Who Are Philosophers Less Willing To Hire?

George Yancey, a professor of sociology at the University of North Texas who works on anti-Christian attitudes in the United States, has researched bias in academia, and recently shared some information he had collected regarding philosophers’ hiring preferences.

He writes:

I did this quick breakdown of some of the different groups and the willingness of academic philosophers to hire them. Note that their unwillingness to hire them may be slight or may be strong. This is only the percentage that have an unwillingness to hire someone because they are a member of this group. I do not have the time right now to do a breakdown by being slightly, moderately or strongly more unwilling to hire from that group but do not want to overestimate the degree of rejection either.

The data was collected as research for his 2011 book, Compromising Scholarship: Religious and Political Bias in American Higher Education.

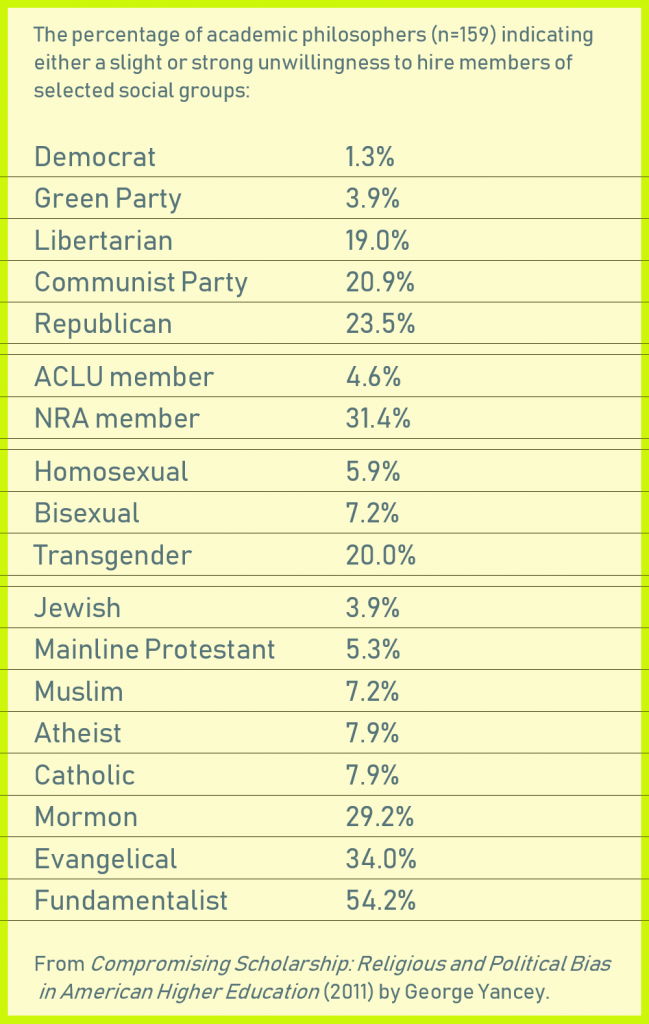

What follows are the names of the groups Yancey asked about followed by the percentage of the 159 philosophers he surveyed indicating either a slight or strong unwillingness to hire members of that group:

Yancy adds:

I think philosophy does better than most humanities and social sciences but not as well as the natural sciences with it comes to accepting deviate social groups. As a sociologist I have no dog in that fight and am just telling it like I see it.

Discussion welcome. Please be respectful of each other and mindful of stereotypes.

“I think philosophy does better than most humanities and social sciences but not as well as the natural sciences with [when] it comes to accepting deviate social groups.”

What’s the evidence for this? (I’m not necessarily doubting either claim, I’m just wondering what the evidence looks like for these two claims – presumably in his book?).

Also, I found it interesting that there is one category for “Muslim” but for Christianity there is Catholic, Protestant, Evangelical, etc.” I guess that is because of the demographics he’s interested in?

Table 5.1 (p. 209) of Yancey’s book compares some of these numbers across ten different disciplines. Here are the numbers for unwillingness to hire Republicans (rearranged in order from most to least):

Anthropology 32.3%

Sociology 28.7%

Language – English 26.9%

Philosophy 23.5%

History 22.5%

Chemistry 16.4%

Language – Non-English 16.1%

Political Science 15.4%

Experimental Biology 10.9%

Physics 10.0%

That doesn’t support the quote Chris questioned. That shows that phil is in the center of that sample (three humanities/social sciences above and three below).

The orders are slightly different for different groups, e.g., for NRA members philosophy is the 5th (out of 10) most tolerant overall and the 3rd (out of 7) most tolerant out of the humanities/social sciences. It’s hard for me to say whether on the whole they support the claim that philosophy does better than most humanities/social sciences (especially because it’s hard to extrapolate just from these 7), but it does seem that we can at least say that philosophy does worse than the hard sciences, and that it’s neither the best nor the worst in the humanities/social sciences.

Hey Chris. Good question. But most academics in the United States would not be able to distinguish between Shi-ite and Sunni Muslims or know what Wahhabi Islam is. But they do understand different Christian groups. Thus I got more info by looking at different Christian groups but would not have gotten that info from breaking down the Muslim groups. Hope that answer your question. Have a good day.

Any data on who these philosophers are? Full time faculty? At what kind of university (R1, R2, small state university, SLAC, community college, etc.)? Working where (east/west coast, the south, Midwest, etc.)? Gender breakdown? Anything more than “159 philosophers”?

I have the data for those breakdowns except for maybe full time faculty. I think almost all of them were but I did not ask specifically. Was there a particular demographic aspect you are interested in. I can look that up fairly quick. It would take me longer to do a full demographic analysis of the philosophers.

Thanks, George!

Obviously don’t feel like you have to answer these, but off the top of my head, I’m interested in:

1- The relationship between geographical data (e.g., faculty in the south vs. west coast) and the attitude towards Republicans or Communists.

2- The relationship between prestige/class (faculty at R1 and SLAC vs. faculty at poorer places) and those attitudes.

3- The relationship between gender breakdown and the attitudes towards transgender individuals.

Also, I don’t have access to the book. I imagine you have already analyzed some of these data for outside philosophy..

1.I thought I had geographic data but I don’t. Sorry about that. \

2. The prestige of the faculty as measured by the level of degree offered by the program has no effect on these attitudes.

3. Men are more likely to reject transgender individuals than women.

Remember that the last two results only apply to academic philosophers and I do not know if they would hold up with the entire sample.

How was the sample selected? What was the response rate? Could there be self-selection bias?

I used directories and obtain a random sample of respondents. I do not see how there could be self-selection bias but there could be non-response bias. In the appendix of the book I discussed what I did to see if that type of bias may have shaped the results. I do not think that it did.

You indicate in your book that respondents sometimes replied to your email address declining to fill out the survey. Does this mean that the survey was sent by you personally? If so, it seems clear to me at least that there was quite likely a self-selection bias; people willing to respond to a survey written by George Yancey.

There’s also an indication in your book that not all who received these surveys for philosophers were in fact employed philosophers. Hence not on hiring committees. Is that right?

Yes as not all of the philosophers in the directly work on a university campus. However for this particular chart I only included those that stated that they worked in an academic setting.

Sorry that should be directory and not directly. Was typing too late last night.

The figure concerning fundamentalists doesn’t surprise. Philosophy ought to be about following the reasons, evidence, and argument. Fundamentalists are, it seems clear, quite often opposed to doing that (even if they hide their inclinations under a fig leaf by invoking Plantinga’s views regarding “properly basic” beliefs).

This is the kind of attitude we fundamentalists have to deal with in academia. Nobody seems to like us very much!

I wonder if you’ll share the “reasons, evidence, and argument” you have for the claim that fundamentalists are using Plantinga’s work disengenuously.

Carnap’s comment is silly, to say the least. But it does give me a great excuse to bust out Plantinga’s views on the term “fundamentalism”!

“I fully realize that the dreaded f-word will be trotted out to stigmatize any [epistemological] model of this kind. Before responding, however, we must first look into the use of this term ‘fundamentalist’. On the most common contemporary academic use of the term, it is a term of abuse or disapprobation, rather like ‘son of a bitch’, more exactly ‘sonovabitch’, or perhaps still more exactly (at least according to those authorities who look to the Old West as normative on matters of pronunciation) ‘sumbitch’. When the term is used in this way, no definition of it is ordinarily given. (If you called someone a sumbitch, would you feel obliged first to define the term?) Still, there is a bit more to the meaning of ‘fundamentalist’ (in this widely current use): it isn’t simply a term of abuse. In addition to its emotive force, it does have some cognitive content, and ordinarily denotes relatively conservative theological views. That makes it more like ‘stupid sumbitch’ (or maybe ‘fascist sumbitch’?) than ‘sumbitch’ simpliciter. It isn’t exactly like that term either, however, because its cognitive content can expand and contract on demand; its content seems to depend on who is using it. In the mouths of certain liberal theologians, for example, it tends to denote any who accept traditional Christianity, including Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, and Barth; in the mouths of devout secularists like Richard Dawkins or Daniel Dennett, it tends to denote anyone who believes there is such a person as God. The explanation is that the term has a certain indexical element: its cognitive content is given by the phrase ‘considerably to the right, theologically speaking, of me and my enlightened friends.’ The full meaning of the term, therefore (in this use), can be given by something like ‘stupid sumbitch whose theological opinions are considerably to the right of mine’.’

Over the past few years I’ve commented several times on this site under the pseudonym “Gray.” In case anyone’s confused, I’d just like to point out that I’m non-identical with the “Gray” above.

Presumably, if someone isn’t good at following the reasons, evidence and argument, you will be able to infer that from their writing sample, references and publication record. Inferring it on the grounds of a group generalization from their religious leanings is more or less the definition of group-based discrimination, which in other contexts is – rightly – thought of as unacceptable.

It’s not that simple when we’re talking about groups whose membership is determined (at least in part) by belief. We’re each accountable for our beliefs. Say you’re on a search committee and an applicant has the view that (L & ~L) is a theorem of classical first-order logic. (To be a little redundant, I’m not talking about a dialetheist who holds that L&~L is a theorem, where ‘L’ is short for the Liar sentence, in some dialetheist system that’s sufficiently rich language for diagonalization. I mean someone who thinks classical logic lets us derive L&~L.) Even if he never makes use of that belief in the rest of his application package, his having that belief is still evidence that he’s not a good candidate for the job, because it’s a really bad belief. That poor judgment might exhibit itself in other ways once he’s on the job.

Presumably the same sort of consideration counts against hiring those with beliefs not quite as easily falsified, but which still show evidence of poor judgment. E.g. flat earthers. I presume the 54% in this survey think Christian fundamentalists, by holding the beliefs they do, demonstrate poor epistemic judgment. (I am a Christian fundamentalist of sorts, so naturally I don’t agree with this conclusion.) You’re always going to have tons of applicants without this epistemic red flag, especially in this market. Why not hire one of them instead?

This is a fair point, which I’d considered when I commented but probably should have engaged with more fully. (And kudos to you for bringing it up, against interests.)

The reasons I think discrimination on religious/political grounds is *mostly* analogous to discrimination on sexual/racial grounds are (in no particular order):

1) While religion (or lack of religion) is partially a matter of rational assessment of the evidence, it’s implausible to think that’s the sole or even the main driver. The correlation between your own religion, and the religions of your family or community, are really good. So while religion isn’t quite as immutable as, say, race, it’s also not well analyzed by considering it as a rational choice made by adult philosophers. At least to a substantial degree, it’s something you’re born into.

2) The correlation between rationality and expertise in one area, and that in another, is in my anecdotal experience pretty noisy:

– physicists and philosophers just think differently; a really good philosopher can be a terrible theoretical physicist

– really smart academics often have really silly, uninformed politics, and repeat party-line arguments with no real appreciation of the counter-case

– some absolutely brilliant scientists have had completely mad views on other topics, political or otherwise

– in my experience of academic admin, really intellectually impressive people are embarrassingly naïve at understanding the issues.

I’m not sure why this is true (I’d guess 25% non-transferrable skills, 75% intellect isn’t useful unless you take seriously the task of getting on top of the factual issues) but as long as it is true, assessment of academic aptitude in one area is an unreliable guide in other areas.

3) I think there is a general moral/prudential principle that inferences of the form “A correlates with not-B, we value B, therefore disregard applicants with A” are inadmissible when the correlation is not too tight and A is something that is not freely chosen. (Hence, the question of whether women, on average, are better at geometric reasoning is properly set aside when assessing individual applicants for a math position.)

4) While obviously I think that your agreeing with me on substantive position X is good evidence that you are an intelligent, clear thinker, it is in the collective interest of academia to be very cautious applying that reasoning process, given the evidence that people and groups are often wrong. It’s really not okay for me to preferentially hire advocates of the Everett interpretation of quantum mechanics, even though – since I think the interpretation is right! – I regard accepting the interpretation as ceteribus paribus evidence of good sense. And it’s not okay because the collective practice of hiring on that basis is not conducive to dissent and to the free exchange of ideas.

@David Jones Wallace, your last point – 4) – puts me in mind of David Lewis’ paper on academic appointments, here: http://www.andrewmbailey.com/dkl/Academic_Appointments.pdf. Probably you’ve read it! But if not – or for those who haven’t – he discusses reasons why one might not use taking an applicant to be right as a criterion in hiring that applicant.

do we have a list of true doctrines in philosophy? if so, what are they? I don’t me “believed true” or “widely accepted today” or anything like that. I mean “is true.” I’d like to see the canonical list of philosophical turths.

If a job candidate had a decent writing sample and publication record in their area of specialization but, outside of their academic work, was an advocate for say crackpot conspiracy theories, or young earth creationism then I would have serious doubts about whether they would be worth hiring despite their good track record in their area of specialization.

Yes, exactly, and also those who believe in panpsychism, Meinongianism, the conjunction of materialism and moral realism, etc.

Young-earth creationism is exactly the right example to put pressure on my view. I *really strongly* feel that being a young-earth creationist is evidence of intellectual weakness.

… I think, notwithstanding (and not without discomfort) that I want to commit to the view that being a young-earth creationist is not in itself relevant to a hiring decision. If somehow you’ve managed to be a clear sensible thinker about X despite your creationism, fine. If you haven’t, that can be picked up in other ways. (This is in fields other than biology.)

Why think this? Various reasons, but mostly that otherwise there’s a slippery-slope argument, as Joshua Reagan’s comment suggests. Once we start deeming views so stupid that we can reject their adherents without first-order consideration of their scholarship, where do we stop? A prominent philosopher (Galen Strawson) referred to the view I hold on philosophy of mind as “the silliest claim ever made”. I think his view on consciousness is comparably ridiculous. Do we really want an academy where I reject applicants for a philosophy of science job because they agree with Strawson on philosophy of mind, and he rejects applicants for a metaphysics job because they agree with me?

Allow me to try and put some more pressure on your view. Someone’s being a young-earth creationist shows at least an unreasonable reluctance to take some widely accepted scientific theories seriously. And that is a major flaw for a philosopher. This, I think, doesn’t apply in the case of “silly” philosophical views mentioned above.

According to widely accepted scientific theories, objects exist. Yet object nihilism is a “silly” philosophical view that is defended by scholars. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/object/#ExisNihi

The boundary between science and metaphysics doesn’t seem particularly sharp to me. If we allow scholars with strange metaphysical views, it seems that this might sometimes have strange scientific consequences.

I intended to write “…it seems that *these* might sometimes have strange scientific consequences.”

Joshua, which scientific theories do you think entail the existence of composite objects of the sort denied by nihilists?

Palaeontology? “Sauropods are herbivores” entails “some things are herbivores”.

Presumably the compositional nihilist has an error-theory reconstruction of palaeontology in mind, but the literally-interpreted theory looks incompatible with it.

That doesn’t seem so much like a scientific theory entailing that there are composite objects as a scientific theory inheriting a way of talking from ordinary language or common sense. Maybe I’m misunderstanding, but I thought Joshua’s point was that science gives us some extra special reason to think that nihilism is false. But the sauropods example doesn’t look like it gives us any more or less reason than we already have from everyday life.

I agree that some reconstruction is required, but I’m not so sure that “error theory” is the right description. I could definitely be wrong here, but I would have thought that nihilists would say something more like, “When properly regimented, sciences don’t quantify over (composite) objects, since there are no (composite) objects.” In that case, what counts as a literal reading seems to be up for grabs.

David Wallace’s example seems fine to me. I had in mind Elizabeth Spelke’s research on “Spelke objects” and the studies about when infants develop cognitive processes that allow them to perceive objects. Infants can’t recognize objects if they don’t exist!

So, yes, science gives us a reason to think objects exist. I don’t know that I would say the reason is “extra special”—but mundane reasons are reasons too. If you want to say that “properly regimented, sciences don’t quantify over (composite) objects” then you’re saying that Elizabeth Spelke is wrong in her claims about infant cognition, because her theory isn’t properly regimented. It looks like we have a disagreement between certain metaphysicians and scientists.

‘Infants can’t recognize objects if they don’t exist!’

Surely they could, in very much the same way that people can recognize a sense of having consciousness, even if (as per D Wallace’s view above) consciousness does not exist. Or in the way that people can recognize the passing of time, even if it may be that, as per a number of physicists and philosophers, time does not in fact pass. And so on.

“So, yes, science gives us a reason to think objects exist. I don’t know that I would say the reason is “extra special”—but mundane reasons are reasons too.”

Sure. But then there’s no reason to bring science into it. Here’s an easy argument against Nihilism about objects.

1. If Nihilism is true, then there are no chairs.

2. There are chairs. [I’m sitting in one right now!]

—-

3. Nihilism is not true.

I mean, great? I like that argument. I think it has true premisses and a true conclusion reached by a (basically) good inference rule. I’m not sure I find the argument *persuasive*, though. More accurate to say that I already rejected Nihilism and this is preaching to the choir. But presumably, the Nihilist thinks that such arguments are unsound, denying whatever goes in for the second premiss. What exactly is added by describing the second premiss (or some variation on it) as a scientific result? Seems to me that nothing is added and that describing things this way is very misleading. Whatever conflict there is between “silly” philosophical theories (such as Nihilism) and science is not on par with the conflict between science and the claim that the earth is flat or the claim that the earth is less than 10,000 years old.

If the ordinary case works against the Nihilist, then we don’t need to talk about sauropods or Spelke objects. Tables and chairs will do. We didn’t need *science* to get our conclusion, unless we are taking “science” in a very, very broad sense. Similarly, if tables and chairs aren’t sufficient, then sauropods and Spelke objects aren’t going to be more convincing. This is, I think, because neither cognitive science nor paleontology made a discovery that there are objects *in the relevant sense*. Rather, the paleontologist and the cognitive scientist borrowed (uncritically) an ordinary, everyday sense of “object.” It is in the ordinary everyday sense that a paleontologist might uncover a new sauropod. Or that cognitive scientists make discoveries about how we come to know things about tables and chairs. The Nihilist is no more running afoul of *science* in saying that there aren’t any sauropods (because there aren’t any composite objects at all) than I run afoul of science when I say that the sun rises in the east and sets in the west. And the Nihilist doesn’t have to say that Spelke (or anyone else) is making a mistake because there is no need to say that she is taking any position with respect to the metaphysical question. It’s not that she hasn’t regimented her theory properly, it’s that she hasn’t regimented it at all — and doesn’t need to in order to do the work she’s actually interested in doing.

By contrast, when a young earth creationist says that the earth is less than 10,000 years old, he really is running afoul of science, since the relevant sciences make claims about the age of the earth in exactly the relevant sense.

So that was undoubtedly a large derail, and as usual, I immediately regret my decision to say anything at all in one of these comments sections.

I guess I understand the practice of science as being continuous with common-sense observations such as “I’m sitting on a chair.” Shouldn’t we want there to be this continuity? If Spelke tells me about an occlusion study in which infants are surprised by the appearance of a new object from behind a screen, I should be able to replicate the experiment with my kids. “Oh look, my 6-month old is surprised.” Actually carrying out the experiment strikes me both as mundane (like noting the existence of tables and chairs) and as science.

I don’t disagree that there is some far stronger disagreement in the creationist sense. (One way to cash it out is that the creationist doesn’t think there is a reinterpretation or regimenting of palaeontology available). I didn’t intend to imply otherwise.

However, I think it is a mistake to assume that the notion of “object” in a given science is just the import – uncritical or otherwise – into that science of an everyday ontological category. (I could make that case in detail and depth for physics but I suspect something analogous is going on in other places.) A large part of the case for ontic structural realism in philosophy of science is based on the inadequacy of ordinary-usage-derived conceptions of ontology for scientific practice.

“However, I think it is a mistake to assume that the notion of “object” in a given science is just the import – uncritical or otherwise – into that science of an everyday ontological category.”

Just to be clear, I don’t want to affirm this either. I affirm only that the world of mundane, everyday observations is the same as the world of science, and there should be a continuity between both. Learning something in one entails consequences for the other. (I don’t think there’s a sharp boundary between the two.)

To engage in a bit of pedantry of my own:

It’s a matter of some controversy as to whether “Suaropods are herbivores” entails that some things are herbivores , as the latter seems to require a ontological commitment that the former does not (Think, “Unicorns are magical” and “Some things are magical”).

As to the relationship between science and commonsense objects, it seems Husserl was ahead of the curve with “The Crisis of European Sciences”.

Is Bas Van Fraassen’s anti-realism also suspect? And for similar reasons?

“Why think this? Various reasons, but mostly that otherwise there’s a slippery-slope argument, as Joshua Reagan’s comment suggests. Once we start deeming views so stupid that we can reject their adherents without first-order consideration of their scholarship, where do we stop?”

I think there are principled ways of avoiding the slippery slope. But rather than going into that I want to ask you whether you are really willing to hold that no views expressed by a candidate that are outside of their scholarship would be relevant to decisions about whether we ought to hire them. There are tougher examples than creationism. Perhaps an otherwise qualified candidate has publicly expressed the view that they belong to the master race and that all other races ought to be enslaved. Or perhaps they have defended pedophilia as an acceptable sexual practice that ought to be legalized. Would you not agree that the expression of these opinions would count against hiring them?

The position I’m advocating here is that it’s never okay in hiring to make inferences from people’s views on extracurricular topics to their academic competence at their own subject. (Not, “never epistemically warranted”, just “never okay in hiring”). From that point of view I think creationism is a much tougher example than the ones you give. (Pasqual Jordan was an outright supporter of the Nazi party, but also a world-class theoretical physicist.)

There is a separate argument as to whether someone’s normative views should ever be grounds to think that they will be an inappropriate colleague, or poor teacher, or just that some people are so morally bad that we should shun them. I haven’t here expressed an opinion on that matter. For what it’s worth, my view is “*at most* in the most extreme cases” (see my comments at http://dailynous.com/2015/01/28/students-protest-job-candidate-for-offensive-views/ ); I’m unsure about how to think about the extreme cases, but Conor Friedersdorf’s position at https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/08/fire-employees-white-supremacists/536877/ looks like a good starting point.

Fair enough. Substitute: “the sauropod found in dig X is a herbivore”.

Ceteris paribus, who would you rather hire:

1. An Aristotle scholar with an excellent publication record and a track record of inspirational teaching, but whom you suspect of being a republican evangelical; or,

2. An Aristotle scholar with a good writing sample and little to no publication record, about whom you have no suspicions of being a republican or evangelical

?

To be honest I wouldn’t want to hire an Aristotle scholar.

Quick Clarification: My earlier point was carelessly put and was predicated on thinking of fundamentalism not primarily as a collection of doctrines but rather as an adherence without evidence or argument to a set of beliefs (typically religiously based). I take that to be contrary to philosophical inquiry and if asked on a survey whether I would be more reluctant to hire a fundamentalist than a member of the ACLU, I’d be inclined to say yes. Of course, in any real hiring case one will have lots of evidence regarding philosophical competence and disposition and that would and should be, as some have said, determinative.

Please research the next info-bites better. This just poses more questions than are answered. And I think many are easy to answer, by looking at the book, which should have been done before writing / posting this.

Keep in mind that social desirability bias means these are probably lower bounds.

this cannot be emphasized enough. there’s a lot of psychological literature — especially that by dan ariely and also daniel kahneman — that shows how people do not know themselves very well and are often dishonest with themselves. while we’d hope philosophers are more honest, this isn’t even close to a guarantee unless we have good reason to believe otherwise. further, there’s lots of reasons to believe philosophers would have incentive to downplay this: stigmatization of bias and those who advance it, for example.

It looks like the context of this question was in a questionnaire ostensibly about collegiality and what it would be like to have people as a colleague, so that questions about whether one would feel more positive or negative about hiring someone would be thought of as collegiality questions more than hiring ones. This presumably mitigates the social desirability bias *slightly* (though of course only slightly).

I’m particularly fascinated, as a philosophy student and a member and leader of various Jewish communities, that these data indicate the least unwillingness to hire Jews of any religious group. There doesn’t seem to be an easy explanation for this phenomenon; my initial thought was that perhaps a smaller percentage of self-identifying Jews are theists than are self-identifying Christians or Muslims; explaining this phenomenon via an anti-theism bias seems inadequate, however, since more unwillingness was indicated to hire avowed atheists.

Perhaps, on a similar note, there is a belief among the professors surveyed that a Jew’s religion is less likely to impact their philosophical work than a Christian’s or Muslim’s is, and that stereotype wouldn’t be surprising (even though it’s harmful, to both Jews and Christians).

One thing I find fascinating is there is no anti-theist bias as such (given there is also a low % who don’t want to hire atheists, the same N as those who don’t want to hire Catholics or Muslims and higher than mainline protestants and Jews). Some theists do suffer bias (Mormons, Evangelicals), I wonder in how far this is because those hiring see these beliefs as proxies for other things, notably being politically conservative.

An interesting feature of this is that I suspect many liberal atheists, if pressed on whether they think the evidence is more strongly against the conjunction of typical conservative political views or against theism, will answer ‘theism obviously, and by a long way’. (Though I may just be overgeneralizing from my own case here.) If this is right, then it suggests that some of those who are wary of hiring theists but not conservatives are also more sure that the theists are wrong than that conservatives are.

I think we can all agree that the vast majority of philosophy professors are liberals and also democrats. This seems to fall in line with my personal experiences that liberals tend to be more intolerant than conservatives regarding ideas and opinions while conservatives are more intolerant towards people not similar to themselves. I’ve seen studies showing that liberals can be just as intolerant if not more so than conservatives. Here’s one by Pew showing that liberals are much more likely to unfriend than conservatives due to differences in political viewpoint.

https://www.cnsnews.com/news/article/ali-meyer/liberals-more-likely-unfriend-because-opposing-views-politics

There are other studies showing similar differences in intolerance .

https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/05/09/why-liberals-arent-as-tolerant-as-they-think-215114

It’s great to actually get some data about how dramatically conservatives are disfavored in academia. Of course, we all knew this anyway, but the documentation is useful.

I wonder whether there’s any traction to be had by broadening the du jour emphasis on diversity to include intellectual diversity as well: the academy is so starved for conservative voices that I’d reckon prioritizing hiring them would make a lot of sense.

I think you’re going too quick. If academics think that conservatives and Christians are more stupid, unreflective, anti-intellectual, etc. than non-conservatives and non-Christians, then it makes sense not to want to hire them. (Or Evangelicals, fundamentalists, or whatever.) Why pursue a form of diversity that includes those who are inferior for doing the sort of careful, thoughtful work that academics are supposed to do?

Sure, call this the “60,000,000 Americans are stupid” argument (i.e., Trump voters). Also call it, at many institutions, the “half my students are stupid” argument–more at land grant schools, fewer at private schools.

I’m not even sure how many problems there are with these arguments. For one, it shows little in the way of toleration, epistemic humility, etc., etc. For another, it’s a horrible marketing strategy for philosophy–or anything.

Alternatively, here’s a thought: don’t exclude conservative views from academia. If they’re stupid or pernicious, let the marketplace of ideas sort it out. Don’t alienate half of taxpayers or their families with liberal narcissism.

To be clear, I don’t hold that view. It seems to me, however, that something like this view is not uncommon in philosophy departments.

I’d like someone to model this to predict the consequences. Suppose every job committee has 5 members, with 1 member having an anti-Republican “bias” (or whatever word you want to to use) of strength p, with some decision rule to be specified, plus keeping in mind that people want to avoid acrimony and get the decision over with quickly, etc. What does this predict (on various plausible assumptions) about how many conservatives make it into academia?

Now add Schelling to the mix.

A couple important related pieces:

Timely, short, and snappy: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/bias-against-conservatives-works-like-any-other-prejudice/2018/04/10/17fa1838-3c40-11e8-974f-aacd97698cef_story.html?utm_term=.d06d1beb913e

A classic, long, and deep: http://slatestarcodex.com/2014/09/30/i-can-tolerate-anything-except-the-outgroup/

“A diversity of perspectives is necessary for vigorous and epistemically effective critical discourse. The social position or economic power of an individual or group in a community ought not to determine who or what perspectives are taken seriously in that community. Where consensus exists, it must be the result not just of the exercise of political or economic power, or of the exclusion of dissenting perspectives, but a result of critical dialogue in which all relevant perspectives are represented.”

—-Helen Longino, The Fate of Knowledge (p. 31)

Dave, I see that and that’s why we need to increase viewpoint diversity in philosophy (I think viewpoint diversity is important and that part of the heterodox academy I am on board with). But one issue for Longino’s view of scientific objectivity was that potentially – for the way she formulated it – that one would need the active cultivation of viewpoints that are anti-feminist. In the present case, what we are seeing is that conservatives tend to be less on board with a liberal arts education and conservative politicians are actively working to diminish the liberal arts in various places in the US. Insofar as conservative philosophers have those views, you might get the problematic situation that they’d help to cultivate views in the public sphere, potentially legitimize them, that would make the case for destroying the academic discipline of philosophy. I know that this dissatisfaction with liberal arts in conservative milieus is a relatively recent phenomenon and I don’t know in how far conservative philosophers take it into account, but it is a factor that might play a role.

Perhaps one reason for the recent surge in disdain for the humanities among conservatives (specifically Republicans) is that it becomes more and more obvious every day that humanities departments are illegitimately refusing to hire or take seriously conservatives and their views (as Yancey points out in the OP). And virtually anyone who has gone to college has had at least one (and probably many) professors who makes a habit of ridiculing conservatives with passing comments in lectures. So it’s clear to both conservative academics and conservative college students that humanities professors have contempt for them. If this diagnosis is correct, then the solution to the “republicans hate the humanities problem” is not to double down on shutting them out of the academy, but rather to bring them into the academy and stop pouring scorn on them.

It hardly seems disqualifying of a philosophical position that it has as a consequence that academic philosophy should end.

Hi Helen! (Imagine me waving hello.)

I’m not sure I see why Longino’s approach would require active cultivation of any viewpoints, as opposed to representation of viewpoints that are present already in the broader culture. E.g. if there are no Satanists in a given society, I don’t think you would need academics to become Satanists in order for that society to have a thriving academic culture on her view. But maybe I’m missing your meaning about actively cultivating viewpoints…

With regard to right-wing hatred of the liberal arts, I agree that that’s a big problem in broader US culture. I sort of doubt it could become much of a problem within the academy, though, for the reason of simple self-selection: conservatives who hate the liberal arts are probably unlikely to seek careers teaching the liberal arts. By analogy: progressives are culturally rather anti-military on average. I know some progressive members of the military, but I don’t know any progressives in the military who are politically anti-military.

I should add that I’m not necessarily on board with Longino’s overall picture, both insofar as some parts of it depend on her ontological pluralism (which I find implausible), but also (more importantly for present purposes) because I think she may be too sanguine about the effects of viewpoint diversity by itself. For example, I think it’s possible that viewpoint diversity within scientific disciplines might not be a panacea for political biases in the (social and biological) sciences. We might need more of a model of adversarial research, where *research groups* (not just departments) are composed of people who disagree with each other and who have to come to some agreement about what would count as a legitimate test of some controversial hypothesis. There have been a few examples of this in the social sciences, and I think it may provide a better model for how to escape the effects of bias than Longino’s democratically-constituted scientific community.

In the following paragraphs I quote from a relevant passage from Richard Rorty on the duty of liberal teachers to combat religious fundamentalism, from his “Universality and Truth”. Agreement with Rorty on the following is clearly sufficient to rule out hiring religious fundamentalists:

“It seems to me that the regulative idea that we—we…liberals, we heirs of the Enlightenment, we Socratists—most frequently use to criticize the conduct of various conversational partners is that of ‘needing education in order to outgrow their primitive fear, hatreds, and superstitions.’ This is the concept the victorious Allied armies used when they set about re-educating the citizens of occupied Germany and Japan. It is also the one which was used by American schoolteachers who had read Dewey and were concerned to get students to think ‘scientifically’ and ‘rationally’ about such matters as the origin of the species and sexual behavior (that is, to get them to read Darwin and Freud without disgust and incredulity). It is a concept which I, like most Americans who teach humanities or social science in colleges and universities, invoke when we try to arrange things so that students who enter as bigoted, homophobic, religious fundamentalists will leave college with views more like our own.

“What is the relation of this idea to the regulative idea of ‘reason’ which Putnam believes to be transcendent and which Habermas believes to be discoverable within the grammar of concepts ineliminable from our description of the making of assertions? The answer to that question depends upon how much the re-education of Nazis and fundamentalists has to do with merging interpretive horizons and how much with replacing such horizons. The fundamentalist parents of our fundamentalist students think that the entire “American liberal establishment” is engaged in a conspiracy. Had they read Habermas, these people would say that the typical communication situation in American college classrooms is no more herrschaftsfrei [domination free] than that in the Hitler Youth camps.

“These parents have a point. Their point is that we liberal teachers no more feel in a symmetrical communication situation when we talk with bigots than do kindergarten teachers talking with their students….When we American college teachers encounter religious fundamentalists, we do not consider the possibility of reformulating our own practices of justification so as to give more weight to the authority of the Christian scriptures. Instead, we do our best to convince these students of the benefits of secularization. We assign first-person accounts of growing up homosexual to our homophobic students for the same reasons that German schoolteachers in the postwar period assigned The Diary of Anne Frank.

“Putnam and Habermas can rejoin that we teachers do our best to be Socratic, to get our job of re-education, secularization, and liberalization done by conversational exchange. That is true up to a point, but what about assigning books like Black Boy, The Diary of Anne Frank, and Becoming a Man? The racist or fundamentalist parents of our students say that in a truly democratic society the students should not be forced to read books by such people—black people, Jewish people, homosexual people. They will protest that these books are being jammed down their children’s throats. I cannot see how to reply to this charge without saying something like ‘There are credentials for admission to our democratic society, credentials which we liberals have been making more stringent by doing our best to excommunicate racists, male chauvinists, homophobes, and the like. You have to be educated in order to be a citizen of our society, a participant in our conversation, someone with whom we can envisage merging our horizons. So we are going to go right on trying to discredit you in the eyes of your children, trying to strip your fundamentalist religious community of dignity, trying to make your views seem silly rather than discussable. We are not so inclusivist as to tolerate intolerance such as yours.'”

Josh: I’m curious as to what your argument contra Rorty is. Locke and Kant said similar things about the conditions necessary for liberal society to flourish.

1. If Christian fundamentalism is true, then liberalism (as Rorty understands it) takes students (and others under liberal rule) away from the truth.

2. Christian fundamentalism is true.

Therefore,

3. Liberalism (as Rorty understands it) takes students (and others under liberal rule) away from the truth.

I take 3 to count as a good reason to be opposed to liberalism (as Rorty understands it). Obviously a lot turns on whether Christian fundamentalism is true.

The liberal consensus protects the orthodox and fundamentalists as much if not more than it does everyone else. They are beyond foolish to oppose it.

As for fundamentalism, of all the versions of religion it is the *least* likely to be true. (And their truth is already highly unlikely, given their supernaturalism.)

Rorty says, “So we are going to go right on trying to discredit you in the eyes of your children, trying to strip your fundamentalist religious community of dignity, trying to make your views seem silly rather than discussable.”

Kaufman says, “The liberal consensus protects the orthodox and fundamentalists as much if not more than it does everyone else.”

Who should I trust? The guy who seems to describe accurately how liberal institutions are working to discredit and suppress the religious community of which I’m a member, or the guy who says that these institutions actually protect me while also apparently being in agreement with what the first guy said?

I have the sneaking suspicion you don’t have my best interests at heart.

Honestly, I could care less whom you trust. I’ve said what I think on the subject. If you want to just keep on losing, socially and culturally, in modern society, go right ahead.

This is exactly why you don’t understand my point of view. I’m not trying to “win, socially and culturally, in modern society.” I’m trying to fulfill my duty to God and be vindicated in eternity.

Obviously prudential concerns are still important, but when the liberal deal is “we’ll try to crush your community over time, but peacefully, not violently” then you really shouldn’t get so upset that I’m not all that impressed with it.

To add to my previous response (since there is no edit function), not too long ago, I actually did a short piece on why the orthodox have the most to lose from the abandonment of the liberal consensus.

https://theelectricagora.com/2018/03/10/the-liberal-consensus-and-the-orthodox-mind/

I’m more with Putnam and Habermas on this issue, than with Rorty. But in his defense, consider this argument that seems parallel to yours above:

1. If we are brains-in-vats, then promoting the empirical sciences leads students away from the truth.

2. We’re brains-in-vats.

—

3. Promoting the empirical sciences leads students away from the truth.

It’s not just the truth of 2 that is at issue, but its reasonableness. Do you think it would be irresponsible for, say, a chemistry professor to ignore completely a discussion of whether we are BIVs? True, she may be leading her students astray on a daily basis. But the evidence that we are BIVs is so weak, and the evidence for the truth (or at least efficacy) of the empirical sciences is so strong, that she seems fully justified in just teaching chemistry. Of course, in a liberal society, anyone can carry on being an BIVer. But science professors shouldn’t waste their time dealing with those views, take them seriously, or portray them as anything other than silly. Christian Fundamentalism is probably more plausible than the BIV proposition, but only just – though I do wonder whether either is falsifiable in the minds of their defenders.

I concede that if you think my religion is wildly implausible, the argument I gave isn’t much help. The point of the argument wasn’t to convince skeptics, but to show why I might disagree with Rorty. (Naturally I don’t think my religious beliefs are wildly implausible.)

By the way, I’m not sure I agree with how you characterize Locke. By contemporary standards wouldn’t he be considered relatively fundamentalist? If I recall correctly he was quite conservative in ascribing a great deal of epistemic authority to the Christian Scriptures. I know he defends religious liberty, but it’s a long way from that to what Rorty is saying in this passage.

Locke is no fundamentalist, unless you are using the term with a bizarre connotation.

If you read the Letter Concerning Toleration, he certainly argues that certain brands of religion are less compatible with liberal society than others.

I’m aware he didn’t believe in extending toleration to committed Roman Catholics. This seems to me to have more to do with his opposition to the royalist/high-church faction in the English Civil War than it does to being largely in agreement with Rorty on this topic. I can’t imagine him saying anything like what Rorty does above, because he seems to be a very committed low-church (and idiosyncratic) Christian who took the Bible pretty literally, as far as I’m aware. I have little doubt about what Rorty would want to do with any student holding such views.

I should be clearer— the conflict between the high-church/royalist/cavaliers and the low-church/parliamentarian/round-heads was not limited to the English Civil war, but lasted throughout the 17th century until the former were defeated fairly definitively in the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688. Locke had well-known sympathies for the latter faction.

(He was also opposed to toleration for atheists, a fact I didn’t know until a few minutes ago.)

There was no such thing as Christian fundamentalism before the late 19th century. Fundamentalism is a reaction to theological modernism. Christian fundamentalists maintain that one must hold a fairly long list of beliefs to count as a true Christian (including beliefs in the literal truth of Biblical accounts of creation and of Christ’s miracles), and that theological modernists are not true Christians.

All fundamentalists are theological conservatives, but not all theological conservatives are fundamentalists. Consider someone who believes that the story of creation in Genesis is literally true, but that one can believe in evolution and still count as a Christian. This person is a theological conservative (at least on one point) but not a fundamentalist.

Was Locke a theological conservative? The Stanford Encyclopedia article on Locke says that Locke claimed to be a faithful Anglican but may have held some unorthodox beliefs. He encouraged Isaac Newton to publish an anti-Trinitarian tract. That isn’t proof that Locke himself rejected the Trinity, but he was clearly open to theological debates.

Your first paragraph is spot-on and the reason why I had the feeling Josh was using the term ‘fundamentalist’ in a way at odds with common usage.

The rest of your observations on Locke are also correct. Thank you.

Pedantry.

Well then, I’m sure that if John Locke applied for job at a philosophy department, the 54% of survey respondents who don’t want to hire fundamentalists would have no problem giving him a job! They would surely have no problem with his arguments from Scripture; for example his argument from Judges 11 that the people have a right to “appeal to heaven” in the event earthly authorities aren’t giving them justice.

I’m using the term “fundamentalist” a bit loosely, as are, I presume, most of that 54%. By the way, your claim here:

“Consider someone who believes that the story of creation in Genesis is literally true, but that one can believe in evolution and still count as a Christian. This person is a theological conservative (at least on one point) but not a fundamentalist.”

This is far more restrictive about who counts as a fundamentalist than anything else I’ve ever read, which includes many of the essays in the famous collection of essays whose title inspired the original use of the term “fundamentalist”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Fundamentals.

Allow me to save all of us some trouble:

“I was obnoxious and rude to another respondent. It was uncalled for and I apologize to everyone here for my behavior, including Justin.” – Joshua Reagan, April 2, 2018

(This is in reply to “Pedantry” above. Nesting isn’t working up there.)

My charge of “pedantry” is to highlight the fact that Kaufman is making a trivial objection regarding a minor terminological matter to ignore my substantive claim. My response is legitimate, and I don’t think I’m out of line to point it out.

First of all, according to the (idiosyncratic) definition of “fundamentalism” offered by Untenured Ethicist, there is no such thing as an Islamic fundamentalist, because “fundamentalism” in the strictest sense of the term is a Protestant Christian movement. This is not the standard use of the term either in the public at large, or among philosophers. Usually the term is applied to those whose religious views are particularly conservative and perhaps somehow reactionary in character.

Second, in John Locke’s day, his low-church Protestantism admittedly wasn’t reactionary, and could probably be construed as left-of-center. Nevertheless, if we transported him to the 21st century his high view of Scriptural authority and his view that religious toleration should not extend to Roman Catholics or atheists would make him resemble modern day fundamentalist Southern Baptists a lot more than it would make him resemble Richard Rorty. This is why I qualified my claim in two ways: (i) “relatively fundamentalist”, and (ii) “by contemporary standards.”

Third, arguably the early settlers of Massachusetts imposed a notion of religious tolerance that seems to align with Locke’s views, at least as I understand them (http://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass07.asp):

“Wee doe by these presents for vs Our heires and Successors Grant Establish and Ordaine that for ever hereafter there shall be a liberty of Conscience allowed in the Worshipp of God to all Christians (Except Papists) Inhabiting or which shall Inhabit or be Resident within our said Province or Territory…”

Yet 17th-century Puritan Massachusetts was probably the closest thing to a Christian theocracy we’ve ever had on the North American continent. Puritans were, by the way, a large part of the Parliamentary coalition that John Locke supported in the English conflicts of the 17th century. These weren’t his enemies.

I’m no Locke scholar, but everything I have seen seems to indicate that this is a man who was deeply committed to a low-church Protestant polity that is drastically different from the one offered by Richard Rorty above. That’s my point. To get hung up on whether or not that makes him “relatively fundamentalist by contemporary standards” seems to be a pedantic way for others to avoid having to concede my point, especially when according to any but the most stringent definition of “fundamentalism” the claim seems right.

Of course other religions have fundamentalist movements. They have the same structure: fundamentalism is always a reaction to modernism. It is not the same as orthodoxy or theological conservatism.

This is the way my college Bible professor, Rev. Peter Gomes, defined fundamentalism. It is also how Wikipedia characterizes fundamentalist movements. Wikipedia may not always be a reliable source, but it’s a fairly reliable indicator of what uses of a word are widely recognized.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamentalism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_fundamentalism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_fundamentalism#Origins

In the survey cited above, the philosophers polled were more reluctant to hire fundamentalists than they were to hire evangelicals. This difference in attitudes makes sense, given (what I take to be) the standard definition of fundamentalism. Fundamentalists are by definition at least somewhat intolerant of other religious beliefs, in a way that conservative or orthodox religious believers of other sorts are not. Tolerating the intolerant is sometimes the right thing to do, but it isn’t easy.

Your (Joshua Regan’s) clarification that you are not using the word “fundamentalism” in this way is helpful. It might be helpful to avoid using the word “fundamentalist” to describe your religious beliefs to others. You may be sending signals that you do not intend to send.

I don’t know Rorty’s work well, but I suspect that when he writes about educating fundamentalists, he is concerned specifically with intolerant fundamentalists, not with the larger group of people who have conservative theological views.

Your revised definition of “fundamentalism” strikes me as more reasonable and closer to the common use of the word.

The definition of fundamentalism I was using comes from George Marsden’s book Fundamentalism and American Culture (p. 4): “a loose, diverse, and changing federation of co-belligerents united by their fierce opposition to modernist attempts to bring Christianity into line with modern thought.” This describes my views tolerably well, depending on what counts as “modern thought”, and so I consider myself a fundamentalist. Certainly I am skeptical about the some aspects of the liberal project—particularly as it relates to religion—in a way that puts me out of step with typical conservatives today. I’m not a Rorty expert either, but I’ve read enough to feel pretty confident that when he says “fundamentalist” he means people like me.

Obviously John Locke wasn’t a fundamentalist in the strictest sense because he wasn’t reacting against modernity; he was a fore-father of it. Even so, his actual theological beliefs have more in common with modern day fundamentalists than they do with Rorty, which was all I was trying to say. You mention intolerance of other religions. Locke was intolerant of Roman Catholicism (and atheism, which it seems to me would probably also count as intolerant by modern standards). I didn’t (and wouldn’t) claim that Locke was orthodox, because the evidence seems to suggest he had, at least at times, Unitarian sympathies.

If you’re still here, George:

Thanks!

What percentage of the sample was more willing to hire people from these groups?

If more people in the sample are ”more willing” to hire people from some/all of these groups, then the net effects of those who are ”less willing to hire” particular groups could be canceled out (or outweighed) by more people being more willing to hire these people.

(Obviously, that doesn’t quell the worry that individuals can be less willing to hire people from certain groups. But it could diminish the worry that committees would, overall, be less willing to hire people from these groups. I imagine that George covers this in the book. If so, it’d be great to be pointed that part of the book.)

According to the data in the book, for most groups and most disciplines the large majority of those surveyed in that discipline did not indicate more willingness to hire people from that group. For example, within philosophy, .7% said they were more willing to hire a Republican, 2.0% to hire an NRA member, and 4.6% to hire an ACLU member.

Thanks Nevin (and George!). That is helpful clarification.

Nevin hits it on the head. There was a much stronger propensity to be unwilling to hire than willing to hire.

The data is about academic philosophers in the US and not about academic philosophers more generally. One cannot generalize beyond the US with such data because the culture of academia can differ significantly from country to country and there are certainly significant differences between the US, UK, Western Continental Europe, Eastern Europe, Australia & New Zealand, and Asia. Furthermore, at least half the categories that participants were asked to consider are US-centric and not very applicable to other countries. Therefore, could commentators please use the term “US-based academic philosophers” rather than “academic philosophers” when discussing these survey result as the latter grossly overgeneralizes. It may feel to some that US academia is the center of the world and that academia elsewhere always follows in its footsteps, however, that is not true. Academia is in a much healthier condition in many other parts of the world and as the US continues to decline in the coming decades, relinquishing its position as a global superpower and dominant cultural force, academia elsewhere will become more influential and more important.

I’m surprised that people answered honestly (insofar as they did; kudos to Brennan’s comment above) about not wanting to hire anyone LGBT.

They weren’t asked to say that they didn’t want to hire anyone LGBT. They were asked (in the middle of a series of questions about collegiality and how you would feel about sharing a department with various people) whether some of these categories might make them feel less positively inclined towards hiring the person.

I’ve been on search committees where having even a presentation on, say, Ayn Rand, let alone a publication, was deemed by the majority sufficient to trash the application. I’ve been on search committees where members were explicit that they didn’t want someone who took their Christianity to be central to their identity, even if they didn’t write on topics where it would seem relevant. I’ve been on search committees where members are initially enthusiastic about a candidate, but, after googling and finding out the candidate’s political leanings, came up with all sorts of excuses, some of which they previously argued against, to not move them on to the next stage. All anecdotal, of course. But the survey results don’t surprise me at all. I suspect the numbers are actually higher, given that people often answer surveys in ways that reflect the answers they think they ought to give.

George, I am wondering why you chose the groups you chose to study. HR reps and AA officers, and hence search committees, have access to data about race, sex, disability, age, criminal history, and veteran status, because that is asked for on applications. In general they do not have access to data about religion or sexual orientation unless it is clearly signaled from a CV in some strange way.

For the data to tell us about hiring practices we would want to know what philosophers think about those categories that they have access to.

The data represented above tell us about hypotheticals that search committees are not likely to encounter. (Would anyone put “lifetime NRA member” on a CV?)

Has a study been conducted to test for those categories that HR software typically asks for, to see if any of the groups you studied are stand-ins for your categories?

(As a side note, not that I’ve ever come across this, but if veterans are perceived as conservative, which I believe they are, are they being done a definite disservice when asked to self-identify to a hiring committee?)

Philosophers who work on topics related to their religion or their sexual orientation typically disclose this information on their CV via paper titles.

I choose not to focus on categories that I thought would not have a lot of variability in them. I do not think a lot of academic would admit to be less willing to hire a black, for example, even if that was not the case. And you are correct that these are groups that normally we may not know if a candidate is a member of them but it still matters. If you are an NRA member as opposed to an ACLU member then you have more of a burden of hiding that membership during your campus visit. I also think that the data has implications beyond the hiring stage. If you are an NRA member will that factor into you getting tenure, getting promoted, getting a grant. There are reasons, beyond this particular study to think that it may. But for this one I concentrated on obtaining a position.

“In general they do not have access to data about religion or sexual orientation unless it is clearly signaled from a CV in some strange way.”

If you are trans, this is very likely to come out on your CV. You may, for example, have published under a different first name, or gone to an all-[gender] college different from your current gender, or any number of little things. Since anti-trans discrimination is one of the more alarmingly high percentages in the results, this is not an idle concern.

Isn’t it relatively rare to know of a candidate which of these categories they fall into, at least for most of the categories?

David Sobel – well knowledge might be a strong term. But I do not think it is rare to have strong beliefs about this. Especially with the internet and social media, the names of presentations, people who have sponsored a philosopher’s work, etc. Alas, I think often these beliefs are false. I know several progressive, atheist, philosophers, who have taken research money from libertarian and Christian organizations (they think it is better that they have the money than others) and then are falsely labeled religious or libertarian.

I remember a discussion a few years back over at Leiter about how certain (probably) Christian colleges felt it well within their rights not to hire homosexuals, Christians of other denominations, Muslims, atheists, etc. I remember when I was on the market many years ago many positions that said: must sign declaration to be x or y. Without reading the book (forgive me), it seems Yancy is measuring the personal biases of people at (I’m guessing) state or large non-denominational (or not seriously denominational) schools. There exist, after all, many schools (how many I don’t know)–some of them fundamentalist–that have explicit institutional rules against hiring people who fit many of the categories above. These same schools have (or have had) explicit prohibitions against teaching certain subjects (like evolution) I wonder how that figures in the data.

The difference between slight and strong unwillingness strikes me as being potentially very important. Admitting to a strong unwillingness to hire a member of a certain category seems rather bold, as if the person is unashamed of this prejudice and might well act on it. Admitting to a slight unwillingness could be evidence of just as strong a prejudice plus dishonesty about it, but it could also indicate a merely imagined, or at least extremely slight, prejudice plus a stereotypical ‘bleeding heart’ desire to own up to one’s faults. The latter kind of person might be very unlikely to act on their perceived prejudice, and might even go out of their way to act against it.

To know whether the preferences at issue are likely to affect hiring, then, it seems we really need to know not only how likely search committees are to know whether an applicant belongs in any of these categories, as noted above, but also whether their unwillingness is strong (which would be worrying) or only slight (which might not do any harm at all).

Within limits, I care more about someone’s reasons for their views than I do about the content of those views. I’d be more interested in working with someone with good arguments for unlimited gun rights or trickle down economics or the incarnation or young earth creationism than I would be working with someone with merely dogmatic adherence to the “right” views.

I’d also be fine having a colleague who earnestly and with some intellectual rigor defended unlimited gun rights or trickle down economics even though I suspect that any argument they came up with would be ultimately flawed in some way. However, there is no intellectual rigor (or ‘good arguments’ as you put it) when it comes to young earth creationism and I’d rather have a dogmatic colleague with the “right” views than one of those [unkind word omitted].

Maybe not but I would at least be willing to hear someone out before deciding not to hire her.

So, a couple points worth making.

First, independent of what you think philosophically, discriminatory hiring on the basis of religious belief is, with very few exceptions, explicitly prohibited by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. It’s frankly rather alarming, in that light, to see so many comments arguing for the legitimacy of discriminating directly against “fundamentalists” in hiring decisions.

Second, some commenters are suggesting that disbelief in widely supported scientific facts provides at least strong defeasible evidence of philosophical competence. As counterexamples, I offer Arthur Prior and Peter Geach (who rejected the theory of relativity), Jerry Fodor (who was famously sceptical of Darwinist evolutionary biology), and Wilfrid Sellars (who took it he could refute quantum mechanics from the armchair). To think that these rejections give us even prima facie justification for dismissing their philosophical contributions strikes me as absurd. (Indeed, it may well be argued that their deviance from scientific consensus was of philosophical benefit: had Prior not been the sort to flat-footedly reject STR, we might well not have gotten his brilliant work in tense logic or his lucid work in the philosophy of time.)

Finally, on an entirely separate note, as a trans philosopher I am shocked and appalled by the fact that a full fifth of the respondents would consider turning me down on that basis. This ought to be a source of shame for the profession.

(Moderators: please disregard already submitted version of this post, and thank you for keeping the comment section clean!)

“First, independent of what you think philosophically, discriminatory hiring on the basis of religious belief is, with very few exceptions, explicitly prohibited by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. It’s frankly rather alarming, in that light, to see so many comments arguing for the legitimacy of discriminating directly against “fundamentalists” in hiring decisions.”

There is no morally significant difference between religion and other monolithic belief systems, such as communism, that people adhere to. If discriminatory hiring on the basis of disreputable religious beliefs should be prohibited than discriminatory hiring on the basis of endorsement of communism should also be prohibited. It’s not clear to me that either should be prohibited so I am interested in having a debate on this question. If Title VII of the Civil Rights Act grants a special status to religions but not to other monolithic belief systems then it is a flawed and immoral piece of legislation.

Your frank and unconcealed indifference to complying with the bedrock of American civil rights law is, at least, refreshingly straightforward.

As for the propriety of designating religion a protected class, this seems a matter better settled by the federal judiciary and our elected legislators than a bunch of commenters on a philosophy blog.

These results and this comment thread are terrifying. I hope it motivates US universities and colleges, both public and private, to make sure that hiring committees understand that it is in fact illegal to violate US federal civil rights law. My personal experience is such that graduate students who participate in the hiring process are especially in need of this guidance. I’ve noticed that most faculty members on hiring committees at least understand the content of the pertinent law and make efforts to avoid the appearance of having violated said law. I would also like to point out, based also upon personal experience, that rejecting applicants on the basis of religion can easily become a proxy for rejecting applicants on the basis of race, in case anyone is in favor of violating US federal civil rights law on the former, but not the latter point. My hope is that schools’ fears of being exposed to extraordinary legal liabilities will keep these hiring committees in check. Freedom of religion is not only the bedrock of US federal civil rights law, it is also the bedrock of the US Constitution.

I am shocked and disappointed about the results for ‘transgender’.

I’m not shocked, and am no longer so naive as to be disappointed anymore. (Don’t you know the real and only problem with these results is that there seems to be some discrimination against people who think that those who are trans are, simply in virtue of this somehow, sinful/unnatural, deceitful, or mentally ill? Or that we’d all be better off if people would stop trying to push their wacky illiberal trans-ethics on the rest of the profession sans any argument, rigour, and reasons? Or that clearly these people have somehow, despite not having any arguments, have come to takeover the humanities? Or…)

Are there and grounds for doubting these results? I’m abolutely astonished by them. If they really reflect what is going on in philosophy, we have a lot of work to do addressing such bias.

In case people are assuming that philosophers would not be less willing to hire philosophers of their own group, I mention the following experiences.

Multiple Christian philosophers (some would have called themselves evangelicals at some point) have told me that they look down on Christian philosophers’ work when it seems to be motivated by the philosopher’s evangelical commitments. For instance, one said that doing philosophy in a way that allows their Christian beliefs/priors to play a role in their philosophy is just bad philosophy.

I am not endorsing this view. I mention it only to point out that it is not only non-X philosophers who would every be less willing to hire X philosophers — e.g., that only atheist philosophers would be less willing to hire an evangelical philosopher. My experience suggests that philosophers from a particular group will openly admit that they are less willing to hire philosophers of their own group, depending on the nature of such philosophers’ work.