that “a student has understood ALL of the concepts in the course with a certain proficiency” (my emphasis). One way to handle the logic case is similar to what I do in the syllabus above with the final exam. So you could make problem sets “more” optional, the way I treat papers. But a student couldn’t get a 4.0 without doing well on the exam.

Maryellen Weimer discusses this sort of approach tplo grading in her book, Learner Centered Teaching. I have researched this approach in multiple semesters of my own teaching and recently published a paper about it. https://www.pdcnet.org/aaptstudies/content/aaptstudies_2019_0005_0068_0088

Perhaps this will be interesting to those of us intrigued by this approach to organizing the graded work in our classes. It certainly has benefits, but there are some drawbacks that are worth considering.

Hi Andrew–good points, there are lots of great precedents here I’m drawing on. I look forward to checking out your article!

Great post! I worry that the way this is drawn up currently is a little too confusing for the students. But it has some nice features, chief of which is that no particular assignment is required. [the charts are helpful to me but I’d want much simpler versions of them on my syllavus]

Hi Kevin, that’s for replying–yes, fair point. Hopefully folks can see that there are much simpler ways to implement the idea than the way I chose!

This looks great, Ian! I especially like how you pair the interchangeable assignments with required assignments, providing the students with a lot of choice and self-direction while at the same time insuring that particular important benchmarks are met. One question I had was about TA consistency. In order to provide consistent grading across multiple graders, my TAs will typically have a check in when they are all grading the same assignment to make sure they are giving roughly the same marks. How have you dealt with that across all of the optional assignments?

Hi Wes–we had fewer problems with TA calibration with this approach because the the rubrics were so simple (four binary criteria). We didn’t do assignment-by-assignment calibration. I personally find it difficult to apply rubrics with large point ranges, which I’ve seen cause a lot of wasted effort before. Another factor is that we graded generously, with almost all students getting 0.4 on an assignment. At the beginning of the quarter, that wasn’t the case, we gave of 0.2s or 0.3s, which I didn’t feel bad about because they can do more work to make up the points. But my application was fairly labor-based: lots of 0.4s and thus not much calibration worry.

This was very helpful – thanks again for the great post!

I’ve used this type of grading for a long time, so I’ll add some thoughts. I teach accounting to Executive MBA students, so your mileage may vary, but more due to the maturity of my students than the content. (I teach accounting like practical philosophy, as you can see from my <a href = "https://ssrn.com/abstract=2899141"free textbook).

The concern about grade inflation is a real one. I addressed it by creating the additive point system but not guaranteeing anyone’s grade. They worked way harder than ever, but it was really stressful for them. So I looked at how many points earned them an A, A-, B+, B or B-, added about 25%, and asked my program director if I could guarantee that someone how earned enough points could get that grade. I’ve upped the thresholds every term and still give out a very high average grade, but the students are now working about 50% harder than they did the first term. (A+ and grades below B- are judgment calls.)

Unlike the original post, I provide an enormous number of assignments. I call it the all-you-can-eat buffet. There is way more content, and way more assignments, than any reasonable person would tackle. Like the OP, I have different categories, so students have to do at least a little of everything. But the only thing keeping someone from an A is effort. I always have some students who do *everything*, and earn an A+.

I don’t think it’s too common to have quizzes in philosophy, but some of you may want to reconsider. Quizzes are great for making sure students understand the basics: terminology, frameworks, history, computations (for philosophy that might be analyzing logic), etc. I have about 35 topics, each with a question bank of 25-50 questions. For each topic they take 3 quizzes that draw 5 questions randomly from the bank. The Bronze (first) quiz is worth 1 or 2 pts a question, which is doubled for the Silver and doubled again for the Gold. This gets them to engage repeatedly with the material, which is really good for learning and retention.

My typical term is 12 weeks. I have an online discussion board for each week, but they can only earn so many points from that—some for writing posts, some for commenting on others. I use a very simple grading system: a good effort in good faith earns full credit. When I switched to this system (rather than trying to figure out the difference between an 87 and 93), quality improved dramatically, because students stopped trying to figure out what boxes to check, and instead worried about what I and their classmates actually thought of their contribution. Lots of students write way more comments on others’ work than they can get credit for.

Btw, this approach has worked especially well during the switch to online teaching.

Hi Robert–this is really great, thanks for sharing your experience. My grades were higher as well, which I wasn’t sure how to interpret since it was an unusual spring quarter (on account of the protests, our school recommended making the last week and final exams optional, which we did). I really enjoyed reading that your students are working way harder. If that is true, then I am happy and don’t worry about grade inflation, but I know that is not a widely shared view. And like you say average grades/grade inflation isn’t always an individual decision. I think a lot of instructors/departments will be grading more generously this coming year, so additive grading could be worth trying now more than before.

I also completely agree with you about quizzes. I don’ think quizzes are the only good approach (e.g., Socratic note taking by Mark Walker 2017), but they are a very valuable tool.

I’m sympathetic with what you say about the traditional way of teaching writing in philosophy courses but your rubric doesn’t seem to show how your method works as an alternative. Each rubric item contains the word “adequately,” and it seems like you’d have to spend the same amount of time as usual explaining to students what “adequately” means in marginal comments! What are your thoughts about this though?

Hi Kris–thanks, I really agree with you about showing students what we mean. My approach is to make my own example papers and commentaries. On the rubrics then we didn’t provide much feedback. There were a few common problems, like students not discussing the formal features of a film at all, so we just copy and pasted that note on the rubric feedback. Fair point about “adequately”. Since we were using a largely labor-based model, the bar for adequate was not super high.