Being A Woman In Philosophy: Then and Now

From an essay about, among other things, the interplay between philosophy’s history and its current practices:

Early in my academic career I had started to find the climate of academic philosophy unwelcoming to women. No one in my department taught works by women philosophers; a mentor had openly doubted women’s ability to do philosophy. As one of the few women in the program, I was lonely. I believed women could make significant contributions to philosophy, but even so, I questioned whether philosophy was a place where they could thrive.

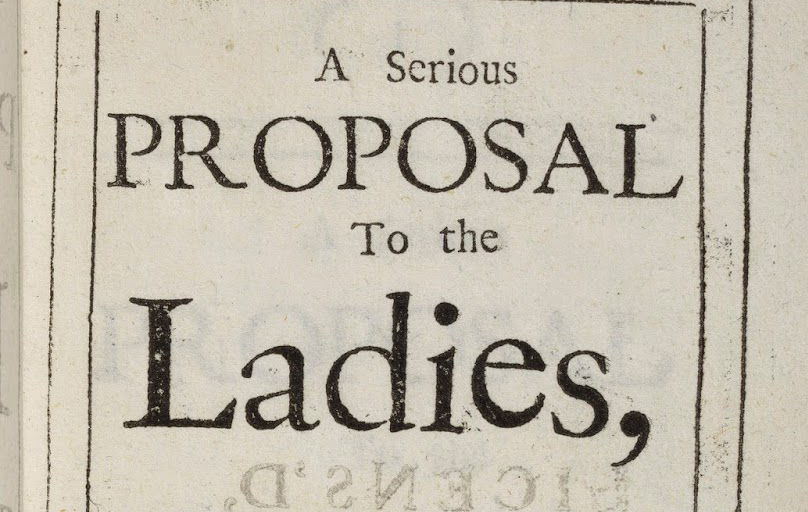

This began to change the year I arrived in Iowa. One afternoon I was reading an obscure monograph when a footnote led me to A Serious Proposal to the Ladies by Mary Astell, who lived from 1666 to 1731. I’d never read works by women philosophers who lived before the 20th century, assuming that since they didn’t show up in textbooks or in class discussions that they didn’t have anything unique or profound to say. Yet I was captivated by the title of Astell’s work. Here was a book personally addressed to women.

Reading A Serious Proposal, I was surprised to find that Astell offered complex arguments about the nature of mind and body, tackling some of the same issues of metaphysics and epistemology as René Descartes and John Locke. Yet her core message was simple: educate women so they can pursue personal happiness and contribute to society. I was amazed by Astell’s boldness and unapologetic ambition, how she willed into existence a new, heartening vision for women’s lives.

Today Astell is virtually unknown. You won’t find her ideas in most philosophy textbooks or course syllabi, and most history of philosophy scholars don’t know about her work. Anthony Kenny, who wrote the multivolume History of Western Philosophy, told me in an email that “Mary Astell is an interesting person,” although he had not read A Serious Proposal. “But can you honestly claim that her contribution to philosophy is on the same level as that of her contemporary John Locke?” he asked. Another acclaimed popular historian of philosophy told me the reason women philosophers didn’t figure in his book was his “aim was to explain the ideas of the most influential thinkers of the period—the people of whom today’s readers have heard—and none of those people were women.”

As I worked on my dissertation, I began to realize that part of the reason that philosophy lost Astell, and other brilliant women, has to do with how the history of philosophy is crafted and taught. The history of philosophy is not a comprehensive catalog of different theories, or a series of accidental events in human history. It’s an account of the development of the science of human reason as understood by a few 19th century historians, who focused on theories of knowledge. These histories of philosophy, written by men, relegated women’s concerns to the sidelines. I came to see the plight of women in philosophy in Astell’s story. And in my own.

Those are the words of Regan Penaluna, who, in the rest of her essay, “Sexism Killed My Love for Philosophy Then Mary Astell Brought It Back,” tells her story. Read the whole thing.

Comment not showing up? Check the Daily Nous Comments Policy.

I doubt if Astell’s contribution even outweights Wollstonecraft, another female thinker and early advocate for women to get educated.

Amazing.

I’m with Anthony Kenny on this one. Astell may have been good, but she’s no Descartes, Locke, Leibniz, Spinoza, etc.–neither in greatness nor influence. You can insist that editors include work from obscure women in their textbooks and anthologies, and then pretend that that work is on the same level as the early modern greats. Some will believe you because it fits squarely into their ideology, but most will see right through it. If you want to do women a favor, explain that women were not allowed the education men were in the early modern period and that this explains why there are almost no major works from them. Don’t just go hunting for texts from women in the early modern period and then, once you’ve discovered them, tell us that they’re just as good as Kant.

And then find a way to stop the path dependence in current practice.

You do realize that “etc” means “and the rest”, yeah? When you say “Descartes, Locke, Leibniz, Spinoza, etc”, who do mean? If you mean all of the philosophers of the time, then that includes Astell. If you mean all of her male contemporaries, then you are surely wrong. A class might have valuable discussions about minor figures, so why not Astell?

@P.D. Mangus: Indeed, I am familiar with “etc.” and its meaning. By “etc.” I mean all the philosophers included in Kenny’s book and similar ones that exclude discussions of, or selections from, the work of women in the EM period. “Why not Astell?” you ask. Because space in these volumes is limited. Thus, publishers employ editors, and they insist that their authors choose which figures to discuss and which to pass over. Who do you propose we boot to make room for Astell? Obviously not Hobbes, Hume, Locke, Kant, Descartes, Leibniz, Spinoza, Berkeley. Who then? Reid? Voltaire? Rousseau? Bacon? Butler? Do tell.

Maja is correct that we must take measures to stop path dependence. We certainly want to avoid giving the impression that we’ve included only men in our EM volume because men in that period were somehow intrinsically superior to women. That’s obviously false. Hence my comment about giving a historical explanation for their exclusion. But here is something that doesn’t help stop path dependence: try to convince people that the work of women in the period is as good as those men mentioned above. That’s just a lie, and anyone not in the grip of ideology can see that.

I had planned on writing a long counter-argument to Pat’s comments. As I began to sketch it out, I realized that I was basically just rehashing what I’ve learned from a number of brilliant works by contemporary women philosophers. Since men reformulating the ideas of women as their own is one of the many insidious ways that women have been written out of the history of philosophy, I won’t do that. Instead, I’ll just say that, for those interested in seeing sophisticated criticisms of almost all of these points, I suggest reading things like the following:

(1) Atherton, Margaret, ed. 1994. Women philosophers of the early modern period. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

(2) Berges, Sandrine. 2015. On the Outskirts of the Canon:

The Myth of the Lone Female Philosopher, and What to do About it. Metaphilosophy.

(3) Gordon-Roth, Jessica and Kendrick, Nancy. 2015. Including Early Modern Women Writers in Survey Courses: A Call to Action. Metaphilosophy.

(4) O’Neill, Eileen. 1998. Disappearing ink: Early modern women philosophers and their fate in history. In Philosophy in a feminist voice: Critiques and reconstructions, ed. Janet A. Kournay. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

(5) O’Neill, Eileen. 2005. Early Modern Women Philosophers and the History of Philosophy. Hypatia.

Pat’s credibility is low because s/he fails to mention Newton, Pascal, Adam Smith and Condillac in the list of ‘purported’ male greats. (Really Voltaire but no Diderot??? Butler but not Malebranche? etc.)

Anyway, any anthology that ignores Queen Elizabeth, Margaret Cavendish, Émilie du Châtelet, Sophie de Grouchy, Anne Conway, Mary Astell, and (my favorite, the hilarious) De Gournay misses out on some fantastic philosophers and also shows itself shamefully ignorant of the excellent scholarship of the last few decades and the important work that is in the pipeline.

Thanks for bringing attention to this important work! For more background on Astell see Patricia Springborg’s Broadview Edition: https://broadviewpress.com/product/a-serious-proposal-to-the-ladies/#tab-description [full disclosure: I work with Broadview]

“Springborg’s introduction clearly places Astell’s work in the context of two important early eighteenth-century crosscurrents, the ‘woman’ question and the debate over empirical rationalism. She grounds Astell’s writings in the tradition of imagining intellectual communities of and for women but Springborg also usefully sets them in the context of the larger philosophical debates over Locke’s epistemology of environmental conditioning and psychological sensationalism. Thus, Astell takes her place again among the voices of the Cambridge Platonists and the supporters of the Port Royal School in this defining debate touching education and politics, both national and domestic. The inclusion of four appendices (Drake’s “Essay in Defence of the Female Sex,” Defoe’s “An Essay upon Projects,” and two essays from the Tatler commenting on Astell) make this a splendid package.” — Margaret J.M. Ezell, Texas A & M University

Unlike Pat, I find the Kenny line a bit odd (or at least underdeveloped). Suppose Hume is a better philosopher, even a much better philosopher, than Reid. Is that a reason not to teach Reid in an Early Modern Philosophy course? Maybe I misread something, but I didn’t see Penaluna claiming that Astell was (in Pat’s paraphrase) “just as good as” this or that canonical figure. The point seems to be simply that Astell’s work is objectively good, interesting, and relevant, and that there aren’t compelling reasons for always excluding her.

Perhaps some people think that Astell’s work fails to meet some absolute, objective measure of quality or relevance, but the mere gesture at comparative judgments in rhetorical questions doesn’t show that any more than it would with the canonical philosophers themselves.

@Joshua: I think I address your worry above in my reply to P.D. Mangus.

Hi Pat – thanks for the note. You write,

“Who do you propose we boot to make room for Astell? Obviously not Hobbes, Hume, Locke, Kant, Descartes, Leibniz, Spinoza, Berkeley. Who then? Reid? Voltaire? Rousseau? Bacon? Butler? Do tell.”

You’re talking here about books like Kenny’s though the same point is often made about syllabi. Here is what I think is (again) a bit odd about this line: Don’t plenty of books and syllabi de-emphasize this or that canonical figure, for reasons of space? And then every now and again you try to get someone reviving interest even in a canonical figure’s less-influential work (e.g., Descartes’ moral philosophy).

So take a book or syllabus that overlooks, say, Bacon. Now suppose that author or teacher opts to add Astell to their book or course. Is there something wrong with this?

“Is there something wrong with this?” No. I take including Astell in one’s book/syllabus to be permissible (in some sense). I meant only to defend Kenny and others who include only men in their books/syllabus from the charge that THEY’VE done something wrong by including only men. The thought was this: If what we’re doing in EM books/courses is introducing students to the best or most influential ideas of the time, then one cannot complain that no women are included because women did not publish the best and most influential ideas of the time. This is, of course, because men were oppressing women in the EM period (as they often do now). This should always be emphasized.

I suppose I was also objecting to the idea, which one often hears, that women actually DID publish some of the best and most influential ideas of the time, but that men were then, and are now, suppressing this fact.

“Suppose Hume is a better philosopher, even a much better philosopher, than Reid.”

But why suppose something that’s obviously false? Couldn’t get past this.

Fair enough! I myself don’t accept the supposition.

By the way, I want everyone in professional philosophy to take note of the fact that I have given Pat’s reply to me a “thumbs up.” This is my way of showing that peace, love, and understanding are possible even across contentious divides.

I note here that I have also given Joshua the thumbs up in peace, love, and understanding across contentious divides.

Here are some recent works on Astell:

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-philosophy-of-mary-astell-9780198716815?cc=us&lang=en&

http://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-07124-4.html

And to follow up on ending path dependence: women haven’t been historically excluded from philosophy because philosophy *specifically* is a sexist practice. Women have been historically excluded from philosophy for the same reasons that they’ve been historically excluded from professional life in general: society in general is a sexist practice (e.g., patriarchal family relations, sex/gender roles–especially bearing/nursing/raising children, formal exclusion via laws (esp. in the past), etc.) But just because this exclusion has been/is endemic to society in general rather than to philosophy specifically doesn’t mean that philosophy specifically (as an institution) shouldn’t aim to stop itself from reproducing the patterns found in society.

“Teach only the best” is a remarkably restrictive directive and would I think have as a consequence that everyone writing philosophy today shut up immediately. Ask yourself: Am I as good as Kant? In the early modern period there were many more people writing philosophy than the handful we have canonized and much of what they write is interesting and well worth reading and thinking about. This is true of many men and many women writing at that time. I might add that many of the women were recognized by men of their time as interesting and talented philosophers. It is unfortunate that the love of ranking that prevails in philosophy today has as a consequence that a great deal of worthwhile work is dismissed as “not the best”.

What I said has no consequences for what people today should write, since my comments so far have been about which figures should be included in EM anthologies, overview books, and courses. Nor does anything I said entail that there is not lots worth reading from the EM period.

“I might add that many of the women were recognized by men of their time as interesting and talented philosophers.” This has not been denied. Nor has anyone “dismissed” the writings of those who were not the best. By all means read these texts.

The suggestion was that authors and editors who only include the best ideas from the EM period should not be castigated for failing to include women in their volumes. No love of ranking here. Just limited space in volumes.

I agree with Pat. Space in these books are finite, and wise editorial decisions need to be made. The idea is to cover the most influential philosophers of the given historical time period, most of whom are going to be men. Perhaps this is due to men being afforded better educational opportunities and other sexist reasons, but it is a fact that the best/most influential philosophy in history was written by men. Hopefully that will, and is, changing. It certainly isn’t a fact to be proud of as it was the result of systemic sexism, but one cannot change the past, and books about the history of philosophy need to reflect history.

If one wants to go and write a specialized book about the more unknown and less popular figures in the history of Western philosophy then I think that’s great and it should be done. But my only point is that we shouldn’t expect authors like Kenny, who are writing on the history of Western philosophy generally, to include the works of women just for the sake of including women, or have to bend over backwards to argue that their works are just as influential to the history of Western philosophy as Hume for instance, when space is limited.

Well, really, as others have remarked, there is no reason to suppose anyone has to make arguments of this sort, whether space is limited or not. But these notions about the obvious limitations of space that would prevent poor old Kenny from including any but the most major of philosophers are a little puzzling. Most historians of philosophy working today would not dream of producing works dealing with Western philosophy or periods therein without including a good deal of mention of other figures besides the big seven, and would certainly include discussions of relevant women doing philosophy. Somehow or other there seems to be ample space for them to do history of philosophy the way they think it ought to be practiced.

All I can say is that if The Economist can get on board promoting early modern women philosophers, like Emilie Du Chatelet, then maybe the discipline of philosophy might consider rethinking its canon. http://www.economist.com/node/6941672

I can’t figure out what you’re suggesting. Are you suggesting that academic philosophy take its cues from The Economist? Why the heck should we do that?

I have found that the best bowl of mixed nuts is rarely the bowl that includes only those nuts widely regarded as the very best nuts, nor even the bowl that includes only those nuts that I regard as the very best nuts.

Indeed! Especially if one hopes to be edified by one’s bowl of mixed nuts.

Or are sharing with some other people, not all of whom agree about what the best nuts are or what makes a nut an especially tasty contributor to a bowl of mixed nuts.

I believe that the problem here belongs to a subclass of the larger problem,”‘How should we approach *non-canonical figures* in philosophy classroom?”, so I will just concentrate on this broader term. (Of course, gender is the salient feature that has structurally prevented talented philosophers from being recognized in the canon, but I think this feature can be abstracted away for the sake of argument since it will be applicable mutatis mutandis to other factors as well, e.g., culture, ethnicity, etc.)

From the perspective of one who does not really intend to teach history of philosophy per se in philosophy 101, I find myself ambivalent about deliberately introducing ‘non-canonical’ figures in the class.

As it is widely agreed, I believe that introducing the work by philosophers currently marginalized in the canon should encourage students that our profession has largely paid little attention to. For that reason, if I find a canonical figure X and a non-canonical figure Y independently expressing more-or-less the same idea, I will opt for teaching Y instead of X in many occasions. (e.g., I didn’t have an actual chance yet, but I have been thinking of teaching one-over-many argument for abstract object not with reference to Plato but in the form introduced by neo-Confucian moral metaphysicians). For in either way students will get to learn a philosophical device that will be useful for discussing contemporary topics.

But I am not so sure if we should introduce non-canonical figures solely for the sake of ‘revisiting the forsaken’, insofar as we do not want to devote phil 101 course to the history of idea. It is evident our textbooks are missing the names of numerous important philosophers despite their philosophical sophistication as well as their actual contribution to the history, but I don’t think it necessitates amending the textbook to include them if the addition does not thereby significantly widen the conceptual inventory of a student. As others pointed out, we have limited time and space, so it would be better to focus on those that make difference in the present.

For these reasons, I am all for highlighting non-canonical figures in curricula for instrumental reasons, but I am unsure whether there are more rationales available.

I think it’s probably the case that we are covering the people who we take to still be influential in our own time, not people who were influential in their own time. (That is, I suspect that that there are many people who were influential in their own time, but who have been since forgotten and don’t get taught, and there’d be similar controversy about bringing them into the canon). And if that’s right, then saying that we don’t teach someone because they’re not “influential” is self-reinforcing. Who is influential in our time is strongly affected by who is taught. And so, we need to think carefully about what we want our students to be learning. We cannot just default to “influence” as though it is immutable.

From the OP:

Early in my academic career I had started to find the climate of academic philosophy unwelcoming to women. No one in my department taught works by women philosophers; a mentor had openly doubted women’s ability to do philosophy.

= = =

This was not my experience at all. I wonder how representative it is.

Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Iris Murdoch, Ruth Barcan Marcus, Mary Midgely, and Mary Mothersill were all prominent parts of my education and were highly regarded by my professors, men and women alike. And they are just the ones that I got off the top of my head.

“I wonder how representative it is.”

Probably not very. It was likely said for dramatic effect in trying to over exaggerate her point.

Ruth Millikan, Judith Jarvis Thompson, Cora Diamond and of course, given my moniker, Simone de Beauvoir, are also important thinkers I engaged with in my undergrad years.

You left out Judy Thomson

Yes, of course. Though, interestingly enough, I think I first encountered her work in graduate school. Cora Diamond also. But the one’s I listed I read as an undergraduate, and in the case of Murdoch, of course, there were also the fantastic novels virtually all of which I read through college.

The only woman phpilosopher I was assigned to read when I was an undergraduate (Oxford 1976-1980) was Margaret Wilson on Locke. I still remember my disappointment on learning that Hilary Putnam was a man!

That’s interesting. I’m not that far after you (Michigan 1986-1990), and there were plenty of women philosophers on my undergraduate curriculum.

Well, things in my corner of Oxford, at least, were a lot better by 1983. We were prescribed Anscombe (lots of it, incl. both *Intention* and *IWT*), Foot, Marcus, N. Cartwright, as well as M.D. Wilson. Tony Kenny (who was Master of my college) held up Anscombe as the preeminent British philosopher of her generation — which we understood to mean that she was (even) better than the local profs, Strawson, Dummett, and Hare.

Daniel and Ian–I am not sure what your reports of your experience is supposed to be saying to Regan Petaluma. Is it your contention that your experience shows that hers is an anomaly? I’m not sure that you are taking on board the entirety of what she is talking about. Were there many women in your graduate program? Did you have many women as professors?

Familiarity with a handful of women–generally regarded as pioneers–is really not quite the same as taking on board the loneliness that Petaluma reports and which many women have also discussed, or the importance of the recognition that there have been women doing philosophy throughout its history.

I would have thought my comment was quite straightforward. The OP said:

“No one in my department taught works by women philosophers; a mentor had openly doubted women’s ability to do philosophy.”

And I wondered how representative that experience is for students. In my case, I was assigned many works by women philosophers, both as an undergraduate and a graduate, and it was quite clear that the faculty held them in very high regard.

That’s it. And it seems perfectly relevant, given the part of the OP on which I was commenting.

Don’t make rhetorical statements, then pretend you meant them literally

Also, I don’t see why I need to “take on board the entirety of what she’s talking about.” I was speaking to a very specific part of the OP.

I confess to having a more basic question. I’m just not seeing what the connection between “there were few women philosophers taught in my program” and “the climate of my program/discipline is unwelcoming to women”. Perhaps I am not understanding what “unwelcoming” means in this context, but typically I think of that as an interpersonal attitude (a person is unwelcoming to another person). What does it mean for a *climate* to be unwelcoming?

But even if I try to get past that basic failure to understand, I’m just not seeing the connection. Why should the fact that philosophy done by Xs isn’t taught in a program bear (in the direct, evidential way that the author offers it) on how welcoming philosophy is to people who are X?

I get that being a relatively lone X in a department can be lonely and despiriting and at times alienating. I do. I am one such person. But I’ve never made the inference that I was or am *unwelcome* in the department. I’m just a bit of an odd bug and people don’t know how to relate to me or are coming with a set of presumptions that don’t apply in my case. But it seems like I’d be projecting my insecurities onto them if I were to then conclude that they were somehow rejecting me as a philosopher.

I think what I’m resisting is the moralization of such (unfortunate and painful) personal circumstances. Talk about “unwelcome” sounds distinctly (bourgeois) moral to my ear.

I belong to neither the group of people who are underrepresented nor to the group of people who feel unwelcome in philosophy, but I have consistently heard from those who are in both groups how the two facts you mention interact. It can either be fairly direct, in that people feel like they aren’t the *type* of person who succeeds in philosophy because there aren’t many like them who are presented as philosophers (perhaps this is even implicit), or indirect in that because there aren’t many like them, it leads to comments or attitudes from others that indicate that they are an abnormality in the profession, or intellectually inferior, etc.. Of course, ideally, the fact that particular groups of individuals aren’t represented in philosophy shouldn’t have any effect on how welcome people feel.

Thanks for the detailed response. Let me try to understand better.

You suggested that people “feel like they aren’t the *type* of person who succeeds in philosophy because there aren’t many like them who are presented as philosophers”. This is kind of what I was asking about–what licenses the inference that you seem to be marking with “because”? For some type T of person, suppose there aren’t many of them in philosophy; why should that, in itself, license the inference that Ts don’t succeed in philosophy (in particular, that Ts don’t succeed *in virtue of* being Ts–which is what concerns of sexism are truly about, I take it)? I’ll allow that many people *make* such an inference. I’m question whether it is a good inference to make, because I’m questioning whether the observed thing really is evidence for the inferred thing.

In the “indirect” case, I agree that demeaning comments about someone *as a T* can make them feel unwelcome as a T. So, e.g., the OPs original anecdote about a professor openly questioning women’s ability to do philosophy. Definitely, no argument from me. But that is a different point from the representation of Ts in philosophy, and I was asking specifically about the evidential relevance (to climate questions) of rareness of Ts in philosophy. You might have the theory that such rareness leads to demeaning and unwelcoming comments, but no evidence for such a theory has been provided. In the absence of that evidence, the “indirect” connection you point to, it seems to me, is unsubstantiated. Now, you might just think it’s obvious–there will be more demeaning comments toward Ts in philosophy, ceteris paribus, when Ts are less represented in the field–but I don’t see how that’s obvious. There is no non-question-begging a priori reason to think that non-Ts can’t police what they themselves say about Ts, or that non-Ts (in conjunction with the relatively few Ts) can’t. You need evidence.

(Mixed into all this is the confounding fact that what we seem to be interested in is whether these problems are particularly acute *in philosophy*, or if the problems in philosophy might not just be reflections of broader social problems. But I don’t know exactly how to think about that.)

I read the essay and found this excerpted remark noteworthy: “As I worked on my dissertation, I began to realize that part of the reason that philosophy lost Astell, and other brilliant women, has to do with how the history of philosophy is crafted and taught.”

I think that philosophy also “loses” valuable contributions because of the ways that the history of philosophy, as traditionally taught, gets *criticized and renovated.* Why do discussions about the presence/absence of women in the history of philosophy and “being a woman in philosophy” more generally (almost) always and (very) quickly become reduced to disputes about and between nondisabled white philosophers, women and men?

For my own part, I think that the history of (Western) philosophy and of historical figures in it and excluded from it should be taught genealogically, that is, should trace the lines of what Foucault called “the history of the present.” In this way, we could, for example, consider how, and the extent to which, Locke’s remarks about “idiots” inform current discussions in philosophy of mind, cognitive science, ethics, bioethics, and so on.

Need to distinguish 2 things: 1) Whether Locke is better than Astell; and 2) Whether the philosophical framework in which Locke is given more focus than Astell is more rewarding/interesting/productive than a framework in which Locke and Astell are treated as equals or Astell as better.

Re 1: there is no fact of that matter. This is an obvious truth and doesn’t require feminism or anti-colonialism or post-modernism to justify it. There is no pantheon writ into the universe. Talk of influence or who has been considered the best or who had the most influence is circular. The world isn’t determined by actions of Olympian Gods, and philosophy isn’t an eternal battle between some set Olympian figures. There are no philosophy Gods or Immortals, only our thinking makes it appear so.

The relevant, and open, question concerns 2. Any framework ( a set of questions, topics, methods, concerns) prioritizes some figures over others. In one framework we are all very familar with Locke is given much more prioirity than Astell. Penaluna is suggesting a different framework in which Astell is given much greater priority, and clearly this framework is one which motivates her to do philosophy.

We should evaluate, critically juxtapose these two frameworks, and duke it out in philosophical argument. But neither side should cheat. If one says the Astell-priority framework is better or equally good because men and women are equally good, that’s absurd (not attributing this error to Penaluna). Likewise, if one says the Locke-prioirty framework is better because Locke is so much greater as an individual thinker, that too is absurd; even assuming Locke is a greater thinker than Astell, the greater thinker can be part of the out-dated framework.

It seems peculiar to say there is no fact of the matter regarding whether Locke or Astell was a better philosopher. It certainly isn’t an obvious truth. Saying there are ‘no philosophy Gods or Immortals’ is very different from acknowledging that historically there have been some extraordinary philosophers, of which Locke was one.

I meant: there is no fact of the matter independent of the frameworks through which we think of the philosophers. The greatness of a philosopher isn’t like who can run the fastest, but is always framework dependent. Hence if we are comparing the traditional Locke-proiority framework with the new Astell-priority framework, we can’t say the former is the better framework becuse Locke is the much better philosopher. That presupposes we can evaluate Locke’s greatness independent of the framework, and that seems false. In part because the greatness of a philosopher is usually tied to their articulating well the contours of the framework in which they are themselves exemplars.

Is Marcus Aurelius a better philosopher than David Lewis? Given the vastly different ways they did philosophy (the different frameworks they were a part of), this question boils down to comparing their frameworks of philosophy (say, philosophy as way of life and as metaphysics). Independent of comparing the frameworks, hard to get a grip on comparing just the philosophers as such.

You’re suggesting a rather extreme relativism about philosophical ability, one that I just don’t think is right. Perhaps there are difficulties comparing David Lewis and Marcus Aurelius, precisely because philosophy meant different things to each of them. But I don’t see why there shouldn’t be a truth of the matter about whether Astell or Locke was better (leaving open the possibility that Astell was actually better than Locke or, obviously, that we should study her even if she wasn’t).

I am not a relativist. I think Locke is better than Berkeley, and than Ayer, and we can debate this. This is because there is a broad framework that these philosophers had in common. When it comes to Locke and Astell, that seems to be an open question. Just because Astell was in the same time period as Locke and worked on some of the same issues doesn’t mean that the framework that applies to Locke applies to Astell. I am not an expert in either philosopher, so I make no claims one way or another. And experts, like Kenny and Penaluna, might have different takes on this.

Are Locke and Astell analogous to Quine and Ruth Barcan Marcus (clearly share a framework), or to Quine and Martha Nussbaum (less so, but still a lot), or to Quine and Judith Butler (not obvious how much they share)? Without clarifying this, comparing Locke and Astell is just a parlor game.

It might interest readers here that George Berkeley edited a 3 volume work, the ‘Ladies Library’, where the sections from Mary Astell’s ‘Serious proposal’ are perhaps the philosophically most important. It also includes extracts from Damaris Masham’s ‘Occasional thoughts’ together with familiar work on education by Locke and Fenelon.

Nancy Kendrick has a great recent paper on this.

The point about the absurdity of the idea that Locke is a better philosopher than Astell is that this belief is highly contingent upon implicit beliefs held by those who unconsciously or knowingly oppress women.

Oppressing women or others can happen by exclusionary practices in disciplines like philosophy, in higher education, and elsewhere. This can materialize in for example, a syllabus that contains only male thinkers.

To say that it is a fact that the traditional canon of philosophers are greater than many of their contemporaries that were women in the period reinforces oppressive ideals about whose philosophy is worth learning about.

One could wonder if there is any reason behind why it is that they believe that Locke and others are better than the women philosophers living during their time. Part of that reason may lie in sexist ideals that one holds that knowingly or not, silence the voices of women writers and philosophers.

If one believes in equality among persons, this entails a responsibility to inclusive practices. Those would involve including voices of women philosophers and judging their philosophy on its merits.

Reposting from a comment on an earlier thread that was posted mistakenly as a reply.

Is Astell as good as Kant? I don’t know. What unbiased perspective would I take to make that call all on my own without a community of scholars to vet it? Would I rather risk excluding someone as good as Kant from my canon or not? Pretty sure not. Let’s change the topic for a moment. How about this bit of poetry? Is it as good as the Epic of Gilgamesh? Homer? Shakespeare?

In the first days, in the very first days,

In the first nights, in the very first nights,

In the first years, in the very first years,

In the first days when everything needed was brought into being,

In the first days when everything needed was properly nourished,

When bread was baked in the shrines of the land,

And bread was tasted in the homes of the land,

When heaven had moved away from earth,

And earth had separated from heaven,

And the name of man was fixed;

When the Sky God, An, had carried off the heavens,

And the Air God, Enlil, had carried off the earth,

When the Queen of the Great Below, Ereshkigal, was given

the underworld for her domain,

He set sail; the Father set sail,

Enki, the God of Wisdom, set sail for the underworld.

Seems pretty good to me. It was written by Enheduanna, a female priestess in Mesopotamia, a full 700 years before the Epic of Gilgamesh was written down. Is this reported in all of the history books? No. Am I glad I read it? Hell yes. A simple anecdotal example, but one that tells me something, at least. I would rather seek out new sources on the off chance that we actually get greater knowledge in the end, than stay stagnant with the current level we have, as good as it might be (itself not clear). It’s also not obvious how it follows that we must give up information in order to be inclusive of equally good sources of information. Sounds pretty much like standard is conservatism to me. But as I said previously, I don’t know my Astell from my Kant. So who am I to judge?

Tired wrote:

Don’t make rhetorical statements, then pretend you meant them literally

= = =

Don’t mind-read your interlocutors. I wasn’t making a rhetorical statement.