Ethics Announces New Editors and Gender Data

The well-known and highly-regarded academic philosophy journal, Ethics, has announced its new editors.

At the end of June, 2018, Georgetown University professor of philosophy Henry S. Richardson will be stepping down from his 10-year tenure as editor (in chief) of the journal. On July 1st, Julia Driver, professor of philosophy at Washington University in St. Louis, and Connie Rosati, professor of philosophy at the University of Arizona, will become the journal’s co-editors (in chief).

Professors Driver and Rosati are currently associate editors at Ethics.

In a statement about the change of editors, Professor Richardson says that “one of the things that they would like to do is to redouble the journal’s efforts to attract work by female authors and authors of color.” To that end, he writes,

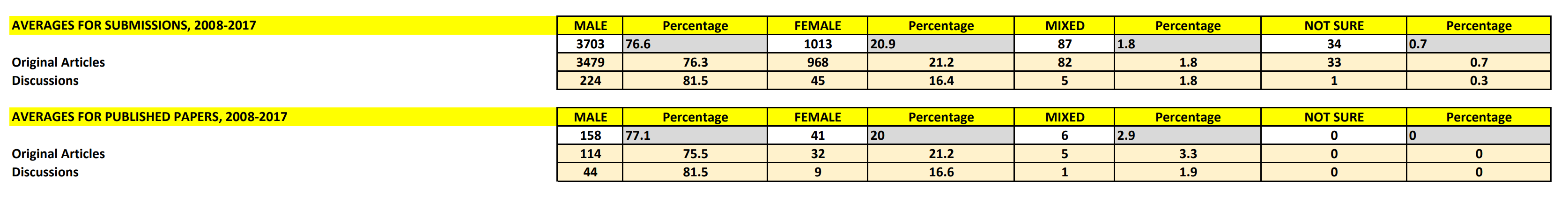

I am implementing two steps designed indirectly to aid the cause of reducing gender imbalance in philosophy publishing. First, to increase transparency and general understanding, I here publish for the first time the statistics that we have been collecting, for our internal use, on the genders of our submitting authors and those of the authors whose papers we end up publishing. The second step is to improve the quality of this data so as to facilitate analyses using it. Our determinations of authors’ genders have hitherto rested mainly on first names, occasionally supplemented by internet searches. We have added a required field in which each submitting author will be asked to indicate their gender however they like. By not imposing a list of categories, we will avoid forcing anyone to choose among options none of which they accept and will collect, over time, a set of data that, I am told, will not only be more accurate than what we have been gathering but will also allow for answering the broadest range of queries. Because none of our editors ever sees personal information about any paper’s authors until after the final decision—irrevocable rejection or acceptance—has been reached, it should not alarm anyone that we are collecting such data. Anyone who objects to offering any substantive answer to the gender question is free to answer “not applicable.”

The statistics show that while about three-quarters of the submissions to the journal over the past ten years have been authored by men, there has been a modest increase during this time in submissions by women. Further, the gender breakdown on submissions, averaged over the past ten years, is very close to the gender breakdown on published papers during that time.

The rest of the statistics begin on page three of this document.

Collecting and distributing more and better data on gender in their publication pipeline is a great service to the scholars working in this field, and Ethics should be commended for doing so. I think their other steps deserve more careful justification if they are to be officially adopted by a top ethics journal.

Consider the proposal to admit more articles from feminist ethics in order to increase the gender ratio of published articles. Under the form:

1. A higher proportion of female authors in Ethics is inherently good;

2. Admitting more articles from feminist ethics is likely to increase the proportion of female authors in Ethics;

Therefore, admitting more articles from feminist ethics is likely to lead to good results.

This argument is valid, but the normative premise is contestable and would need much more justification to be defended.

Contrast this argument with the following argument:

1. It is good to have the highest quality articles in Ethics possible;

2. Gender bias decreases the quality of the articles in Ethics;

Therefore, decreasing gender bias is a worthy goal of the journal Ethics.

In contrast to above, this argument seems unquestionably sound, and the normative premise is unimpeachable.

These arguments should not be conflated. If we believe the second argument, but we do not believe the first, then defending the inclusion of feminist ethics on these grounds is much more difficult to defend. A possible argument would be:

1. It is good to have the highest quality articles in Ethics possible;

2. The relative paucity of feminist ethics in recent publications of Ethics is evidence of gender bias;

3. Gender bias that omits feminist ethics from Ethics decreases the quality of the articles in Ethics;

Therefore admitting more articles from feminist ethics is good.

This argument is more difficult to defend and more controversial because the truth of the second and third premises is controversial even if all sides accept the normative premise. If Ethics is going to change the content of its publications on this basis, it seems they need a more detailed justification.

Neither of the arguments you have provided is valid. If you are going to call an argument ‘valid’ or ‘sound’ in a public forum, please ensure that it actually is valid (and that you have a firm grasp of what validity is).

The great part about logical argument is that you can point to errors in the argument specifically, rather than engaging in ad hominem attacks. I have no doubt that all of my arguments could be improved upon. I presented them to draw a distinction and call for more specific justification. If you care to show why they do not meet that task because of invalidity, that certainly wouldn’t offend me; it would be a great service.

I *did* point to an error in the arguments: I pointed out that the arguments are not valid. I was not aware that I would have to explain what validity is. The ad hominem was *in addition* to the criticism of the validity of the arguments.

Formal validity is the property that an argument has iff its logical form is such that necessarily, if its premises are true, then its conclusion is true. So in order to evaluate validity, we must determine what the logical form of the argument is.

Consider argument #1. As far as I can tell, it is the closest one of the 3 to actually being formally valid. Unfortunately, as its premises are currently written, there is no adequate way of formalizing all of them in sentential or quantificational terms that renders it valid.

For example, the premise “A higher proportion of female authors in Ethics is inherently good,” *might* be adequately translated quantificationally as (x)((Female(x)–>(y)(Paper(y))Authored(x,y))–>Good(y). Or “Any female-authored paper in Ethics is a good paper.” But surely this is not what that premise purports to say. That premise does not suggest that female-authored *papers* in Ethics are inherently good, it merely suggests *that it is good that* there be female-authored papers in Ethics. So, as best that I can make sense of that premise, it has no adequate quantificational form. Let me therefore formalize premise 1 as:

1. G (for ‘good that…’)

Premise #2, “Admitting more articles from feminist ethics is likely to increase the proportion of female authors in Ethics” also has no adequate formal translation in quantificational terms. For the following terms in this sentence: ‘likely’, ‘increase’, ‘proportion’ prevent any adequate translation. I suspect that the best translation of Premise 2 is actually:

2. L (for ‘likely to…’)

But I can be a bit more charitable than that. Suppose we invent a new connective, ‘>%–>’ to stand for ‘…likely to increase…’. And suppose we add that ‘A >%–> B’ is true in all the same models that ‘A –> B’ is true in. Then, Premise 2 *might* be formalizable as:

2. F >%–> A (for something like, ‘(Feminist ethics papers are admitted to Ethics) >%–> (There are female authors of papers in Ethics)’.)

Lastly, the conclusion of the argument contains terms that literally make no appearance in either Premise 1 or Premise 2. Here I have in mind the inclusion both of ‘likely to lead to’, which is *not* identical to the connective, ‘likely to increase’, found in Premise 2. Likewise, ‘good results’ is *not* identical to the phrase found in Premise 1, ‘is inherently good’. If they had been identical, then maybe with some careful rewording, Premise 1 and Premise 3 (the conclusion) may have some hope regarding an adequate formalization. But they are not. So that is a major obstacle to formal translation.

Even if we read ‘likely to lead to’ as if it said ‘likely to increase’, we get something like this formalization:

3. F >%–> R (for something like, ‘(Feminist ethics papers are admitted to Ethics) >%–> (There are good results)’.)

Hence, at the end of things, the best sense that I can make sense of this argument is that it has something like the following logical form:

1. G

2. F >%–> A

3. Therefore, F >%–> R.

Assuming that >%–> has the same truth-table as –>, this gets us:

1. G

2. F –> A

3. Therefore, F –> R.

This is not formally valid. It is false in at least one assignment of truth-values to G, F, A, and R.

If you are going to call an argument valid in a public space, please ensure that it actually is valid. Please, at the very least, carefully check your phrasing of the argument in natural language to ensure that it is valid when formalized.

This is to say nothing of Arguments 2 or 3. I have carefully examined those two, and I have no hope that they even resemble a formally valid argument.

This is interesting stuff, thank you. I agree with most of your critiques in a formal sense. I took some liberties with the language to try to limit how glib it came off, and I did not expect that using the language of validity and soundness would be so grating. Perhaps I won’t use it again in this context.

That said, as I indicated above, the purpose of presenting the arguments was to draw a distinction in families of arguments and call for a more detailed justification.

LLM: If your formalizations cant render the following sort of argument valid, then so much for the quality of your toolkit of formal tools. I would have thought this was pretty obvious. I leave it to others to figure out what formal tool, exactly, is appropriate.

A is likely to lead to increase the value of x.

A higher value of x is something good.

A is likely to lead to something good.

Consider the following, which is a much closer match to the form of IGS’s first argument:

1) A reduction in human suffering is inherently good.

2) The prevention of any future human births is likely to lead to a reduction in human suffering.

Therefore, 3) The prevention of any future human births is likely to lead to good results.

I would also like to echo LLM’s point that philosophers should avoid calling an argument valid or sound, unless it is in fact valid or sound. These are technical terms, not synonyms for “pretty convincing”.

So the objection is to the substitution of “something inherently good” with “good results”. Sorry, but that seems like pretty weak sauce. Validity is a property of arguments and arguments are made out of statements, not sentence tokens. Its acceptable to construe an argument as valid if you think two bits of natural language contribute the same content to two of the statements in the argument *as it is written out in english* *in context*. If in context, those expressions contribute the same content, then the argument is valid. if not, it isnt. you can’t just beg the question by repeating the bits of language in a different context.

This is a valid argument:

John has a bank

banks contain money

—-

john has something that contains money

and this one isn’t

The Mississippi has a bank

banks contain money

therefore the mississippi contains money

in the first case context shows that the word “bank” is contributing the same content to the first premise as it is to the second. In the second case, this is not true.

you can’t show that an argument is invalid by repeating the same form with the same bits of natural language (where the conclusion doesn’t follow from the presmises) without also showing that the context shift hasn’t altered the meaning of the words. I think that’s what you’ve done here. But this is all complete nonsense. There is a simple charitable reading of the bit of text that was provided that makes it a valid argument, and everyone in this thread knows it.

grrrr. I meant to write “Therefore, the Mississippi has something that contains money,” obviously.

I’m unable to reply to your next comment for some reason, so I put it here instead:

“you can’t show that an argument is invalid by repeating the same form with the same bits of natural language (where the conclusion doesn’t follow from the presmises) without also showing that the context shift hasn’t altered the meaning of the words.”

I don’t think that the context shift in my argument does change the meaning of the words in a problematic way. If you do think this has occurred, I would appreciate your pointing out exactly where the change of meaning is.

I also don’t see an obvious charitable reading of IGS’s first argument that would make it both valid and normatively significant. My paraphrase of the argument was intended to reveal a problem. That problem is that while a certain course of action may be likely to lead to results involving an inherently good feature (a higher proportion of female authors in Ethics/a reduction in human suffering), those results may still be all things considered bad, and so it may not be likely that the action will lead to good results. This may occur because other likely results of the action are bad.

In this case, it may be that even though it would be good for there to be a higher proportion of female authors in Ethics, the proposed method of achieving this would have bad effects. For example, there will be bad effects if any of the following are true (I assume, with IGS, that the higher the quality of articles in Ethics, the better).

1) Articles in feminist ethics tend to be of poorer quality than articles in other areas.

2) Although articles in feminist ethics tend to be of roughly the same quality as articles in other areas, the papers which would be admitted given a preference for feminist ethics, but which would not be admitted without this preference, would be of a poorer quality than those articles which would otherwise be admitted from other areas.

3) Admitting more articles from feminist ethics would be unfair to those authors (including women) who work in other areas of ethics, and this unfairness would be a significantly bad feature.

4) Although it would be good for there to be a higher proportion of female authors in ethics, it would be bad for this to be achieved by introducing a significant discrepancy between the proportion of male-authored articles which are accepted and the proportion of female-authored articles which are accepted; and the proposed method would have this effect.

My point is not to defend any of these claims. I’m just pointing out that their truth would undermine IGS’s conclusion, even if all the premises in IGS’s first argument were true. This would not happen if the argument were indeed valid.

While I agree it was poorly worded, the point of putting forward Argument 1 was to suggest that it was insufficient because its normative premise does not include competing normative factors such as those suggested in Tomi’s last comment. Dealing with these considerations is what I had in mind when I suggested it would “need much more justification to be defended.”

The software only lets “reply” recurse so many times.

Isn’t the point here obvious though? If someone tell you they are presenting a deductive argument, and they change the wording a phrase that is distributed into two premises, or between a premise and the conclusion, then the principle of charity says that, if possible, you should interpret the two phrases the same way.

you seem to be suggesting that there’s no way to do that. but I don’t understand why you don’t think it could be read to mean this:

1. A higher proportion of female authors in Ethics is a good thing.

2. Admitting more articles from feminist ethics is likely to increase the proportion of female authors in Ethics;

Therefore, admitting more articles from feminist ethics is likely to lead to a good thing.

you are of course right that the good thing it will lead to might be (*trigger warning*) trumped. But all that needs to be done is to interpret the conclusion so that it is consistent with that.

Also, this normative premise is ‘unimpeachable’?

“It is good to have the highest quality articles in Ethics possible”

I imagine that we could greatly increase the quality of the articles published in Ethics by kidnapping all living ethicists, putting them into tiny prison cells, and forcing them to spend all their time on activities that will make their writings better. We could motivate them with threats of torture, or perhaps rewards (we will have to see what works best). In short, it seems quite possible that the way to produce ‘the highest quality articles in Ethics possible’ involves horrendous, immoral actions. So the premise is likely to be false–and is certainly not unimpeachable!

1. good ≠ choiceworthy all things considered

2. As an adjunct moral philosopher, this is weirdly close to my life! (And it’s not so bad!)

I don’t think I need to interpret good as ‘choice worthy all things considered’ in order to declare that enslaving all living ethicists is not good.

Also, my reply was meant to be humorous. Not die-laughing-humorous, but perhaps amused-chuckle-humorous?

I am a bit mystified what this endeavor is meant to accomplish. Supposing it is true that (apparent) gender identity doesn’t affect chances of one’s submission getting published, what use is this data? Is the hope supposed to be that, by making this data public, Ethics will encourage more women to submit (which assumes that the explanation of the disparity in submission rates isn’t explained largely or entirely by disparities in gender rates among ethicists!)? Why think that would happen?

I admit that I’m very skeptical that this data isn’t being used in considerations of whether to accept or reject submissions, frankly. For that would be the most straightforward way in which such data could causally impact the gender ratios of accepted authors. If it is being so used, and this fact comes to be common knowledge, the reputation of Ethics will take a substantial hit.

I can’t believe a combined 28 up-votes went to IGS and sahpa’s comments. Please give this comment a thumbs-up if you just haven’t chimed in because it’s not worth spending time trying to convince trolls of what most reasonable people think, including:

A) Obviously IGS’ first Premise 1 is false. Of course we want a higher proportion of women authors in Ethics (and other journals). As Henry Richardson says, we should at least want the proportion of women publishing in Ethics to be comparable to the proportion of women working in the fields that Ethics covers; and we’re not there yet. The profession won’t, and shouldn’t, rest until we get there.

B) We like transparency. That’s reason enough to publish these data, contrary to sahpa.

C) Another reason to reject sahpa’s comment is that it’s reassuring to know that the rate at which Ethics publishes women authors is roughly on a par with submission rates. Given the n, if it weren’t roughly on a par, we’d have reason to worry that something is going wrong. Now that we know that this isn’t the problem, we can look elsewhere for the problem (as Ethics is doing).

D) The people who run journals like Ethics are doing valuable work, for which we should be thankful. It is not acceptable to level the baseless accusation that they are secretly manipulating gender ratios without telling us. We have a much better explanation of why they are collecting the data: they want to be sure they *are not* biasing the system against women, and they want everyone to know what the journal is doing. C’mon.

Regarding B: sure, we like transparency. Some of us also like our personal information to be used in data analysis only with our consent, and there is no indication that Ethics has heretofore sought that (I mean, for godssake, they would do an internet search on you if they couldn’t guess from your name–do you *really* think they were getting consent beforehand? if they were, why didn’t they just *ask* for your gender information?). Going forward, that problem looks to be going away, provided that the “N/A” answer really doesn’t affect your submission’s chances.

Next, let’s not chill my speech by accusing me of “unacceptable” behavior. Nothing I said was unacceptable. I did not defame anyone, nor did I slur anyone, nor did I even straightforwardly accuse Ethics of any misconduct–and even if I *did*, that in itself is not unacceptable! And nor was my accusation (sic) baseless: I provided the rationale in the immediately following sentence.

And here’s the bald truth: a genuine blind-review process ensures that the system is not biased against women (or any other protected group, for that matter). (Don’t start going on about implicit bias now–anyone who’s read the science on that notion knows you won’t have a leg to stand on.) Under the assumption that Ethics has a genuine blind-review process, gathering this data for the purposes you appeal to in D (as if this were *obviously* the explanation) is simply unnecessary. Which makes one wonder whether the assumption should not be loosened. Which is what I did, unacceptable though such a thought may be to someone like you.

Your accusation was baseless in the sense that there’s no basis for going with your conspiracy theory, when we have every reason to believe the editors are collecting the data for the reason they state. These are our colleagues and, for some people, friends. I think it is unacceptable to state these accusations about them there without a compelling reason.

Blind review doesn’t guarantee a lack of gender bias; it just screens for the most obvious forms of it. In any case, why care that we get confirmation that it’s working? That should be something we’d all welcome.

I’m loving the motte and bailey strategy on display here. You keep acting as though this whole procedure is just meant to verify that their publishing process doesn’t exhibit gender bias (what an unimpeachable thing to want! surely we all welcome that!) even though, in the outgoing editor-in-chief’s *own words*, the aim is much more ambitious: “to aid the cause of reducing gender imbalance in philosophy publishing”. And, wouldn’t you know it, I *do* believe that they are collecting this data for the reason they state! But I want to know *how* they plan to use the data to do that, and am worried they might do it in a bad way (or, to put the point differently, I see how some of their aims press against some of their other aims, such as the aim to preserve the blind-review process free from influence by gender considerations). But, sure, let’s start calling me a conspiracy theorist so that we can pretend I’m not actually taking their own words seriously.

Lea, presenting a logical argument and asking for a more specific justification makes me a “troll?” I have to say, I take care entering these conversations because I know how quickly they can be inflamed, and I respect that those confrontations can be very alienating. If you specifically argue where and why I was not “reasonable,” I will happily take that into account the next time–it is something that I do consider.

As to your substantive response, it does not seem intuitively unreasonable to want at least the proportion of women in Ethics to be as great as the proportion in ethics and related fields. I could be convinced of that pretty easily, but you have only repeated the conclusion here. What would convince me is a justification that gives me at least some idea how that desideratum relates to other desiderata that we have for Ethics as a journal.

Lea Per, why should we accept your own assertion (“Of course we want a higher proportion of women authors in Ethics (and other journals)”? Your attack on the previous poster is all the more ironic given how much you beg questions in your own.

I for one would like to see the journal publish the best quality articles, regardless of gender. If accepting the best quality articles means accepting a higher proportion of women authors, I am perfectly happy with that; if accepting the best quality articles means accepting a lower proportion of women authors, I am ok with that, too. This is not an indefensible position, or one that must “obviously” be false.

Please don’t try to paint everyone who doesn’t agree with your ideological and political priors as engaging in bad reasoning, or call them trolls, or try to shame them with sanctimonious commentary. The point you claim as “of course” true is far from it.

IGS, I can see now how you weren’t trolling. Please accept my apologies for throwing that label out there. I was assuming it was clear that while of course we want Ethics to publish good articles (period), we also think, for good reason, that women produce Ethics-worthy articles at a rate comparable to men. (And we now have some more evidence of that from the journal, where the sample, admittedly, is made up of those who have in recent years submitted to Ethics.) If we think that women produce Ethics-worthy articles at a rate roughly comparable to men, then having a higher (than the currently disproportionate) rate of women would be good, for all sorts of reasons. (I’m not sure what work “inherently” is doing in your first first premise, and maybe that’s where the problem is for me. It can’t mean intrinsically, right? At least, I doubt anyone would say your first first premise under that revision. So, I’m not sure what it means.)

On another note, you and GradStudent both say that I beg the question (or “only repeated the conclusion,” in your case). I’m not trying to make an argument. I’m merely lamenting the fact that apparently we still have to have a conversation about whether men and women should be roughly proportionately represented in Ethics.

Thanks Lea, I think that many would agree that in a well-ordered society under fair equal opportunity, as Rawls might describe it, men and women would be roughly proportionately represented in Ethics. (I say “many” because some could argue that there are natural or inevitable differences in the genders that would affect publication rates, but I will set that aside for the sake of this point). In this sense, we could say that these people agree that men and women should be proportionately represented as you say.

However, even if we agree with this statement, it does not necessarily follow what institutional steps should follow from this view. One position could be that gender discrimination should be addressed (only) in a systemic way, trying to build from the ground up and individual institutions should only remain “neutral” to gender, in some sense, where “neutral” means non-discriminatory here. These steps would be justified at the societal/macro level. Another position could be that *every institution* should reduce imbalanced outcomes by any reasonable means. These steps would be justified at the individual institution/micro level, but the sum effects might be unclear at the societal level. There are many hybrids of these approaches as well, of course.

Given this plurality of reasonable positions, I am concerned by the statement in Richardson’s statement: “…we obviously need to increase our efforts to encourage women philosophers to submit to this journal. We have begun to do so by making the journal more receptive to feminist work in ethics, political, and social philosophy, such as the first two articles in this issue.” This seems to allow the goal of gender balance to influence the content of the journal. If we feel very justified by the need to address gender imbalance at the institutional level, I can imagine a good argument defending this position. However, I do not see it in Richardson’s statement, and I don’t think that it necessarily follows without further justification even if we agree with the idea that men and women should be roughly proportionately represented in Ethics in an ideal world.