Philosophical Intuitions Are Surprisingly Stable (guest post by Joshua Knobe)

There seems to be a very general pattern whereby the tensions in people’s intuitions tend to be surprisingly stable across both demographic groups and situations.

The following is a guest post* by Joshua Knobe, professor of Philosophy, Linguistics. and Psychology at Yale University. A version of it first appeared at The New X-Phi Blog.

Philosophical Intuitions Are Surprisingly Stable

by Joshua Knobe

When it comes to many philosophical issues, people feel conflicted or confused. There is something drawing them toward one intuition but also something drawing them toward the exact opposite intuition. This tension seems to be an important aspect of what makes us regard these issues as important philosophical problems in the first place.

In a new draft paper, I argue that experimental philosophy research over the past decade or so has shown us something very surprising about these issues. It has shown that the tensions in people’s intuitions are themselves stable. In particular, these tensions seem to be surprisingly stable both across different demographic groups and across different situations.

To illustrate, consider the problem of free will. Existing studies on people from Western cultures indicate that there is a tension in their intuitions. There is something is drawing them toward compatibilism but also something drawing them toward incompatibilism. More recent studies have shown something very surprising about that tension. The tension seems to itself be stable across cultures. In other words, it’s not as though there are other cultures in which just about everyone thinks that compatibilism or incompatibilism is obviously right. Rather, people across numerous different cultures seem to find this issue confusing, and in much the same way.

The core claim of the paper is that a whole series of different studies, in completely different areas of experimental philosophy, have been providing evidence for that same conclusion. There seems to be a very general pattern whereby the tensions in people’s intuitions tend to be surprisingly stable across both demographic groups and situations.

Just as a quick teaser, I thought it might be helpful to include some data about the surprising ways in which experiments over the past ten years or so have shown intuitions to be stable across situations.

- I used to believe that you could change people’s moral intuitions around by putting them in situations that affected the degree to which they experienced disgust. So I thought that moral intuitions could be affected by washing one’s hands, drinking a disgusting beverage, or just being next to a hand sanitizer.

Amazingly, all of those effects have failed to replicate. It now looks like intuitions are not affected by washing one’s hands (Johnson et al., 2014), or by drinking a disgusting beverage (Ghelfi et al., 2020), or by being next to a hand sanitizer (Burnham, 2020). Moral judgments seem to be a lot less sensitive to manipulations of the situation than many of us thought they were.

- I also used to think that people’s epistemic intuitions could be shifted around by manipulations of the vignette they saw previously. The thought was that a confusing vignette would look a lot more like knowledge when it came directly after something that was obviously non-knowledge and a lot less like knowledge when it came after something that was obviously knowledge.

That effect, too, has failed to replicate. Here are the latest results from Ziółkowski et al.

- Finally, a large body of evidence suggests that people are drawn toward one moral view by System 1 processes and toward another moral view by System 2 processes, so I used to think that any manipulation of the situation that increased System 2 cognition would shift people’s judgments around.

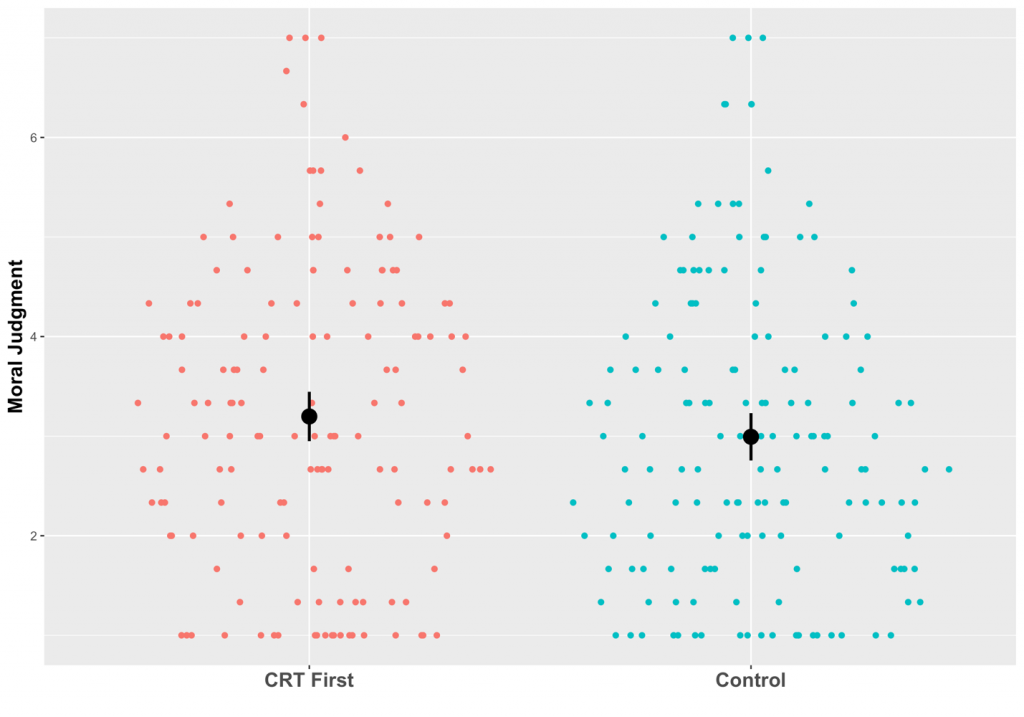

An important study seemed to suggest that there was indeed such an effect, but once again, that study has failed to replicate. Here are the results from Cova et al. (2018):

I am very uncertain about how to explain all of these results, and I remain agnostic within the paper itself. But it does seem that we can’t just keep philosophizing about the effects we used to think existed. We need to start engaging in a more serious way with the growing body of evidence that suggests people’s intuitions are surprisingly stable.

Why is stability here surprising? What was the reason to expect instability?

When I first read the title of this post, I thought it was about philosophical *Institutions* – if only!

Hi David,

Great question. The answer is that certain existing theories, which were based on previous experimental studies, seemed to predict instability in many of these cases.

For example, existing theories suggest that (a) the more people use System 2, the more they will have ‘consequentialist’ intuitions on trolley problems and (b) going through the cognitive reflection test (CRT) makes people more inclined to use System 2. Together, these two beliefs led many of us to expect that people’s trolley problem intuitions should be unstable in a certain way. Specifically, we expected that it would be possible to shift these intuitions around just by giving people the CRT.

But the results did not come out the way we expected. Instead, people’s intuitions turned out to be stable across this manipulation. Other roughly similar cases showed that same sort of pattern. It seems like you can change people’s situation around in all sorts of ways that you might have had good reason to expect would shift their philosophical intuitions, but people‘s intuitions tend to remain remarkably unaffected.

Very interesting! I wonder if someone could object by saying that the problem of replicability affects nearly all scientific disciplines, so it’s a little unfair to level this charge against one discipline in particular. At the very least the defender of intuition relativism (or something like that) could just punt the problem down field to the other sciences.

Hi Joshua,

Good point. In the paper, I emphasize the difference between two different kinds of experimental philosophy studies:

(1) On one hand, there are studies in which researchers manipulate something in the actual vignettes or questions that participants receive (e.g., randomly assigning participants to one or another version of a vignette where these versions differ on some specific dimension).

(2) On the other, there are studies in which the actual vignettes and questions remain word-for-word the same in all conditions, but researchers manipulate something about the external situation (e.g., changing something about the conditions in the room, or the materials participants receive just before getting the vignette).

Existing research shows that studies of type (1) have a pretty amazing track record of successful replication. For example, a recent paper by Cova et al. replicated a series of studies about type and found that 90% of them successfully replicated.

Thus, the surge of replication failures for studies of type (2) can’t just be due to some very general problem whereby lots of studies fail to replicate. it seems to show something specific about that one particular type of study.

Hi Joshua!

Thanks for posting this stuff. I work in this area (x-phi / moral psych) and appreciate your contributions to it immensely. I’m always skeptical of arguments against an effect that rely on citing a single study that seems to speak against it (people used to think x but this one study said ~x so x doesn’t replicate!). I wonder if you have know of anyone who has (or is doing) a meta-analysis of situationist moral psych research? I know that meta-analyses have problems of their own but it would be helpful to get the bird’s eye view of the field that these studies can offer.

It isn’t that I’m saying you’re wrong to think that intuitions are more stable than they seem (I mean…they could be and they might not be if we’re using one or another individual study or small set of studies to ground our claim); instead, I guess I’m wondering whether it isn’t (way) too soon to be making claims like this at all.

Hi Caligula’s Goat,

Excellent point, and I certainly appreciate your call for caution.

Within the existing literature, each of these effects has been discussed more or less in isolation from the others. So there is a literature on the impact of incidental disgust on moral intuitions, then a separate literature on the impact of order on epistemic intuitions, and so forth.

Within many of these separate literatures, there have been meta-analyses.

As I explain in the paper, a meta-analysis of studies on moral judgment finds no impact of incidental disgust. Then, separately, a meta-analysis of studies on epistemic intuitions finds no effect of order.

A central claim of my paper is that we shouldn’t just be considering each of these effects separately. There seems to be something more general going on here whereby all of these seemingly different effects are meeting with the same fate.

I am intrigued by your idea of somehow doing a meta-analysis of this larger phenomenon. So far, there hasn’t been anything like that (just separate meta-analyses of the separate effects), but that is definitely an interesting idea.

(Also, I just wanted to mention that this research shouldn’t be taken to undermine situationism in moral psychology. All of these studies are about people’s philosophical intuitions, rather than their actual moral behavior.)

Thanks for writing!

Hi Joshua,

This comment asks you to in some respects think beyond the obvious scope of your post and the comments made thus far. I believe that the way that experimental philosophy has examined disgust decontextualizes and depoliticizes it, as if disgust is universally and indiscriminately experienced and distributed. But we might instead ask: Does everyone experience disgust in the same way? Are people equally subjected to it? Equally the subjects and objects of it? What forms of social power influence the production of disgust?

In fact, I think that this sort of depoliticized and decontextualized misrepresentation of disgust can be associated with how most philosophers study it. At the Pacific APA in 2019, for example, a panel on disgust took place during which several philosophers attempted to discern and clarify what exactly disgust is, whether disgust is an emotion, its relation to cognition, to intention, and so on. A few mentions were made of excrement, vomit, bad odours, etc.: What does it mean to respond to excrement or vomit in this way? When we feel disgust at the sight of excrement, are we experiencing an emotion devoid of cognitive content? Is disgust an evolutionary development?

In other words, all the presentations universalized, decontextualized, and depoliticized disgust in the same way that experimental philosophy and experimental philosophers seem to do. That is, none of the presentations addressed the fact that members of some social groups (but not others) are regarded as the embodiment of disgust, are perceived as essentially disgusting, and are thus subjected to and the subjects of (among other things) social ostracism and social annihilation.

How many new parents would describe their newborn’s soiled diaper as “disgusting” and be revolted by it to the point that they deem the infant worthy of disregard? Probably few, although many might experience removing the diaper as unpleasant. By contrast, how many upstanding people would describe as “disgusting” the homeless person who soiled their pants (because they are increasingly denied access to public washrooms)? How many socially privileged North American adults put their elders or younger disabled family members in nursing homes because it would be “too disgusting” to change their briefs and bathe them? And how and to what extent is the latter social production of disgust a prelude to the elimination of disabled people and seniors through medically assisted suicide and euthanasia?

Is disgust—that is, who is the frequent object of it, who has the unacknowledged privilege to invoke it, who is subjected to it, and why—relative to social situation and circumstances, social location, status, age, disability, race, gender, and so on? I think that it is.

Indeed, I think that an inquiry into disgust which takes account of its social and political constitution is another way in which to address the relativity, instability, and contingent character of moral intuitions about it.

It seems to me that the “what is disgust” and “how do people and cultures utilize disgust for norm enforcement” are separable questions (that is…unless you think they aren’t). Even constructivists about emotion can separate the “what is x?” from “how is x used?” question. You are surely right, Shelley, that disgust is used to enforce noxious (racist, ableist, sexist, etc) norms on many occasions and that this should lead us to think carefully about an ethics of disgust (or shame, or guilt, or anger, etc etc etc).

Hi Shelley and Caligula’s Goat,

Really glad that you are bringing up these issues. In my view, we should be thinking more about precisely this aspect of disgust and a lot less about the purported phenomena that have played such a large role in the existing literature.

In the paper, I distinguish two different ways in which people‘s moral judgments could be distorted by disgust.

The first is that people’s moral judgments might be distorted by a disgust they feel toward members of marginalized groups. This sort of distortion could be relatively stable across situations.

The second is that people’s moral judgments could be distorted by a disgust they experience as a result of factors in their immediate situation. (For example, even when judging someone who is not a member of a marginalized group, their moral judgments could be distorted by a disgust they experience because of a bad smell in the room.) This second sort of distortion would involve instability across situations.

In my view, the first phenomenon is a very important issue which we should absolutely continue to explore in further depth. By contrast, a growing body of evidence suggests that the second phenomenon does not actually exist. Thus, when it comes to the second phenomenon, the important philosophical question is the one about the philosophical implications of all the studies showing that people‘s judgments are remarkably *unaffected* by disgusting things in their immediate environment.

HI Joshua, you say: “that the tensions in people’s intuitions are themselves stable.”

I assume that moral intuitions are produced by System 1 processes, not System 2 processes. So, my thought is that two different System 1 processes are producing two different intuitions and both intuitions are stable, thus, the tension is stable.

Cheers, Graham