Visualizing the Structure of Philosophy from the 1950s to Today

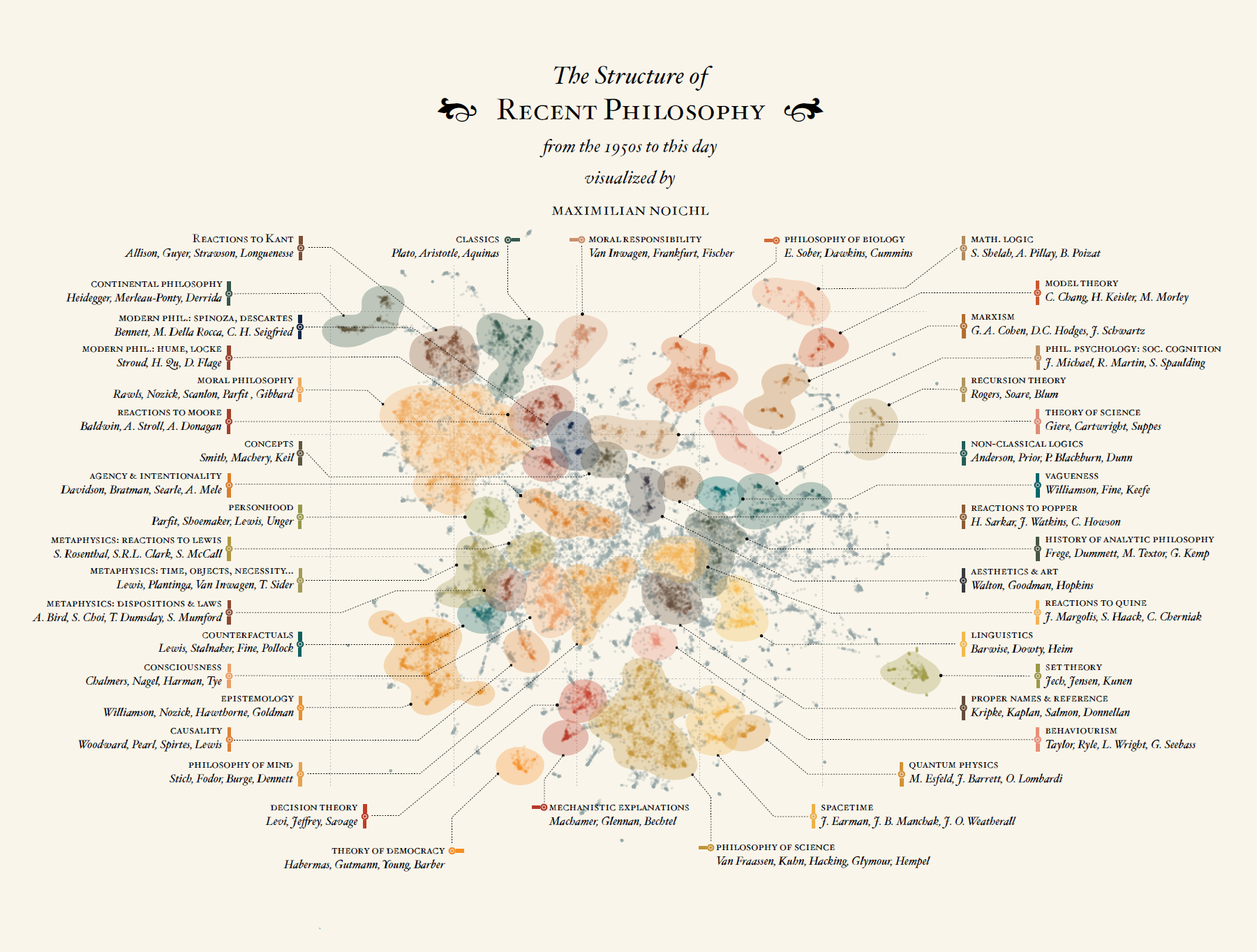

Maximilian Noichl has designed a beautiful visualization of philosophy from the 1950s to today.

Looking somewhat like a map, the visualization is based on 55,327 papers in philosophy from the Web Of Science collection. Noichl says: “the papers were determined by snowball-sampling: I started with a small sample (a few thousand papers), and extended from there by repeatedly looking at the most cited publications.”

This is how the image was put together:

Articles from various philosophy journals were spatially distributed according to their citation-patterns. Every point represents one of these papers. The papers were then grouped by a clustering-algorithm into 42 clusters which are represented by the colored shapes, and which are labeled around the graphic.

Here’s the result:

The original version of “The Structure of Recent Philosophy from the 1950s to this day” is on his site and is accompanied by some explanatory text. Here’s an excerpt in which Noichl discusses what he thinks can be seen in the visualization:

The clusters are a bit heterogenic in their nature: while some are thematic, others are determined strongly by specific persons or eras, which seems in itself to be an interesting observation about the structure of the literature. But we can discover more: there is, for example, a remarkable cleft between theory of science and epistemology. And the way various historical clusters group themselves around moral philosophy suggests an internal relation. We can also observe that continental philosophy is a distinct cluster that seems to split into two halves, but is well-formed and not that far away from the rest of philosophy.

You can see other visualization Noichl has created at his website, including a delightful depiction of the interrelation of the ideas of ancient philosophers over time, a graph charting recent trends in philosophy, and an alternate version of the one featured in this post

(via Daniel Brunson)

I think that this needs to be taken with an extremely large grain of salt. The data source, Web of Science, has, as far as I can tell, very spotty coverage.

Out of curiousity, I did a bit of searching on Web of Science in the literature I’m familiar with. In the philosophy of QM, two influential and highly cited works are Tim Maudlin’s Quantum Non-locality and Relativity and David Albert’s Quantum Mechanics and Experience. Google scholar lists 783 and 1,017 citations of these books, respectively.

Neither book exists, according to Web of Science. David Z. Albert, says Web of Science, has a career total of 4 publications, and has been cited 18 times. Tim Maudlin, according to Web of Science, has a total of 20 publications, and has been cited 83 times.

If the coverage in other areas of philosophy is comparable, it is hard to imagine that the end result is of much use.

The coverage of the WOS is not spotty (though by no means exhaustive). But you were looking for books in what is (mainly) a database of articles.

Points represent articles, but are arranged using also the data of books they cite (which is indexed by WOS). The whole project, including the sampling strategy, is documented here:

https://homepage.univie.ac.at/noichlm94/posts/structure-of-recent-philosophy-ii/

My query for Prof. Albert (“AUTHOR: (Albert DZ)”) yields 46 publications, the most cited one has gathered 1005 citations in the core collection.

But putting that aside, I totally agree that WOSs method of counting citations is pretty unreliable. It does, on the other hand not really matter for the project.

Thanks for this, Maximilian. I was querying author “Albert, David Z.”, rather than “Albert, DZ”. As you note, the latter query picks up more entries. But it still misses the books.

As you say, in the examples I chose, I was looking for books in what is mainly a database of articles. That raises two questions: (1) How comprehensive is WoS’ database of articles, when it comes to philosophy? and (2) Can one limn the structure of recent philosophy without the books?

With respect to the former question, I did some unsystematic spot-checking, comparing Google Scholar citations with WoS citations. In most cases WoS missed most of the citations that Google Scholar found. As for the latter, I suspect that it varies between subfields of philosophy. I suspect there are subfields of philosophy in which most of the action occurs in the journals, others that are more book-oriented.

WOS is quite picky about names, as author disambiguation is a big problem. Google scholar has been criticized for inflating citation counts, although, honestly I don’t really know what to make of that.

But I think that I see your point now. Some people I talked to were concerned that the missing books might be the reason that continental philosophy is so small.

I would certainly be cautious in (over-)interpreting the size of the clusters. Some are very dense — lots of papers close to each other — and therefore look smaller than they actually are, compared to others. This kind of visualization just doesn’t lend itself very well for group comparisions of size, it has other merits.

I’m not sure that the visualization would change drastically if one were to add books: As every book that that is cited by an article has an effect on the position of the point in the graphic, they have done most of their work already and would probably only inflate and deflate some clusters a bit. But one would invite a whole lot of new problems of demarcation: I can be quite comfortable in saying that an article published in a peer reviewed journal can be counted as academic philosophy. But I’m under the impression that if one were to throw in books, it would be quite hard to find a principled approach of inclusion (maybe reviews)?

But it’s a legitimate critique.

I believe that WoS also does not reveal chapters in edited volumes — though this may have changed over the years [though if books are not counted, I suspect chapters in books are also not counted]. This has a significant distorting effect in some sub-disciplines, as sometimes some of the more interesting work — that of exploring non-dominant questions, and so trying to jumpstart new lines of inquiry — appears in edited volumes.

I would also draw your attention to a very good white paper out of the University of Waterloo on bibliometrics. I realize that your focus is not bibliometrics, but the paper does an excellent job reviewing the strengths and weakness of existing bibliometric databases and tools. https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/handle/10012/10323/Bibliometrics%20White%20Paper%202016%20Final_March2016.pdf

Thank you for the white-paper: I was not aware of it, and it seems pretty useful.

The WOS has only a few thousand book-chapters in philosophy, which are not included in the data I treated. I have no estimation of the total output in this form, but I suspect it is far higher. And WOS standards of inclusion are quite opaque to me.

Generally speaking, it seems to me that a method that looks at citations (even though it makes in my case no business of explicitely counting them) will be bad at representing non-dominant or even marginalized scholarship. I have not really found an elegant solution to this problem and I’m thankful for suggestions.

I see reactions to Quine, but where’s Quine?!?

Every one of the ~50.000 tiny points in the graphic represents an article. Some are probably by Quine, but there is no telling (at least in the graphic) where they were positioned by the algorithm. But there are a lot of papers that are brought together basically because they cite Quine. They form a more (or, in this case more or less) coherent cluster, which is large enough to be picked up by the clustering algorithm.

I hope this is helpful. 🙂

You might be also interested in this (an analysis of a single philosophical journal’s citations): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23801883.2018.1478233

Thank you, that’s really neat!

Sartre? Wittgenstein? I love these things, but there are huge gaps.

Oh, they are in there. The names are not meant to be exhaustive, they just give clues on how to interpret the clusters. So if you are missing someone important, you should usually just imagine that his name has been gobbled up by the margins of the chart. I think I have been quite principled in my approach to choose names as markers, and I give more details on this on my website. To quote from there:

“I then labeled the clusters by hand, identifying them by looking at the most frequent words and bigrams in the abstracts, the authors of the most cited works, and the most prolific authors in the field. To give an idea of the contents of each cluster, I added names of the most cited and most prolific authors, identifying the latter by mentioning them with their initials. While the most prolific authors can not always be understood to have shaped the field in a deep fashion, they anchor the clusters in more recent debates, and give me an opportunity to mention more women in the graphic. “

Peter Singer? One of tbe greatest of contemporary philosophy

Please look at my comment above: People that are not present in the labeling are not missing in the data.

Oooh! I want to get in on this!

Why didn’t you include my favorite philosopher? She’s a really big deal and I don’t see her name on your graphic so it’s obvious you’re a hack.

/s

I actually think this is pretty cool. Students often ask me how this or that field of philosophy fits in with the rest. This gives an easy way to explain why these questions, even though they’re good questions, are hard to answer.

One actual criticism: nearly all the names you use to identify areas are names of men. Since women have been *very* influential in the period you’re looking at, this suggests some flaw in your method of choosing these names. I am not, however, competent to say what the flaw might be.

I actually mention this problem in the text that explains the graphic (It has been cut off on daily nous, I suspect for aesthetic reasons. You can see the full version here: https://homepage.univie.ac.at/noichlm94/posts/structure-of-recent-philosophy-iii/).

The basic answer is: Never underestimate the unwillingness of philosophers to cite women in their research. I did actually some of-the-cuff calculations during this project, and my result were very similar to those of Kieran Healy, who finds that:

“Nineteen items in the data [500 most cited in four major philosophy journals between 1993 and 2013] are written by women, or 3.6 percent of the total. By comparison, 6.3 percent of the items in data are written by David Lewis.” (https://kieranhealy.org/blog/archives/2013/06/19/lewis-and-the-women/)

(read that sentence again…)

I choose the names based on two factors, actual citation scores (those are the names without initials) and most papers in the field (names with initials), a method that I initially chose as I hoped I would be able to mention more women.

That’s… really disappointing. Thanks for the info, though, and for sharing this.

Two older papers: Cullars (1998) who found 70% of citations in monographs from the 1994 Philosopher’s Index were to monographs (14% to collections, 10% to articles); 11% of citations were negative/unfavourable 😉 And Kreuzman (2000) on epistemology v. PoS : “A great deal of caution is needed here when we use the terms `intellectual closeness’ and `intellectual distance’. Closeness and distance do not refer to the similarities and dissimilarities of their views. For example, Kuhn and Popper have a high correlation coefficient (i.e., 0.98). Their views clearly are not the

same, but they are `intellectually close’ in the sense that their views are competitors and they are often linked in articles. On the other hand, Lehrer’s and Toulmin’s correlation coefficient is -0.70. Their views are intellectually distant; their views are rarely linked.”

Thank you for your remarks. 🙂 Kreuzman does a very similar thing to what I am doing (mapping, then clustering). As there has been some progress in the machine learning-department, it would be very interesting revisit his paper in detail. I have done actually a comparison to his (2001) Scientometrics paper in a talk I gave on this subject:

https://homepage.univie.ac.at/noichlm94/full/CMP2018/presentation/index.html

You will have to click yourself through, and then down. (Slide: “A LITTLE REALITY CHECK…”)

You are completely right though, this method does not identify positions. It identifies what positions are on, so to speak. It is obvious why Popper and Kuhn are cited together, its because they have a common subject to disagree about. I am thinking on ways to model actual positions in literature databases, but nothing of substance has come out of it until now.

And I would agree with Kreuzman that the interpretation of the distance metric (in my case cosine-similarity) is not trivial. I think the results suggest, that there are actually various modes in which literature-clusters form: There are clusters defined by commmon subjects, there are clusters that are strongly defined by persons, and there are clusters that are defined by historical periods (I suspect that there are also clusters defined by language of the literature, e.g. ancient greek or latin). And within these clusters the distance metric means different things, which I think is pretty interesting.

I am not sure, was your focus in citing Cullar on the negative citations? (It is a delicious oddity of philosophical literature that there are negative self-citations.) Or more on the citation of monographies? Because as I do not work with network data, citations of monographs do have an (probably overwhelming) influence on the position of the points, although monographs are no datapoints themselves.

This is a really neat project! There are obviously some limitations with representing this in a two-dimensional projection. The one that jumped out at me is that Marxism appears to fall in the gap between Philosophy of Biology/Theory of Science/Non-Classical Logic/Vagueness and Mathematical Logic/Model Theory/Recursion Theory! It’s also interesting that Set Theory and Linguistics are somewhat far from these clusters, though the bridge is History of Analytic Philosophy and Reactions to Popper and Reactions to Quine.

Exactly. The two dimensions are certainly too few to do the data justice. If we had an actual classification-task at hand, I would reduce to maybe fifty, and cluster on that. I’ve run some tests with that, and the results get better. The trouble with two dimensions is that small and tight clusters, like Marxism or Habermaßian thought can end up pretty much everywere, because the algorithm has not enough data to relate them meaningfully to their surroundings.

Van Inwagen, Fischer and Frankfurt, but no Russell, Moore and Wittgenstein? No Wittgenstein in philosophy from the 1950’s to the present?

Moore actually has his own cluster, look in the upper left corner. But your question points to a common misunderstanding, as DailyNous has unfortunately cut off the explanatory text from the picture. The names are not meant to give a ranking of most important philosophers. I am not interested in that. They are meant to help identify the clusters. And the clusters are regions of particular density in the graph, which means high homogenity

in the data.

If an important philosopher does not appear to have his own cluster, or doesn’t appear in a label, this only means that there is no region in the graph that is particularly defined only or, or at least mostly, by him. I would interpret this result more in the direction that there are, even though the term exists, no “Wittgensteinians” as a distinguishable group, while “Popperians” actually form a group of some density, as do “Marxists”. This is no votum on the overall size of the influence of Popper or Wittgenstein, but might tell us something about its kind.

And not all of the names are actually meant to be read as influential. Some, which are mentioned with their initials, H. Sarkar, are philosophers that are highly productive recently in the cluster. They have, so to speak, authored most of the datapoints.

I hope this helps lessen your disappointment.

MN

Not even “Reactions to Wittgenstein”, say?

Under reactions to Popper there is “Sarkar”.