Philosophers: Consider Signing Amicus Brief on Insanity Defense

“Does a state’s abolition of the insanity defense comport with fundamental principles of justice and pluralist toleration?” That is the question taken up in an amicus curiae brief by Gideon Yaffe, professor of philosophy and law at Yale University, in regards to Kahler v. Kansas, a case the Supreme Court will be hearing.

In a message posted at Pea Soup by David Shoemaker (Tulane), Professor Yaffe writes:

I’m writing to ask for your signature on this amicus brief which concerns Kahler v. Kansas, a case that the Supreme Court recently agreed to hear. The state of Kansas abolished the insanity defense. Mr. Kahler, who is severely mentally ill, murdered his family and was convicted at trial after being barred from offering an insanity defense. The question is whether the Constitution requires a state to offer one.

I was asked by the Northwestern Supreme Court clinic to write a short amicus brief on behalf of philosophers arguing, as I believe, that basic principles of justice require that criminal defendants be given an opportunity to defend themselves through an insanity defense. I am hoping that you will agree to sign the brief. Law professors with significant background or interest in philosophy are also encouraged to sign.

Time is too short to revise the brief at this stage, unfortunately. It is intended as a consensus document, and so it is intended to abstract away from disagreements about the nature of moral or criminal responsibility, and about disagreements about what liberal toleration requires. My hope is that we can all agree that sanity is a precondition of criminal responsibility and that toleration does not require us to accept a state’s judgement to the contrary.

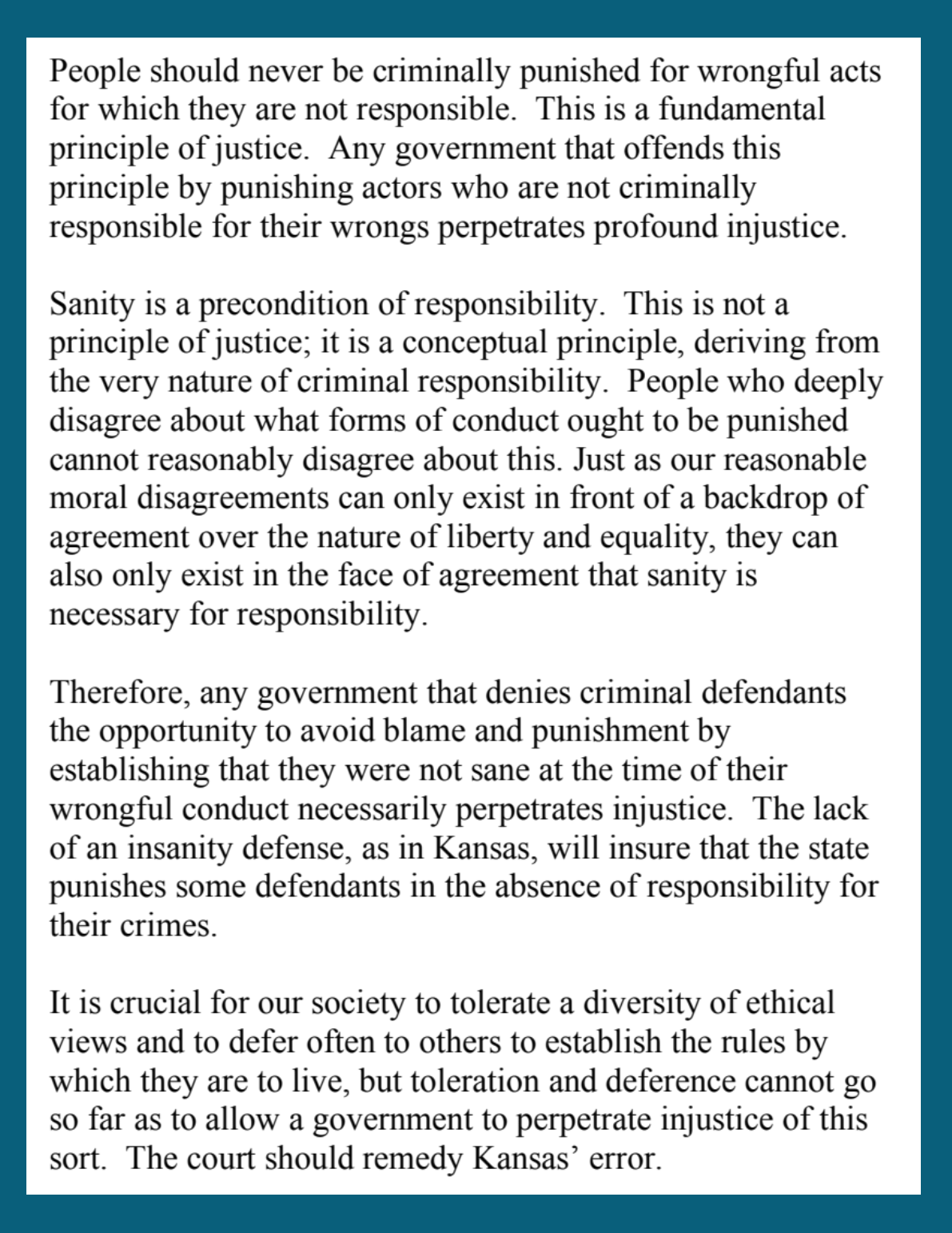

Here’s the summary of the argument in the brief:

You can read the entire brief here.

Professor Yaffe requests signatures before Friday, May 31st. He says:

If you are willing to sign, please reply or send a brief email to [email protected] expressing your willingness to sign and including two sentences describing yourself of the form “[Your Name] is [title] at [Your university]. She has published extensively about [e.g. moral responsibility and blame].”

I guess the question is why do we need an insanity defense, given a mens rea requirement? Some theorists, for example, think that the insanity defense is redundant because, if someone is legally insane, they might not hold the relevant mental state(s) enumerated in the statute. So you could easily agree with the premise (i.e., that principles of justice preclude us from convicting the insane) without agreeing with the conclusion (i.e., that we need an insanity defense to do so).

So I wonder what the argument is meant to be that contravening the mens rea requirement for criminal liability is *constitutionally inadequate*, as against a sui generis insanity defense. I don’t see where the amicus brief speaks to this, despite it being a pretty obvious and fundamental question. Just to be clear, I agree with everything else that is argued for (cf., the “summary of argument”, which is very clear); I just don’t see how it supports its intended conclusion.

Also, as a substantive point, note the Court’s holding in *Clark v. Arizona*; Arizona’s posture was even more restrictive than Kansas’, yet nevertheless cleared the Court. (Arizona barred even presenting evidence vis-a-vis mental health, whereas my suggestion above would allow the introduction of such evidence, just not into an insanity defense *per se*.) Given that holding, it’s hard to see why the Kansas posture would be unconstitutional, or at least as a first approximation (i.e., it’d take 50 pages to argue for and these notes aren’t meant to be dispositive).

I don’t think the Court in Clark v. Arizona affirmed a rule “barr[ing] even presenting evidence vis-a-vis mental health.” Rather, it affirmed a rule requiring that certain kinds of expert testimony regarding mental disease and mental capacity be presented in the context of an insanity defense.

On the more substantive point, I thought the brief was pretty clear. The thought (which seems reasonable to me) is that there may well be cases in which the defendant has the appropriate mens rea, but isn’t sane. For example, he or she might intend (or, whatever) the act and its consequences, without recognizing (because of insanity) that what he or she was going is wrong. In such a case, we might reasonably think that the defendant should (constitutionally) have an affirmative defense.

You might be right on *Clark*, here’s the relevant part:

“The case presents two questions: whether due process prohibits Arizona’s use of an insanity test stated solely in terms of the capacity to tell whether an act charged as a crime was right or wrong; and whether Arizona violates due process in restricting consideration of defense evidence of mental illness and incapacity to its bearing on a claim of insanity, thus eliminating its significance directly on the issue of the mental element of the crime charged (known in legal shorthand as the mens rea, or guilty mind). We hold that there is no violation of due process in either instance.”

On the other, some jurisdictions have thought that, for example, if a statute requires that the defendant KNOWINGLY committed some crime (or INTENTIONALLY, or whatever), AND IF the insanity was of such a nature that it could negate this requirement (e.g., X was insane such that he couldn’t knowingly do Y), then a sui generis insanity defense isn’t necessary. I take it your point could be that there are OTHER kinds of insanity that might NOT negate mens rea, and that this analysis wouldn’t capture the relevant feature of those. You could be right there, too, I’m not sure.

I guess I was just surprised the ACB didn’t even acknowledge the points/literatures/case law, but maybe they can be cabined as further afield. That said, I take pause on putting my signature to something if I don’t understand the details or feel convinced by the analysis, which is why I (respectfully) abstained on this one. I also wonder, dialectically, whether “please sign this by 400pm, before we can talk or think about it” has much going for it.

Apparently, signatures must be in by 4 today. So, hurry if interested.