Next Year’s “Extra Brutal” Philosophy Job Market: Alternatives & Short-Term Opportunities?

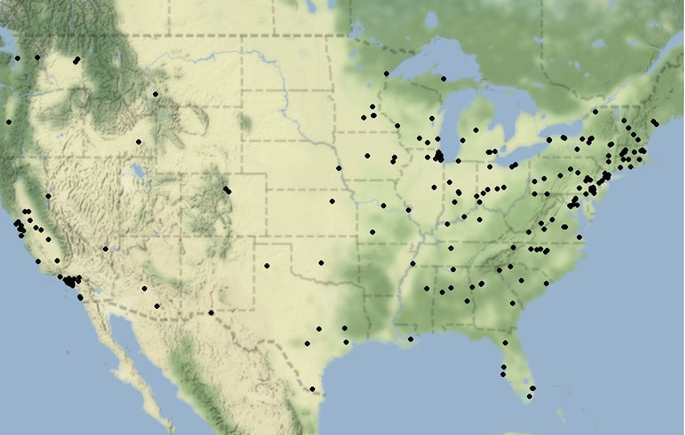

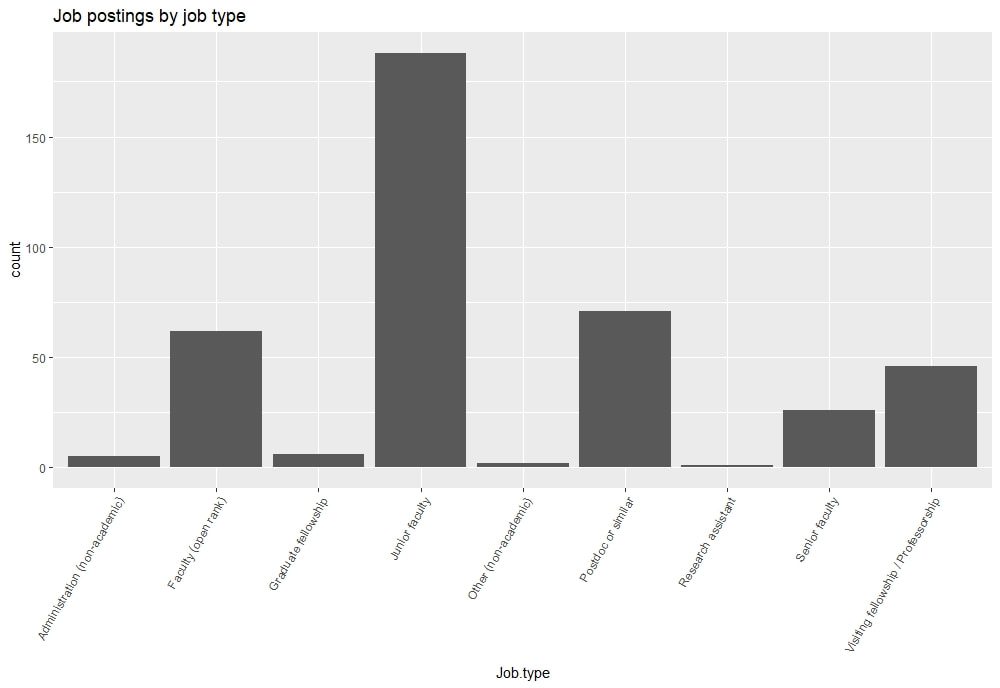

Between August 1, 2018 and July 31, 2019, there were approximately 180 junior jobs, 70 postdocs, and 60 open-rank positions in academic philosophy in the United States advertised.

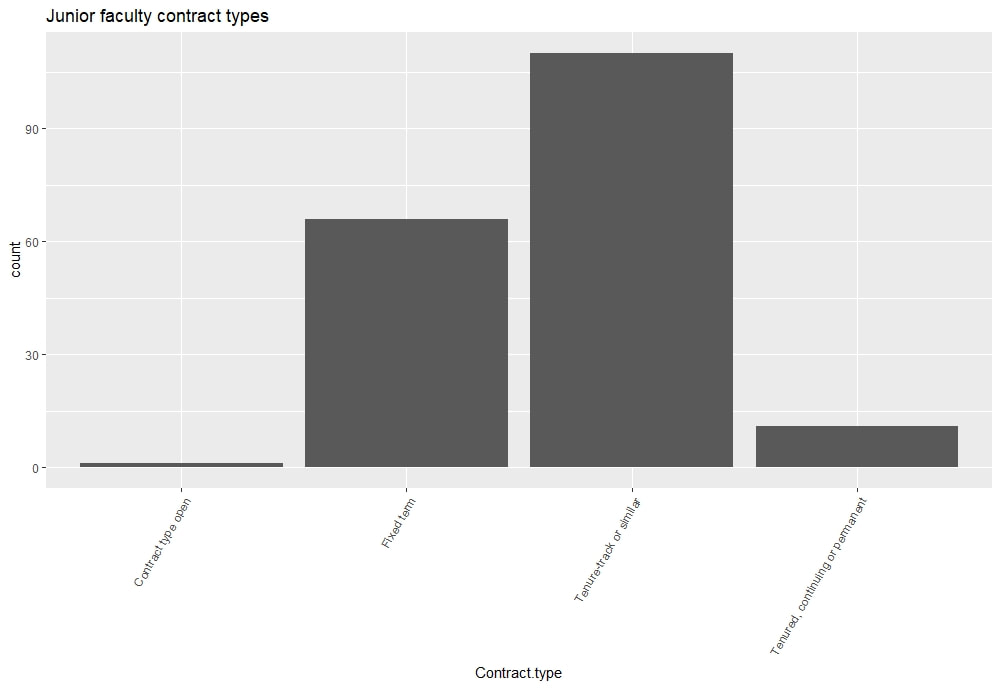

That data was compiled by Charles Lassiter, associate professor of philosophy at Gonzaga University, and is from a post at his blog. He takes a closer look at the junior positions and notes that about a third of them are not tenure-track:

Dr. Lassiter then looks at where there jobs are:

Academic philosophy jobs (junior, post-doc, open rank) in the U.S. during the 2018-19 job market (data collected and image created by Charles Lassiter)

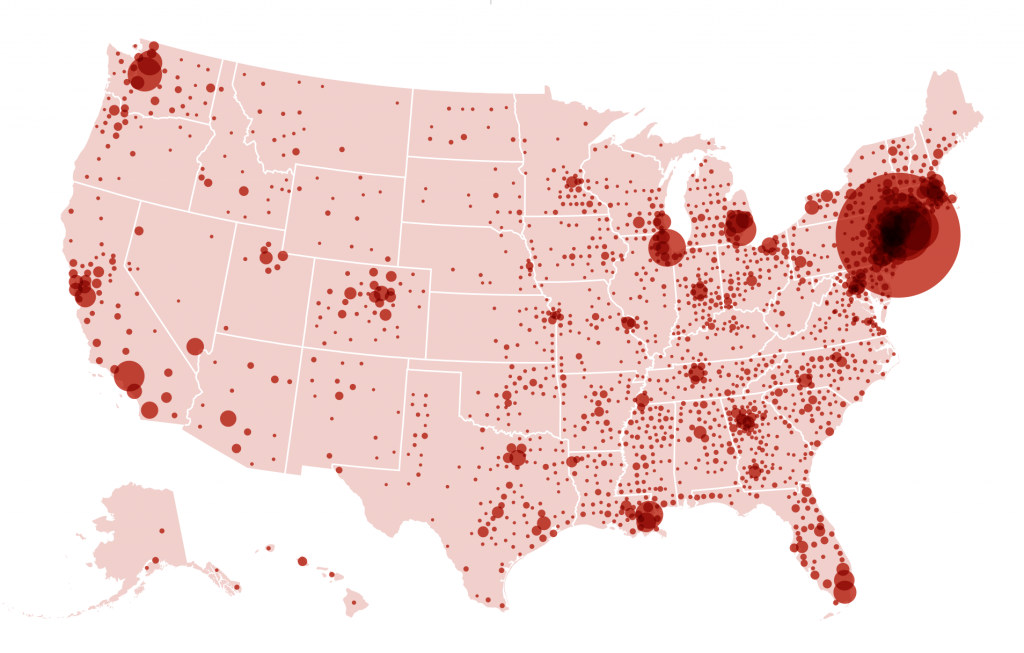

There are likely going to be much fewer dots on the 2020-2021 version of that map, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. Here is a map, last updated earlier today and published in The Guardian, showing the distribution of COVID-19 cases in the United States:

And here is a crowdsourced list, collected by Karen Kelsky (of the academic career consultancy The Professor Is In), of schools that have announced hiring freezes or pauses (here’s a Google spreadsheet of that list). Given how it is being created, I am not sure how reliable it is. But there is no doubt that, given the turmoil caused by the pandemic to universities, not to mention the costs (89% of university presidents surveyed about COVID19 are somewhat or very concerned about the “overall financial stability” of their schools, according to Inside Higher Ed), there will be susbstantially less hiring going on in the near future.

At the same time, while the pandemic has (and will continue to) delay some academic work and deter some moves, dissertation defenses are proceeding (virtually) and there is not likely to be much of a reduction in the number of job candidates. If the financial troubles of some universities lead them to cancel current searches or let go of faculty (non tenure-track faculty are especially vulnerable here), that could add to the number of job candidates.

What to do?

One reader (a tenure-track professor at a liberal arts college), concerned about “how extra-brutal the market is going to be”, suggested a post which solicits

(a) suggestions for short-term alternatives to the academic job market for fresh philosophy Ph.D.’s. and

(b) ways by which more institutions and senior philosophers might create such short-term options.

As an example of the former, there’s the Presidential Management Fellows Program, first brought to my attention by Shane Wilkins, and which several philosophers have taken part in.

As an example of the latter, the professor who wrote in recently learned that their school has a fund for its alumni to create post-doc positions, including in philosophy. Universities and their associated foundations may have other little-known options like this—maybe yours does—but it may require some investigative work to find out. It would be helpful, though, to hear about the various types of such opportunities so those who are asking around have a better sense of what to ask around for. So please share what you know.

I strongly encourage newly minted PhDs to explore the start up market, especially in technology in general and education technology in particular. (As you might have surmised, these sectors are more protected from the economic effects of COVID-19 than most other sectors). A great place to start is https://angel.co/. (You’ll get a lot more hits there than you will on LinkedIn.)

No matter how much you love philosophy, now is a good time to consider other opportunities. Just when you thought the academic job market couldn’t get worse, another seismic shift is coming for academia. Don’t despair, but be prepared.

Based on my experiences at a small ed tech start-up, the advise on offer here is pretty solid: https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/02/17/working-start-lets-you-use-your-phd-skills-different-genre-opinion.

With all due respect, I think that recommending that *all* new PhDs look into working at a start-up isn’t great advice. This isn’t to say that it isn’t the right option for anyone, but that working in the start-up world requires a certain mindset and willingness to live a certain kind of lifestyle that I think many PhDs will not be willing to engage in.

I worked in tech before grad school. One thing to keep in mind is that most start-ups fail. Now, this isn’t to say that if the company you’re working for fails, that you won’t have developed some valuable skills that you can take to another job. However, in terms of having a stable career path, working in a start-up is generally not going to be the way to go.

Start-ups are also often run by very young people without much (or any) experience managing people/managing money/managing expectations/etc.

If you’ve finished your PhD, you’re still quite young and largely unconcerned about these sorts of issues, then go for it. Otherwise, I’d recommend you look elsewhere for a good alt-ac career.

Point taken, Kent. While I didn’t say that *all* recent PhDs should look into start-ups, I do think it’s a great starting point for many recent grads without non-academic work experience. I’d argue that start-ups are attractive to grad students for the same reason that they tend to fail: start-ups take significant risks at many different levels, including hiring. With my “non-traditional” background, I received far more attention from start-ups than from other employers. And, in my current position, I have far more time to learn and develop than I would in a larger company with a more rigidly defined role, which is crucial at my current career stage. But I do agree that working in a start-up requires a mindset that not all grad students share.

I like the irony of there being an ad for a PhD program at the bottom of this post.

In light of the March 25th post, perhaps students could do ethics consulting work for government organizations, healthcare systems, and NGOs in the midst of Covid-19 (especially students who work in ethics, political philosophy, or philosophy of law).

Some of these organizations might even partner with ACLS so that you could get an ACLS/Mellon fellowship to do so: https://www.acls.org/programs/publicfellows/

[Relevant xkcd](https://xkcd.com/1138/) for those two maps.

I’m glad people are commenting with non-academic options, but I’m worried that given how gaps of employment or affiliation are generally frowned upon by hiring departments, without some sort of academic continuity through this period, we will have an entire cohort or two of talented philosophers who are effectively shut out of academia purely because of external circumstances that hiring departments are biased against or unwilling to take account of. Some employment, even if non-academic, is better than no employment. But I take it that the point is to give departments ideas about how to keep late-stage PhDs in the academic game while we ride out this cycle, without forcing them out of academia or giving hiring departments reasons to exclude them from the process.

So much of the conversation about how the pandemic is impacting universities has been about extending tenure timelines, moving to online instruction, or catastrophizing guesses about the next job market cycle. Solving the particular problem in this post requires a larger conversation about the status of graduate students through this crisis. This is a conversation that we are not yet having, perhaps unsurprisingly, since graduate students and other contingent members of academia tend to fall to the bottom of the list of priorities. Regardless, there are rumours of graduate students at some universities calling for extended funding timelines. Perhaps this can mitigate the increase in applications if future hiring departments can also be incentivized somehow to take account of the impact this time has had on academic continuity for folks who are unfortunate enough to be graduating into this market.

While I think it’s noble (or at least humane) not to tell newly minted PhDs to fend for themselves, I wonder whether “keeping late-stage PhDs in the academic game while we ride out this cycle” will simply delay the inevitable for the vast majority of grad students. At a certain point, we may need to come to terms with the fact that graduate education is broken beyond repair. I’m thinking of the current crisis as less of a cycle and more of an accelerant. If I’m right about this—and I think the projections are grim enough to lend at least some credence to my view—then keeping graduate students afloat might not be the best decision for grad students. It wasn’t right for me, in any event.

The graduate system is broken from the point of view of those seeking a job in academia.

It’s not broken from the point of view of universities seeking softer hiring conditions, i.e. more qualified candidates per employed post, with concomitant reductions in wages and working conditions.

For that reason, I don’t think that making the system any more broken from jobseekers is going to accelerate radical changes. In fact, in the long term, it’s in cash-strapped universities’ incentives to respond by “breaking” the system even more, by hiring more paying graduate students to increase short-term revenues and decrease long-term wages/conditions.

Postdoc9’s comments seem right to me, though I didn’t take Samuel Kampa to be suggesting that this would accelerate positive changes (or really any changes): I thought the claim was that this was accelerant in the sense of making the dumpster fire of the academic job market burn hotter.

In any case, it *should* make folks who are safe on the tenure track work harder to find help for grad students and recent grads (and everyone else not on the tenure track). But I seriously doubt it will. Generically (though not universally), they don’t seem to care, and more importantly, it is also in their interests to continue the current system. I think if we want to stay in this profession, and have decent wages and healthcare, folks working in NTT jobs need to unionize, and the unions need to work together across institutions for some kind of general strike. That would at least be a start.

Points well taken, postdoc9 and postdoc10. And yes, my sentiment was more in line with postdoc10’s interpretation.

I would only add that, as universities hire fewer and fewer faculty in general (not just TT faculty), collective bargaining could become that much harder to pull off. It would take a large, coordinated effort among highly job-insecure people who, relative to their private sector counterparts, aren’t accustomed to working as a team.

(I think it’s fair to say that department members rarely share common goals. To a certain extent, career advancement in philosophy is a zero sum game. You’re most likely to win when those nearest to you lose, at least early on in your academic career.)

FWIW, leaving pro philosophy was a deliberate but very difficult decision for me….*at the time*. To anyone who thinks they *might possibly* be happier outside of academia, I strongly recommend leaving. It’s easily one of the best decisions I’ve ever made—and I loved my department, my mentor, my cohort, and the work I was doing. To those who have lost their love of philosophy, leaving is a no-brainer, barring special circumstances.

PSA over.

That interpretation makes sense to me. I am staying in academia because things are going well for me and because I really enjoy it. Even then, it is relieving to know that I have had work outside of academia that I enjoyed. At least part of the supply-side glut is because there are a lot of people who believe that they HAVE to be in academia to be happy, but as far as I know, this is never actually true.

I agree completely. When someone feels like they *need* to keep grinding despite being terribly unhappy, that gives me pause. But I know people who have managed to do philosophy while developing a healthy detachment from the din of academia, playing the job market in consecutive years without being crippled by anxiety. More power to them! I’m genuinely happy to have cleared the way for those happy few.

I agree with all of these comments.

Of course it will delay the inevitable for the vast majority of grad students—most people already don’t get jobs after trying for several years in a row, but that’s not a reason to not give students in this circumstance an option to have a fair chance. Sure, most of them won’t get jobs, but some of them eventually might. It shouldn’t be up to the institution to call that shot—it should be up to the student. Institutions should *within reason* support their students through this, and that’s not to say anything about whether they actually will.

Just because it wasn’t right for you doesn’t mean the same is true for everyone, nor do the chances make it the case that everyone should immediately jump ship only to try entering other economies that are no less broken at this time.

“Just because it wasn’t right for you doesn’t mean the same is true for everyone…”. I completely agree, and none of this is a knock on PhD students / postdocs / adjuncts who are sticking it out or faculty who are compassionate enough to lobby for additional funding for their students. But I do think leaving the field is right for more people than your average academic realizes. *I* didn’t have a concept of how right my decision was until I left; my “getting it right” was quite accidental. People don’t know what they don’t know, I guess.

Giving students a life vest for a year or two is great, of course, but I think it’s misguided (if well intentioned) to encourage all (or even most) aspiring faculty members to wait out the cycle. We’ve been told to “wait it out” for a long time, and the promissory note is feeling increasingly empty. When semesters become years and years become decades, the cynicism and lost wages multiply. That doesn’t happen to everyone, of course, but it’s common enough that, at the very least, we shouldn’t take a first year grad student at their word when they say “I know I want to pursue a TT position in philosophy”. People don’t always know what they want.

On the economic side, I am without a doubt more stable now than I was a year ago, and I’m more stable than I would have been as a postdoc. I’m lucky enough to be in a sector that hasn’t been hit very hard by this crisis, but I’ve also had the opportunity to develop skills that would allow me to rebound if, say, everyone suddenly lost their jobs and the economy picked up again in a year. That, I think, is the major difference between academia and many other sectors of the economy: each position in academia is fragile, and if you lose it, you might be out for good (or indefinitely stuck in the academic underclass). Various private sector positions can be fragile, for sure, but losing one job doesn’t mean you’re out of the game. That’s not true for all positions, of course, but I’d venture to say that, in general, it’s truer for non-academics than it is for academics.

We have seen a break in tenured positions after the 2006/7 recession and there will be an even bigger wave of turning tenure positions into non-tenure, short-term and adjunct positions, so I hope we do not give people and institutions even more reasons to give out not-well-paid short-term jobs in academia.

As someone who works in a school that already does a lot of on-line ed, I can say that I expect the move to doing more of that during the crisis is going to push the use of adjuncts of significantly.

Thanks Charlie for this great info!

Also, if anybody is interested in learning more about the PMF program, let me know. It’s a great opportunity to advance your career and make a positive impact in the world. To qualify you need to be a recent graduate degree earner in some field (i.e. about to finish or have finished in the last 2 years), you must to be a US citizen or national; and if you are male you mist have registered for selective service, i.e “The Draft”.

If you meet those qualifications and would like to know more, please reach out to me. I’m happy to talk!

This problem has been upon us for some time, and it’s about to get even worse. We just don’t have anywhere near enough tenure-track at existing institutions for those who will need them. It’s too late for us to ensure that there are jobs waiting for everyone who completes a PhD. But we can still *flatten the curve* by following some simple practices that make the situation better for everyone.

True, some fortunate ones will face the terrors of the job market and recover. But some members of this population will fare much worse than others. Particularly vulnerable are graduate programs with poor or nonexistent placement rates. Such programs don’t just harm the students they admit: they also harm everyone else on the job market by overloading the capacities of search committees to give due attention to each candidate, and they significantly weaken the power of the faculty in bargaining by creating a nightmarish hirers’ market. Yes, shutting down or limiting graduate programs with poor placement records means doing without cheap and easily exploitable TA labor, and it means that some faculty will not be able to fulfill their dreams of supervising graduate students. But reining in the epidemic affecting job searches and the lifelong damage it causes must take precedence. We need to *practice social distancing* by doing our part to thin out the overcrowded job market.

A philosophy major is a wonderful preparation for all sorts of careers. One source of the trouble is that many undergraduate instructors irresponsibly encourage their students to pursue graduate work, feeding the epidemic. Many of these graduating majors could have perfectly fulfilling lives, and continue to enjoy philosophy non-professionally, if only they would *stay at home* rather than start the process of moving around the country or the world pursuing graduate studies, untenured labor, and so on, adding to the pressure on the system. We need to *stop the spread* of the view that graduate school in philosophy is viable under our current, overcrowded conditions.

We can’t prevent the ravages of the job market on everyone wrapped in it now. It will be difficult to do much to help the people about to face it over the next few years. But if we are prepared to rein in our ambitions and *prevent an overload of the system* at long last, we can beat this thing together within a few years. Unfortunately, we will have to do so despite the complete inaction and seeming obliviousness of the leadership of our national organization on the matter. But this is too big a problem for us all to ignore.

It’s worth remembering that it’s as a result of the 2008/09 crash that graduate students now absolutely need to have publications in hand when they apply for jobs. It may have been a while in the offing, but ’08/’09 rapidly accelerated and cemented it.

I don’t know how much more serious the arms race can get, but I expect it to amp up.

A natural next step is that graduate students must win at least $1,000 of funding for other members of their school before being considered as a serious job candidate.

In Europe, the UK, and Australia, experience in getting grant funding is already a desired, and sometimes a required, feature of getting a “permanent” job in philosophy and related areas. I would be sad, but not surprised, to see this come to the US.

At my university in Asia, tenure and promotion is impossible without receiving external grants – for faculty throughout the university.

This 30 month research post in social epistemology may help.

https://www.philjobs.org/job/show/15266

Last year I bailed on my five-year academic job search, learned some javascript, and got a job as a software engineer. If you are underemployed or about to be underemployed in philosophy, you should consider making the switch to software engineering, where you can make a whole lot more money, have a whole lot more geographic flexibility, and enjoy your job all the same. Check out the jobs outlook for software engineers here: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/computer-and-information-technology/software-developers.htm

How did you go about learning javascript? Asking for a friend who is token identical with me.

There are a few good resources out there (and many no so good). I myself learned by reading the MDN docs and tutorials (https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript). I followed that up with Hack Reactor’s free prep program (https://www.hackreactor.com/prep-programs). Another good option is freecodecamp.org. If you’re more the learn-by-watching type, I recommend anything on Udemy by Colt Steele and anything offered at codewithmosh.com. Mosh’s courses are a bit more advanced, so you might start with the free resources before taking them.

Just knowing javascript probably won’t get you a job. If you are serious about making the switch, I’d recommend using the above resources to learn: html, css, javascript, React, SQL, Node.js, and Express.js, most of which is just javascript anyway. Then build something.

If you consider doing a bootcamp, make sure you look into audited placement data (https://cirr.org). Not all bootcamps are equal. I would absolutely not pay for a bootcamp that does not publish third-party audited placement data. Those that do publish audited data tend to be more expensive, but the ROI can certainly work out. I know several bootcamp graduates who graduated into $100K+ jobs.

Just to add that Caleb Ontiveros has a very supportive Facebook group, “Philosophers in Software Engineering,” where you’ll find (and can solicit) further advice. Also, another field to look at is data science, particularly for people who have quant skills from work they might already have done academically.

Don’t think about learning a specific language. Learn how to program. If you understand the abstract ideas, learning a new language is fairly simple. (Assuming you’re good at abstraction – but that’s philosophers’ key advantage.)

And how (where) does one go about doing that?

I don’t know if anyone is reading this thread anymore, but I would suggest taking a look at MIT’s 6.0001 and 6.0002. It’s a two part course, both together covers one semester. The whole course is online, with lectures and psets. The lectures are great, and the book used is great. Watch the lectures and read the book along with them, and by the end you’ll be fairly well off with python. But a lot of the material is language independent. From there you can pretty easily pick up most languages. Here’s the first part: https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/electrical-engineering-and-computer-science/6-0001-introduction-to-computer-science-and-programming-in-python-fall-2016/

I think there’s little doubt that this crisis will aggravate an already terrible job market for PhDs, humanities PhDs likely in particular. But I’m just not sure that the underlying fundamentals are any different; they’re just becoming easier and easier to see.

One issue is broadly cultural. Academic hiring–maybe especially in philosophy? I’m not sure–has a very peculiar set of shibboleths that persist largely unexamined. For example, as a poster above mentioned, one is that hiring committees frown upon candidates whose records show ‘gaps of affiliation’.

A marginally charitable reading of this custom might say that these candidates are frowned upon because appear ‘unserious’. But what if a candidate chooses to leave academia temporarily to pursue experiences that make her a more well-founded philosopher, such as pursuing a deeply held artistic talent, or taking a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to travel somewhere that will give her incredible perspective?

Some of us would insist that /this/ would be an exception. And they would be right–people who are well-rounded and multi-talented are more likely to be insightful philosophers.

But how do we square this with the oft-heard advice that “it’s best to wait until you have to tenure to explore your personal interests”, that on your professional website you should be sure “only briefly to mention” other serious interests and hobbies on the “about me” page, lest hiring committees fear you will not spend virtually all of your labouring hours on your research program, that hiring committees want “known quantities” and “predictability”.

Putting aside the obvious fallacy that having serious interests outside of academia has no bearing whatsoever on whether one is a “risky candidate,” this myopia is seen as obviously silly when you realize that shibboleths like these are not embraced in many other professions–yes, even ones that are ‘high-achieving’. Contrary to public opinion academia is a exceedingly timid and conservative institution, and it strangles itself as a result.

I work alongside engineers now. And it’s helped me learn some very valuable lessons. One is that there are a shit tonne of exceptionally bright people outside of academia, and yes, outside philosophy, too. Another is that there are a lot of quirky, strange, talented people who find incredible success working in challenging, exciting fields that do not insist on the cardboard-conformity that strangles so much academic hiring.

So I think there is little reason to despair. Leaving philosophy does not mean that you’ll be forced to suffer idiots. To the contrary, if you’re lucky it means you’ll be forced to realize that academia is not necessarily the preserve of society’s best and brightest. And to boot, there are many people who will think your quirky pursuits and talents make your analytical skills cooler rather than the opposite.

(Well, clearly I had to get something off my chest. I hope this gives anyone reading a bit of hope.)

Thank you for your comments! A few things in response:

1.

There are at least a few professions outside philosophy that look down on candidates who have “gaps of affiliation”. Investment banking and consulting, for example, have entry level hiring processes that exclude anyone who is not currently a junior or senior at a target school. If you take two years off to go do photography in Thailand, you can still apply in other ways but are cut off from these specific recruiting channels and your application will almost certainly not be considered unless you have someone inside advocating for you.

Secondly, ageism is rampant in corporate America. Taking time to do something else necessarily makes you older. You will be more likely to appear as though you would demand a reasonable wage, that you are inferior to people in your age cohort who have more experience in whatever profession it is, and that you will be more difficult to brainwash into accepting and perpetuating abusive corporate cultures with no work-life balance, etc.

2.

I think the reason hiring committees denigrate candidates with experience outside academia is mostly due to this being a legal way to narrow down the several hundred applicants to a more manageable number in order to save them work. It also serves the secondary function of expressing and reinforcing many professors’ desire to believe that they deserve the position they have in the face of so many qualified applicants (unlike these dilettantes, I have worked hard, have always been very committed to the profession, etc).

3.

In my experience having left academia for 3.5 years now, I have found no shortage of very intelligent people to talk with, but the range of acceptable conversations is much more narrow than it was in grad school. It has definitely been a struggle to find people in professional settings with significant knowledge and interest in culture and the humanities.

Kinda surprising grantwriting didn’t make the first 30 posts? All in, probably easier to cover your salary by writing grants (including for philosophy projects) than to get a tenure-track job. Say a tt job has, at best, a 1% acceptance rate and NSF, Templeton, etc. are 10% (or 20%, depending on stream). Also if you “bring salary”, it’s a lot easier to start conversations with departments (e.g., hire me at .5 fte, I’ve got funding for the other .5). Because this stuff isn’t “advertised” it’s invisible in certain ways, but it’s definitely there—and likely soft funding will underwrite more positions moving forward, particularly for bioethicists working in medical schools, but probably more generally as well.

I left academia for tech, and I’ve been enjoying it quite a bit. If anyone wants to talk about what that transition looks like, feel free to email me: [email protected].

I like talking to folks about career stuff, and have a special fondness for talking to academics about careers in tech.

It is sometimes more difficult in universities to hire to a new temporary position, like a new postdoc, than to extend one that already exists. In light of the looming ‘extra brutal’ job market next year, I would urge faculty to consider the possibility of extending postdocs or teaching fellowships, if they would otherwise expire next year—for the sake of the postholder if not for other reasons. That is what our department will be trying to do.

To what extent people think this pandemic will affect graduate admissions next cycle? Is there a possibility that some schools might not be taking any new candidates at all (or even if they would, the cohort sizes would be significantly smaller)?

The possibility is definitely there. Some programs cannot afford to extend timelines and funding for their current graduate students without shrinking their incoming cohort. Whether any of the schools you’re interested in are likely to do this is a different question. I would be most worried about state universities in states with Republican legislatures, slightly less worried but still quite worried about state universities in states with Democratic legislatures, somewhat worried about less-known private universities (though most of the ones in financial danger don’t have grad programs), and almost totally unconcerned about big-name private schools like the Ivies Not that they won’t have budget pressures, but their ability to fundraise ludicrously outstrips the others.

Thank you! In your opinion, does it still make sense to continue investing a significant amount of time and energy into my grad school applications? To give you some context, I am a college junior about to apply next cycle and I was going to do a full-time, faculty-mentored research project this summer that will most probably turn out to be my writing sample. Next semester, I will be filling my schedule entirely with several upper-level philosophy courses. Should I not have done this? Should I have opted for more pragmatic academic and professional choices – choices that will land me a job upon graduation in this economy? To be clear, I’d pick philosophy academia over a professional career in other fields any day, but if grad schools won’t even accept any new candidates, to begin with, my prospects in academia are a nonstarter. In short, then, should I give up my hopes for grad school and start looking for something else?

P.S. My list of schools is a mix of Ivies, state schools in both democratic and republican legislatures, private universities, and a decent number of MA programs. My AOI is ethics and moral philosophy so I’m mostly looking at the top to mid-tier schools in that area.

All the usual financial and prestige-based grounds for a graduate program remain. Even if some schools reduce their places next year because of immediate financial difficulties, others will not and those that do likely will not reduce the number to zero. Any reductions next year are unlikely to be permanent or long-lasting for all the reasons programs rarely reduce their numbers. If you are as set on an academic career as you say and if you are good enough to get into programs of a certain rank, you will be fine even if you must wait a year because you get squeezed out in the one year which potentially will have significantly fewer places. If things don’t work out, you can always choose one of those other career paths, which you say you value less than the philosophical one, at age 23 or 24 without losing anything important.

Take the mentored research project and enjoy it because it is a worthwhile experience, not merely for its instrumental benefits. Life is not to be lived as mere preparation for your next planned stage of it.

I am of the opinion that as things stand, even if philosophical academia is your absolute #1 preferred career choice, you should still not go to graduate school and pursue your #2 preference instead. (Unless your #2 preference is law school, in which case you should skip down to #3.) I could go on at length about my reasoning but won’t.

Pragmatically, if you can afford to apply next year there’s no harm in applying. Schools that aren’t going to admit or fund will say so. You could also take non-academic work for a year or two and apply when funding is no longer restricted. If you’re a compelling applicant next year, you’ll be a compelling applicant in two years, particularly if you have something to point to in your application statement that shows you’ve stayed active in philosophy. Attending a conference or two, for example, will actually be more open than normal, and you could easily sit in on a couple. Or you might find that non-academic work isn’t nearly so bad as you’d feared, and that livable wages are kind of nice, actually. Either way you’ll be fine.

Also, I completely second JDF’s final statement. “Life is not to be lived as mere preparation for your next planned stage of it” is very eloquently put. Do the project because it’s worth doing. You’ll learn useful skills anyway, but that’s not the point of it.