Philosophical Artworks

Do you know of works of visual art that convey particular philosophical ideas, questions, problems, positions, or philosophers?

If so, find an image of it online and include it or a link to it in a comment with a sentence or two (or more if you’d like) explaining the philosophical connection. The connection to philosophy need not be intended by the artist, of course.

It would be great to have a sort of online philosophical art museum, no? Let’s get one going

(Advice: to keep your comment from getting held up, include just one link to an artwork per comment. If I have time, I’ll insert the image into your comment.)

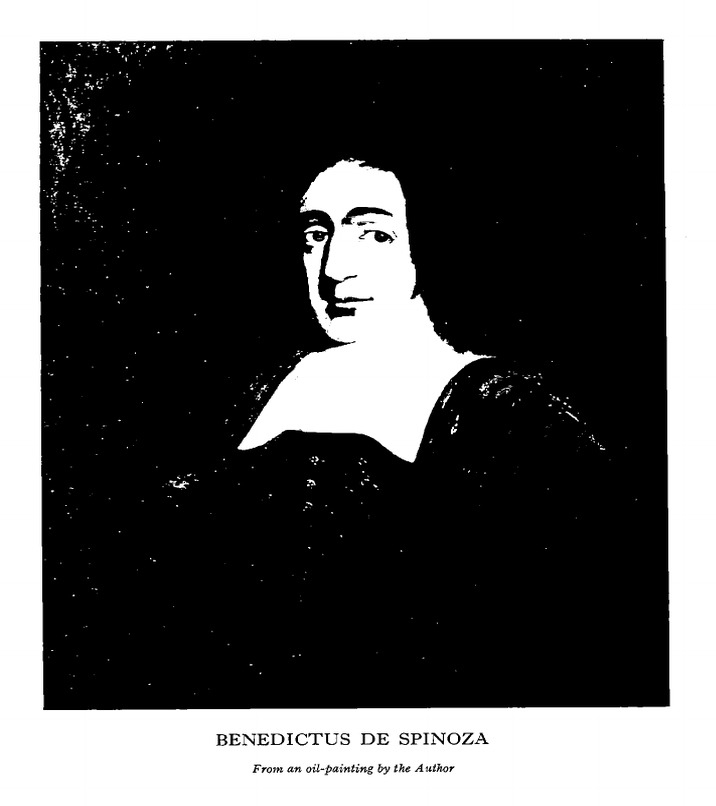

Way back when I was writing my dissertation on Spinoza, I admired H.F. Hallett’s portrait of that philosopher. Hallett wrote three books on Spinoza, I believe, but that must have seemed insufficient homage to him, since he also painted a portrait of his hero for the frontispiece of one of those books. Who could have put more devotion into a “philosophical” painting?

Some music by “Mahavishnu” John McLaughlin also comes to mind…but maybe that doesn’t count.

Let me know if that’s not the right image, Walter. As for music, let’s leave that for a subsequent post and stick to visual arts for this one.

No, but maybe that’s another one Hallett made for a later book. I was thinking of this one, for Aeternitas :

https://www.google.com/search?q=h.f+hallett+aeternitas+spinoza&rlz=1C1GCEA_enUS782US782&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj3nJ2QkrnhAhWjm-AKHUDnCNkQ_AUIDigB&biw=1137&bih=736#imgrc=Ut-awyBzJljPNM:

Sorry about the music reference. I missed the “visual” completely!

W

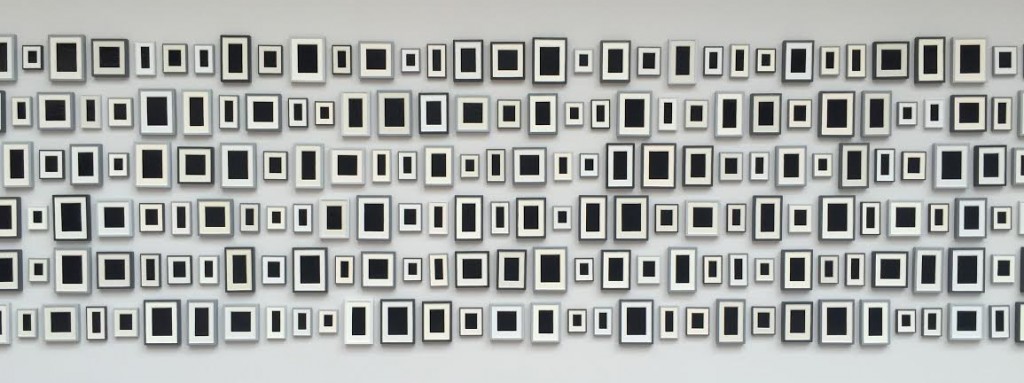

The work in the original post, “Collection of 480 Plaster Surrogates” by Allen McCollum invites questions about individuating objects and part-whole relations (mereology). Looking at it, one might ask how many works of art are on the wall? One? 480? Countless?

Making things a bit more interesting, each component of the piece is not a painting in a frame but a single piece of cast plaster that has been painted with no trace of brushwork to look like an empty frame with matting, intended to convey mass production.

Here’s a description from MoMA about a similar piece by McCollum.

“The work in the original post, “Collection of 480 Plaster Surrogates” by Allen McCollum invites questions about individuating objects and part-whole relations (mereology).”

True, but I still like it. My nomination is Fra Angelico’s “The Mocking of Christ”, shown here in its home at the San Marco convent.

http://www.artnet.com/artists/robert-polidori/the-mocking-of-christ-by-fra-angelico-cell-7-a-XAfscQLHo8VkR8QqottScQ2

Reminds me in a few ways of philosophical practice. It explicitly shows you, via the figures of Mary and St. Dominic, how to respond to the mocking, rather than saying “experience it however you want!”. Nor are these two figures in the midst of the event, experiencing it in its full richness. They’re attending to a stripped-down, idealized version of it, with the bits irrelevant for their purposes (i.e. the bodies and faces of the mockers) removed.

I’m sure Christian philosophers (among others) would have more insightful things to say about this weird, austere painting.

The question is whether there could be a work of visual art that did *not* pose some philosophical question, *nor* indicate any philosophical idea.

After Duchamp, any object is potentially a work of art. Many works pose and answer the question, what is art?, some in more interesting ways than others. Many so-called conceptual works are “about” (if that’s the right word) the significance of contexts, contents, or circumstances of various kinds, and so these are about semantics, as well as social and ethical questions about these contexts, contents, or circumstances. Many older works have religious topics, so these convey religious ideas, or could be taken to pose religious or theological questions. History paintings should trouble us with the question of in what sense these portray historical fact, and how there are such things as historical facts. Life drawings and still life should raise questions about norms of representational correctness. Nudes and other representations of human bodies pose ethical questions about how bodies are represented. And so on.

Suppose there were an artwork that did not pose any philosophical problem or convey any philosophical idea. Then it would indicate an idea of the absence all philosophical content – a subtle idea indeed!

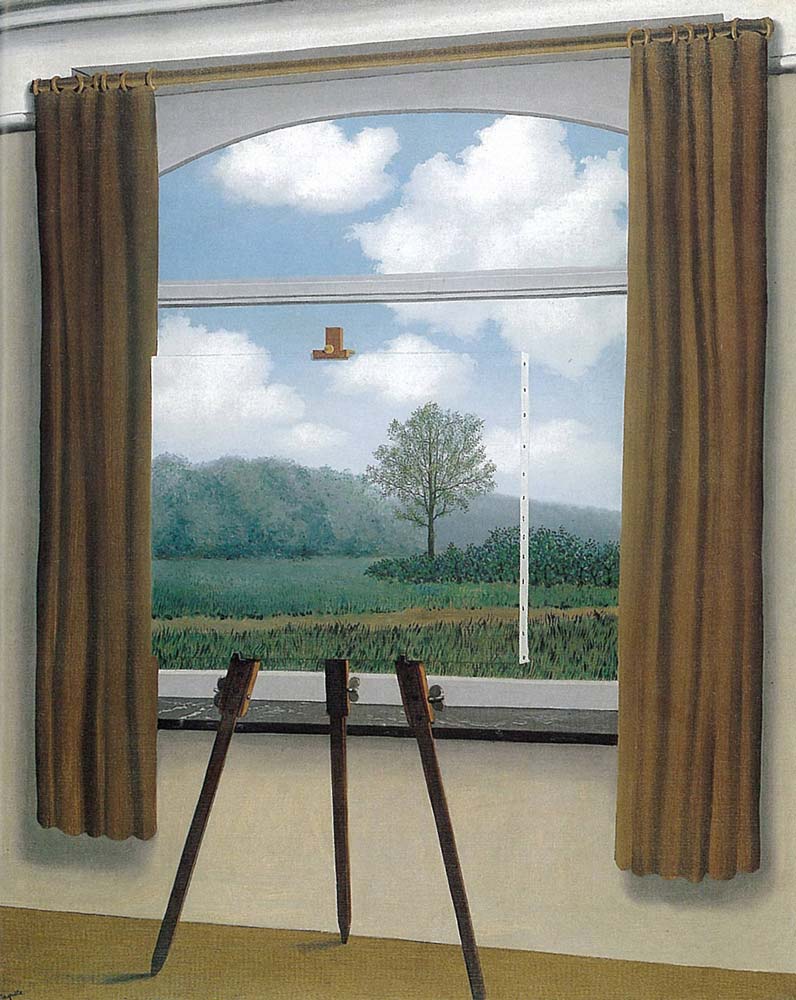

“The Human Condition” by René Magritte. http://totallyhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/The-human-condition-magritte.jpg

It raises questions about what perception is and more generally of what our experience of the world is.

I mean, more or less anything by Magritte is philosophically relevant. Though obviously this is a particularly good example.

I often appeal to the central image of Plato and Aristotle in Raphael’s “School of Athens” in explaining the difference between their metaphysics. Whether or not this was intended by Raphael, I take Plato’s upward pointed finger to be gesturing to the Forms and Aristotle’s outward extended arm to be gesturing to the world of sense. “Where are the real things?” I imagine to be the question they were both just asked, and they answer with their hands. “Up there!” says Plato. “No, down here!” says Aristotle. (This idea isn’t original to me, but I don’t know where I got it.)

I’ve always thought “Drawing Hands” by M.C. Escher (http://totallyhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Drawing_Hands.jpg) was a good representation of paradox (as is a lot of his other work), but it could also be interpreted as depicting a Wittgensteinian criticism of philosophy as working on problems it creates through its own misuse of language.

Might this not also represent a virtuous circle? As each hand is brought further into being through the other’s act of drawing, each can better bring the other into being by the act of drawing.

I believe it represents a reflexive domain! See Reflexivity and Eigenform: The Shape of Process.

Many of these are fairly obvious, but it might be good to list them anyways.

The “Four Sights” of Siddhartha Gautama are central episode for Buddhism and Buddhist ethics. It’s a fairly common motive for Buddhist relief sculptures. Here’s one example: http://www.ancientindia.co.uk/buddha/story/images/ps215269_1.jpg

The allegory of “veritas filia temporis”, truth as the daughter of time, articulates the idea of scientific progress in the Renaissance. It is captured, for example, in this beautiful print: https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=179955001&objectId=1622622&partId=1

Cezanne’s early still lives illustrate a problem in the philosophy of perception: If I see a round plate in an oblique perspective, do I see it as round, as elliptical, or as both

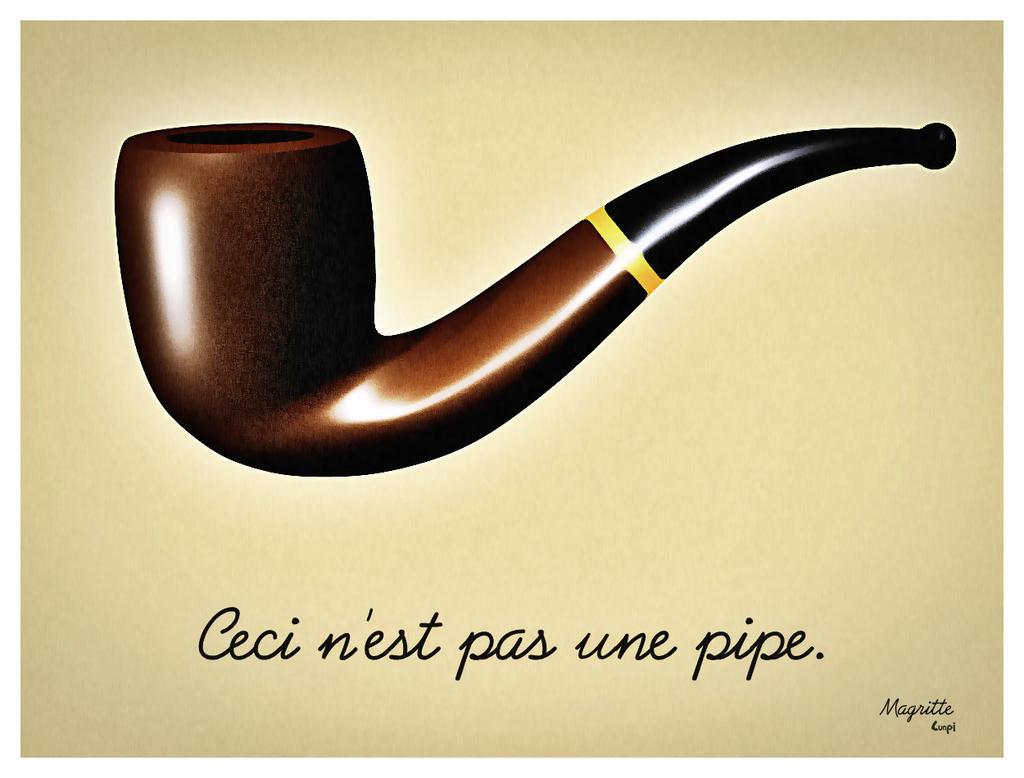

Magritte’s “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” directs our attention to the paradoxical nature of depiction and representation (cf. Merleau-Ponty): http://img08.deviantart.net/83d7/i/2008/229/8/f/ceci_n__est_pas_une_pipe_by_lunpi.jpg

Duchamp’s “Thirty are better than one” challenges us to articulate the notion of artistic or aesthetic value: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-nL6MfqwC0pU/TtD5WdLrc5I/AAAAAAAAAtE/D2DSAvj2Nic/s1600/thirty-are-better-than-one-1625.jpg

Lots of the works of Barbary Kruger illustrate issues in feminist and political philosophy. This one is especially philosophical, as it relates to the problem of other minds, which in the phenomenological tradition is often discussed through the concept of the “gaze” and the question who we can perceive another subject without them just being for us, i.e. without them not truly being a subject.

If you’ll forgive the pedantry, the actual title of the Magritte is “La trahison des images” (the treachery of images). ‘Ceci…’ is just an inscription. Donc: cela n’est pas un titre!

This one may be too literal, but it does show that artists are paying attention to philosophy! https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81435 Joseph Kosuth, One and three chairs. Great for Book X of Plato’s Republic.

Just today I saw One and Three Mirrors at the National Gallery in Canberra!

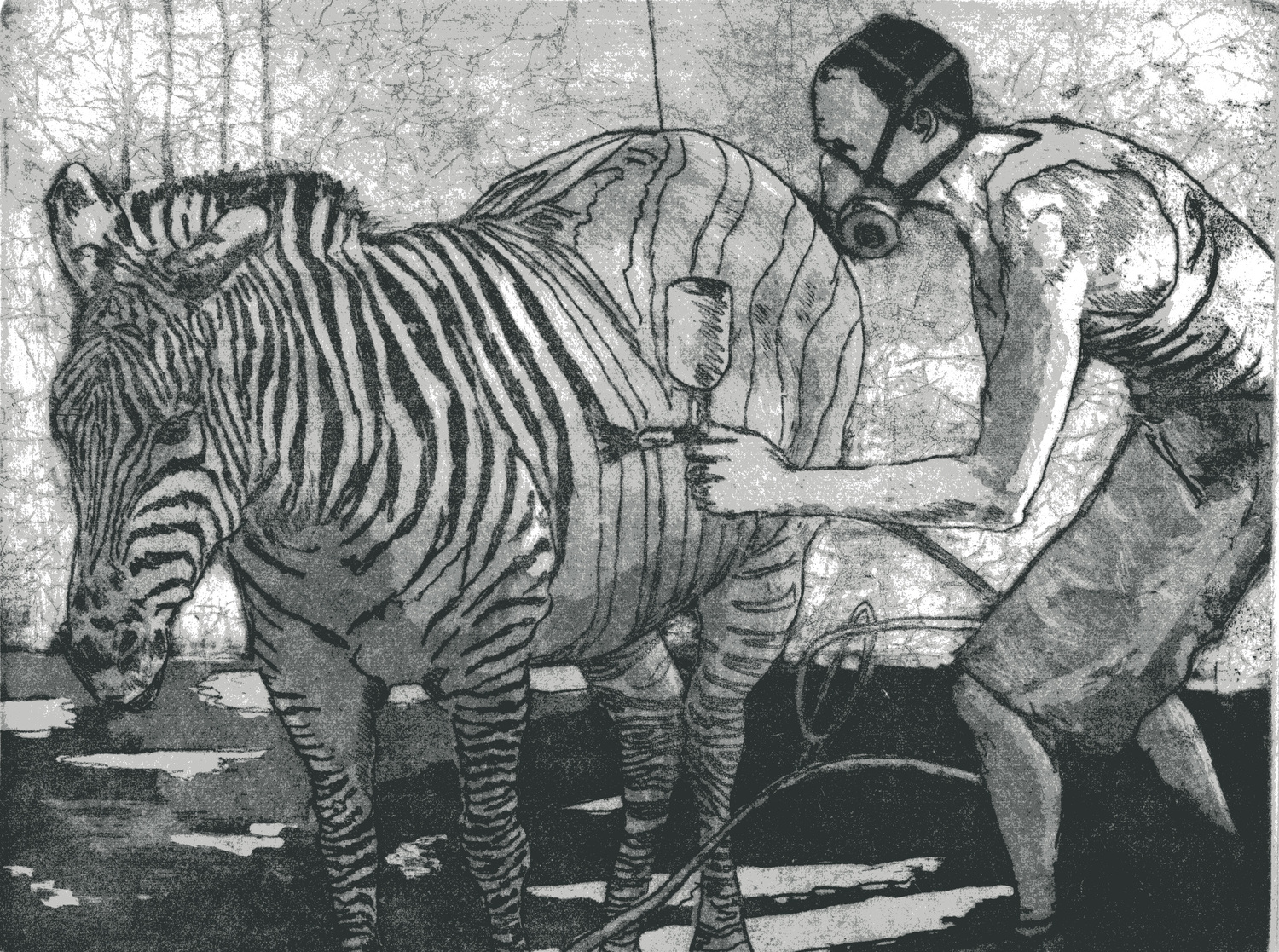

“Custom Striping” by David Williams captures nicely the “cleverly-painted mule” species of examples that arise in epistemology:

http://www.under-pressureart.com/davids-misc/copy-of-custom-striping

“No Object Implies the Existence of Any Other”, Ian Burn (1967)

Photo taken in the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2013.

I took this to be a statement of Hume’s idea that there is no necessary connection between distinct existences. When I showed it to Mark Colyvan, he immediately said “That’s false! The number 2 implies the existence of the number 3.”

The photo itself contains a philosophical puzzle. The museum’s photography policy was that you could take photographs of the art for non-commercial use, with the exception of aboriginal art. The object on the opposite wall, reflected in the mirror, is a piece of aboriginal art. So did I break the rule?

James Joyce, “Tułacze” (Exiles) poster: http://artnectar.com/2010/07/36-illustrated-polish-theater-posters/polish-poster-8/

And Polish poster art in general.

Robert Rauschenberg’s “This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so” is my pick.

This piece more questions art and specific art forms than showing a philosophical issue. Unless you have a definition as something grounded in philosophy, which it is actually. I see the point now.

Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party, at the Brooklyn Museum, Hypatia’s place setting.

http://www.ipernity.com/doc/laurieannie/24352451

As a philosopher of art, just wanted to share that I love this thread <3

Artwork by Phillip Norris (Untitled):

“Be a philosopher; but, amidst all your philosophy, be still a [human being].” – Hume

I have a couple of my own artworks which express philosophical ideas; hopefully that’s allowed!

The first is an oil painting inspired entirely by the Pattern Theoretics invented by Dynamical Chaos Theorist and AGI researcher, Ben Goertzel.

The second is a metaphorical allusion to Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya or, The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom, the famous Mahayana sutra expressing the philosophical notion of sunyata – the idea that all phenomena are empty of inherent existence. The images are readily available on my short blog.

“House I” by Roy Lichtenstein evokes Fake Barn Country, for sure, but also more general questions about trusting one’s senses and the nature of perception.

via Gfycat

There’s Klimt’s “Philosophy”

Philippe Chuard brought this conversation to my attention, knowing that I might have something to say about The Museum of Philosophical Artworks.

I don’t believe such a thought experiment would be complete without Andy Warhol’s “Brillo Boxes” (1964). (https://www.nortonsimon.org/art/detail/P.1969.144.001-100)

Who can forget the effect of these works on Arthur Danto? Why, he spent a good portion of his intellectual career explaining how Warhol’s work at Stable Gallery was an epiphany for him, raising the issue of indiscernibles? “…[T]he Warhol show raised a question which was intoxicating and immediately philosophical, namely why were [Warhol’s] boxes works of art while the almost indistinguishable utilitarian cartons were merely containers for soap pads?” (Danto, “Art, Philosophy, and the Philosophy of Art”, 1983). But what if we invert the challenge and ask artists what philosophy has meant to them?

Conceptual artists such as the Art & Language group (of which I was a part), Joseph Kosuth (already selected), and Adrian Piper (an artist with a PhD in philosophy, supervised by W. Quine; keynote speaker at the British Society of Aesthetics annual convention, 2013; and subject of the most extensive retrospective held for a living artist at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3924) have all been interested in the analytical philosophy of language, the pragmatics of natural language, aspects of Wittgenstein’s philosophy, and the work of Pierce.

We can also cite Hans Haacke’s interest in systems theory and the political philosophy of Jürgen Habermas, or John Latham and Barbara Stevini’s interest in the work of physicist/philosopher David Böhm. Let’s not forget Thomas Hirschhorn, who has produced three “monuments” to philosophers — Gramsci, Bataille, and Deleuze — and writes that artists should love philosophers (see: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/07/29/house-philosopher).

There are many more philosophers of art, etc., who have been enthralled with particular works of art, like Heidegger reflecting on Van Gogh’s “Shoes” (don’t forget Meyer Schapiro’s response!), or Theirry DeDuve’s interest in the Kant-Duchamp axis (the “Readymade”, ca. 1913, is paradigmatic for the later institutional theory of art). But why should art only be examined in terms of the assumptions of philosophers?

The question of art and philosophy, from the artist’s point of view suggests that there may be more modes of engagement between art and philosophy than the “service” mode or the illustration of philosophical issues by visual means. The question that interests me at the moment is whether or not the engagement of art & philosophy might constitute an interdisciplinary field (https://invisible-college-conversations.com/2019/01/01/rethinking-art-and-philosophy-as-an-interdisciplinary-field-2019/). So, we wouldn’t necessarily end up with a Museum of Philosophical Art; rather, a colloquium of artists and philosophers.

I will add another of my suggestions to this post: An Oak Tree by Michael Craig-Martin

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/An_Oak_Tree

https://www.google.com/search?q=this+is+a+copy+schrenk&tbm=isch&source=univ&client=firefox-b-e&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj9-dvBn77hAhUSneAKHa-hC5IQsAR6BAgEEAE&biw=1368&bih=798#imgrc=C9f7CsO04wvRYM:

A Review by Sonja Frenzel

At a time when copyright issues are debated ever more heatedly, an artwork titled True Copy may appear as more than a slight provocation. Above all, its aesthetic play on the legal, ethical, as well as ontological and epistemological dimensions of copying challenges us into re-considering some of the most pivotal questions surrounding truth and originality: What is a copy? When is this copy a true copy? How do (true) copies relate to their original/s?

10,000 postcards proclaiming “this is a copy of the original” cannot be lying. Paradoxically though, they reproduce an original which, for its own part, must be lying. It is this original that affirms, in the first place: “this is a copy of the original”. A similar predicament is well-known in philosophical logics: The Liar is a sentence stating about itself that it is false. It revolves crucially around the unresolvable paradox of speaking the truth if it is lying, and vice versa.

Escher’s “Three Worlds”: Three disjoint models of causality / identity / being. 1. A “Platonic” picture of participation and exemplarism, mirrored by the inverted images of the trees on the lake; in particular, by the inverted branching structure of the trees. The base of the tree represents the exemplar, and the branches, the manifestations. That the exemplars are not concrete things in the world is mirrored by the trees visible (in the picture) only as reflected images. The anthropologist Levy-Bruhl has shown how this picture might work outside of philosophy, in culture. 2. The leaves on the surface of the lake picture the world of one-to-one causality, where any concrete thing might cause any other (for example, Hume), and all causal accounts are individual to individual. Finally, 3. The fish immersed in the depths of the lake pictures a world of individuals immersed in an environment, the entirety of which has to be taken into account before any complete causal account can be given.

https://www.christies.com/lotfinder/Lot/maurits-cornelis-escher-1898-1972-three-worlds-5677590-details.aspx

.jpg)

Mark Tansey:

The Innocent Eye Test, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/484972

>In this wry painting, a cow stands in front of Paulus Potter’s The Young Bull, 1647, now at the Mauritshuis, The Hague, while the human experts wonder if the cow can distinguish artifice from reality. Will she bellow a greeting, or admire Monet’s Grainstack (Snow Effect), 1891, on the wall to the right? Tansey offers this critique of the role of representation in modern art as a method of revitalizing the tradition of painting. His use of grisaille, or grey monochrome, relates to the tradition of academic painting but also to his job as an illustrator for The New York Times. Such strategies of appropriation define much of the art of the 1980s in New York, where Tansey still works.

Achilles and the Tortoise, https://biblioklept.org/2019/01/22/achilles-and-the-tortoise-mark-tansey/

>We shoot a rocket, plant a tree, and celebrate ourselves, and yet the tree in the background has long been there before us.

Couple of classics:

#/media/File:Hans_Holbein_the_Younger_-_The_Ambassadors_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein contains a striking skull memento mori that is meant to remind the viewer that death is inevitable for all.

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by the studio Breughel: “…a transcription of the strange sensation of “already having been” which is brilliantly evoked by Breughel in the view of a world serenely pursuing its own concerns, completely oblivious to the almost invisible tiny pair of legs waving pathetically out of the water, the only record of the apocalyptic event being a pair of feathers floating disconsolately down in the wake of their erstwhile owner.”

I like Genis Carreras series of prints capturing philosophical ideas: https://studiocarreras.com/philographics

Nice examples – I especially like Mark Tansey’s Cow, which I was just reading about in a 1998 J. of Consciousness Studies article on brain mechanisms of perception.

Surprised no-one has posted this yet (so far as I can see):

Goya – The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (self-explanatory?)

https://www.julieelizabethkirsch.com/brainsmindsselves

I can’t link to just one – many more coming soon on brains, minds, and selves!

First one that comes to mind, don’t know why, is Bosch – and Kandinsky.

I also did a search for Michael Jackson’s Dangerous album, which reminds me to Bosch’s paintings… and found it is Mark Ryden who made the album artwork. After looking at some of his works, i am not sure how Philosophical they are, yet this one may be interesting for discussion, 58 the Apology.

https://www.markryden.com/paintings/treeshow/index.html

Kandinsky’s work is without doubt, an interesting approach to music and philosophy through painting, at least to me, it includes Euclid’s geometry Elements, from where you can arrange different ways of structuring logic, and language. Nevertheless, it is not great to define art… i prefer to experiencing it.

I like this image as a representation of anarchism: http://www.funnysigns.net/files/no-birds.jpg

As relevant today as in 1896, Jean-Léon Gérôme’s “Truth coming from the well armed with her whip to chastise mankind” (“La Vérité sortant du puits armée de son martinet pour châtier l’humanité”).

Title inspired by Democritus, “Of truth we know nothing, for truth is in an abyss”

Life before Twitter.

My visual work is based on an understanding of oneness of all of life and I tend to write poetry to it.

This painting in particular, emphasise light and illumination, in relation to Japanese philosophical interpretation of the physical and metaphysical senes. I am also interested in orders and cyclical natures.

whats the artist and title of this piece?

I’m not great at cutting and pasting from the web, but Jasper Johns was supposed to have been heavily influenced by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Evidence for this can be found in a painting by Johns in which no two blocks of color share the Same color, a canvas Johns himself said he meant to represent a concept he had read in Wittgenstein about the way in which concepts or ideas do or do not “share borders” with other concepts or ideas.

(This example is taken from Fred Orton’s largely academic treatment of Johns’ work ‘Figuring Jasper Johns’, which, while “academic” is a useful treatment of a wonderfully fascinating artist.)

The famous statue of Plato was an inspiration in this painting of mine. The awe I have whenever I see images of him in indescribable.