Public Philosophy and the News (guest post by Alexis Papazoglou)

Philosophy still can, and should, be done in the service of helping others make sense of our contemporary shadows on the wall: the never-ending news cycle.

The following guest post* is by Alexis Papazoglou, a philosophy instructor-turned-writer whose work on the intersection between philosophy, current affairs, and politics has been published in The New Republic, The Atlantic, and The Philosopher. He is currently writing a book introducing philosophical questions through stories in the news. His handle on Twitter is @philosgreek.

This post is the sixth installment in the “Philosophy of Popular Philosophy” series, edited by Aaron James Wendland, a philosopher at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. Follow him on Twitter: @ajwendland.

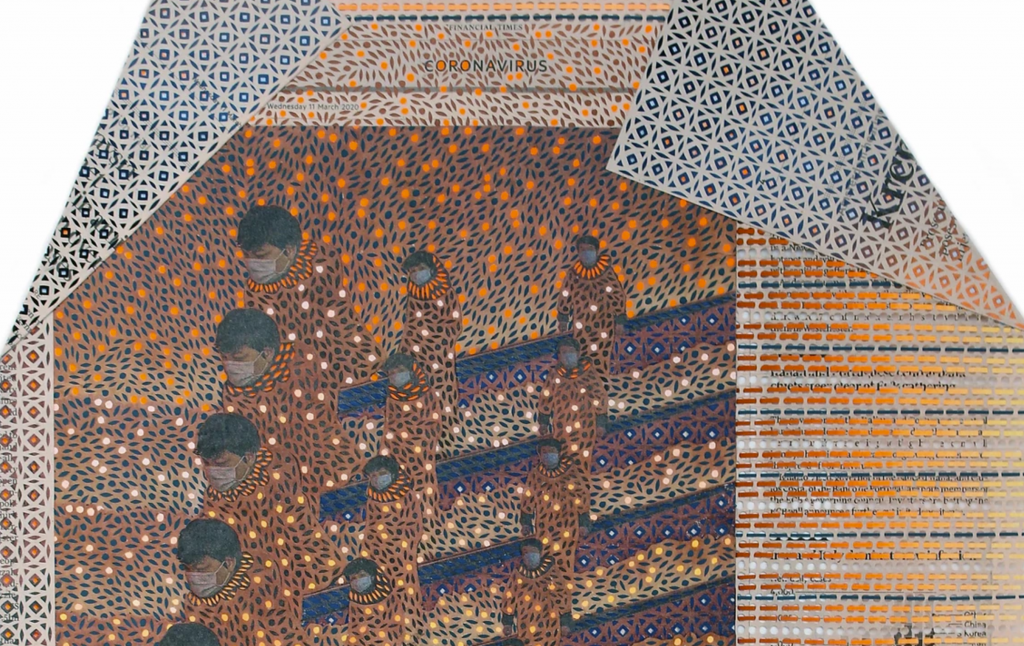

[Myriam Dion, “Coronavirus – China’s risky plan to revive the economy, Financial Times, 11 March, 2020” (detail)]

Public Philosophy and the News

Alexis Papazoglou

The belief that philosophy should have a public side, engaged with an audience of non-philosophers and in the service of a public good, is as old as the subject itself. According to the most famous metaphor about philosophy, Plato’s allegory of the cave, philosophers are duty-bound to share their findings and help others see beyond their everyday experiences, the shadows on the wall.

Plato painted a particularly flattering image of philosophers, picturing them having access to a whole other level of reality, outside the cave, where the sun is shining and the objects are real, unlike the wooden replicas and puppets whose shadows are the only thing prisoners held captive in the cave can see.

Few philosophers buy into the idea that their training affords them access to a Platonic realm of absolute truth, separate from the one of everyday experience. But philosophy still can, and should, be done in the service of helping others make sense of our contemporary shadows on the wall: the never-ending news cycle.

The image of people captive, with their heads directly in front of a screen, makes it hard to resist drawing this analogy with Plato’s allegory: Our phone and computer screens are our contemporary cave wall, and on them we witness the dimly lit projection of everyday reality, a relentless stream of events, news, and information.

This constant flux was one of the reasons Plato believed the everyday world to be illusory, the domain of mere opinion, not knowledge. Indeed, today’s main attempts to make sense of the moving images and symbols on our screens are called opinion pieces. Commentators offer their perspectives on the latest events, usually in line with their partisan beliefs. But even Plato, who had a real disdain for the everyday world, thought philosophy could do better than offer mere opinion about it: It could ultimately be a guide to helping us understand it.

The news might seem like the most unphilosophical topic—it’s about contingent events, particular people and situations, whereas we usually think of philosophy as Plato did, being about necessary and timeless, universal truths. But according to a very different philosopher, the 19th century German idealist Hegel, philosophy is not a practice detached from the happenings of history, politics and culture, but the lens through which we can understand our times.

For Hegel “philosophy is its own time comprehended in thought”. A case in point is Plato himself. Despite thinking philosophy was the contemplation of eternal truths, Plato’s work was very much a reaction to the cultural and political moment he lived through in Ancient Athens. It is, after all, hard to imagine Plato’s critique of democracy without the execution of Socrates.

Philosophical questions don’t suddenly appear in a vacuum, they lie beneath the surface of more familiar questions that daily events and developments pose to us. Should one have children, given the looming climate change catastrophe? Do we control our use of smartphones, or do our smartphones control us? What does it mean for policy makers to “follow the science” in response to a pandemic?

These questions, already present in the lives of people engaged with the news, are an excellent way to introduce philosophy to a general audience, inviting them to see abstract questions about the ethics of reproduction or the unity of science behind more specific ones. “Is it better to never have been born?” “Do all scientific findings have the same degree of validity?” These philosophical questions might seem too far removed from everyday concerns to be of interest to the uninitiated, but demonstrating their connection to news stories can be a gateway to caring about questions that were previously left to the specialists.

Pressing questions arising out of our current historical circumstance can also act as new starting points for contemporary philosophers. The use of Artificial Intelligence in the justice system gives rise to new contexts for thinking about bias and transparency in judicial rulings. Similarly, the mass surveillance of individuals via their online footprint requires us to rethink the relationship between privacy, power and autonomy.

Finally, paying attention to these more local questions is a reminder to philosophers that scholarly, technical discussions have more down-to-earth origins, and that philosophy should ultimately be able to relate back to those origins, to the world we live in. Philosophy might temporarily step back from the contingent, everyday world, but only in order to make sense of it.

Philosophers, of course, don’t have all the answers to the various questions plaguing our current predicament. Their aim might be the truth, getting things right, but the variety of arguments and conclusions reached suggests that the value of philosophy can’t simply be the end results, the findings. Instead, what philosophers are good at is revealing the complexity of a question, dissecting the structure of arguments, drawing conceptual distinctions and reminding us of the ideas of past philosophers, in order to shed light on an issue.

When these skills are applied to analysing the news cycle, there is an opportunity to go beyond mere opinion pieces, the personal beliefs of someone, and towards something closer to understanding. Appreciating the complexity of a question allows us to see through dogmatism, breaking down arguments reveals their weak points, drawing distinctions helps us avoid oversimplifying concepts, and the history of philosophy acts as a reminder that there are alternatives to our current way of thinking.

The news cycle therefore provides a double opportunity for philosophy: to renew the urgency of philosophical questions by linking them to contemporary concerns, but also to show the need for philosophy’s tools to the uninitiated, if we are to make sense of the world that goes by our screens every day.

Even though today’s academic structures do not encourage philosophers to produce popular work that engages with current events, it is one of the most valuable public services they can provide. Philosophers shouldn’t linger outside the cave for too long, discussing amongst themselves—the point of philosophy is to help others understand what’s going on inside it.

Well, here are a couple of questions:

(1) Why do you think that philosophers are particularly well-equipped to achieve “understanding” of these kinds of worldly topics, given that we receive no training in empirical analysis whatsoever?

(2) Do you think it’s a problem that professional academics are, as a rule, highly unusual people who are fairly disconnected from the material realities of “our time”? Perhaps we can get around (1) and say that there is some sense in comprehending a time purely “in thought”. But why think that our thinking is particularly well-positioned to see what “our time” really is like? We are generally a really weird bunch of people, even those of us who try to signal otherwise by including hashtags and pop culture references in our talks.

Great thoughts! Another extension from Plato that is worth considering is the extent to which philosophers might cut through shadows by actively constructing coherent conceptions of the (common) good. What kind of world do we want to make? How would our politics have to change in order to more adequately address public health, climate change, the emergence of AI, systemic racism, police violence, etc.? How would our educational, economic, or cultural systems have to change? These are questions of institutional and socio-political structure rather than individual behavior (c.f. above “should one have children…?”). The fleeting, transient, ever-changing images on the cave (or, iPhone screen!) are sources of confusion, in part, because they do not provide insight into the fundamental sources of this diverse mixture of apparently disconnected events and episodes. Plato seemed to think (though maybe he was wrong!) that we won’t gain insight on such fundamental sources until we first spell out as completely as possible our highest socio-political ideals, and then use this picture as a measure against the status quo. We can do this without buying into the less popular Platonic-metaphysical doctrines, e.g., “the idea that their training affords them access to a Platonic realm of absolute truth, separate from the one of everyday experience”; and can likewise extend the general method to problems that Plato couldn’t have anticipated (such as those listed above). This seems preferable to the Hegelian optimism that history is itself dialectical and conflicts/contradictions will resolve themselves in due course! Dialectic, for Plato, is the ultimate tool of philosophers, and perhaps necessary for the changes that are needed today.

“Finally, paying attention to these more local questions is a reminder to philosophers that scholarly, technical discussions have more down-to-earth origins, and that philosophy should ultimately be able to relate back to those origins, to the world we live in. Philosophy might temporarily step back from the contingent, everyday world, but only in order to make sense of it.”

Some parts of philosophy, for sure. It doesn’t apply to, e.g., most philosophy of physics.