Why Science Education Needs Philosophy

Many of the young people who attend my classes think that philosophy is a fuzzy discipline that’s concerned only with matters of opinion, whereas science is in the business of discovering facts, delivering proofs, and disseminating objective truths. Furthermore, many of them believe that scientists can answer philosophical questions, but philosophers have no business weighing in on scientific ones.

That’s Subrena Smith, assistant professor of philosophy at the University of New Hampshire, writing at Aeon. Her essay, “Why philosophy is so important in science education“, should be circulated widely to science educators and students.

She continues:

Why do college students so often treat philosophy as wholly distinct from and subordinate to science? In my experience, four reasons stand out.

One has to do with a lack of historical awareness. College students tend to think that departmental divisions mirror sharp divisions in the world, and so they cannot appreciate that philosophy and science, as well as the purported divide between them, are dynamic human creations…

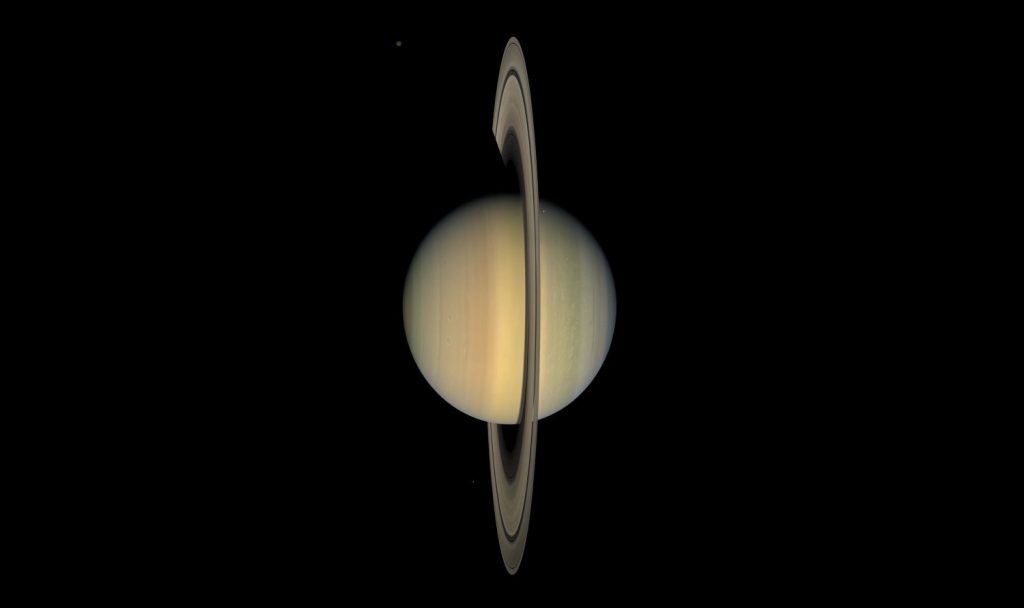

Another reason has to do with concrete results. Science solves real-world problems. It gives us technology: things that we can touch, see and use. It gives us vaccines, GMO crops, and painkillers. Philosophy doesn’t seem, to the students, to have any tangibles to show. But, to the contrary, philosophical tangibles are many: Albert Einstein’s philosophical thought experiments made Cassini possible. Aristotle’s logic is the basis for computer science, which gave us laptops and smartphones. And philosophers’ work on the mind-body problem set the stage for the emergence of neuropsychology and therefore brain-imagining technology. Philosophy has always been quietly at work in the background of science.

A third reason has to do with concerns about truth, objectivity and bias. Science, students insist, is purely objective, and anyone who challenges that view must be misguided. A person is not deemed to be objective if she approaches her research with a set of background assumptions. Instead, she’s ‘ideological’. But all of us are ‘biased’ and our biases fuel the creative work of science. This issue can be difficult to address, because a naive conception of objectivity is so ingrained in the popular image of what science is…

The fourth source of students’ discomfort comes from what they take science education to be. One gets the impression that they think of science as mainly itemising the things that exist—‘the facts’—and of science education as teaching them what these facts are. I don’t conform to these expectations. But as a philosopher, I am mainly concerned with how these facts get selected and interpreted, why some are regarded as more significant than others, the ways in which facts are infused with presuppositions, and so on.

Smith understands that various pedagogical pressures mean that there isn’t much room for doing philosophy in science courses, but our colleagues in the sciences can still help by “making clear to their students that science brims with important conceptual, interpretative, methodological and ethical issues that philosophers are uniquely situated to address.”

Read the whole essay here.

So all of the reasons are things for which philosophers conveniently can’t be held accountable?

the source of my students’ valorization of science is that scientists, as a community, come to relatively stable conclusions, and philosophers by and large do not.

You could point out that the vast majority of scientific conclusions historically have been false, and much of current science will probably also turn out to have been false.

Then a difference between science and industry could be, ‘research and development’ verses ‘research and observation…

…Examples of science and philosophy abound…

Prof. Smith’s argument seems to be this: science has better marketing. Scientists have successfully established themselves as peddlers of facts (wrong as that may appear to a philosopher), whereas philosophy has somehow ended up as the peddler of opinion (in the public eye). She is quick to attribute this ill repute of philosophy to anyone but philosophers themselves. So she laments it as undeserved and moreover asks, nay, demands, of scientists that they include us in their marketing scheme.

I think this is misguided.

My early education actually saw a high school physics teacher who was very conscious of philosophical issues. Whenever he ventured into the non-tangible realm of 20th century physics (elementary particles and whatnot), he was very careful to remind us of the epistemological and metatheoretical issues involved (e.g. why do we take this experiment to evince that). But in the end, he said, philosophers wonder—and physicists do: physicists establish the facts, and philosophers ponder them. Apparently, Prof. Smith agrees with my old teacher here:

“as a philosopher, I am mainly concerned with how these facts get selected and interpreted, why some are regarded as more significant than others, the ways in which facts are infused with presuppositions, and so on.”

So, my old teacher went on, he became a physicist: because philosophers can wonder all day long, but a physicist will still do physics—which to him is an inherently interesting activity! Philosophical issues can be bracketed since they won’t be solved anyway, but one should be aware of them.

Prof. Smith continues:

“science brims with important conceptual, interpretative, methodological and ethical issues that philosophers are uniquely situated to address”

To address—but not to answer. And isn’t that the problem?

What Prof. Smith masquerades with talk of “objectivity” and “truth” is this. Science is in the business of incrementally building up a consensus; philosophy is not. We can cry and shout as much as we want, but this fundamental difference persists—even when we question the concepts on which the scientific consensus rests and even when we force the scientists to teach these questions.

It appears as a plain fact that consensus-building is far more desirable to a majority of students.

And to my old physics teacher.

Philosophy need not be committed to denying the value of the incremental build-up of consensus, which is a very good way of describing what’s missing.

What is the nature of this consensus? How to achieve it? What is it based on? Physicists, philosophers, and others are going to want to answer these questions, to the extent they can.

The problem of induction need not be understood entirely as a skeptical problem separate from statistics. Hacking’s Introduction to Probability and Inductive Logic takes the reverse course: the problem of induction emerges from his instruction in probability and statistical method. Statistics students who are taught a collection of arbitrary recipes might wonder why this works. And if they don’t wonder, then that’s a problem, which results in a lot of abuses, some of which are social and ethical problems.

The problem of knowledge and skepticism isn’t just something thought up by a guy in a well-heated room talking to God a long time ago. Descartes was, at the same time, trying to figure out what kind of structure the universe needs to have in order for science, as he understood it, to make sense as a way of getting knowledge (and how to talk sensibly about this). Philosophers’ talk about skepticism is an abstract and efficient way of getting at this. Broughton’s interpretation of Descartes, and Maddy’s use of it and of cognitive psychology, reconnect the skeptical problem with scientific questions. No doubt there are other ways of making the link.

I’ll get off my high horse now.

Having studied the philosophy of science while in graduate school, it’s hard to believe that any non-philosophy/science student would not appreciate the deep, eye-opening significance of the various issues covered in those courses — which are typically ignored in ordinary, non-philosophy science classes.

So when we began to bury people…Was it because of what we sensed or felt or thought…..

…When did we begin to mind about other peoples bodies and our own bodies…

When did our Minds and Bodies become objects for Observation…

…Seeing Who we are, What we are–Can’t have one without the other…

Forget this (teacher-student) and history will continue to repeat itself…